Update: The text has been updated with footnotes 2 and 3 to include context on two cited studies. (2/2/2018).

The proposed “Student Fair Access to School Act of 2017” prohibits out-of-school suspensions aside from the most extreme disciplinary incidents. The bill follows a trend of disciplinary policy reform in nearly 27 states and 50 large school districts that affects more than 6.35 million students. There are mixed signs of success: the out-of-school discipline bans are associated with a 20 percent drop in suspensions across the country from school year 2011-12 to 2013-14,[1] but quick shifts in discipline policy have also had adverse effects such as high teacher turnover in Washington state, deteriorating school climate in New York,[2] or lower academic achievement for some students without prior suspensions in Philadelphia.[3]

If the bill is enacted, the proposed partial ban would have an immediate and vast impact on the District of Columbia’s schools and students. There were 13,000 out-of-school ban incidences last year. Data on these incidences show that the proposed partial suspension ban may reduce out-of-school suspensions by as much as half. Most of this reduction will be the result of a ban on suspensions for general misbehavior. However, these students may find themselves still excluded from learning time (and continue to receive disparate treatment) if in-school suspensions replace out-of-school suspensions. Traditional public and public charter schools in D.C. do not intensively use in-school suspensions and appear to underreport them when they do. As such, a rapid transition to in-school suspensions could force schools to use a discipline tool schools are not ready to use effectively and obscure the underlying problem.

In this study, we examine discipline policies across District’s traditional public and public charter schools; estimate the number of students that could be affected by the proposed bill; and examine the school system’s ability to implement the new ban the way the ban is intended. We also look at the policies in public schools and neighboring jurisdictions that have already made efforts to reduce exclusionary discipline to discern lessons that could be useful to the District.

Proposed changes to D.C. discipline policies for out-of-school suspensions

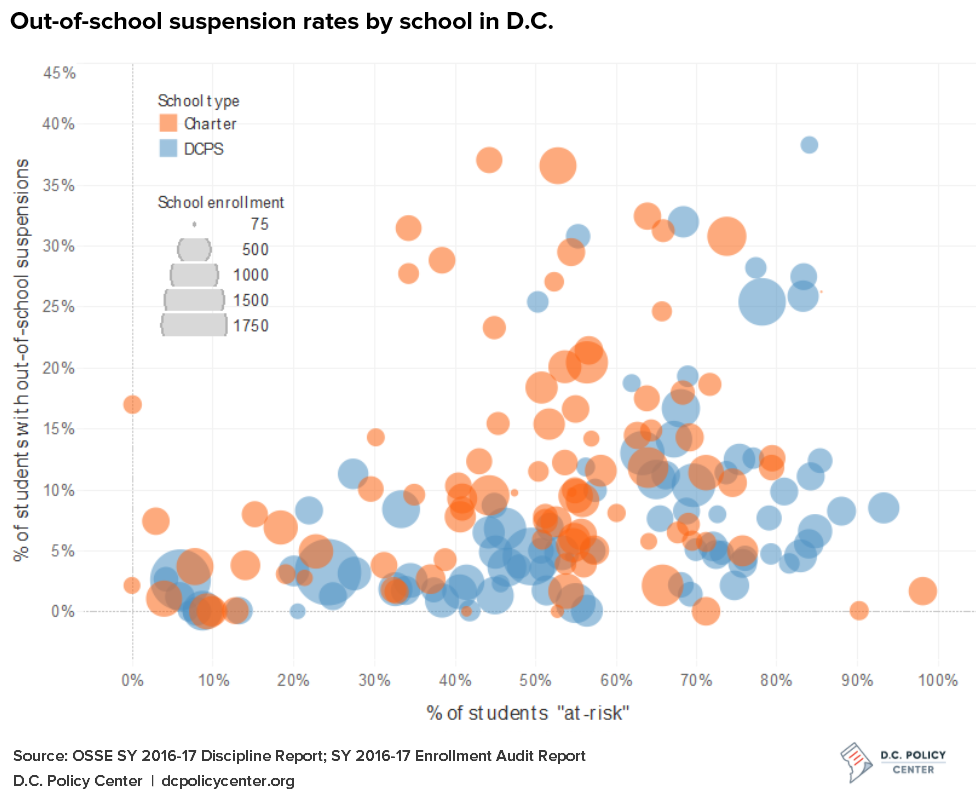

As proposed, the “Student Fair Access to School Act of 2017” would change District school discipline policies to prevent students from being excluded from school for non-serious infractions, with the ultimate goal to reduce disparities in suspension rates. Several changes focus specifically on limiting the occurrence and severity of out-of-school suspensions, with different limits placed on suspensions of kindergarten through grade 8 students and students in grades 9 to 12 (see table below).[4]

