By Laura Wilson Phelan and Lee Teitel

After centuries of exclusion and segregation within the American education system, major policy efforts in the last 60 years have focused on desegregating schools in terms of getting a diverse set of students into school buildings. In some American cities today, desegregation also occurs as neighborhoods gentrify and families from diverse economic and racial backgrounds attend the same schools. The D.C. Policy Center’s recent report, “Landscape of Diversity in D.C.’s Public Schools,” reveals that, while segregation persists in many areas of the city, school demographics are slowly becoming more diverse. The report also points out that bringing students physically together into the same space is necessary but insufficient to create truly integrated, equitable, and inclusive schools.

Through this post, we contribute our experience in building integrated schools as the founders of two organizations. The Reimagining Integration: Diverse and Equitable Schools (RIDES) project at the Harvard Graduate School of Education seeks to disrupt systemic inequality in America’s schools by building individual and team capacity to tackle race and racism, and supporting the use of improvement tools, practices and examples that help schools, districts, and charter management organizations promote diversity, equity, and true integration. Kindred is a nonprofit in D.C. that builds relationships among parents of diverse backgrounds and mobilizes them to work together to advance equity in their schools.

Our experience has been that the vast majority of influencers within a school community—the District or charter management organization, school leaders, teachers, students, and families—want to create the conditions where all students thrive, but have had limited tools to do so. We share here that to advance equity, the individuals working in school communities must think systemically about what true integration means, and in doing so, address the roles of ideological, institutional, interpersonal, and internalized racism in order to realize the promise of diverse schools.

Moving from desegregation to integration

Many publications about diverse schools use the terms “integration” and “desegregation” interchangeably, viewing this work as simply moving bodies from one school to another and treating all movement as equal. But they aren’t. Data show that even with the advances in racial equality our country has experienced in recent history, the overwhelming concentration of wealth continues to be among white families. This wealth comes with connections to influential actors within our public school system and myriad other benefits that act as buffers against all types of risks that children experience.[1] Within diverse schools, teachers are more likely to build social capital with parents from middle- and upper-income backgrounds, which inclines them unintentionally to favor the children of parents from these backgrounds, which further isolates parents from non-dominant cultures.[2]

When even a small number of influential, connected, and often white families enters a school, they shift the school’s social dynamics. They typically bring with them connections to influential individuals, as well as expectations grounded in their own school experience about what that school experience should be for their child. This influence can lead to seemingly good things, such as the school receiving more resources than it had before. But it also often means that this set of families carries more authority and influence than the families without those connections and wealth. When parents exercise that power without inclusion of the voices of families with fewer connections and who are often furthest from opportunity, it can lead to policies and resource distribution that help their child more than children from marginalized communities, further exacerbating inequity.

In their book, Despite the Best Intentions: How Racial Inequality Thrives in Good Schools, Amanda E. Lewis and John Diamond chronicled this exact phenomenon in a diverse midwestern high school. Over the course of five years, they tracked day-to-day interactions of students and families with school staff. Through interviews and observations, they documented the deferential treatment white families received over families of color in the form of lax enforcement of school rules and easier entry into tracked courses such as honors and AP. The researchers found that white students received this preferential treatment sometimes without anyone asking for it because school staff anticipated that the families of those students would seek it. While students of color and their families noticed this, many school staff didn’t realize they were favoring white students until Lewis and Diamond’s research team asked them about it. Through these behaviors of school staff and white families, learning outcome differences between white students and students of color in this diverse school persisted.

At Kindred, we have found similar patterns in diverse D.C. elementary schools. Unconsciously, security guards stop families of color at the door more frequently than white families. School-based practices such as the times school meetings are held, what gets translated (and how), and the way the parent-teacher organization is run favor privileged families over those furthest from opportunity. These practices alienate families who are not a part of dominant culture, which decreases the information they receive to help their student succeed, thus further disadvantaging them.

