For two weeks, we have been watching our lives, our economy, and our government dramatically change with the actions we need to take to limit the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. There is increasing consensus on the possibility of a deep global recession as the reduced economic activity in the service sector translates into loss of jobs and businesses, and potentially defaults, disrupting financial markets and amplifying economic losses. The District of Columbia is already feeling the impacts. The city has taken important steps to limit the spread of the COVID-19 disease and increase its capacity to attend those who are sick. But many more hard days and tough decisions await the District residents, workers, businesses, and policymakers.

What the District is doing

On March 17, the D.C. Council passed emergency legislation shaping the District government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Included in the legislation are timely and important interventions to support workers who are no longer able to work and businesses that are no longer able to operate.

For workers, the emergency legislation extends unemployment compensation and the Family and Medical Leave Act to cover those who lost their jobs or work hours because of COVID-19 disease. Furthermore, unemployment benefits tied to this change will not be included in the calculation of business experience rates to ensure that future unemployment tax obligations for employers do not spiral out of control.

For businesses, the emergency legislation postpones the payment of sales taxes (which should be paid monthly) until September 20 and delays the real property tax payment for hotels from the end of March to the end of June (an estimated $80 million in tax payments, according to publicly available records). The legislation also establishes small business grants (including to nonprofits and contractors, if they are not eligible for unemployment benefits). To ensure that these grants are distributed quickly, it allows their administration by a third party.

There are protections for households too. Evictions and the disconnection of gas, electricity, and water services for lack of payment are now prohibited. Throughout the public health emergency period, the Mayor can extend the eligibility duration or expand the eligibility criteria for public benefit programs including Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and the D.C. Healthcare Alliance and Immigrant Children’s Program (the District’s locally-paid health care programs for low-income residents who are not eligible for Medicaid or Medicare). The legislation also allows pharmacies to refill prescription drugs before the end of a waiting period.

(See the events that happened since the declaration of emergency in the District.)

What the federal government is doing

The federal government, too, is using all the tools it can to bring a level of stability to the economy.

The District has already qualified for federal grants for small businesses through the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA), which provides small businesses and private nonprofit organizations with targeted, low-interest loans they can use to pay fixed debts, payroll, accounts payable, and other bills.

The Treasury Department’s decision to delay 2019 income tax filings and payment by 90 days is essentially adding liquidity at a time when households need cash on hand more than before. On March 23, the Federal Reserve Bank announced that it will begin including in its buyback program corporate debt, including debt backed by consumer loans. (The Federal Reserve generally limits its buyback program to government-backed debt. The Federal Reserve’s changing role from a central bank to essentially a commercial bank can provide longer term stability in credit markets (but would require infusion of funds from the Congress.) Congress has passed, and the President signed into law, two new pieces of legislation: one supplemental appropriations bill to provide $8.3 billion in emergency funding for federal agencies to respond to the coronavirus outbreak, and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which extends paid sick leave to almost all workers (with some exceptions) and paid family leave to parents who are caring for children whose schools have closed. A third package (the CARES Act) is soon to be passed, with relief for businesses, and state and local governments, cash disbursements to families (with income limits), and investments in health.

How the District’s finances be likely impacted

The filing date for all District of Columbia income taxes for individuals, trusts and estates, partnerships, corporations, and unincorporated businesses have been extended to July 15, in alignment with the federal shift. Some income taxes are collected through payroll or estimated payments, meaning that while this delay will not impact all tax collections, it will delay the collection of a substantial amount. According to the D.C. Office of Revenue Analysis’ monthly revenue report for April 2019 (also known as the Monthly Cash Report), the District collected $539 million in income taxes last April (net of refunds); of this amount, $423 million was tax payments made by individuals, partnerships, and businesses. We do not know the numbers for this year, but under the extension, most of the cash revenue from income taxes due in April 2020 could be delayed.

The city is also delaying its budget submission and adoption processes, potentially to May 6th. The February revenue estimate from the Office of the Chief Financial Officer had projected a one-time $80 million increase in fiscal year 2020 revenues. This is no longer the case. The Chief Financial Officer noted during the March 17th legislative session that the current fiscal year’s spending might have to be cut back as much as $500 million.

