In the District of Columbia, where housing is prohibitively expensive and neighborhoods are economically segregated, rental housing—with its lower costs, variety of units, and a more egalitarian distribution across the city’s eight wards and many neighborhoods—offers one avenue for reducing housing burdens and mixing incomes to create affordable and inclusive neighborhoods.

Rental housing’s potential capacity to create affordability and economic inclusion—and how the city can leverage this capacity—are the topics of this study. This report’s primary goal is to understand how different segments of the rental market—including the rent-controlled stock and shadow rental units—contribute to the affordability of housing and economic inclusion across neighborhoods in the District. Its secondary goal is to examine ways in which the District can leverage its rental housing to create affordability and economic inclusion, especially in parts of the city where existing public programs have not been able to create affordable housing.

Rental housing in the District of Columbia extends well beyond rental apartment buildings.

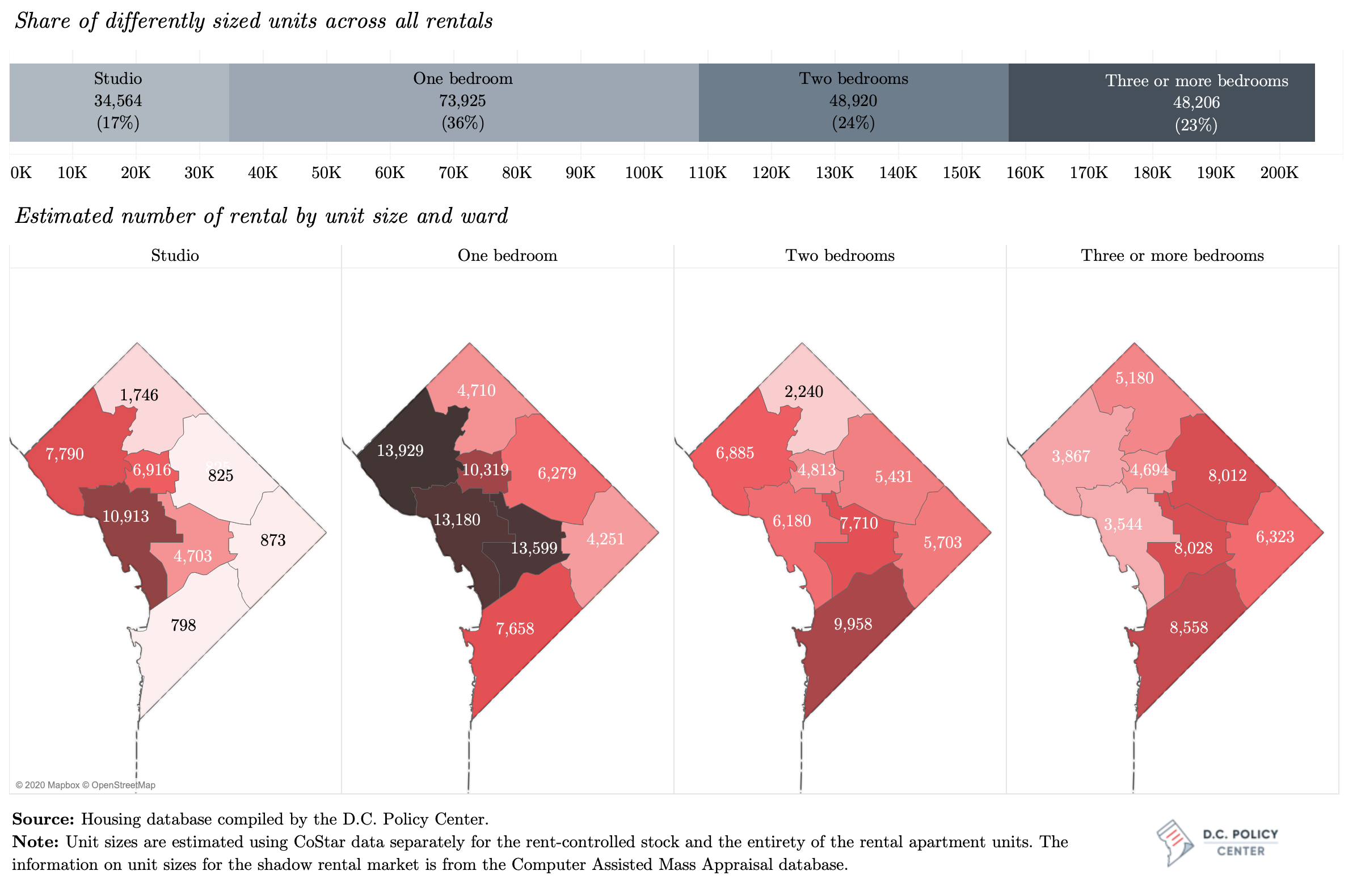

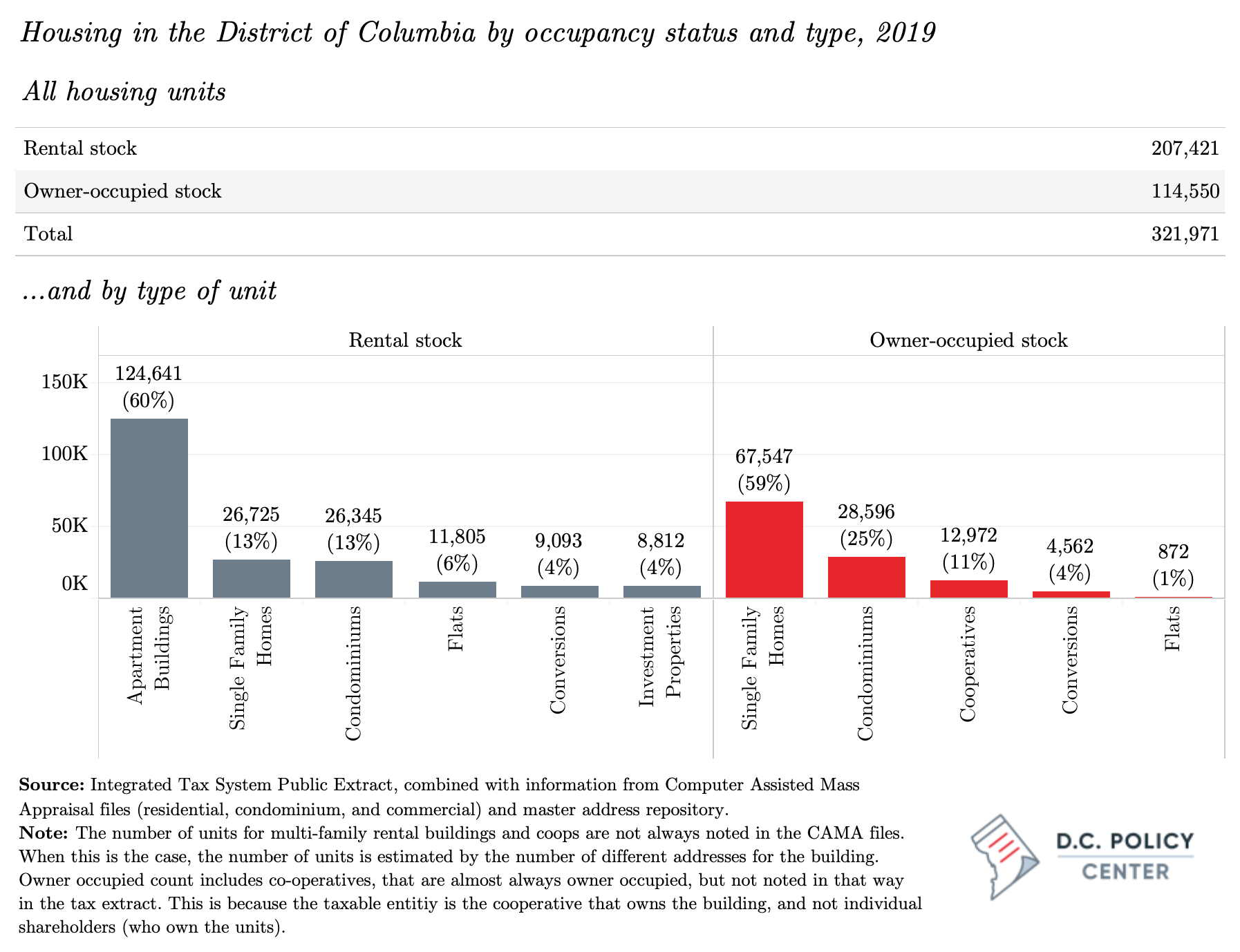

An estimated 64 percent of the District’s 322,000 housing units are rentals; of these only 124,600 are in rental apartment buildings, as classified by the city’s tax administrators. Single-family homes, condominiums, flats, and units in conversions, make up one third of the District’s rental housing. The report refers to this section of rental housing the “shadow rental market” because it is a less regulated—and sometimes unregulated—source of housing.