Current discipline policies differ for District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) and for each public charter school, which collectively enroll about 40 percent of students in kindergarten through grade 12.[6]

DCPS discipline policies

Current DCPS Student Discipline regulations outline behaviors that may result in out-of-school suspensions. In elementary and middle schools, the proposed legislation would dramatically reduce the number of suspensions as it bans out-of-school suspensions for these students except in cases of potential bodily harm or other serious circumstances. At the high school level, the key change would ban out-of-school suspensions for primarily behavioral incidents that are currently eligible for suspension.[7] These include causing disruption on school property or at any DCPS-sponsored or -supervised activity (for example, banging on lockers or other surfaces in a loud manner, yelling loudly, throwing objects refusing to comply with multiple requests to go to class, and other behaviors); [8] obscene, seriously offensive, or abusive language or gesture, or engaging in reckless behavior that may cause harm to self or others (including play fighting, running in the hallways, or chasing others).

Other restrictions on out-of-school suspensions in the bill are fairly similar to present DCPS policy. These include not using out-of-school suspensions for lateness, unexcused absence, or dress code violations,[9] or for non-school-related behavior that happens off-campus.[10]

Public Charter School discipline policies

Pubic charter schools have autonomy over their academic approach including discipline policies, which means there is no standard discipline policy across all public charter schools. Charter application guidelines for groups applying to open a new school state that the DC Public Charter School Board is “unlikely to approve applications for schools with discipline policies that rely solely on exclusion to manage student behavior and/or that are likely to result in high rates of suspensions and expulsions.”

However, as the Washington Post has reported, some of the District’s charter school networks have discipline policies that allow out-of-school suspensions for relatively minor and/or subjective reasons. The proposed bill would have a varying degree of effect on charter schools depending on how permissive each school’s discipline policy is with respect to out-of-school suspensions.

D.C.’s ongoing efforts to reduce out-of-school suspensions

Many of the several strategies the bill offers to purposefully reduce suspensions are similar to ongoing initiatives. For example, OSSE currently provides trainings on “positive behavioral interventions and supports, trauma informed care, youth mental health first aid, and nonviolent crisis prevention,” shares resources on non-discriminatory discipline practices, and organizes a Restorative Justice Community of Practice, which are all included in the proposed bill as ways to promote trauma-informed education settings.[11] Increasing resources to strengthen these existing programs would be an important contribution. The bill does include new support to complete trauma-informed postsecondary degrees or certificate programs, which is a very important addition.

Some schools in D.C. are already shifting away from suspensions, and the city’s suspension rate has declined by five percentage points the past five years. Several are participating in OSSE’s three-year-old Restorative DC program that provides tailored support on restorative practices to a cohort of schools.[12] Other schools deliberately intend to reduce suspensions according to their discipline policies. Kingsman Academy PCS, which has a philosophy to serve students at risk of dropping out of school, made the commitment to eliminate suspensions in December of 2016, and has succeeded in suspending zero students compared to a suspension rate of 7.2 percent at peer schools. Ron Brown College Preparatory HS, the new public high school designed for young men of color, all but prohibited suspensions in its first year and has a suspension rate of 4.8 percent compared to 16.0 percent of peer schools.

Even with OSSE and some schools undertaking this important work, out-of-school suspensions persist. What is the scale and disproportionality of exclusionary discipline that the bill prohibits?

Current disparities in suspensions at D.C.’s schools

In school year 2016-17, 7.4 percent of all students received a suspension, which involved about 13,000 suspension incidents according to OSSE’s State of Discipline: 2016-17 School Year report (students who are suspended multiple times only count once toward the overall rate). Students received more out-of-school suspensions than the previous school year, although reported in-school suspensions decreased.

