During the COVID-19 pandemic, households with children are more likely to face loss of employment income than households without children nationwide. This is likely due to parents having to give up jobs or reduce their hours to shoulder the additional responsibilities of educating and caring for their children without outside help. Until child care facilities and schools fully reopen, 17.5 million workers, 11 percent of the U.S. workforce, will be unlikely to return to work full-time, having to take care of young children. As D.C. progresses through its reopening phases, economic recovery will in part depend on ensuring child care access and availability.

Whether child care services will be available, however, remains uncertain. In mid-May of 2020, 88 percent of all child care facilities in D.C. reported being closed, many relying on insufficient government subsidies and family payments to cover utility costs and payroll. Facilities that remained open haven’t fared much better, with 71 percent of open facilities operating at less than 25 percent capacity. The industry had been operating on narrow profit margins prior to the pandemic, with many workers making near minimum wage and qualifying for public assistance.

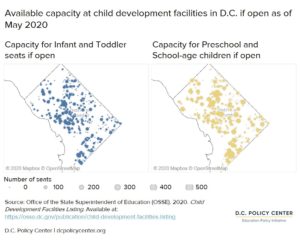

Now due to pandemic-related financial pressures, 20 percent of child care slots could be lost in the District, a city with an already limited child care supply where the capacity for infants and toddlers represents about 28 percent of this population. These child development facilities are located throughout the city, with some of the largest centers located downtown where some parents commute to work, affecting residents in every Ward. The map below shows potential capacity without limitations and closures caused by the pandemic.

With facilities at risk of closing permanently, many child care workers, largely women and people of color in D.C., would be left without jobs. In May, 14 percent of D.C. child care providers reported needing to lay off or furlough their workers, or reported being laid off or furloughed themselves. Fifty percent of D.C. child care providers anticipated such actions in the next four weeks. For child care workers at facilities beginning to reopen, returning to work may not be possible; the work environment presents high risks to physical health and safety.

In D.C., 60 percent of child care providers reported concerns about insufficient revenue, and in many cases, the financial difficulties that child care providers are currently facing are not solved by relief funding. Only 25 percent of child care businesses nationwide are receiving Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans. In D.C., 20 percent of child care providers reported logistical challenges when applying for loans to help retain their workforce. While the District continued subsidy payments to operators based on enrollment, and in May, revised their guidelines for operators to receive their average monthly subsidy payments, many centers must still rely on families paying out of pocket. With less than 25 percent of families currently paying tuition, child care centers are left with drastically reduced revenues.

Reopening guidelines outline new restrictions and protocols for child care centers due to coronavirus concerns.[1] In addition to financial hardship, restrictions on capacity and increased sanitation[2] create additional hurdles for child care centers. Reopening guidelines limit the number of child care seats, hurting revenues and sustainability, and preventing parents from returning to work in reopening phases, a problem seen in Maryland. Child care facilities will also have to incur additional sanitation costs, further hurting their ability to stay afloat. Without proper financial support, reopening under these conditions may not be possible for child care facilities, disproportionately affecting small businesses, parents, women, and people of color in D.C.

To learn more about how child care facilities are approaching these issues, the D.C. Policy Center reached out to several stakeholders to ask the following question: What is the most important factor impacting the sustainability of child development centers?

Ruqiyyah Anbar-Shaheen, Director of Early Childhood Policy and Programs, DC Action for Children

And those looking to reopen need help as they are facing enormous expenses to comply with health and safety guidelines, from reduced class sizes to barrier walls to enhanced cleaning schedules to increased staffing needs.

Early care and education are essential, but child development centers and family child care homes have always been relegated to the margins of our education system, leaving many providers without the support, infrastructure, and funds to weather financial rainy days. COVID-19 has been a financial hurricane for many providers: nearly all of the providers we surveyed described having financial concerns as a result of COVID-19, and national estimates show that the District could be at risk of losing up to 20 percent of child care providers.

For now and in the months to come, child care providers need business-sustaining emergency funding to help make ends meet, whether they have determined that it’s safe to reopen or not. And those looking to reopen need help as they are facing enormous expenses to comply with health and safety guidelines, from reduced class sizes to barrier walls to enhanced cleaning schedules to increased staffing needs. Public financial support for these essential businesses has been insufficient to date and is needed to keep child care programs whole as the impact of COVID-19 continues.

In the long run, we need to treat early care and education with the same level of importance as P-12 education. From our perspective, the child care subsidy program is the right vehicle for strengthening the sector, and it needs some key enhancements to best support providers. Programs need stability in subsidy payments through enrollment-based reimbursements that do not require in-person presence (rather than the current attendance-based model), equitable support in meeting quality standards, and more widespread and enhanced systems of shared services to reduce their administrative burden and allow them to focus on delivering quality care and education for young children. This also means fair wages for early educators to attract and retain skilled professionals. As a society, we have a long history – rooted in race and gender-based discrimination – of undervaluing the skills needed and the essential nature of caring for and educating infants and toddlers. But as D.C. starts out on the path to an economic recovery, it’s more clear than ever that these programs are key to early childhood development, to families’ economic stability, and to a healthy economy.