Rental housing is fluid.

Homeowners frequently move their units in and out of the rental market. One fifth of the 87,000 owner-occupied condominiums and single-family homes in 2006 had become rentals in 2019. Conversely, of the 39,500 condominiums and single-family homes that were rentals in 2006, nearly 15,000 (38 percent) were, as of September 2019, owner-occupied.

While rental apartment buildings are the most stable portion of the city’s rental housing, they are not entirely resistant to change, either. Some may be demolished to make room for new development, and others leave the rental stock because they are converted into condominiums or into a cooperative building.

It is difficult to track conversions through administrative data when rental apartments are converted to condominiums, but one study estimates that between 2000 and 2007, 1,147 rental apartment buildings with 26,645 units were converted into condominiums.[1] Some of these buildings were purchased by their existing tenants through the District’s Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) program. But in others, where tenants did not exercise their TOPA rights, or have signed away those rights, the units have been redeveloped into expensive units with prices the former tenants would not have been able to afford.

Rental housing is everywhere.

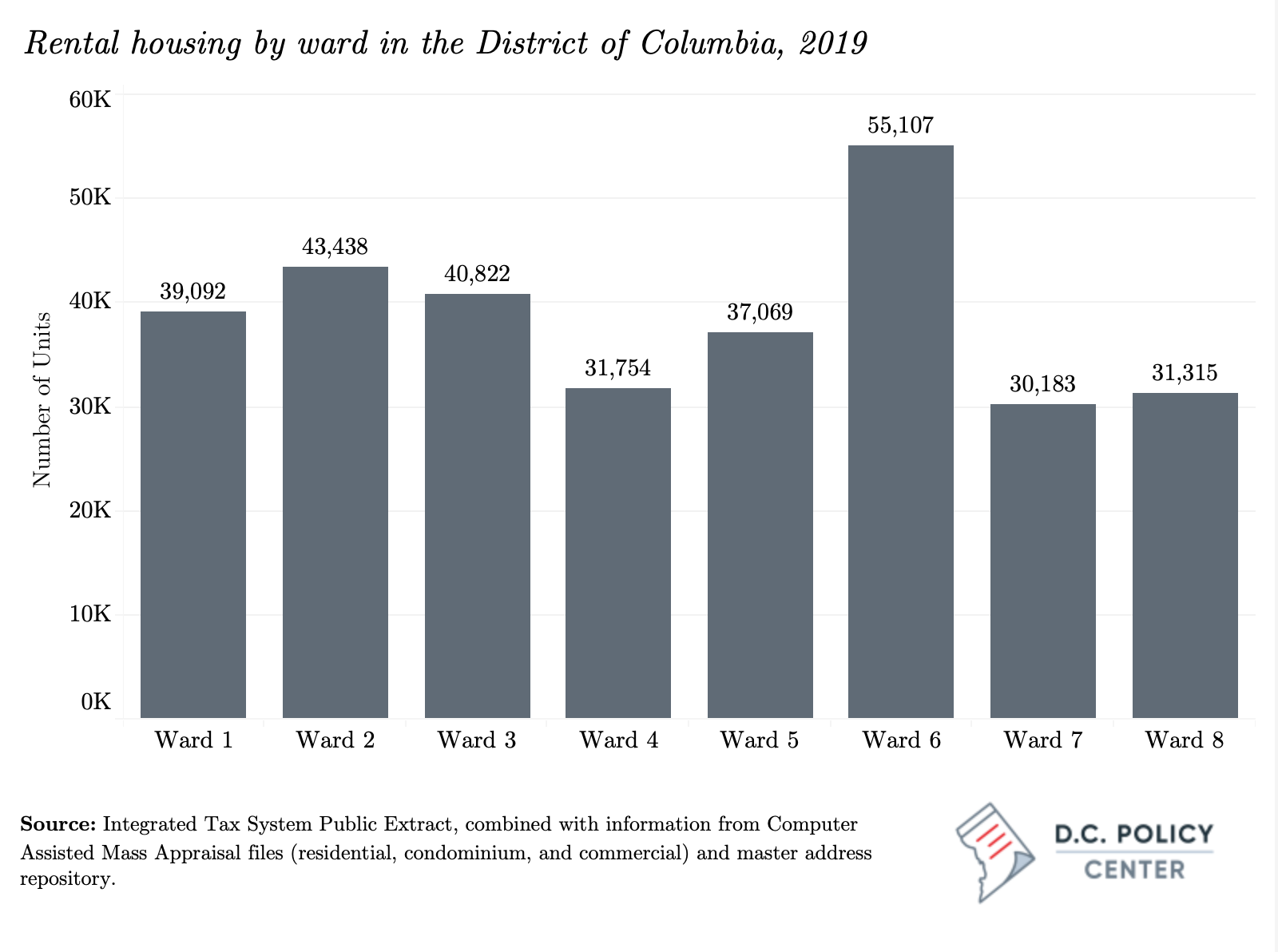

In every ward of the District of Columbia, at least 45 percent of housing units are rentals. Ward 6 has the greatest number of rentals (69 percent of all housing in this ward)—most in entirely new or redeveloped residential neighborhoods such as NoMa, Navy Yard, and most recently, the Wharf at the Southwest Waterfront. Ward 4 has the fewest rental units, as it both has a smaller stock of housing to begin with and high home ownership rates (55 percent of the homes are owner-occupied, compared to the citywide average of 36 percent). Ward 8 also stands out, as 81 percent of its housing units are rentals (only 6,000 housing units in Ward 8 are occupied by their owners).

Rental housing has been shaped by the city’s history.