As context, this discussion of suspension rates is likely to be influenced by underreporting and may be higher than official rates. Although both DCPS and DC PCSB have reported declining suspension rates in recent years, a Washington Post investigation suggests that the reported data may not tell the whole story. The Post’s 2017 analysis of seven DCPS high schools found that many students were “unofficially suspended,” barred from classes without being reported as receiving an out-of-school suspension; instead, these students were falsely recorded as present, attending an “in-school activity,” or “unexcused absent.”[13] Reporters found that most out-of-school suspensions (in terms of days of suspension) are not officially reported at the seven DCPS high schools they examined; at one high school, the rate of suspensions that were officially recorded was as low as seven percent. The Post later reported that OSSE has been aware of the practice of undocumented suspensions since at least 2010.[14]

Disparities in suspensions by student characteristics

OSSE’s annual report finds continued disparities in out-of-school suspensions by race and ethnicity. Black students are not only more likely to receive suspensions compared with Hispanic and white students, but those who were disciplined were more likely to miss multiple days of school and more likely to receive multiple suspensions. Simply comparing the student population with students who received suspensions shows stark differences by race: While black students made up 67.6 percent of the total student population for D.C. public schools and public charter schools in SY16-17, they accounted for 92.4 percent of students receiving out-of-school suspensions. Meanwhile, white students made up 9.7 percent of the student population, but made up less than one percent (0.7 percent) of students receiving out-of-school suspensions.[15]

OSSE’s report also includes a logistic regression model that accounts for other factors that could also affect suspension rates. The report found that African American students are 7.7 times more likely to have received at least one out-of-school suspension when compared to their white counterparts when controlling for grade in school, sex, English learner status, economic disadvantaged status, at-risk status, Special Education status, or attending more than one school during the 2016-17 school year.[16] The report also found persistent disparities in suspension rates along gender and socioeconomic status.

Variation in out-of-school suspensions by school factors

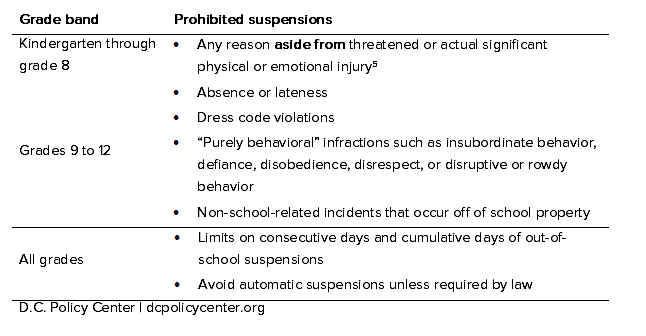

There is great variation in reported out-of-school suspension rates by school. Some schools don’t report any out-of-school suspensions, while others report that almost four in ten students received an out-of-school suspension in the 2016-17 school year.

The chart below shows out-of-school suspension rates as reported in OSSE’s 2016-17 school discipline report. Public charter schools are in orange, while DCPS schools are in blue. The size of the circle is determined by the school’s audited enrollment numbers (which may differ from the number of students used to calculate the school’s suspension rate).

Higher out-of-school suspension rates for middle school, ninth grade

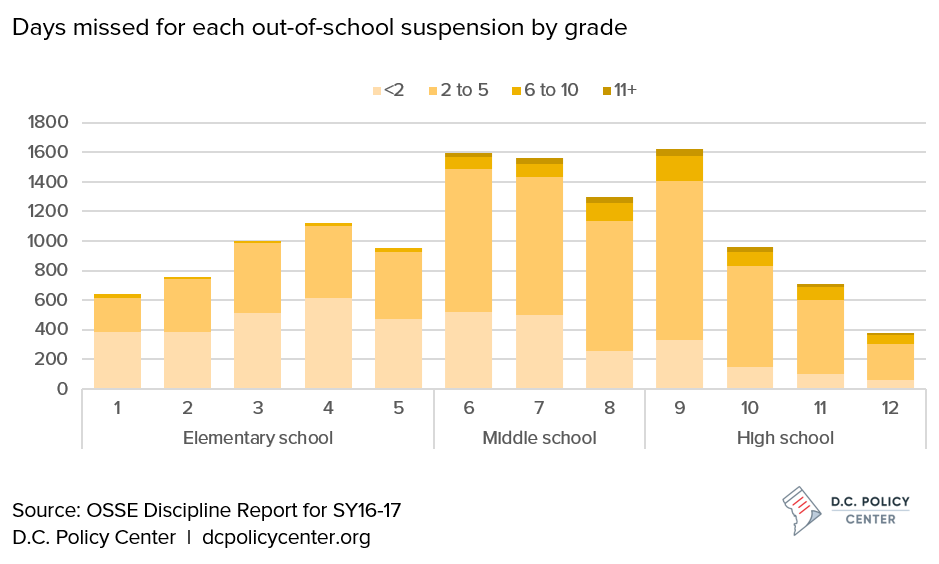

The total number of out-of-school suspensions reported for D.C. public schools and public charter schools climbs though elementary school before increasing sharply in middle school and the first year of high school; the number of out-of-school suspensions reported drops rapidly every grade after for grades 10-12. However, OSSE finds that the number of instructional days suspended students miss increases steadily by grade: more than half of suspensions for students below fifth grade are for less than two days, but most suspensions given to students in older grades are typically between two and five days, with an increasing proportion of longer suspensions (six to ten days) through the end of high school.

