In mid-March, the United States Census Bureau released data on the components of population change for metropolitan areas in the United States. The data show that the D.C. metro area’s population grew at a rate of 6 per 1,000 people between July 2022 and July 2023. Compared to other higher-cost metro areas,[1] [MOU1] the D.C. metro area fared second best—only behind the Miami metro area, which grew at a rate of 7 per 1,000 people. Natural change (births minus deaths), and to a lesser degree, international migration fueled the population growth of the D.C. metro area. During the period in question, higher-cost metro areas had an average population growth rate of fewer than 1 per 1,000 people.

Lower-cost metro areas fared much better. They had an average population growth rate of 14 per 1,000 people. The Austin metro area grew the fastest of the metro areas listed—growing at a rate of 21 per 1,000 people. In other words, between 2022 and 2023, for every 1,000 people living in the Austin metro area, its population increased by 21 people.

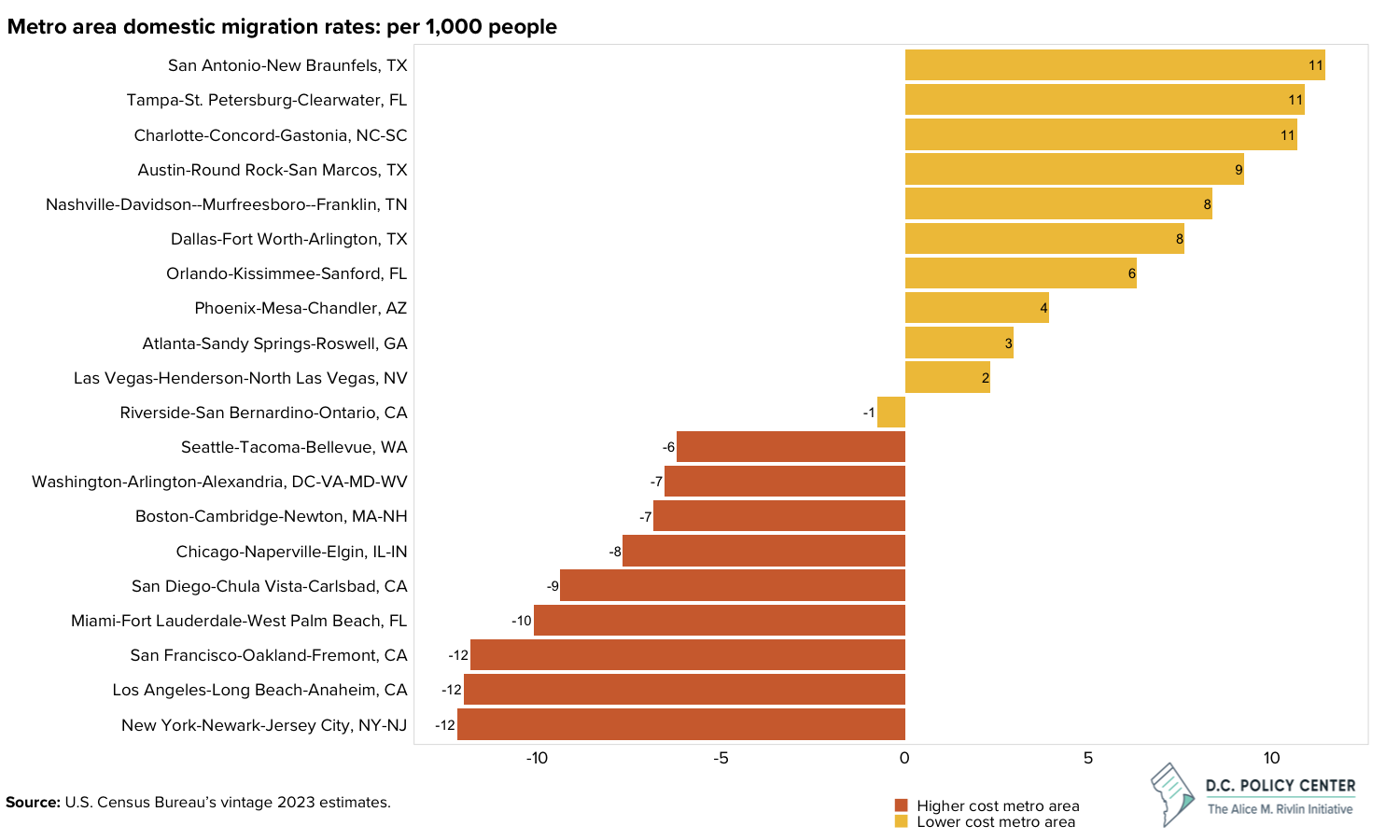

The stronger performance of lower-cost metro areas was starkest with respect to domestic migration. As the chart above shows, between 2022 and 2023, with a single exception, lower-cost metro areas had more people moving in than moving out, while higher-cost metro areas had more people moving out than moving in. Over the course of the year, lower-cost metro areas had an average domestic in-migration rate of almost 7 per 1,000 people, while higher-cost metro areas had an average domestic out-migration rate of 9 per 1,000 people.

Compared to the other higher-cost metro areas listed, the D.C. metro area did slightly better than average. The D.C. metro area had a domestic out-migration rate of 7 per 1,000 people. Put another way, for every 1,000 people living in the D.C. metro area, 7 people moved out. Meanwhile, lower-cost metro areas—such as Austin and San Antonio—had domestic in-migration rates of 9 per 1,000 people, and 11 per 1,000 people, respectively.

These domestic migration patterns are not new. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many higher-cost metro areas—including the D.C. metro area—experienced population declines—with domestic out-migration being an important contributor. At the same time, many lower-cost metro areas witnessed strong domestic in-migration. A variety of forces likely underlie these patterns, including the cost of living, job market conditions, the ability to work remotely, and peoples’ lifestyle preferences.

In sum, the recent population and migration data suggest that higher-cost metro areas—such as D.C.—cannot take their residents for granted. It will be crucial for higher-cost metro areas to pursue policies that reduce the cost of living—such as increasing the supply of housing. It will also be critical that higher-cost metro areas make investments that improve the quality of life—such as supporting and funding high-quality city services. By pursuing such policies, higher-cost metro areas can take steps toward re-establishing their competitive edge.

[1] This piece divides higher- and lower- cost metro areas based on Bailey McConnell, “What do migration and labor force trends tell us about D.C. and other large, high-cost metro areas?” D.C. Policy Center, October 5, 2022. McConnell was influenced by Stephen Whitaker, “Migrants from High-Cost, Large Metro Areas during the COVID-19 Pandemic, Their Destinations, and How Many Could Follow,” March 25, 2021, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.