School-based policies are often created with the best of intentions, but without understanding the perspectives of families from low-income households and/or different cultural experiences than the individuals creating the policy. For example, a partner school of ours recently adopted the policy of “say goodbye to your children at the front door to the school,” rather than parents and caregivers walking children all the way to the classroom. The core principle behind the policy—to maximize learning time—is clearly in the best interest of children’s academic learning, but there is a cost to families who may be intimidated to reach out on their own to families and teachers of higher social stature. When dropping children at the front door, parents miss daily informal interaction with other parents of different backgrounds, as well as with the classroom teacher. They miss the opportunity to build relationships through those bonds that translate into feeling more comfortable reaching out to other parents and the teacher for help. Because D.C. schools admit students through lottery from across the city, families in this school do not necessarily live in the same neighborhood with each other. Therefore, these morning interactions at school are a critical time to build these bonds. Removing this opportunity to build relationships informally without providing complementary opportunities to do so may adversely impact those who rely on this as their main way to get information about how to support their child.

Seemingly small, well-intentioned shifts, usually designed by school staff who have long operated as part of the dominant culture, can exacerbate opportunity differences among students from marginalized backgrounds and their more privileged peers. We empathize with educators who strive to serve all children well, and understand that putting in place practices that meet the needs of all families and their students may feel like stepping around landmines. But it doesn’t have to feel this way. When schools center the ideas and experiences of those furthest from opportunity whenever making a decision and/or implementing a policy, they are able to put in place the practices that will advance equity and inclusion. Getting there requires that the entire school community work together to dismantle the effects of racism and oppression.

What does it mean to build community at diverse schools?

Examples from Kindred and RIDES, two organizations working to make desegregated schools truly integrated, show how to build intentional community amidst changing demographics. Both approaches focus on bridging understanding among stakeholders of varied backgrounds and roles, creating shared purpose, and connecting educators with students and their families.

Kindred

At Kindred, we work with school leaders and families on centering the voices of marginalized families through dialogue. In dialogue groups, parents build shared meaning about the education they want for their children by learning about the diverse experiences of other parents in the school. Parents from diverse backgrounds explore their experiences with education, their hopes and fears for their children, the history of systemic racism, and what it means to have families with such different experiences in the same school. Through this process, parents build trust and put forward and act on new ideas about how to address inequity in their school. Concurrently, Kindred works with the school leader to develop practices to engage these families as leaders in driving the ideas behind change in their school.

Two external studies of Kindred’s program have shown that it is working. Parents in Kindred dialogue groups are building empathy as well as their efficacy in supporting their child’s growth. Parents go on to play leadership roles in their school communities to advance equity, including taking initiative to address barriers to opportunity. At one Kindred partner school, for example, a group of diverse parents collects excess unused whole fruit and milk from breakfast and lunch and distributes them to families for free. In doing so, they are both reducing food waste in the school and meeting the needs of a group of families who, during the dialogue process, expressed the need for additional food at home. What’s more, because the group doing this work is diverse and talks openly about supporting each family’s needs, they are destigmatizing asking for help at the school, which addresses a key barrier among disadvantaged families to their children receiving the support they need academically, physically, and socio-emotionally.

RIDES

At Harvard’s Reimagining Integration: Diverse and Equitable Schools Project (RIDES), we are conducting research and developing a variety of tools and processes to help schools become places where all children learn at high levels, feel included, appreciate their own and other cultures, understand racism, and work to dismantle it. Three key lessons stand out among the many things we are learning:

We need a clear and broadly owned definition of integration that distinguishes it from desegregation. In its start-up year, RIDES convened over 100 parents, students, educators, and community members and asked them what would positively attract them to attend, work in, or send their children to a diverse school. When the responses were analyzed and combined, they led to what we think of as the ABCDs of integration:

- Academics: All students have strong academic preparation, capitalizing on and connecting to students of all backgrounds, with high levels of knowledge and skills.

- Belonging: All students have a strong sense and appreciation of their own culture and heritage, as well as of those of their diverse classmates.

- Commitment to dismantling racism and oppression: All students understand the role that institutional racism and other forms of oppression play in our society and have the skills, vision, and courage to dismantle them.

- Diversity: All students appreciate and value different perspectives, thoughts, and people and have friendships and collaborative working relationships with students and adults from different racial and economic backgrounds.

The ABCDs align closely with what other scholars have developed (see, e.g. john a. powell). At RIDES, they have become a useful tool for starting discussions among parents, educators, and students about desired outcomes for students, for assessing the current status of their school approach (see the RIDES Progress Assessment), and for organizing more than 150 practices and examples that sites can use in moving toward integration.