Offense types resulting in out-of-school suspensions

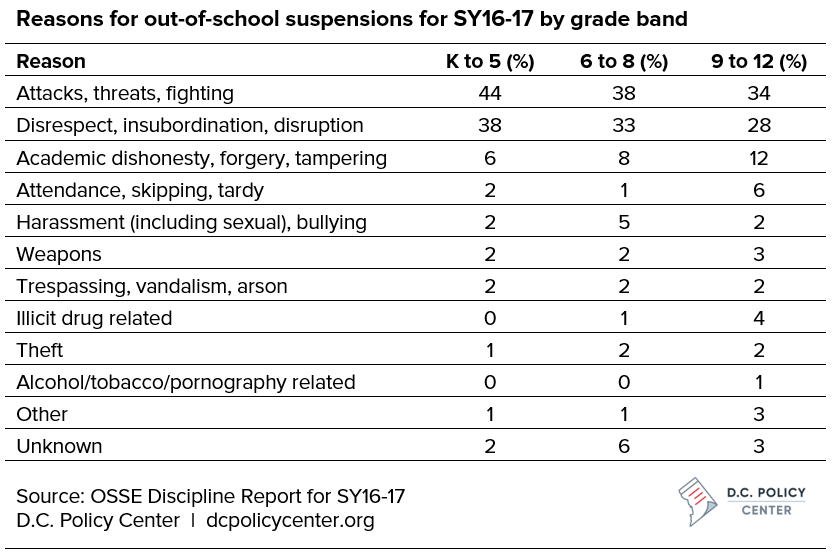

The most common infractions resulting in official out-of-school suspensions in D.C. public schools and public charter schools for the 2016-17 school year were those categorized as “attacks, threats, [or] fighting” and “disrespect, insubordination, [or] disruption,” which are very likely to be banned under the bill. The share of these types of offenses decreases for older grade bands as other types of offenses (such as academic dishonesty) become relatively more common.

Potential impact of the proposed bill

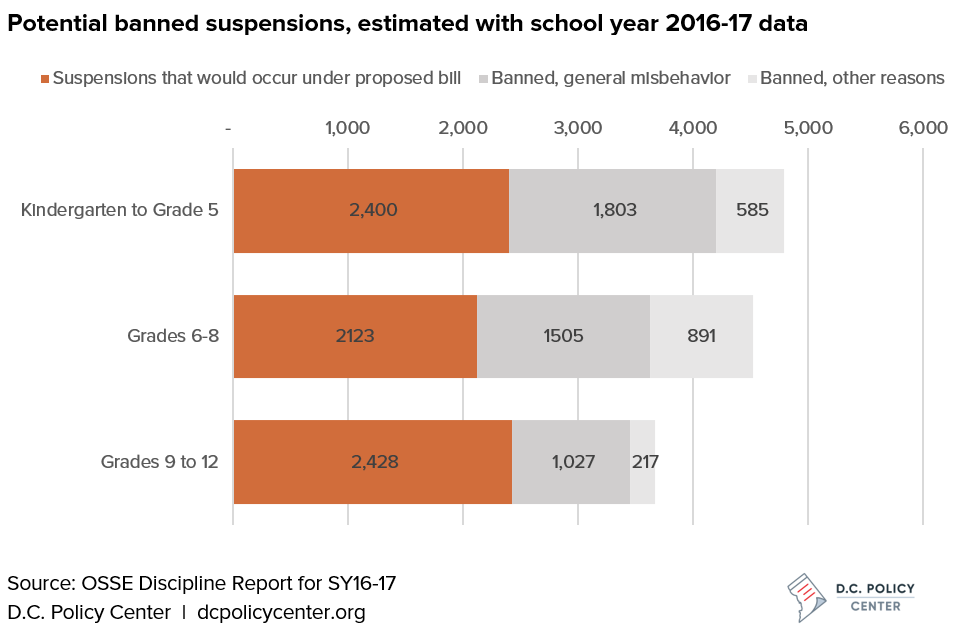

The proposed legislation would reduce eligible reasons for out-of-school suspensions, with different impacts for students in kindergarten through grade 8 and high school students. If the policy change is implemented with fidelity, our most conservative estimate is that 46 percent of out-of-school suspensions would be subject to the ban.[17]