And while the February estimates kept out-year revenues at the same levels as previously projected in December 2019, we should expect that to change as well. The Office of the Chief Financial Officer will likely rework and release the revenue estimates for fiscal year 2021 and onward before the Mayor submits her budget, and ahead of the usual release time of end of June. We do not know what those estimates could look like. But we have some experience that suggests that revisions will likely be drastic. For example, in 2008, when the impact of the Great Recession was not yet obvious, the February revenue estimates projected a total revenue of $6 billion two years out, for fiscal year 2011. By the time the recession’s impacts were abating and there were signs of recovery, the estimated revenue for fiscal year 2011 had been pulled back by about $1 billion to $5.06 billion.

The actions to delay tax collections (income taxes for all and property taxes for hotels) will further curtail future policy options by limiting the amount of cash available to the D.C. government, making immediate budget choices even more difficult.

How the COVID-19 crisis is different from the economic crises of the past

In the brief period of two weeks, we have been witnessing a collapse of the local, national, and global economies. What is different for the District of Columbia about this unfolding crisis, compared to the time after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, when the city experienced a similar shutdown, and the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, when the stock market losses and financial crises hit individual and corporate incomes and the housing market especially hard?

First, the demand shock from the COVID-19 pandemic and related public health actions is among the swiftest and deepest we have seen. Within just the first two weeks of March, hotel and restaurant activity came to a standstill. On March 15th, the last day restaurants were permitted to have in-house seating, the number of diners had declined by 77 percent compared to the same day last year, according to Open Table data. On March 19th, the number had fallen by 100 percent. According to information from Destination DC, during the week that ended on March 14th, hotels were at 47.3 percent capacity, a decline of over 42.2 percent compared to the previous year. And the changes are likely to be even more drastic for the following weeks. While a large share of D.C.’s workforce can continue to work from home, all sectors that serve commuters are also experiencing hardship. WMATA reports that transit ridership was down 70 percent on Monday, March 15th, before the system cut back on services, and was on March 18, putting the region’s already-fragile transit system into a further financial crunch.