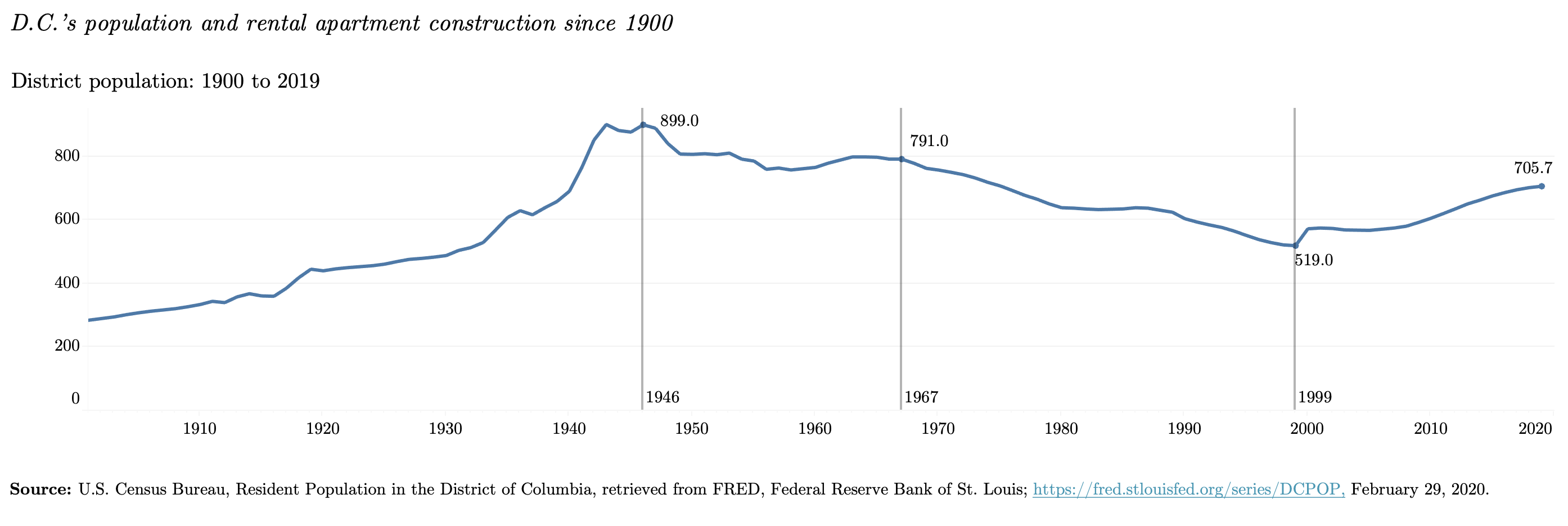

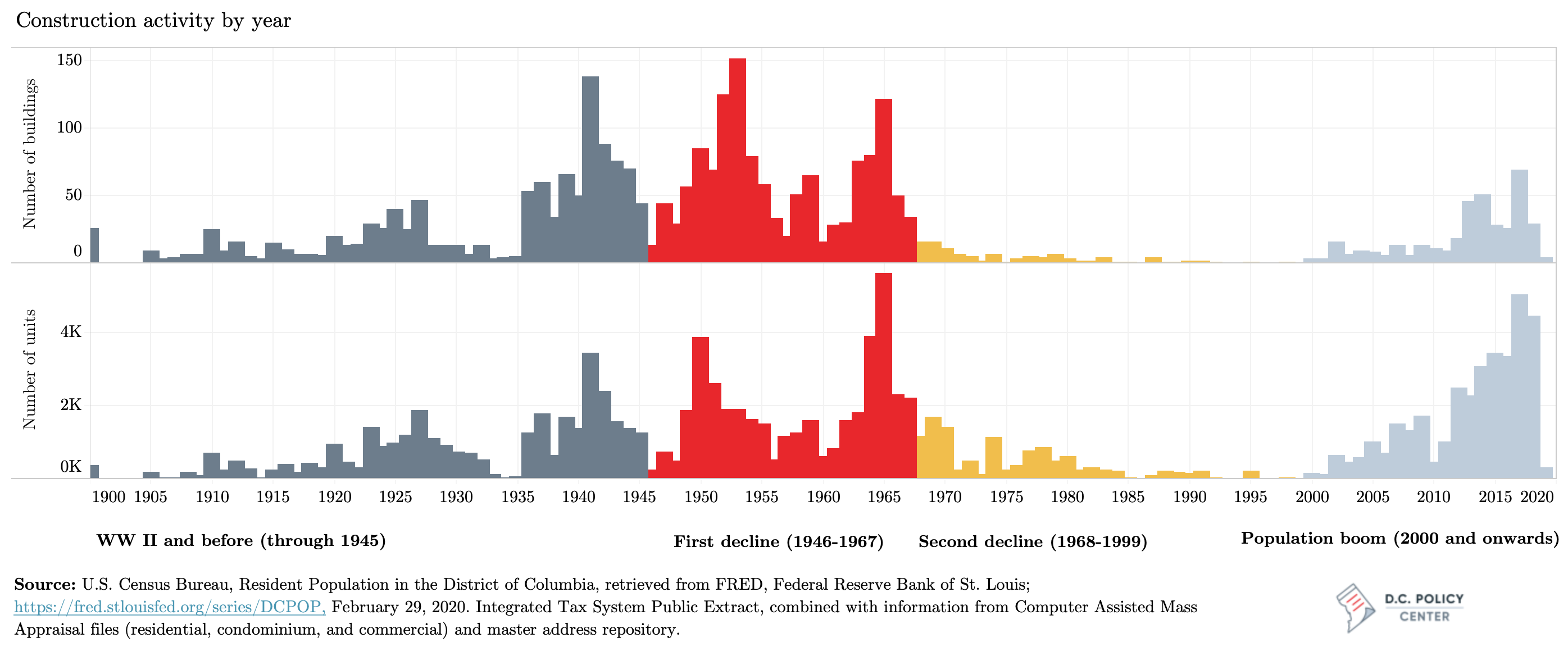

The District’s 124,641 apartments, spread across 3,121 buildings, show dramatic variety in size, location, and the configuration of unit sizes, reflecting the market conditions and zoning regulations of where and when they were built. It is useful to think of the city’s housing history alongside its changes in population, as population is a strong predictor of housing demand. In this context, the four distinct periods in the District’s population history produce four distinct periods of its rental housing production history.

One third of the rental apartments and 40 percent the rental apartment buildings that serve D.C. residents today were constructed before 1946, during a period of continuous population increase that began before the turn of the 20th century and lasted through the end of World War II. These older, smaller buildings are the source of half of the current rent-controlled units in apartment buildings.

Construction activity was still strong between 1946 and 1965, as the city’s population stabilized after its 1946 peak. However, it came to a virtual stand-still following the period of population loss that began in 1967 and continued through 1999; only about 6,000 rental apartment units that serve the residents today were built during that period.

The District’s population began rebounding in 2000, and since then D.C. has experienced one of its strongest periods of rental apartment production, despite even the effects of the Great Recession. During the past 20 years, the city has added 375 new apartment buildings (12 percent of all rental buildings in the District) with 34,000 units (almost one quarter of all units).

This combination of new and old construction in the District gives the city’s rental apartment buildings a diverse profile. More than two thirds of all apartment buildings are low-rise buildings of two or three levels without elevators, and have, on average, 20 units. Today, these buildings—typically built before 1965—dominate the landscape in neighborhoods east of the Anacostia River. In contrast, nine out of ten of the city’s apartment buildings with elevators are in neighborhoods west of the Anacostia River. These buildings are relatively new and have an average 104 units each—roughly five times the number of units that are in the city’s low-rise buildings.

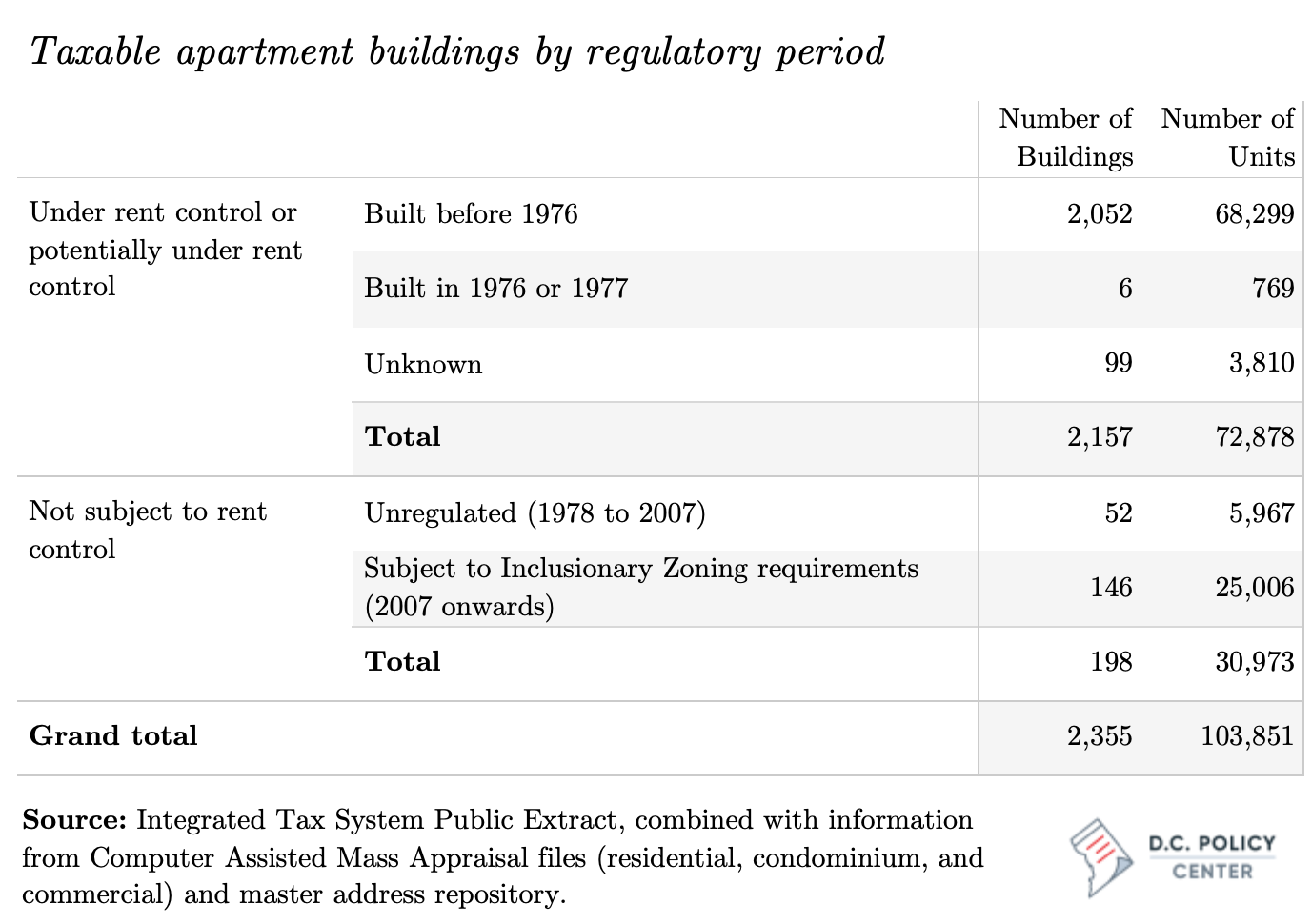

An estimated 72,900 rental apartments are in buildings under rent control.