Kindergarten through grade 8 suspensions would represent 80 percent of this decrease if out-of-school suspensions are only allowed in cases of threatened or actual “significant” physical or emotional injury.[18] To estimate the number of prohibited suspensions, we assume that any kindergarten through grade 8 suspension would be allowed in related categories as outlined by OSSE (weapons; harassment (including sexual) or bullying; trespassing, vandalism, or arson; and attacks, threats, or fighting) and banned for other less serious categories (theft; illicit drug related; disrespect, insubordination, or disruption; attendance, skipping, or tardy; alcohol, tobacco, or pornography related; and academic dishonesty or tampering). For high school students, a ban on general misbehavior suspensions would result in almost all of the decrease in suspensions. To calculate the number of prohibited high school suspensions, we assume that suspensions would be allowed in any category aside from “disrespect, insubordination, [or] disruption” and “attendance, skipping, [or] tardy.”

Interestingly, middle school is particularly critical as there are more suspension incidents per grade in grades 6 to 8 than elementary or high school grades. Middle school students may mature at different rates, both physically and emotionally, and the time of general transition and change contributes to more conflict within the classroom and elsewhere at school. And while some students are more likely to act in disrespectful or disruptive ways, their perceived maturity may also affect how teachers and administrators respond to their behavior. National research from Brookings and the American Psychological Association shows that black students—especially black boys—are more likely to be perceived as exhibiting poor behavior than white students, are more likely to be perceived as older than they are, and are more likely to be seen as culpable for misbehavior.

A key question moving forward is whether these students should be treated more like elementary school students (with more reasons for suspensions banned) or high school students (with fewer restrictions on suspensions). In both grade bands, general misbehavior (disrespect, insubordination, disruption) account for 70 percent of the suspensions that would be banned.

Additional suspensions would be banned due to the caps on consecutive and cumulative days of suspension, but data are not sufficient to estimate these reductions. Based on a 48 percent reduction in the total number of suspension incidents, the overall suspension rate could decrease from 7.4 percent to 4.8 percent assuming that students are not more likely to have multiple offenses in any one category.

Potential unintended consequences of the proposed bill

If approximately 48 percent of out-of-school suspensions would be banned under the proposed legislation, this would mean a huge shift in how schools discipline students. Suspension rates would decrease, especially for African American students. As mentioned above, the proposed bill calls for OSSE to continue much of its ongoing work to promote trauma-informed educational settings and with the additional option of postsecondary degree or certificate programs. It is unclear what new resources will be in place to implement these changes in a meaningful way.

If schools simply comply with the bans on out-of-school suspension without adequate supports to shift mindsets, it is possible that in-school suspensions will be used as the closest alternative to remove students from classrooms. For example, after Chicago implemented policies to reduce instructional time lost to suspensions, in-school suspensions doubled for African American students. This is alarming because D.C. doesn’t have a full picture of current in-school suspension, and if more schools start to substitute this practice for out-of-school suspensions, there is a real risk of exclusionary discipline persisting but obscured from view.

From looking at current student handbooks, 85 percent of schools (public charter and DCPS) serving elementary, middle, and high school students mention in-school suspension as a potential disciplinary action. However, about 70 percent of these schools with in-school suspension as a consequence in their student handbook did not report any in-school suspensions (113 out of 164) in school year 2016-17. Just 14 percent of schools with an in-school suspension policy reported more than 5 in-school suspensions. By comparison, all 193 elementary, middle, and high schools include out-of-school suspensions as a potential discipline option, and 81 percent of these schools report more than 5 suspensions.

Reporting of in-school suspensions is on the decline, with a decrease over the last two years while the number of out-of-school suspensions increased. There is also evidence of non-reporting, with nine LEAs reporting no in-school suspension for discipline purposes but reporting 704 in-school suspensions for attendance purposes. Before this bill moves forward, the city needs a better understanding of how many students experience in-school suspension and what in-school suspensions look like at each school, as in-school suspensions are defined with varying degrees of detail. Some schools’ policies only mention in-school suspensions in passing, and others go as far as to define what an in-school suspension looks like in practice.

Policies and practices in other school districts

Many other school districts across the country are taking steps to eliminate discriminatory discipline practices that contribute to lower outcomes for minority and low-income students, but some districts have run into significant implementation challenges as student and teacher behavior does not change overnight. For example, Philadelphia attempted to reduce suspensions through a reform that prohibited suspensions for minor behavior issues of failure to follow classroom rules and profane language (similar to D.C.’s proposed ban) and allowed school leaders greater autonomy around disciplining more serious infractions. However, a recent study, Rolling Back Zero Tolerance: The Effect of Discipline Policy Reform on Suspension Usage and Student Outcomes, found that the changes did not reduce the overall use of suspensions, and that unexcused absences increased while academic achievement declined.

