This excerpt has been adapted from Black Food Geographies: Race, Self-Reliance, and Food Access in Washington, D.C. (UNC Press, April 2019). In this book, Ashanté M. Reese makes clear the structural forces that determine food access in urban areas, highlighting Black residents’ navigation of and resistance to unequal food distribution systems. Linking these local food issues to the national problem of systemic racism, Reese examines the history of the majority-Black Deanwood neighborhood of Washington, D.C.

Based on extensive ethnographic fieldwork, Reese not only documents racism and residential segregation in the nation’s capital but also tracks the ways transnational food corporations have shaped food availability. By connecting community members’ stories to the larger issues of racism and gentrification, Reese shows there are hundreds of Deanwoods across the country.

Reese’s geographies of self-reliance offer an alternative to models that depict Black residents as lacking agency, demonstrating how an ethnographically grounded study can locate and amplify nuances in how Black life unfolds within the context of unequal food access. Image: uncpress.org

The early makings of a self-reliant community

What is now known as Deanwood was once farmland worked by enslaved Black people. Ninian Beall, a white farmer, initially acquired it as part of a land grant in 1703.[1] Ownership changed hands multiple times, but by 1833 Levi Sheriff, another white farmer, purchased it. When he died, Sheriff’s three daughters subdivided the land in 1871 after realizing that the decline the family farm underwent during the Civil War was likely irreversible.[2]

When the sisters developed these subdivisions, it is likely they assumed that white families would be attracted to the newly built homes, the expansive landscape, and the railway that ran through Deanwood from Bladensburg, Maryland, to a Potomac River wharf. By 1873, however, only two plots of land had sold, for a total of $50.[3] In 1874, the next buyer purchased one of the subdivisions, offering the sisters two plots in the city center in exchange. Reverend John H. W. Burley, who purchased the subdivision, was the first African American on record to purchase land in the Deanwood area, setting a precedent for Black landownership in the community.

Archival records between 1874 and the turn of the 20th century are unclear concerning how African Americans heard of Deanwood or why they chose to move there. It is likely that word of mouth traveled routes similar to those followed by the people who made up what we call the Great Migration—throngs of Black people looking for opportunities in urban centers around the country. What is clear, however, is that Black residents established institutions that were key to community sustainability. Between 1880 and 1886, residents built Contee African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and the Burrville School, the first to serve African American students in the greater Deanwood community. In 1909, Nannie Helen Burroughs opened the National Training School for Women and Girls.[4] […] By 1926, at least six additional churches were built, several along the main thoroughfare that would later be named Sheriff Road after one of the white slaveholding farmers who originally owned land where Deanwood sits.

Photo credit: Juan Pineda / @criomatic_designs

The mass exodus of African Americans from southern cities during the Great Migration left its mark on D.C. generally and Deanwood specifically. In 1920, Washington, D.C.’s Black population was 110,000.[5] Ten years later, that number had grown to 132,000, with a great majority of new Washingtonians hailing from Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, where the agricultural system had begun to decline after World War I.[6] These migration trends were consistent in Deanwood. Among the residents included in an oral history project conducted by D.C. historian Ruth Ann Overbeck, eight out of 20 participants or their families had migrated to Deanwood from other southern states such as Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Others moved there from other parts of the city and did not detail if they had origins elsewhere.[7]

Their reasons for choosing Deanwood varied. Some families sought Deanwood at the encouragement of friends or relatives who already lived there. Others came in search of educational opportunities for their children and thought Deanwood would provide a better environment. Still others were seeking more progressive racial and economic climates than what they experienced in their home states. Though migrants could not escape the anti-Blackness that created little or no access to schooling and a sharecropping system in the South that amounted to another form of bondage, urban centers like Washington, D.C.—combined with the talents they brought with them—gave them hope for creating better futures for themselves and their children.