Rent-controlled units account for 57 percent of all units in rental apartment buildings (excluding those owned by the D.C. government or managed by nonprofits, and including those not subject to rent control), 35 percent of all units that are currently being rented (including in the shadow rental market), and 23 percent of the total housing stock.

The District’s rent-controlled housing is resilient. The city has experienced some loss of rent-controlled units since the enactment of the Rental Housing Act of 1985. While it is hard to provide a precise estimate, different approaches suggest that this drainage out of the rent-controlled stock could be somewhere between 15 and 30 percent—a relatively small share compared to other jurisdictions with rent control ordinances. For example, only 10 years after San Francisco extended its rent control laws to buildings with fewer than five units, the number of rental units in such buildings had declined by 15 percent, and the number of tenants in these buildings had declined by 25 percent—a much swifter decline than what D.C. has seen. Similar magnitudes of unit loss have been documented for New York and New Jersey municipalities with rent control ordinances.

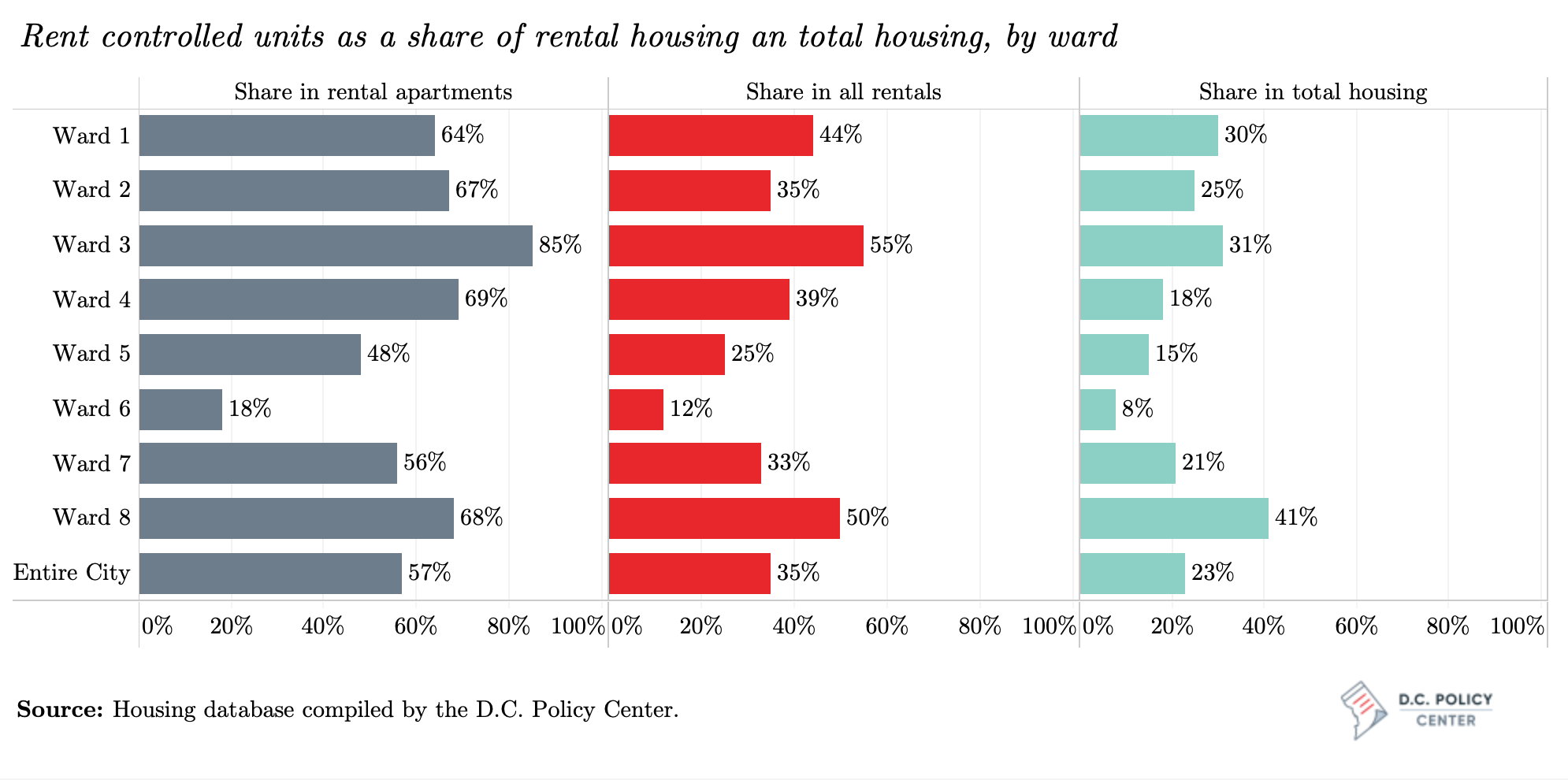

In every ward except for Ward 6, the rent-controlled stock constitutes at least half of rental apartment units.

Ward 6 not only holds the greatest number of rental apartment units in the city, but it holds the fewest number of rent-controlled units. This is because the development of multi-family buildings in Ward 6 happened almost entirely after 2000. The estimated 4,606 rent-controlled units in Ward 6 make up 18 percent of all rental apartments, 12 percent of all rental stock, and 8 percent of the total housing stock in the ward.

Rent-controlled units comprise the largest share of rental units in Ward 3 (85 percent of all rental apartments, and 55 percent of all rental housing), but the highest share of all housing in Ward 8 (41 percent of all housing in Ward 8 are rent-controlled apartments).