Implementing effective partial suspension bans and restorative justice calls for school community buy-in from students, administrators, and parents or guardians. In addition, two structural components, adequate mental health professionals and healthy school environments are particularly necessary to implement the proposed partial suspension bill with success in D.C. For more background on the policy, see “Proposed Partial Suspension Ban Requires Shift in Mindsets.”

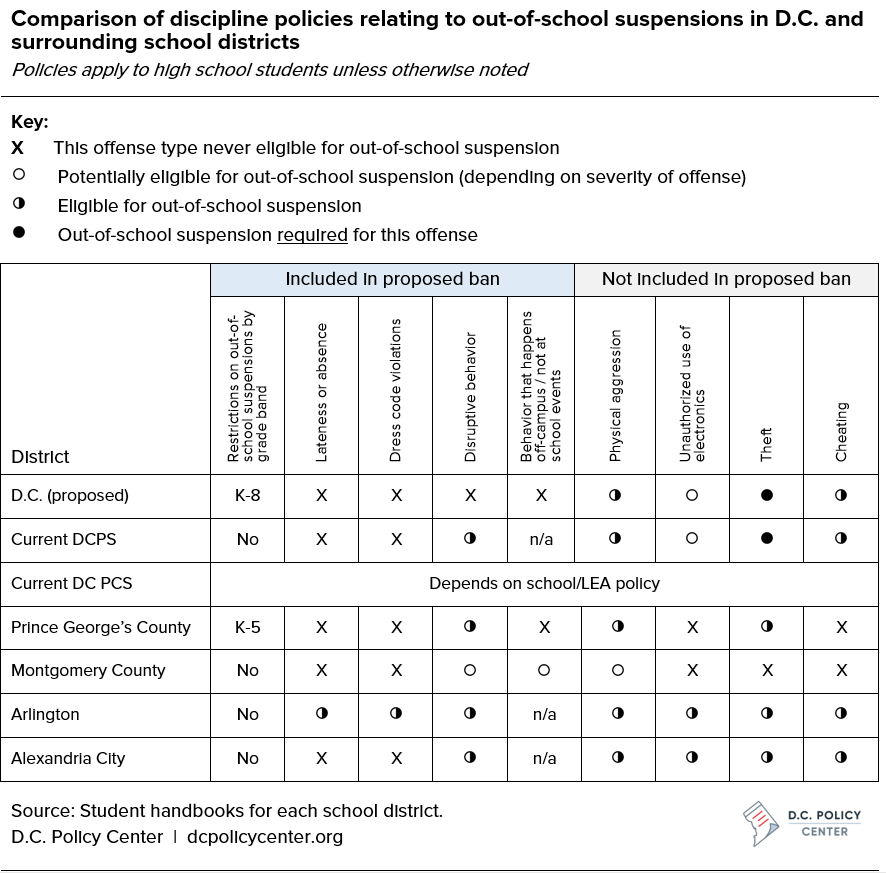

School discipline policies in surrounding school districts

A review of discipline policies in surrounding school districts shows that the broad strokes of current DCPS policies (public charter school policies differ by school) around out-of-school suspensions are fairly similar to Prince George’s County, Montgomery County, and Alexandria City public schools. None of these districts officially allow out-of-school suspensions for tardiness, unexcused absence, or dress code violations, but do allow out-of-school suspensions for various types of “disruptive behavior” (out-of-school suspensions are allowed for any type of infraction in Arlington public schools).

Similar to the proposed ban, Prince George’s County public schools differentiates between lower and upper grade bands in allowing out-of-school suspensions.

Unlike most other jurisdictions (including current DCPS policy), Prince George’s County only allows out-of-school suspensions for students in kindergarten through sixth grade in cases of attacking another student or adult, causing serious bodily injury, or for other serious offenses (such as arson, bomb threats, possession of explosives, or sexual misconduct). However, Prince George’s County applies the same discipline policies to middle school students and high school students—unlike the proposed D.C. bill, which groups middle school students with elementary school students, and bans suspensions aside from those that involve significant bodily injury or emotional distress.

Suspension rates in surrounding districts

To see how these policies relate to suspension rates, we use data from the 2013-14 school year. This is the most recent data available from the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights Data Collection database, which includes comparable statistics for all schools and districts in the country. Therefore, some of the data cited in this section will differ from more recent suspension rates and enrollment numbers cited elsewhere in this analysis.