* * *

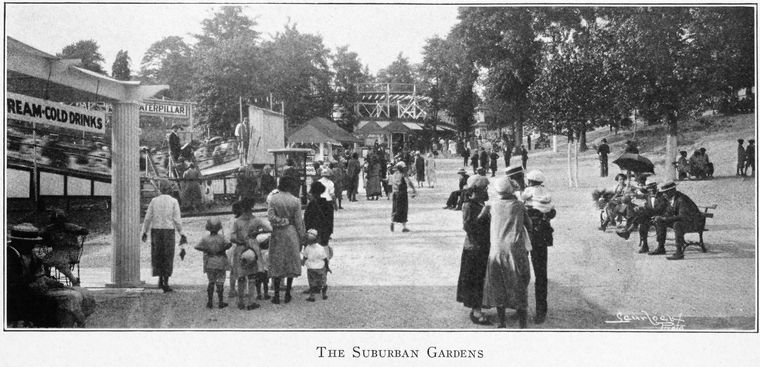

In D.C., communities that formed reflected Black people’s commitments to surviving in spite of white supremacy. Compared to a neighborhood like Shaw, which had emerged as a center of Black culture and intellectual life in D.C.,[8] Deanwood seemed like the backwoods. Established by freedmen on the outskirts of Washington City in the nineteenth century, Shaw was home to several prominent African Americans and to some of the most prestigious African American institutions: Howard University, the Whitlaw Hotel, Industrial Savings Bank, and Freedmen’s Hospital.[9] Though it had the only amusement park for Black residents in the early twentieth century and was well connected to railways, Deanwood neither looked nor felt as developed as its counterpart.

Above: Deanwood’s Suburban Gardens amusement park. Photo by William Henry Jones, Scurlock Studio (1927). From The New York Public Library (Source) |