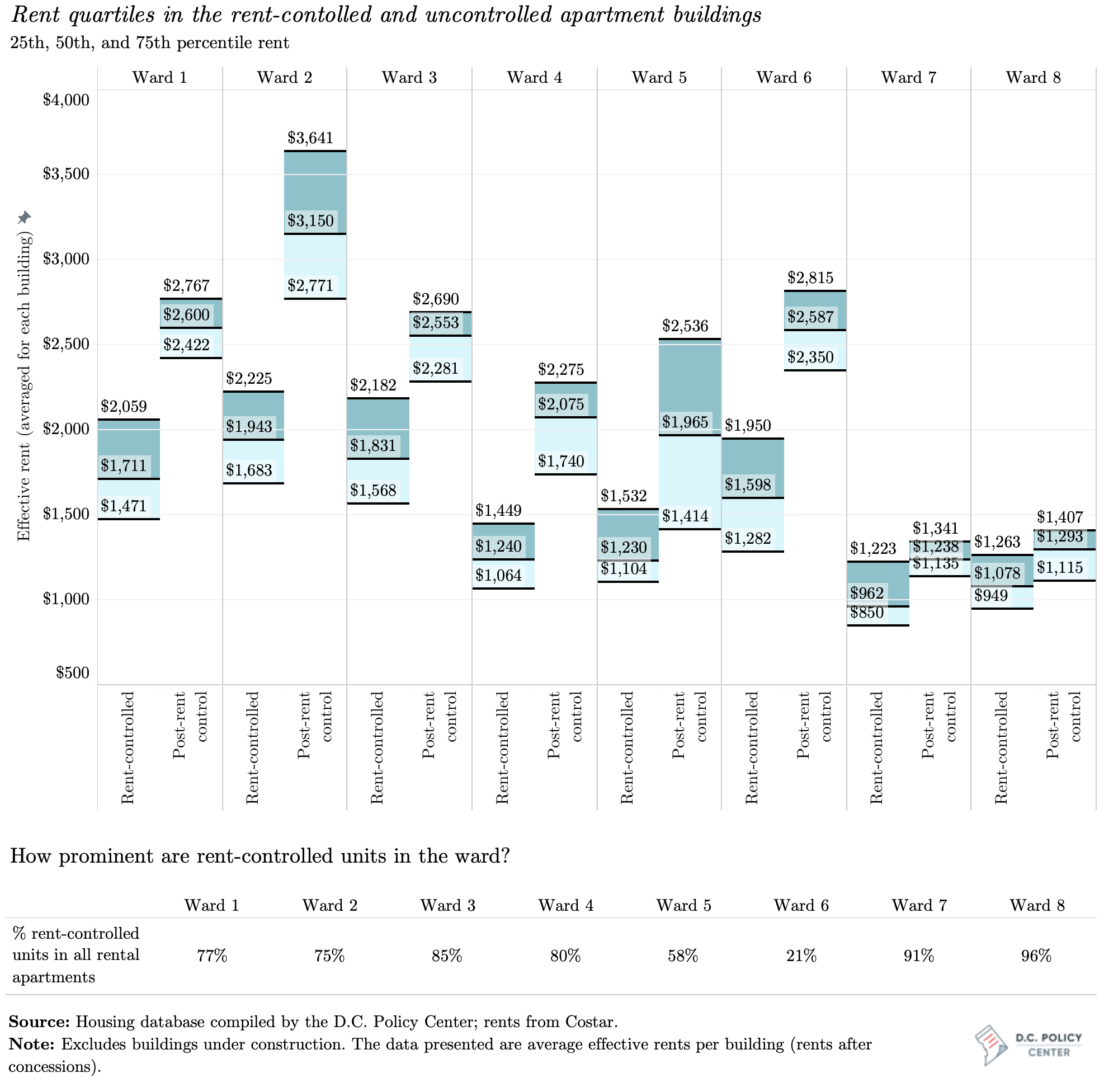

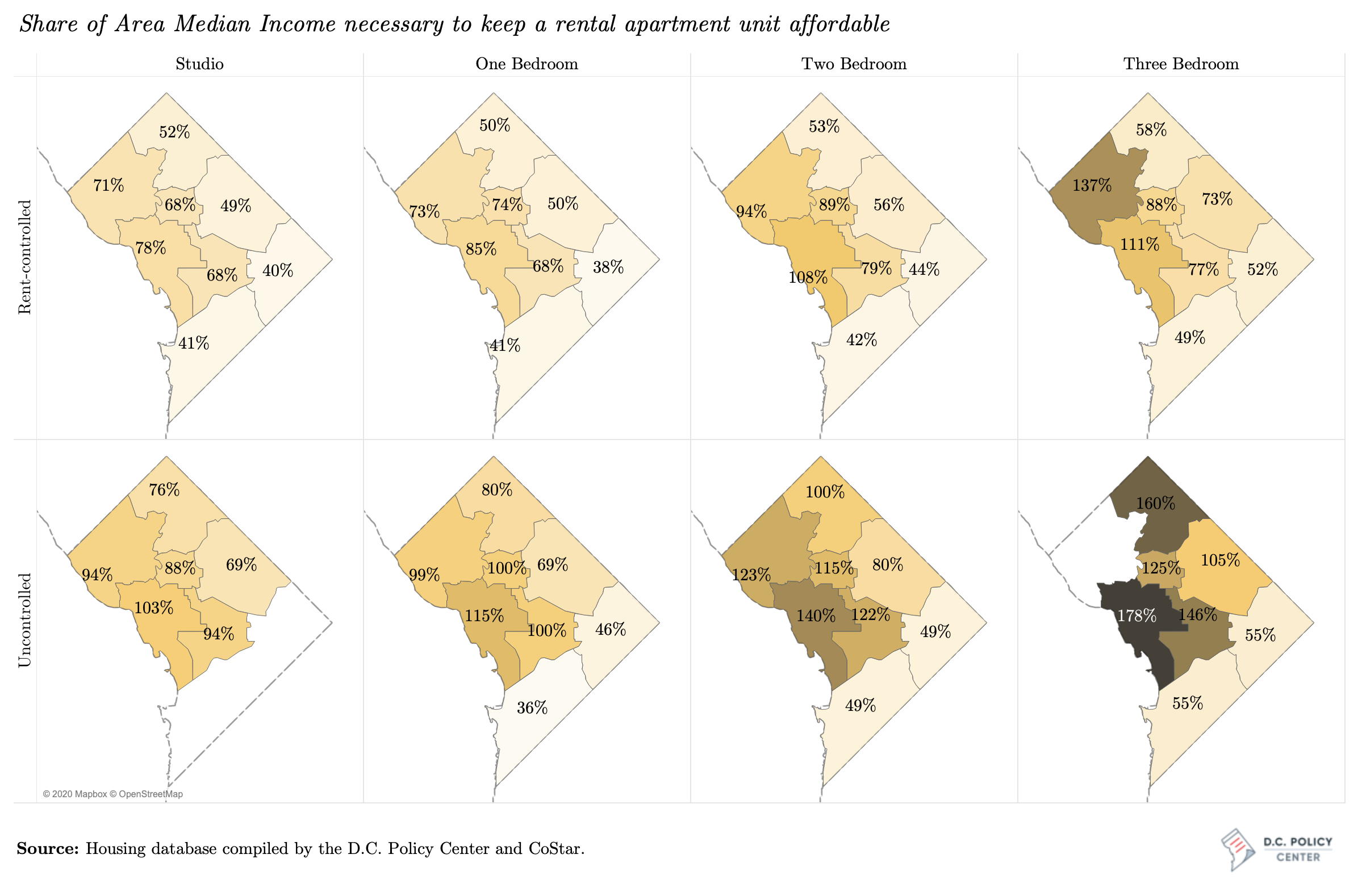

Rents vary greatly across the city and across rent-controlled and uncontrolled apartment units.

Rents increase moving from east to west in the city. Rent-controlled units typically have much lower rents than similarly sized uncontrolled rentals, especially in parts of the city where housing values have increased rapidly.

The rent differentials across rent-controlled and uncontrolled units translate into stark income differentials when examined through the lens of affordability and rent burdens. Across all wards in the District, the median rent for a rent-controlled studio apartment would not burden the renter (meaning rent expenditure is at 30 percent of household income), and therefore be affordable, at about 80 percent of Area Median Income. That is, an annual income of $67,950 for single-person household. The same person must earn $87,500—or nearly $20,000 more—to be able to afford a studio apartment from the uncontrolled stock in Ward. A two-person household with an income of $71,800 can afford a one-bedroom rent-controlled unit in Ward 1, but their income needs to rise by $25,000 to afford an uncontrolled unit in the same ward. The similar income differential that would render an uncontrolled one-bedroom equally affordable as a rent-controlled one is $31,000 in Ward 6, but only $7,700 in Ward 7.