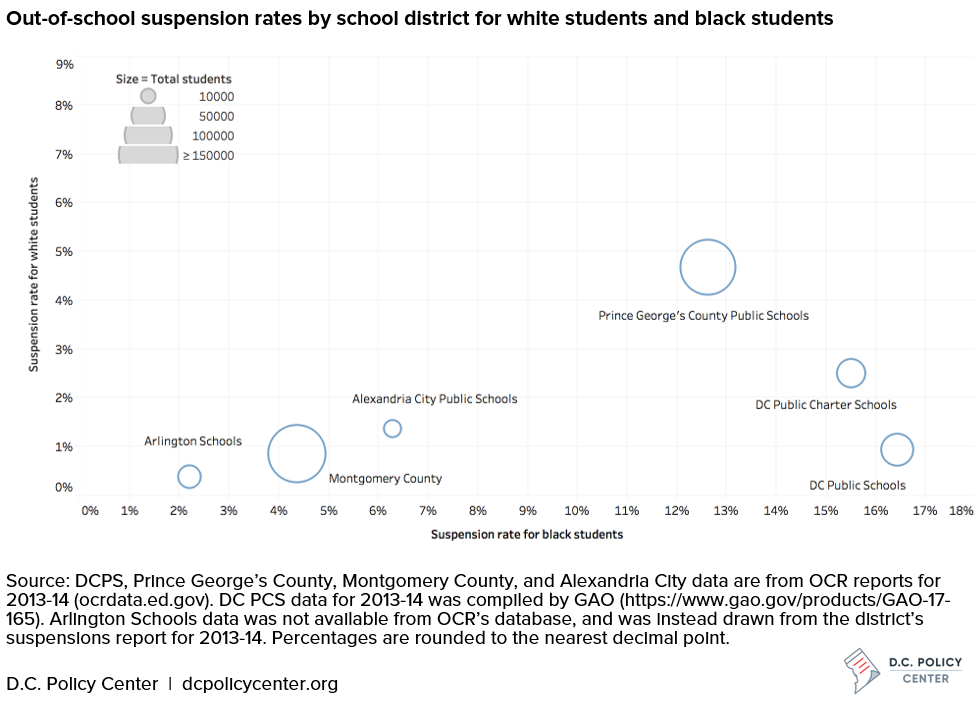

All surrounding school districts have notable disparities in out-of-school suspension rates between black and white students.[19] However, as previous research has shown, DCPS has one of the largest gaps, in part due to how few white students ever receive out-of-school suspensions.

- DCPS and DC public charter schools had similar overall suspension rates in the 2013-14 school year, and similar suspension rates for black students. Because DC public charter schools had a higher overall suspension rate among white students, they had a lower overall gap between black and white students’ suspension rates.

- Prince George’s County’s overall suspension rate (9.8 percent and 12.6 percent for African American students) was lower than D.C. schools, but higher than other districts. While its district-wide suspension policies for older students are fairly similar to current DCPS policy, Prince George’s County allows out-of-school suspensions for students in grades K-5 only for more serious offenses.

- Montgomery County had a very low overall suspension rate: about 2 percent overall, and just 4.4 percent among black students. It tends to be most restrictive of which actions can result in an out-of-school suspension.

- Arlington schools’ handbook does not explicitly prohibit schools from issuing out-of-school suspensions for any of the behaviors included in this analysis. Arlington schools reported a very low overall suspension rate (0.8%) in the 2013-14 school year and 2.2 percent for African American students.

- Alexandria City’s discipline policies are very similar to current DCPS policy for out-of-school suspensions. Alexandra City had a fairly low overall suspension rate (3.7 percent and 6.3 percent for black students).

Key questions for D.C. policymakers

The Student Fair Access to School Act of 2017 has the potential to cut out-of-school suspensions by about half, but the city should look to other districts like Chicago and Philadelphia as well as D.C. schools such as Kingsman Academy PCS and Ron Brown College Preparatory HS to anticipate unintended consequences of a top-down discipline reform. Here are some key policy issues to consider when deciding whether this bill is a good fit for D.C.’s schools.

- The proposed bill doesn’t explicitly provide additional programs for implementing trauma-informed education settings aside from facilitating postsecondary degrees or certifications. All other strategies mentioned by the bill seem to be in effect already. Additional resources are necessary to shift educator and administrator behavior.