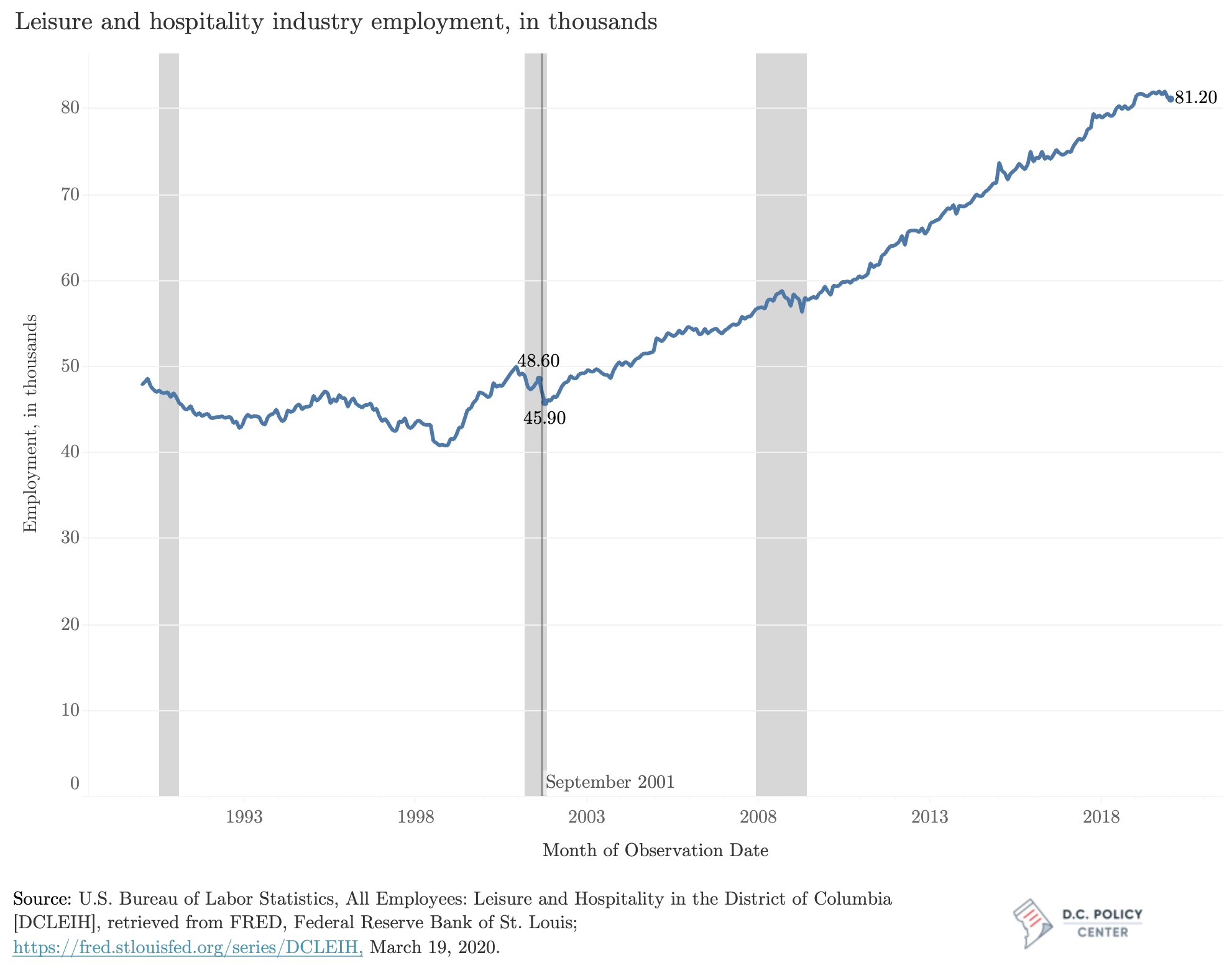

Compare this to the period after the September 11th attacks, when the city was also under a near shutdown. During that period, total employment in leisure and hospitality industries declined by 2,700 over the course of three months. That is a decline of 5.5 percent. It took the industry nearly a year to reverse the loss. In 2001, the leisure and hospitality accounted for about 11.3 percent of total private sector employment in the District; today, it is at 14.5 percent. And with the growth of the local workforce, the number of workers affected has grown even more: In 2001, the leisure and hospitality industry employed 48,000 workers; today, that number is 81,000.