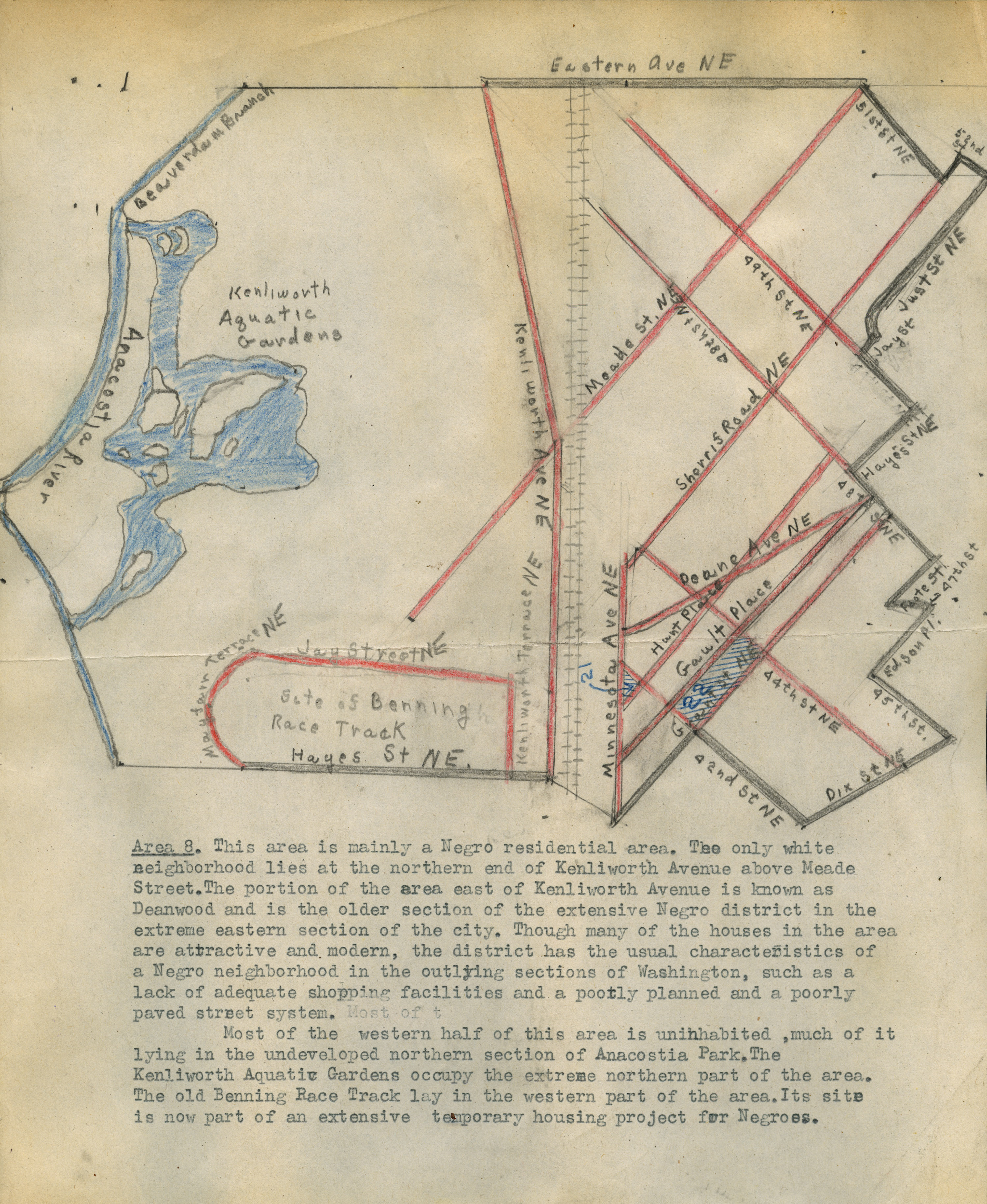

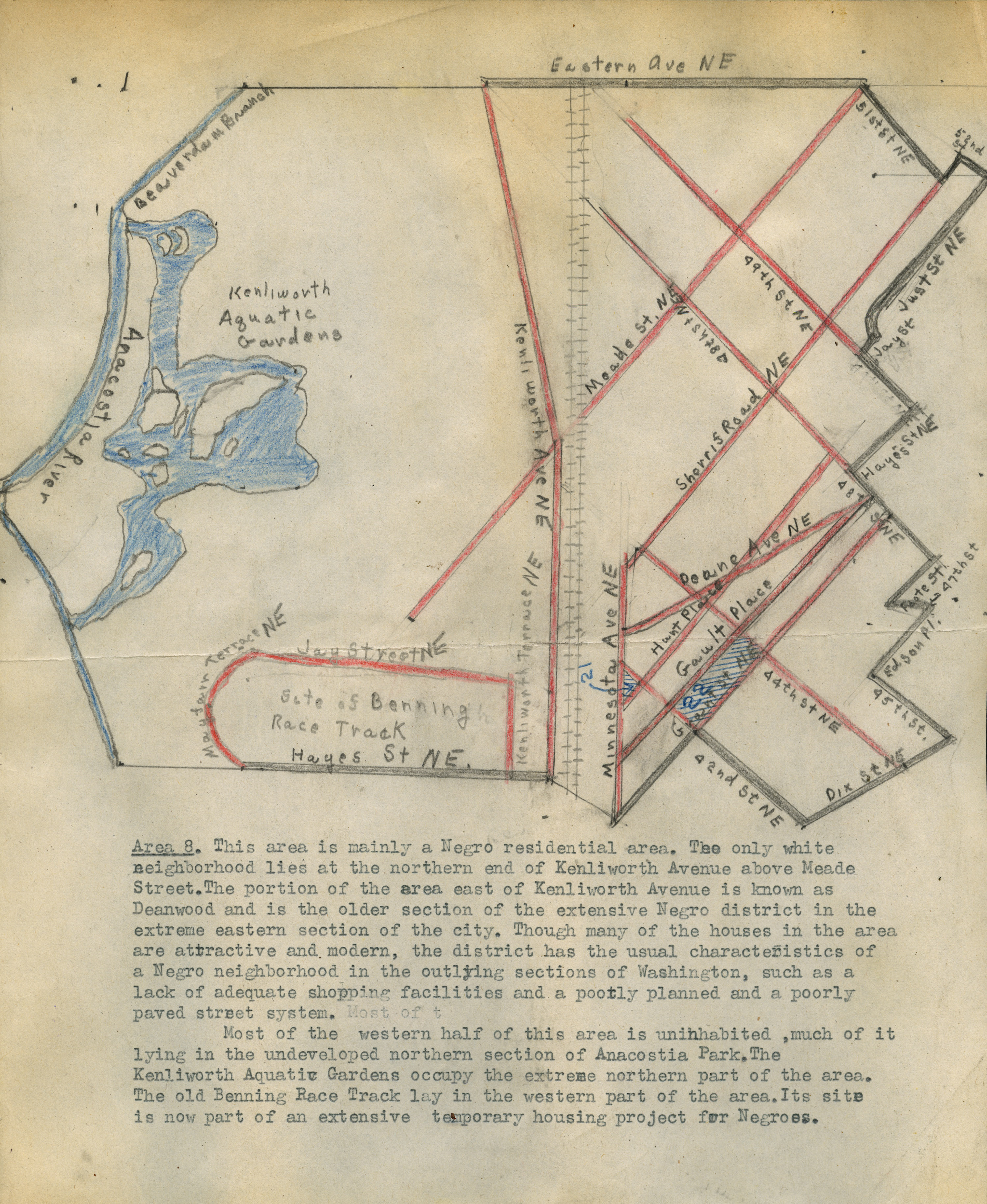

Deanwood, east of the Anacostia River, was considered by other Washingtonians as distinct from “the city” of Washington because of its relative physical and social isolation from the African American epicenters.[10] City services were slower. Roads were not paved until well into the 1950s, and even then, some residents still did not have indoor plumbing. A hand-drawn map from 1948 (below) described Deanwood as “mainly a Negro residential area” that, in spite of nicely kept homes, displayed “the usual characteristics of a Negro neighborhood in the outlying sections of Washington, such as a lack of adequate shopping facilities and a poorly planned and poorly paved street system.”[11] The map and the language used to describe the area illustrate the racial segregation that, by the time the map was drawn, was an expected and normal part of residential—and to some extent commercial—life for those who lived in Deanwood.

John P. Wymer’s hand-drawn map of Deanwood in 1948. WY 0397M.08, John P. Wymer Photograph Collection, Historical Society of Washington, D.C. |

Yet, it should not be assumed that people were less industrious than their counterparts in parts of D.C. that had better infrastructure. Indeed, they were creating community and making lives. The combination of people who settled there—migrants from the South, skilled craftsmen, and entrepreneurs—worked to create a community that met most of residents’ needs, despite the challenges presented by racism, physical isolation, and vastly undeveloped tracts of land.

Growing food in Deanwood

Owning land and homes provided the space for farming and gardening, which were integral to the growth and development of Deanwood in the first half of the twentieth century. For example, Vincent Bunch reported that around 1923, his parents sold the land they owned in South Carolina, packed up their lives, and moved to the nation’s capital. Although they had owned their land in South Carolina, they were still hoping D.C. was a great place to raise children, to make more money, and to not have to farm. Vincent’s father had been an industrial education teacher after he finished college but sought other employment when they moved to D.C., because “back in those days Pullman [porters] seem[ed] like they made a little bit more money. He could make more money being a Pullman than he could teaching school in little southern schools.”[12] When they arrived, Vincent’s parents and their firstborn son lived with family until they were able to purchase the materials needed to build their home in Deanwood. […]

Within two years of arriving in Washington, D.C., the family’s home was finished, and they welcomed another son, Vincent, who would later be interviewed about living and shopping in Deanwood in its early formation as a Black enclave.