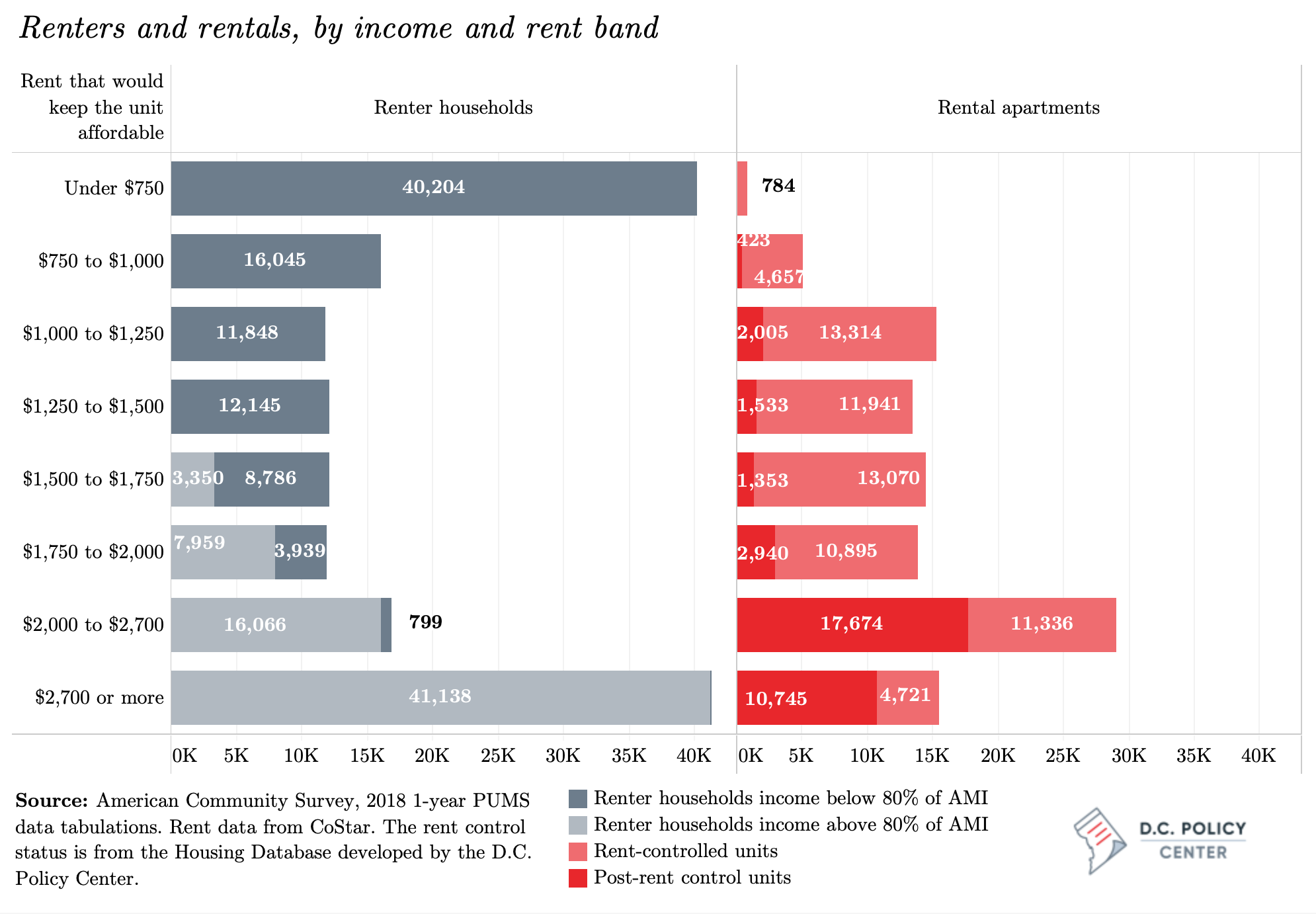

Rental apartments face pressure from renters both at the bottom and the top of the income distribution.

Of the District of Columbia’s 93,000 households that earn less than 80 percent of Area Median Income, approximately 40,000 can keep rent burdens under 30 percent of their incomes only if they spend less than $750 per month on rent. In comparison, we counted fewer than 800 rental apartment units with a rent below $750. As a result, these renters must seek housing in more expensive units (and likely seek subsidies). This pressure from the bottom is intensified by the 17,000 households that earn between $30,000 and $40,000 per year, and therefore should be paying a rent of $750 to $1,000 per month to keep their rents affordable, when the city’s rental apartment buildings can provide only 5,000 rental units that charge this rent—most of which are one-bedroom apartments.

Competing with the 40,200 renter households who must keep their monthly rents under $750 are the 41,100 households that conceivably can spend over $2,700 per month on rent and still not be rent-burdened. For this group, the District’s rental apartment buildings offer fewer than 15,500 units with rents over $2,700 per month (including 4,700 units under rent control). With their higher incomes, these households could drive rents up for units that are not under rent control. And for the rent-controlled units where rents cannot be bid up, the higher-income renter households simply compete on the same terms as lower-income households.

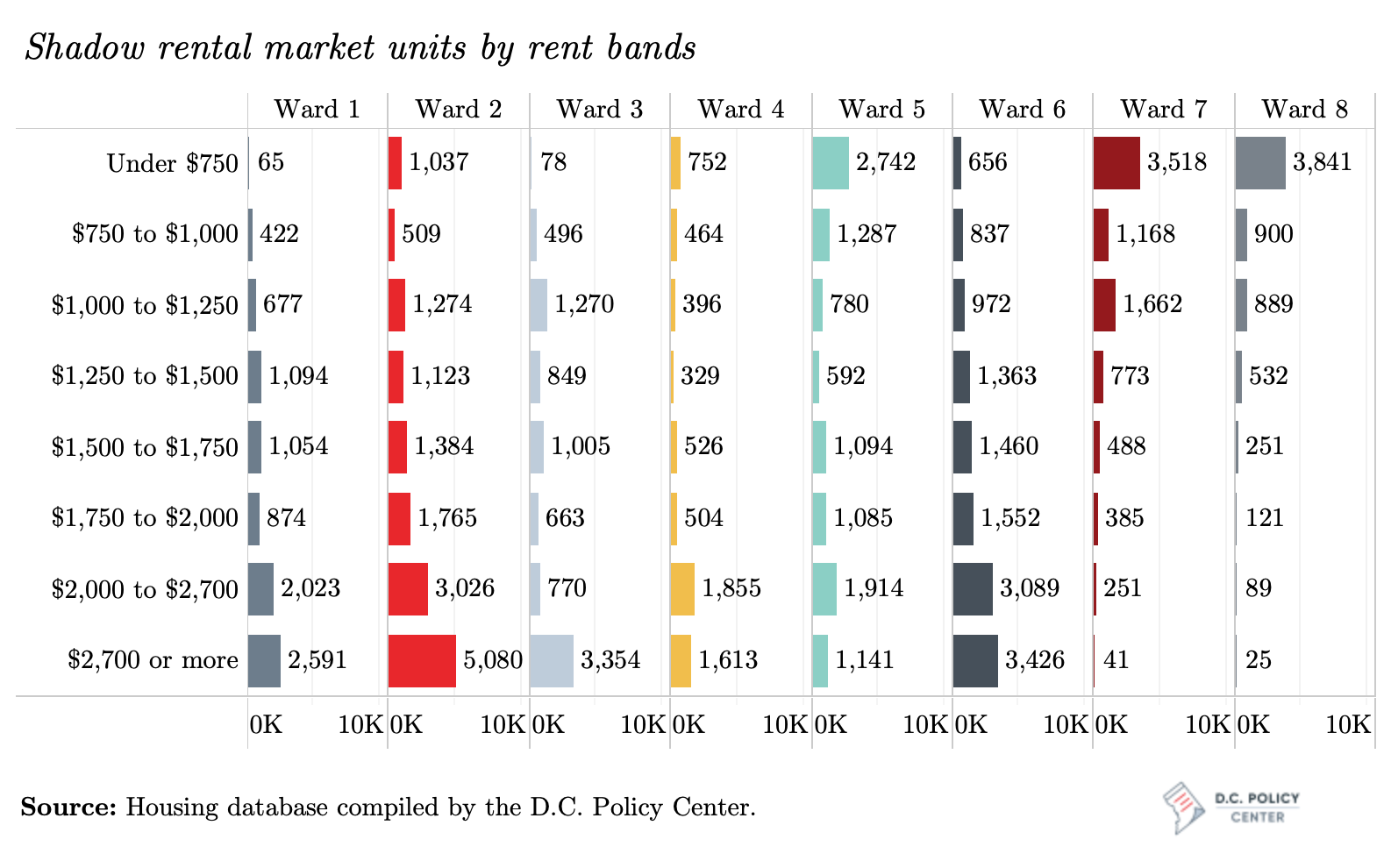

The shadow rental market provides a larger variety of units at larger variety of rents.

By offering a mix of both low-priced and high-priced units to renters, the shadow rental market relieves the pressures on the rental apartment buildings from both the bottom and from the top.

Grouping shadow rental market units by their estimated rents, this report finds an estimated 12,700 units that could potentially serve the lowest end of the rental market, with rents at or below $750 per month. Most of these units are in Wards 5, 7, and 8. There are likewise many high-priced units: an estimated 17,000 units, or approximately 22 percent of the units in the shadow rental market, likely command monthly rents above $2,700 per month, outside the affordability threshold for any household that earns less than 80 percent of Area Median Income, regardless of household size. Most of these higher-priced units are in Wards 2, 3, and 6.

Across rent-controlled apartments, where rents are higher, renters’ estimated rent burdens are lower.

This suggests that rent-controlled housing is also economically segregated, and lower rents in rent-controlled buildings have not been able bring lower-income residents into otherwise higher-income neighborhoods. But the presence of rent-controlled units in a neighborhood does appear to mitigate displacement. A larger share of tenants stays in place in census tracts where rent-controlled-units are a larger share of the housing stock, and the loss of residents of color has been slower in census tracts where a larger share of housing is rent-controlled apartments.

The District can leverage the ubiquity and the lower rents of its rent-controlled stock to increase affordability and economic inclusion.