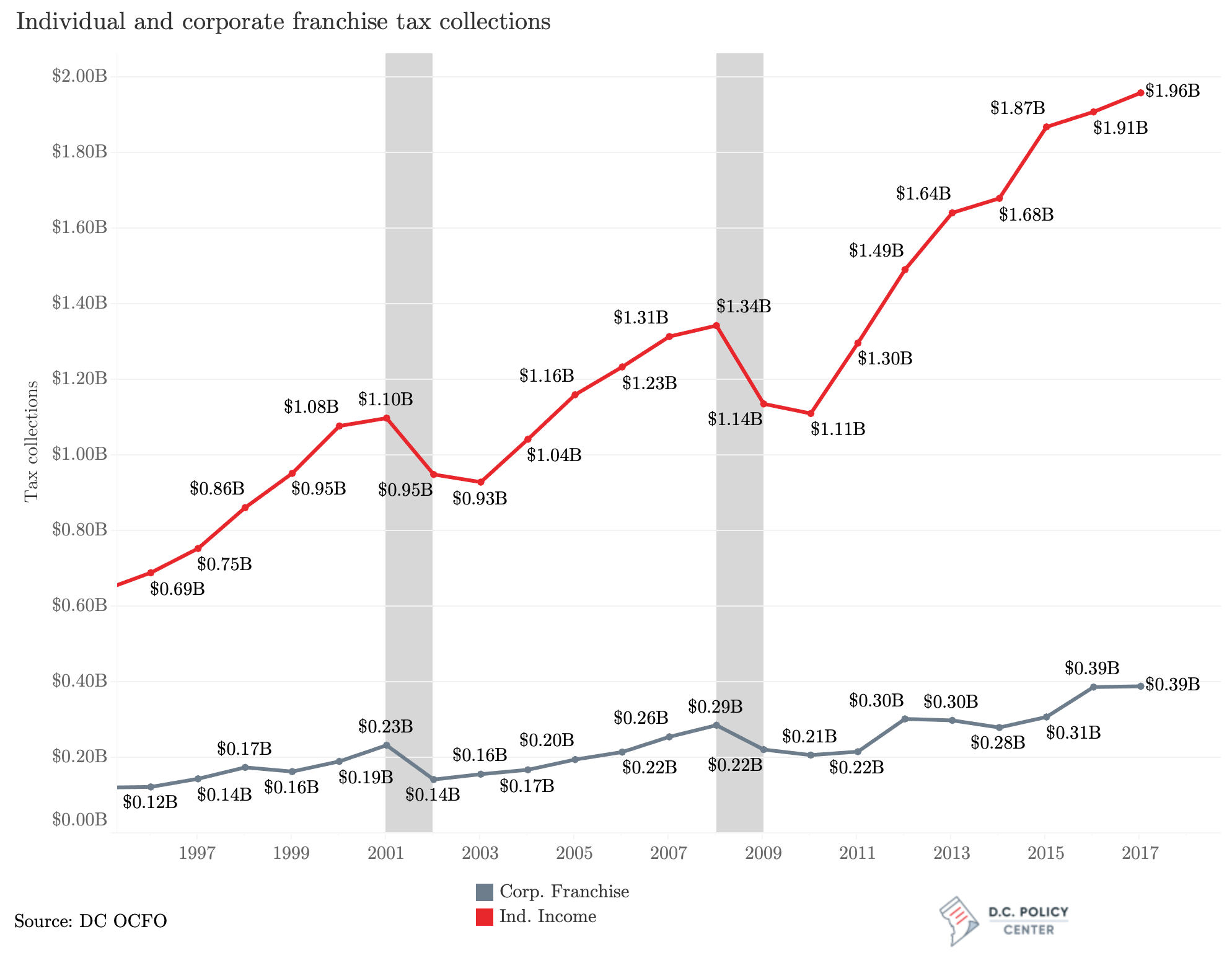

The pandemic’s impact on the markets have also been unprecedented, with no immediate end in sight. The Dow-Jones Industrial Average fell by 30 percent since the end of February (and 39 percent since its peak on February 13th), more than erasing all gains since 2017. That growth was a major source of tax revenue growth in the District of Columbia. If these stock market losses are not reversed, they will erode individual and corporate incomes and consequently individual and corporate income tax collections. We saw such declines both after the September 11th attacks (which was also in the middle of a recession) and during the Great Recession.

The double whammy of the demand shock (similar to after the September 11th attacks) and the financial crunch (similar to the Great Recession) is reverberating through the District’s economy. Between March 13th and March 23rd, unemployment claims increased by 18,082 to 19.460. Just those new claims amount to 3.1 percent of covered employment (578,035 as of March 7)—a rate we did not see even during the Great Recession. And this does not include those who were already receiving unemployment benefits (approximately 7,000 claimants as of March 7). To compare, through the worst of the Great Recession, the share of covered employees receiving unemployment benefits never exceeded 3 percent.

While the initial shock has hit the leisure and hospitality industry already, it will make its way through other sectors in the weeks and months to come. For example, the nonprofit sector, which employs an estimated 190,000 workers[1] (including 70,000 workers[2] in professional and trade organizations, civic groups, and grantmaking entities), might look significantly different in a few months. Many nonprofits rely on grants and donations—including donations they raise through events such as galas or other large gatherings—to survive. And many do not have significant amounts of cash in hand: According to the most recent data available (from 2017), 10 percent of nonprofits in the District do not have even a month’s worth of cash on hand, and 39 percent have three months or less.