There is a predictable and common set of challenges schools, districts, and CMOs face in moving beyond desegregation. When educators try to move to true integration, they typically face four kinds of challenges in their work. Not everyone in a particular setting may be stuck at the same point, but the sentiments expressed below create real obstacles to improvement:

- We are diverse and we don’t see the inequity in our schools, districts, or charter management organizations (CMOs);

- We see the inequities, and there are so many of them, we don’t know where to start;

- We are ready to work to move toward true integration, but don’t know how to work together well, especially on racially charged topics;

- We are taking steps toward integration and have put some initiatives in place, but we are disappointed when we don’t find the silver bullet that solves the problem.

Recognizing these challenges has enabled RIDES to develop a set of tools and processes that helps sites start to address them. They begin by bringing together a diverse team to develop a personal and team equity culture that includes creation of common definitions of equity and integration, relational trust, and exploration of their individual and collective biases. This is prerequisite and continuing work that sites do as part of the RIDES Equity Improvement Cycle, a six-step approach to tackle specific equity focus areas that the sites identify. It is currently in use in 25 schools in eight states and the District of Columbia and in several large systems, including New York City.

Students are underutilized and potentially powerful partners in equity and integration work. Most efforts to increase equity and integration in schools treat students as subjects of improvement efforts designed and implemented by adults. Even though they are most affected, students are often disengaged, passive recipients of work the adults undertake. We have been disrupting that paradigm and systematically including students as partners with adults in equity improvement work. Over the last several years, high schools in New York, Illinois, and Iowa have used a version the RIDES Equity Improvement Cycle, cumulatively engaging more than 100 students, of whom the majority were students of color, working side by side with majority white staff. Engaging students in this way has had a profound impact on both students and educators in all three schools. Students report that “It was the first time I ever felt listened to by adults in this school,” and “I didn’t know the teachers really care.” Teachers describe student voice as “essential to the process,” with many of the white teachers saying things like “the students noticed things that I didn’t notice in the classrooms,” and “their interpretation of what we saw was just so different than mine.” Teachers of color found that students were able to voice issues they faced every day. Follow-up plans for improvement proposed and implemented in these schools have broader ownership and are more targeted to the real needs and opportunities for students than in the schools where students are not part of the integration process.

Beyond “diversity at the door”: Creating truly integrated school communities

While the data from the D.C. Policy Center’s recent report illuminates shifting demographics, both RIDES and Kindred are finding that the way those changes impact school dynamics matters for families and outcomes for children. As former U.S. Secretary of Education and current CEO of The Education Trust John King shared, “Diversity at the door is not sufficient to create equitable environments… The plan has to go beyond just moving students around. It has to include how to create functional diverse communities. That means parents have to talk across difference… Otherwise we risk people walking away either congratulating themselves for change that isn’t real or people throwing up their hands saying diversity doesn’t work.” To advance equity and create schools that meet the ABCDs and live up to the full potential of integration, we must address the deeply socialized beliefs that created and maintain segregation. As one Kindred parent recently said, “We either do this work now or my children will have to do it. I don’t want to pass it to the next generation.”