Kamren Rollins, Interim CEO, Sunshine Early Learning Center

Child development centers have significantly more challenges sustaining and providing high-quality child care to children due to COVID-19, especially those coming from underserved communities.

The most important factor impacting the sustainability of child development centers are funding and our ability to engage consistently with children and families. In general, child development centers operate on extremely tight financial margins, but the impact of COVID-19 has put many programs at extreme risk of permanently closing. Gratefully, through the resources that we have been able to establish over the years, we have been able to pay our staff and buy the needed safety and cleaning equipment, but that is not the case for many organizations. Child development providers must purchase a plethora of new items and materials to ensure we continue to provide the safest environment for children, staff, and families; this task is especially more difficult without additional resources and funding.

With that said, child development centers face an added challenge attempting to serve our children and families as effectively as we had before the impact of COVID-19. We now have significant reductions in the number of children we are able to serve due to the regulations regarding group size and social distancing. The reductions in group size have caused many child development programs to greatly reduce the number of children they allow into the center each day. This means that a great number of children miss out on the daily developmental activities and interactions they once were so accustomed to experiencing.

This creates additional barriers for child development centers, like Sunshine Early Learning Center, that serves a community that is predominantly underserved because now the direct interaction we have with the children and families we serve is limited. It is also important to note that the technological access that may be in abundance for children that come from affluent households is not the same for all children, creating additional limitations in our ability to continuously communicate with children. Child development centers have significantly more challenges sustaining and providing high-quality child care to children due to COVID-19, especially those coming from underserved communities.

Katrice Fuller-Whitaker, Ward 6 PAVE Parent Leader

This pandemic has shown us that many of our families east of the river are essential or frontline workers, needing not only open childcare centers, but centers that could accommodate the hours needed for them to work.

Just look at that face…how could you NOT do anything within your power to ensure the best for that face? How could you NOT want him to have equitable access to childcare during one of the most unprecedented times in America? There are many lingering thoughts as the city considers plans to reopen; many of these plans are surrounding childcare.

Prior to the pandemic, the amount of affordable and equitable childcare centers in the District was scarce. This scarcity led my family to attain childcare in Maryland. The D.C. Early Childcare Education (ECE) sector was constantly negotiating for more funding and more programming, especially in those wards struck with high unemployment, unstable housing and poverty rates. It has already been proven that the work ECE centers do is not only critical, but pivotal in the development of our youth. Across the city, they deserve adequate funding to build more centers, hire more qualified staff (or build capacity in current staff) and to be able to implement the necessary curricula to educate our babies. If the city would dig deeper, they too would realize that ECE is the answer to strengthening healthy families and that for true childcare sustainability, they need to begin by giving families who need them most, options.

Childcare centers should be where we need them! It amazes me to see where the city decides to put things. Let me tell ya, it’s not too often that resources are given to the neighborhoods that need them most. There are simply not enough childcare options east of the river. Parents need safe options close to home with individuals that understand their needs and how to best educate their children with the same amount of rigor presented in our more “well-to-do” wards. This pandemic has shown us that many of our families east of the river are essential or frontline workers, needing not only open childcare centers, but centers that could accommodate the hours needed for them to work. Our families need to work!

I also believe that accessible training options for ECE staff is vital to childcare sustainability. Staff should be able to consistently further their learning and convene routinely to share best practices. The city and the nation are vastly changing in the midst of this pandemic, and the education offered to the staff and children should reflect that. Once we realize that childcare center staff are more than caretakers and fund them accordingly by the roles they play, true sustainability may be reached. Childcare workers are teachers, co-parents, social workers, therapists, coaches, doctors and downright heroes!

To read more about the impact of COVID-19 in the District of Columbia, click here.

Feature photo by Kids’ Work Chicago Daycare (Source)

Chelsea Coffin is Director of the Education Policy Initiative at the D.C. Policy Center.

Amanda Chu is an Education Intern at the D.C. Policy Center.

Notes

[1] The Phase 2 Guidance for Child Care Facilities recommends daily health screenings for all children and staff, and requires all adults to wear non-medical face coverings or masks. There should be no more than ten individuals in one room, and individuals should be kept six feet apart. The guidelines also recommend staggered drop-off and pick-up times as well as curb- or door-side drop-off and pick-up. All children must be fully vaccinated to prevent a vaccine-preventable disease outbreak. Facilities must follow D.C. and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance on cleaning and disinfecting.

[2] Ninety percent of D.C. providers predict additional costs upon reopening in order to meet new safety and health standards and expectations.