Many early Deanwood residents like Vincent’s parents had complex relationships with the Deep South and farming. On one hand, they left in search of something better than lifelong farming, which often had to be supplemented with other work. For those who migrated from states in the Deep South in particular, farming was emblematic of the continued subjugation of African Americans who were unfairly cheated out of money, their labor, or produce. On the other hand, the skills they learned as farmers were used to cultivate a multifaceted foodscape in Deanwood that included gardens, small farms, and independently owned general stores that primarily sold dry goods, some freshly slaughtered meats, and household items needed to meet daily needs. Despite the pull away from the Deep South and the Black agrarianism that largely built its economy, the same skills that were associated with subjugation were used as liberation tools, as early residents used them to develop individual and communal self-sufficiency.

Vincent was interviewed in 1987 about life in Deanwood in the 1930s and 1940s. At the time of his interview, he was a 62-year-old married Deanwood resident who had recently retired from the Interior Department, where he had worked as a cartographer. In his interview, he reflected on several aspects of the food environment, which included the strategies his parents employed to meet their food needs:[13]

See my father bought six lots. The house set on two lots, there were two on this side of the house and two on the other side! And two of the lots are still there. We planted everything … uh corn, sweet potatoes, uh peanuts, greens and stuff like that. Squash, peppers and tomatoes. We had seven peach trees, two apple trees and one plum tree that didn’t bear too much … and a cherry tree. And there was a pecan tree. The pecan tree is still there … years back when my mother brought that tree up, she brought it up from South Carolina, and we planted it. We could get … I’d say maybe from two or three shoeboxes full! Now the squirrels came in and got them. Come to think about it, we were pretty self-sufficient … our food needs.

Above all else, owning land was the basis on which Vincent’s parents planned not only where they would live, but also what they would eat. Working the land became part of everyday practice as residents used food production as a means to both resist the subjugation associated with the Deep South and to plant roots that connected their D.C. experiences with their former homes. […] The South showed up in their gardens, in their stores, and in the self-reliance strategies they cultivated to created new lives in Deanwood.

Selling produce from homes or carts and wagons was part of Deanwood’s local economy until the early 1950s. Julia Parks noted, “Mothers were reported to have prepared and marketed foodstuffs from their homes until licensing became a requirement. At least two fathers of the respondents were remembered as selling their produce from carts within the community, out of their homes, and at the Florida Ave. Market as well.”[14] Those fathers were known by most as hucksters. Though many of the early residents were educated, growing and selling food was one way to either make a living or supplement their income. Individual-level economies—as represented by the hucksters—were supported by community buy-in and support.[15]

* * *

Allison, a 68-year-old Deanwood resident, remembered her family’s engagement with the hucksters, joking that she had forgotten about them, probably because her ex-boyfriend from her younger days was a huckster who came through the neighborhood selling whiting from boxes. When he would come down their street selling fish, her mother would say, “There goes your huckster,” as she tried to avoid him. She recalled: “They would come through on the wagons. They would bring fish here. They brought vegetables, watermelon … I mean, especially before the Safeway and of course, when the Safeway came through that sort of cut into their … But yeah, I had forgot about the hucksters … The vendors who would come through with their horses … yeah I know all about the hucksters. Yeah, the vendors that would come through with their horses and eventually, I think, there probably were trucks that came through.”

Allison illustrates both the business and the interpersonal aspects of the practice. Supporting local businesses not only supplemented individual families’ food production, but also reinforced the belief that self-reliance was as much about communal survival as it was about individual gain.[16] Her narrative also foreshadows forces that disrupted self-reliance: corporate growth in food production and perceived modernity. […] Supermarkets challenged community-based practices such as huckstering. The convenience and variety offered by these larger stores created a food environment in which hucksters could not compete. Though supermarkets were only just beginning to gain traction in the 1940s and 1950s as the preferred venue for obtaining groceries, early evidence of the damage they caused in neighborhoods—and by extension in social relationships—is present in Allison’s narrative.