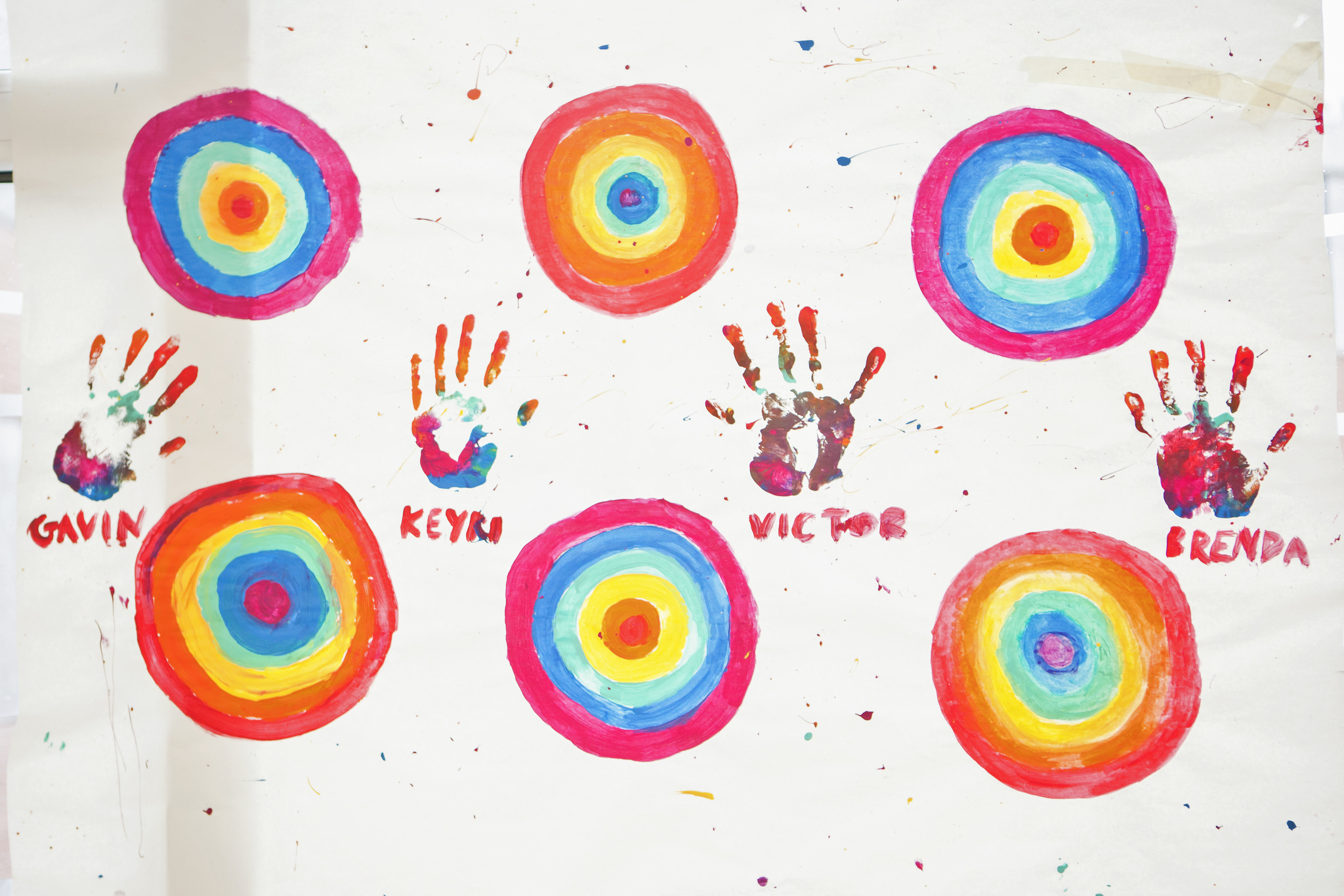

Feature photo courtesy of the DC Public Charter School Board (Source), used with permission.

Laura Wilson Phelan is Founder and Executive Director at Kindred. For over 20 years, Laura has led social change efforts at grassroots and management levels across the nonprofit and government sectors, including most recently as an elected representative to the DC State Board of Education. Laura’s career began as a bilingual middle school teacher with Teach For America, after which she served in the Peace Corps. Laura earned a Master in Public Policy from the Harvard Kennedy School and a Bachelor of Arts in politics from Wake Forest University. She is the proud mother of twin third-graders. Twitter: @lwilsonphlean @kindred_dc

Lee Teitel is the founding director of Reimagining Integration: The Diverse and Equitable Schools (RIDES) Project at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. RIDES supports schools, districts, and charter organizations in moving beyond desegregation (getting diverse students in their buildings) to become places where all children learn at high levels, feel included, appreciate their own and other cultures, understand racism, and work to dismantle it. Through RIDES and as an individual consultant, Teitel has worked with dozens of schools and districts to test and develop impactful ways of creating and sustaining diverse, equitable, and integrated schools.

Notes

[1] Putnam, Robert. (2015). Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis. Simon & Schuster: New York, p. 210.

[2] McNamara Horvat, E., el. al, (2003). Social Ties to Social Capital: Class Differences in the Relations between Schools and Parent Networks. American Educational Research Journal, 40(2) 319-51.