- In-school suspensions are not prohibited by the bill, and there is a real risk that schools (especially without additional supports) will simply replace out-of-school suspensions with in-school suspensions. An increase in in-school suspensions is an issue for three reasons. First, this will continue exclusionary discipline. Second, the city may lose information on how exclusionary discipline disproportionately affects certain students due to current underreporting issues. Third, student discipline may be less uniform as in-school suspension practices vary by school and the process is not well-documented publicly for some LEAs.

- Middle school students would be especially impacted by the bill. There are more suspensions per grade in grades 6 to 8, and these grades are currently included in the more restrictive suspensions ban in all instances except causing significant bodily harm or emotional distress. Any reform should pay close attention to middle school grades, particularly as these years set the stage for high school behavior patterns.

The D.C. Policy Center will testify at a public hearing for the Student Fair Access to School Act of 2017 on January 30, 2018. You can read our testimony here.

Notes

[1] Eden, M. (2017). “School Discipline Reform and Disorder: Evidence from New York City Public Schools, 2012-16.” Manhattan Institute: New York, NY.

[2] This study uses a distribution in differences analysis of self-reported survey results to look at changes in school climate. For more background on how school safety is perceived and tracked in New York after the reforms, see New York charter wars enter a school safety phase.

[3] This study relies on a difference in difference approach using three years of academic data, and its findings are associational in nature. For findings on school environment changes during the later years of Philadelphia’s school discipline reform, see Discipline in Context: Suspension, Climate, and PBIS in the School District of Philadelphia.

[4] D.C.’s “Pre-K Student Discipline Amendment Act of 2015” already bans suspensions in pre-kindergarten aside from those involving bodily injury.

[5] The bill defines “significant bodily injury” as an injury that requires hospitalization or immediate medical attention.

[6] DC Public Charter School Board, Facts and Figures.

[7] Office of the Chief of Schools/Youth Engagement (2015). “Chief of Schools Guidance Regarding Select Chapter 25 Provisions, Behavior, and Disciplinary Responses.” District of Columbia Public Schools.

[8] Ibid., page 8.

[9] While lateness, absence, and dress code violations cannot result in OSS, they can result in in-school suspension.

[10] For more information, see DC Municipal Regulations for District of Columbia Public Schools, Chapter B24, Dress Codes/Uniforms (under no circumstance shall a student who fails to abide by a mandatory uniform policy be given out-of-school suspension or otherwise be barred from attending school, but a fourth offense of a mandatory uniform policy may subject a student, at the principal’s discretion, to on-site suspension).

[11] Office of the State Superintendent for Education, State of Discipline: 2016-17 School Year report.

[12] In school year 2016-17, these schools include Ballou High School, Luke C. Moore Alternative High School, Columbia Heights Education Campus, Hart Middle School, César Chávez PCS for Public Policy – Parkside Middle School, Kelly Miller Middle School, Thomas Elementary School, and SEED PCS.

[13] For more information on the Post’s methods, see “How The Washington Post examined suspensions in D.C. Schools.”

[14] OSSE has also reported issues with reported in-school suspensions as well, with many schools showing in-school suspensions in their attendance records, but not in officially reported discipline statistics. For more information, see OSSE’s State of Discipline: 2016-17 School Year report.

[15] In addition, Hispanic or Latino students made up 19.0 percent of the student population, and received 6.1 percent of out-of-school suspensions according to OSSE’s State of Discipline: 2016-17 School Year report.

[16] All likelihoods noted in text are statistically significant at the 99.9 percent confidence level (p<.001, OSSE’s State of Discipline: 2016-17 School Year report).

[17] This estimate assumes that for categories with multiple types of offenses with differing levels of severity, the most extreme offense type would be counted. For instance, the category “trespassing, vandalism, or arson” is counted as “eligible for out-of-school suspensions” for students in grades K-8 even though it includes offenses (trespassing and vandalism) that would likely not be eligible under the proposed legislation, because it does include the more serious offense of “arson.”

[18] The bill defines “significant [physical] injury” as an injury that requires hospitalization or immediate medical attention.

[19] Source: DCPS, Prince George’s County, Montgomery County, and Alexandria City data are from OCR reports for 2013-14 (ocrdata.ed.gov). DC PCS data for 2013-14 was compiled by GAO. Arlington Schools data was not available from OCR, and was instead drawn from the district’s suspensions report for 2013-14. Percentages are rounded to the nearest decimal point.

Chelsea Coffin is the Director of the Education Policy Initiative at the D.C. Policy Center.

Kathryn Zickuhr is the Deputy Director of Policy for the D.C. Policy Center.