* * *

Small grocers

In addition to producing food for family consumption and selling it, other entrepreneurial pursuits were a foundational component of Deanwood’s early development. Though many African Americans in D.C. were able to obtain government employment, many others explored entrepreneurship in their segregated neighborhoods. It provided an opportunity for African American business owners to both serve their neighborhoods and resist racist structures that constrained physical, economic, and social mobility. The capital generated contributed to the economic and social vitality of these neighborhoods.[17] Residents in Deanwood were no different. Overbeck and colleagues noted that Black businesses were the crux of community economic development in Deanwood:[18]

Between 1907 and 1945, Deanwood had a wide variety and number of small businesses owned and operated by black persons. About a dozen types of businesses were reported. These included small groceries, pharmacies, coal and ice services, a shoe repair, eating and food services, a combined real estate and grocery, funeral parlors, a materials transport business and bus service, cleaners and an oil company. In addition, large scale and small scale building and building related crafts were carried out commercially … Crafts such as electrical, plumbing, cement finishing and stone making were typically carried out as both a business and as community activity.

Overbeck’s analysis suggests that the self-reliance ethos that undergirded much of Deanwood’s development was as much about community-building and community success as it was about individuals’ thriving. Steven Gregory illustrated that community-building and community success were central to the development of predominantly Black communities, if for no other reason than that equal protection under the law was not a reality. The political power, social networks, and skills that were shared were invaluable in terms of creating a thriving neighborhood.[19]