These same financing constraints apply to small businesses as well. According to administrative data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are nearly 33,000 establishments in the District (reporting for unemployment insurance purposes) that hire fewer than 50 employees; they collectively employ nearly 200,000 workers (37 percent of all private sector employment) and pay about $18 billion in wage and salary incomes.

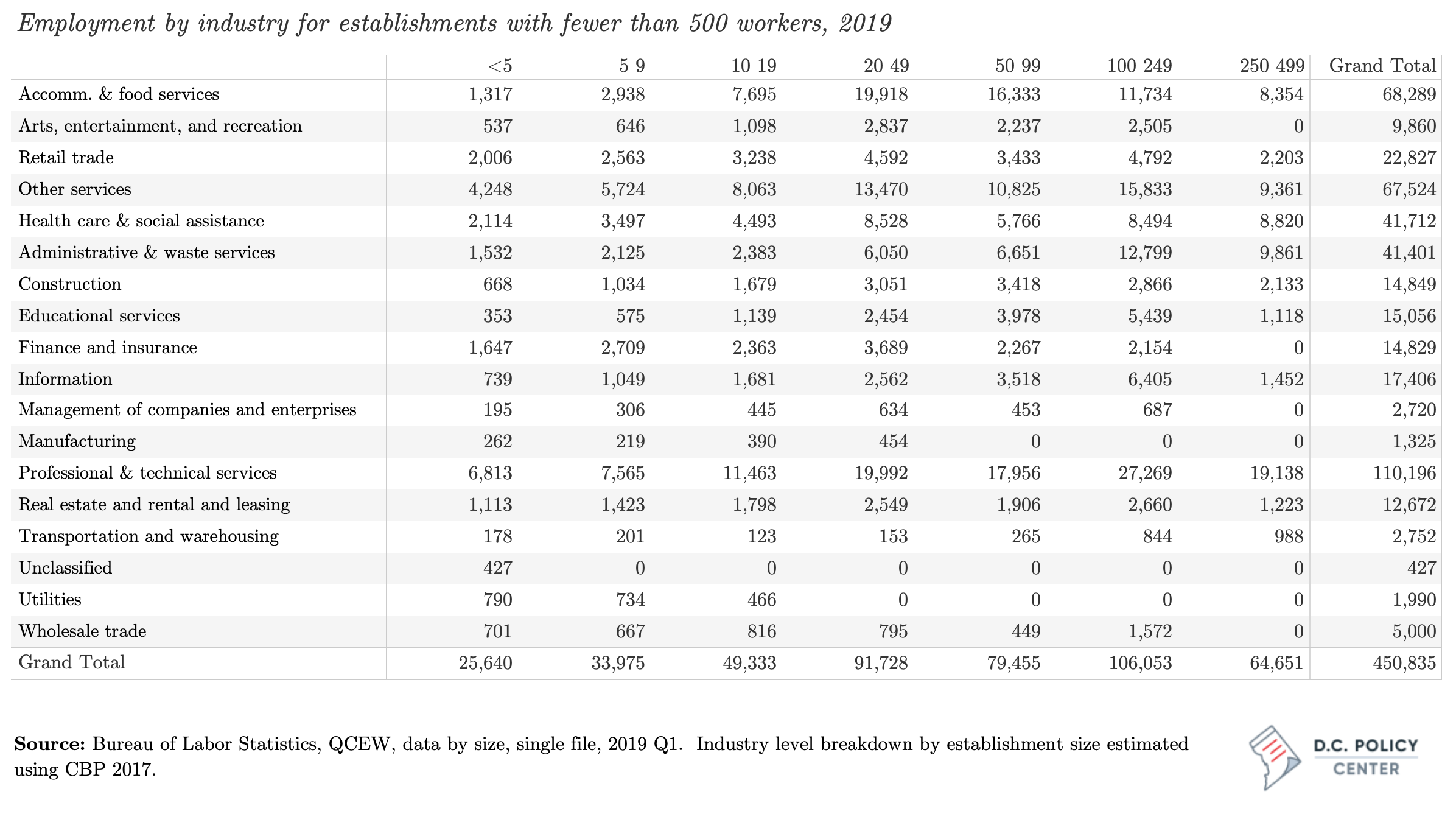

A 2016 study from the JP Morgan Chase Institute suggests that half of all small businesses in the U.S. with fewer than 500 employees hold a cash buffer of less than one month (27 days). And in industries that are hit first by the COVID-19 crisis, like restaurants, the median amount of cash-in-hand is much less, covering about 16 days. Although the study does not include specific information on the District of Columbia, if its findings can be applied to the city, the implications are dire: In the four sectors that have so far been hit the worst (hotels, restaurants, arts, entertainment, and retail trade), 16,000 establishments with fewer than 500 employees hire upwards of 169,000 workers. If one quarter of them immediately start laying people off because they lack enough cash to carry them beyond 13 days, the total number of workers laid off could be 44,000 in a matter of months.

The “stay at home” economy and the “in-person” economy

Finally, while many of the workers in D.C. and the broader metropolitan area can work from home, and therefore are protected from most of the immediate impacts of shutdown, many sectors require in-person interaction or travel to a specific place. For example, the “administrative and support and waste management and remediation” industry employs 46,000 workers in the city. This group includes people who work in office buildings (cleaning staff, security staff, and building managers, as well as temporary employees) who may be losing hours and pay. Personal services such as nail salons and dry cleaners (approximately 8,000 workers), and retail workers (23,500) are also taking a hit. The gig economy, including ride-hailing companies, are taking a hit. Ambulatory care services (19,000 workers) are likely being affected as well, as many dentists, orthodontists, and doctors’ offices are delaying or cancelling appointments. This will have an impact on our health, but also on the economy.

Importantly, we do not know the extent to which this new “stay at home” economy relies on the “in-person” economy. The secondary effects will be felt on other industries that sell services to the in-person economy: accountants who do the books for hotels, restaurants, and small businesses, architects who draw plans for retailers, and consultants who support small businesses may all have some contracts in hand, but will likely have much less work through the economic crises.