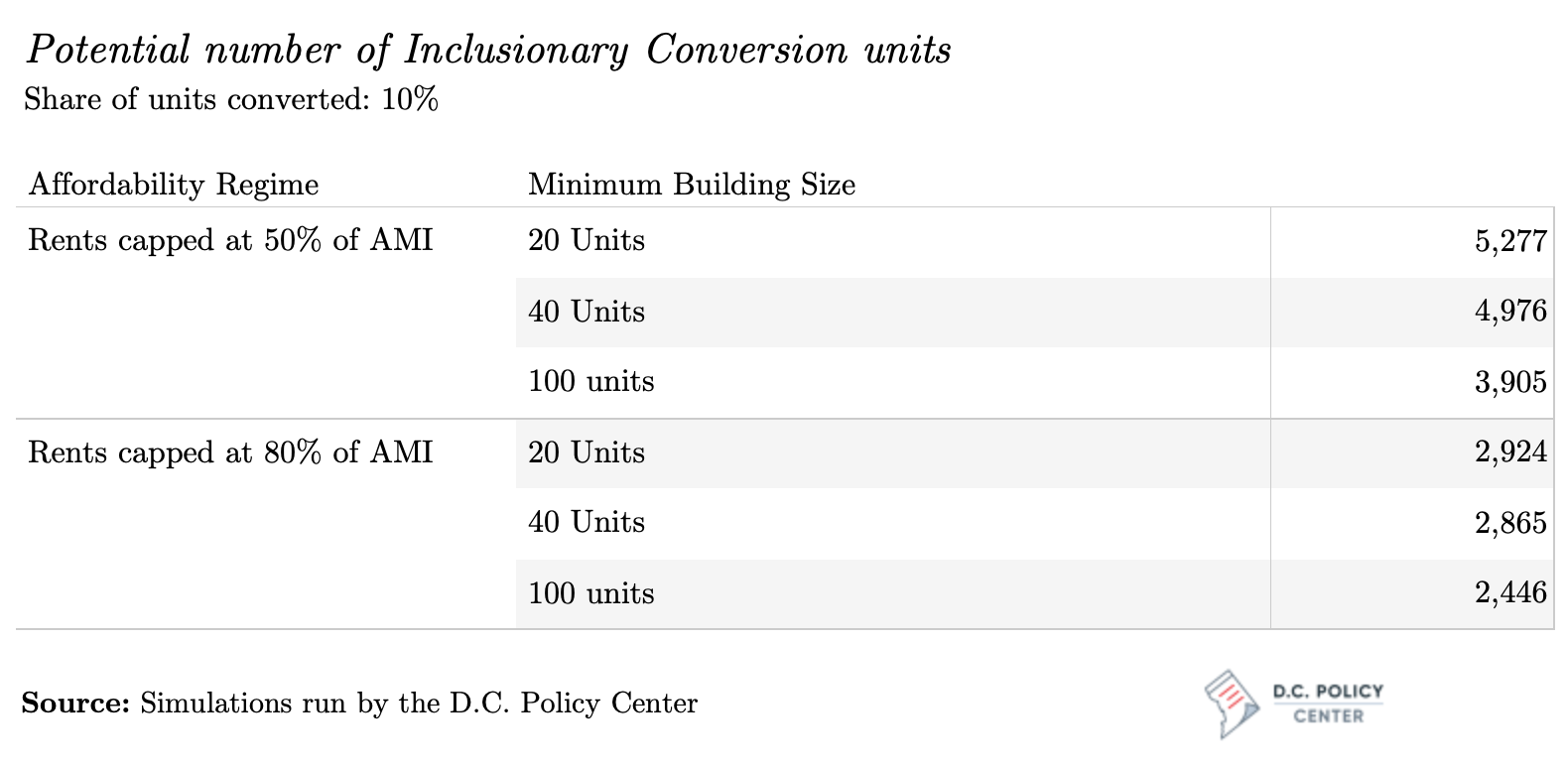

The District’s rent-controlled units have lower rents, and they are everywhere, especially in parts of the city where building affordable units has been difficult. This report considers a policy tool—called Inclusionary Conversions—that takes advantage of these characteristics to create subsidized affordable units with multi-year covenants.

Under the Inclusionary Conversion approach, the District would convert a small portion of existing rent-controlled units into designated affordable units. Once the conversion takes place, the converted unit would operate in the same way as an Inclusionary Zoning unit: the rent would be set below a certain income level that reflects the city’s affordability targets, and only households in the eligible income band would be offered the unit. In return, the landlord receives public support that is the equivalent of the difference between the rent-controlled rent and the rent considered “affordable” as not more than 30 percent of the renter’s income.

This report presents a model that can be simulated with different policy targets to estimate the number and location of units. It also estimates the costs of the program to the District under two different financing approaches: one that creates the inclusionary conversion units by providing a one-time subsidy during a capital event, such as refinancing of a rent-controlled building, much like a Housing Production Trust Fund soft loan; and one that offers annual subsidies through the life of the covenants, much like project-based local rent supplements.

Regardless of the financing approach, the Inclusionary Conversion approach follows two simple principles:

- Convert rent-controlled units into subsidized affordable housing, because rent-controlled units are everywhere, and they have relatively lower rents.

- Rather than committing an entire building for affordable use, convert a small share in each building to further establish economic inclusion without dramatically changing the overall income profile of a building.

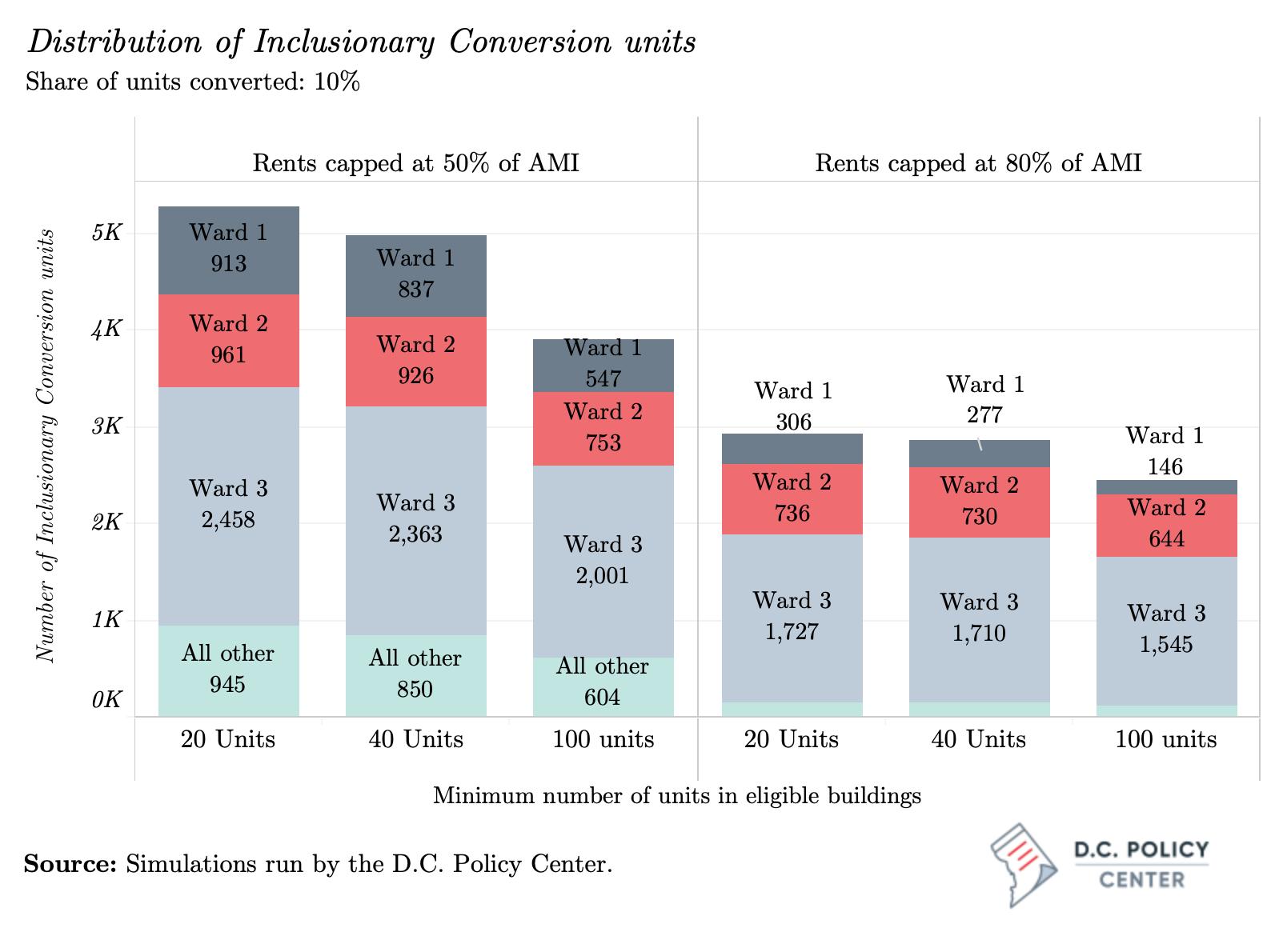

The Inclusionary Conversion approach can therefore enable the creation of new subsidized affordable rental units, especially in parts of the city that so far have not had a large amount of subsidized affordable housing. For example, if the District were to set aside 10 percent of units in rent-controlled buildings for affordable use under this program, it could generate up to 5,300 affordable units, depending on the type of affordability goal it pursued.