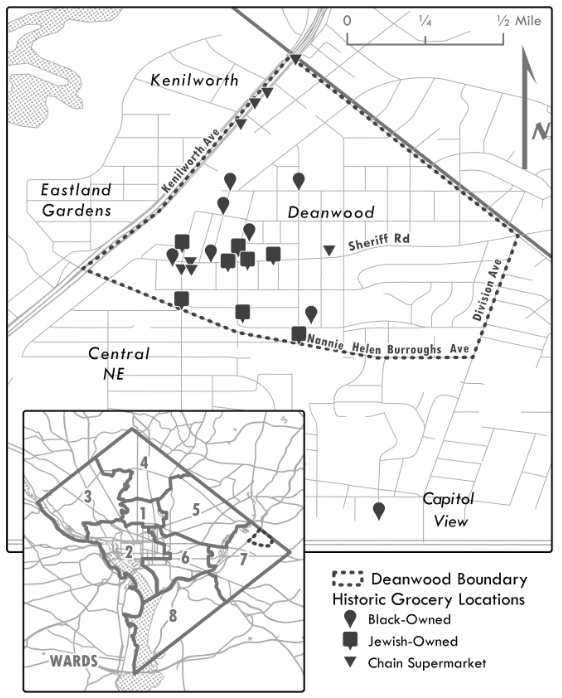

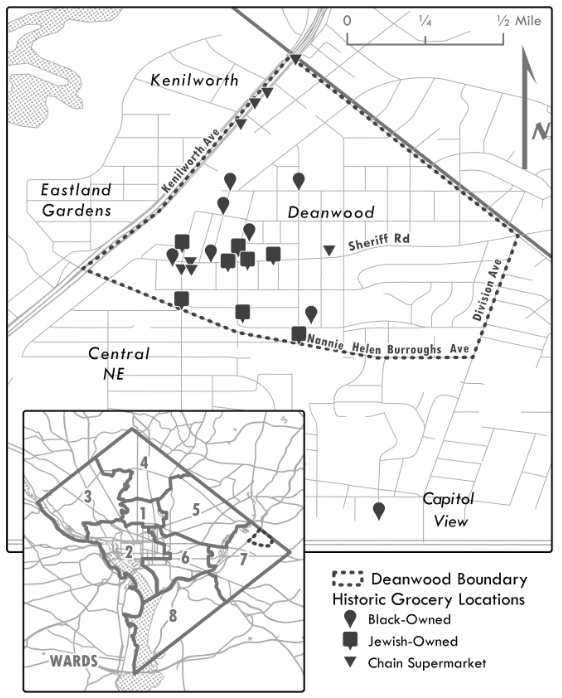

Some of the earliest stores between 1900 and 1930 were food stores, which supplemented individual families’ food production. In her description of Black-owned businesses, Parks noted, “It is likely that food stores emerged first and in connection with individuals selling surplus food stuffs raised on small ‘farm type land.’”[20] There was, however, a disconnect between Black-owned food stores (below) and what residents described as central to their shopping practices. Seven Black-owned food stores were identified during the interviews with Overbeck, but none of the 20 respondents included any commentary on shopping at these stores for their daily food needs. Respondents’ explicit commentary about Black-owned food stores was scant. Instead, Jewish-owned and -operated stores were a central theme in their oral histories.[21],[22] […]

Grocery stores operating in Deanwood between 1925 and 1960. This map was created based on stores that were reported in the Overbeck oral history interviews and those collected in an online database called Groceteria. Map courtesy of Emeline Renz (@mapgrrl). |

Respondents in Overbeck’s oral history of Deanwood identified eight Jewish-owned grocery stores, many of which were part of the District Grocery Store (DGS) cooperative. Begun in 1922 by twelve Jewish store owners who pooled their resources to buy directly from manufacturers, DGS comprised over 300 stores in the Washington, D.C., area at its peak.[23] In a 1963 article in the Washington Post titled “Small Stores Thrive through Cooperation,” William Raspberry quoted Henry Noon, then president of the DGS collective: “Our wholesale operation is a terrific thing for small merchants … because of our volume buying and our connection with Eastern Retail Grocers (a division of Cooperative Food Distributors of America) we are able to keep our wholesale prices so low that our merchants can often undersell the chains on such perishables as meats and produce.”[24] Collective buying power yielded greater products at better prices, which resulted in consistent, repeat clientele for DGS stores in Deanwood and a distinctiveness from Black-owned grocery stores.

* * *

Transitioning to supermarkets: The makings of the grocery gap in Washington, D.C.

Gardens, small farms, and neighborhood grocers may have characterized the early twentieth century, but it is the supermarket that emerged as the quintessential component of the national and local food system, so much so that narratives around fixing broken food systems often begin with the supermarket—not the ways people historically created local foodways. In the 1930s, the largest grocery stores averaged between 6,000 and 8,000 square feet. By the 1960s, supermarkets were as large as 60,000 to 80,000 square feet.[25]

The structural changes that accompanied supermarkets have had lasting effects on national and local levels. Even though Henry Noon boasted that the DGS was thriving as late as 1963, the cooperative dissolved about 10 years later. In a 1971 Washington Post article, reporter William H. Jones wrote: “District Grocery Stores Inc., a cooperative venture of Washington merchants for nearly 52 years, has begun to liquidate its business—heralding the end of an era when so-called mom and pop stores dotted every neighborhood and thrived on the convenience offered nearby residents. Although DGS was able to survive the Great Depression and even to grow during the formative years of the great supermarket chains, it suffered immensely from the 1968 rioting in the city and finally was killed last summer when supermarkets began late night and Sunday hours.”[26]

* * *

The built environment in Washington, D.C., drastically changed post-1968, particularly in terms of grocery store access. By 1971, supermarkets reduced their stores by 24 percent. As William H. Jones noted in a 1971 article in the Washington Post cited earlier, supermarkets followed a national trend, choosing to leave predominantly Black inner-city neighborhoods in favor of more affluent, white suburban areas. By 1982, the number of major grocery stores had fallen to 33, down from 91 in 1968.[27]

Although Safeway initially maintained 61 stores in the District, 45 of them in Black neighborhoods in 1971, that number dwindled to 31 by 1978. Between 1978 and 1981, Safeway reduced the number of stores in the District from 31 to 25,[28] contradicting strong remarks the company’s representatives made about the importance of maintaining grocery stores in inner cities to meet the basic needs of residents.[29] In 1980, the Safeway in Deanwood closed. A spokesperson remarked that the company closed the store because it had been “unprofitable for some time.”[30] […] Perhaps predictably, supermarkets followed wealthy and white people, many of whom left the city in favor of suburban areas.

* * *

In the midst of supermarkets closing stores in predominantly Black neighborhoods, executives from Safeway and Giant mentored Black entrepreneurs who wanted to open grocery stores.[31] Super Pride, a Black-owned grocery chain, opened in 1981 in the building Safeway had previously occupied in Deanwood. Super Pride was part of Community Foods, a Baltimore-based chain of Black-owned grocery stores. At the time it opened its first and only store in D.C., Community Foods had operated in Baltimore for 11 years and maintained six stores. The chain’s founder, Charles T. Burns, received part of his training in grocery store management from Safeway, the largest grocery chain in the country. Neither Burns nor the store manager had any known intimate ties to businesses or families in Deanwood. However, they specialized in serving inner-city communities and positioned Super Pride as an opportunity to provide both food and jobs in a neighborhood reeling from a mass exodus of middle-class residents.[32] Super Pride attempted to fill many—perhaps too many—gaps: a gap in food access, a gap in employment, and a gap in the economic sustainability in the neighborhood. Super Pride was not alone. George Shelton, who “defied skeptics who said a black-owned supermarket couldn’t make it on Capitol Hill,” opened a second store in 1980, predating Super Pride.[33] […]

Black entrepreneurs similarly opened groceries in Buffalo, New York[34]; Columbus, Ohio[35]; and Richmond, Virginia[36] in predominantly Black neighborhoods that struggled with food security. All opened with a similar goal. Black entrepreneurs used market-based skills, attempting to fill a need for communities they presumably had a connection to, even if that connection was only racial identity.

* * *

Both Safeway and Super Pride were invested in and reified the notion that Black-owned businesses were solutions and saviors in Black neighborhoods. However, integration, increased access to other parts of the city, brand loyalty, and movement to the suburbs in part altered the meanings of Black neighborhoods and what it meant to support Black-owned businesses. Super Pride closed its doors in Deanwood, and its parent company closed three stores in Baltimore in June 2000.[37] Three months later, the company decided to close all its remaining stores.

In an interview with the Baltimore Business Journal, Super Pride’s president, Oscar A. Smith Jr., said that population decline was one of the reasons the store had not been able to stay open—“the same stores are fighting for fewer dollars.”[38] Being a small, independent company, Super Pride could not absorb those losses, and while small companies like it were drowning, corporations like Giant and Safeway selectively maintained stores in parts of the city.

* * *

Conclusion: Industrialization and the destabilization of Deanwood’s local foodscape

The industrialization of food production and distribution in the United States altered the national foodscape and Deanwood’s local foodscape. Local food producers and sellers—like hucksters, the mothers who sold their food products from home, and the small grocers on nearly every street—were casualties in a shift toward the convenience of larger, better-stocked stores. As the nation’s food system became more industrialized and usurped by the market economy, residents became more dependent on supermarkets, unknowingly contributing to the destabilization of Deanwood’s local foodscape. Without the local food practices upon which Deanwood’s food security was partially based, the neighborhood’s food access was at the mercy of the increasingly transnational food corporations that systematically left Black neighborhoods in favor of the suburbs. All these changes in food access were embedded in, not separate from, national trends in racial segregation and inequalities that shaped access to resources and opportunities. Within this context, Black entrepreneurship in the form of small stores in the first half of the twentieth century, as well as supermarket chains like Super Pride in the 1980s, reflected how important entrepreneurship was to addressing food inequalities that Black residents did not create.

* * *

Adapted from BLACK FOOD GEOGRAPHIES: RACE, SELF-RELIANCE, AND FOOD ACCESS IN WASHINGTON, D.C. by Ashanté M. Reese. Copyright © 2019 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher, uncpress.org

This excerpt has been adapted and condensed with permission. Condensed material is indicated with […] or * * *.