The Inclusionary Conversion tool would create the greatest number of affordable units in Wards 1, 2, and 3.

This outcome is partially driven by the distribution of rent-controlled apartment buildings across the city, as many of these older buildings are in Wards 1, 2, and 3. It is also partially dependent on the affordability target the city chooses to pursue. An affordability target of 80 percent of AMI, for example, would exclude many rent-controlled units in Wards 7 and 8, since rents in these two wards are already affordable at or below this income level. But were the city set the affordability target to 50 percent of AMI, more units overall would be eligible for the public subsidy (because of lower target rents) in every ward in the city.

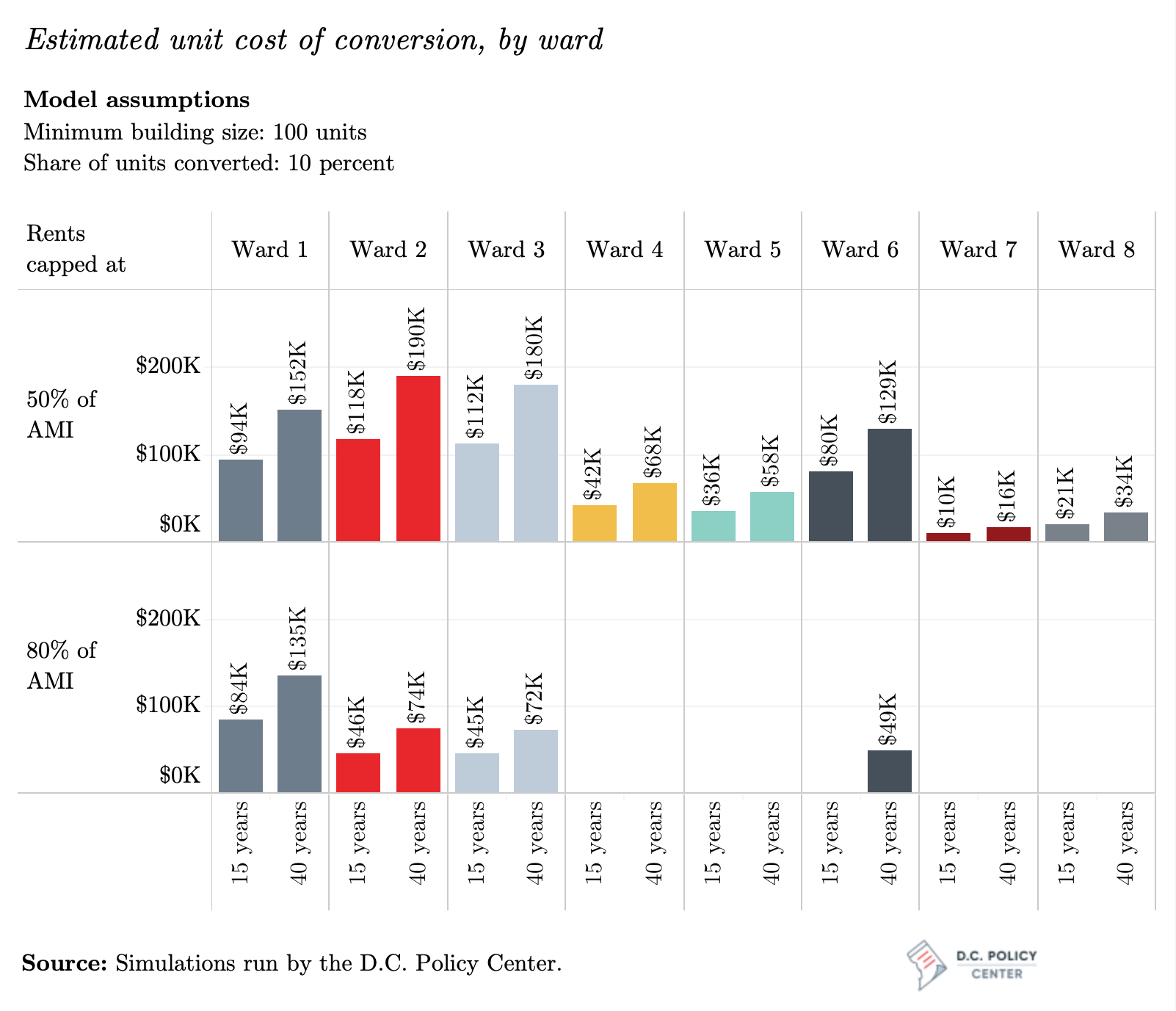

The unit costs of creating a subsidized unit under the Inclusionary Conversion approach would be much lower than what current Housing Production Trust Fund projects cost.

The unit costs of creating a subsidized unit under the Inclusionary Conversion approach would be much lower than what current Housing Production Trust Fund projects cost.

To facilitate the comparison with the Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF), we modeled the financing of the Inclusionary Conversion program in a manner similar to an HPTF soft loan, wherein the landlord receives the present value of the subsidies for the affordable units with covenants at the time of a capital event, such as refinancing. Under this approach, the estimated unit cost of converting an apartment into an affordable unit at 50 percent of Area Median Income with a 40-year covenant (most like HPTF projects) is $190,000 for Ward 2 and $180,000 for Ward 3. While not small, these are not unusual numbers as far as subsidies go for deeply affordable units in current HPTF projects. And they are well below the amount necessary to build such units in Wards 2 and 3 as new construction, even if it is assumed that there is room under current zoning to build them. While the HPTF has produced almost no units in these parts of the city because of the prohibitive costs, the Inclusionary Conversion program can do so, and produce a greater number of units.

The District could also fund Inclusionary Conversion units through annual operating subsidies, and even pay for them through a tax abatement.

There are salient differences between these two financing approaches. An annual subsidy would commit the District to annual payments over the term of the covenant, significantly expanding the operating budget for housing subsidies over long periods of time. On the other hand, the cost of a one-time financing subsidy, much like the cost of a Housing Production Trust Fund loan, is clear, concrete, and one-time, without creating any risks to the District’s financial plan. However, it also shifts the fiscal risk to the landlords: when they accept a one-time subsidy, they accept a lower resale value for their building.

The Inclusionary Conversion approach can be extended to ensure a certain number of units are delivered each year, or the number of affordable units are maximized for a given level of funding (by, for example, asking landlords to bid, as they do for HPTF loans). It can further be extended to look more like a major rehabilitation loan with the landlord committing a larger share of the building’s units for affordable use in return for a bigger cash infusion that should be used towards rehabilitation. The District can also weigh other priorities when deciding who would be funded through a potential Inclusionary Conversion program: it can incentivize, for example, buildings with larger units, buildings in different parts of the city, or buildings that prioritize other policy goals (such as green investments or closer to transportation corridors).

While this report is focused on developing the concept of Inclusionary Conversions, there are sure to be some implementation hurdles, many like those that afflict existing affordability programs. While they are not thoroughly explored herein, these include deciding who would be responsible for verifying incomes (landlords or a government agency), how eligibility existing tenants will be monitored year to year, how the Inclusionary Conversion program could interact with existing tenants’ rights laws, and how units with tenants already under the affordability limits would be treated, among others.

The Inclusionary Conversion approach could be a more efficient means of using the city’s public housing subsidies, but it will not create new units.

The Inclusionary Conversion approach presented this report is intended as a lower cost alternative to the District’s current public subsidy programs—one that can potentially create more economically inclusive neighborhoods. It is not intended to be a wholesale solution for the housing crises in the District. While creating more targeted affordability, the Inclusionary Conversions approach will not create more units to relieve the existing pressures on the District’s rental housing. More fundamental changes in the housing landscape can only be achieved with less restrictive land use practices and a better functioning regulatory system.

The District of Columbia needs a broader view of rental housing and how it fits into its overall housing strategy.

A substantive part of the District’s rental housing is dependent upon the willingness on the part of smaller landlords to keep their units in the rental market. Further, some of the policies the city is pursuing to increase housing supply (such as Accessory Dwelling Units or infill development) relies on convincing current homeowners to become landlords. The District’s rental housing policies, however, are generally focused on large rental apartments, and do not consider the constraints for and the capacity of smaller landlords in obtaining financing, meeting regulatory requirements, and working within the requirements of tenants’ rights laws. A broader rental housing policy that recognizes the importance of these smaller landlords in expanding the city’s housing supply would be a step in the right direction for the District of Columbia.

<< Back: Main publication page | Next: Chapter 1 >>