Capacity equals resiliency

The focus of public policy now is limiting the transmission of the COVID-19 disease. This will, by design, hurt our economy. While these actions are necessary, and must continue, they will also deplete—and in some cases, destroy—District residents’ and businesses’ capacity to bounce back when it is time to grow and thrive again. This makes it even more important to think about how to mitigate the economic impacts in the short term and build a more resilient local economy in the long run.

With a such great degree of unknowns, the central theme of this crisis is capacity. So far, the policy debate has focused on whether hospitals can handle the sick, whether the city’s large cash holdings can make up for future revenue losses, and whether the unemployment insurance trust fund can handle increased unemployment benefit applications.

We must also think of the District’s economy and its actors through this lens of capacity. Businesses, governments, and households are not like Lego bricks—one cannot dismantle them and rebuild them in the same exact way without losing something. Once dismantled, many will take a great amount of time to rebuild themselves, if they can at all. For businesses, rebuilding a productive team of employees will become harder if they had to lay off many employees. Similarly, financing could get harder if the business had to default on a loan or failed to pay back credit extended by vendors. For households, the implications of evictions or losing a job at at an older age do not magically disappear when the economy comes back. When households lose their financial assets, the impacts can last for years, impacting retirement decisions or higher education opportunities. Thus, short-term reactions to the current economic crises could hurt the long-term outcomes for the city, its residents, workers, and businesses.

Investing in this capacity today will be hard, but it will ensure that our losses will not be compounded. The next round of actions awaiting policymakers—including what happens through the budget formulation for fiscal year 2021 and rebalancing of the fiscal year 2020 budget—will likely be an incredibly difficult exercise in setting priorities for the city. Focusing on building this capacity is vital not only to weather the immediate impacts of the current public health crisis, but to build a more resilient economy for the medium- and long-term impacts that we cannot yet predict.

What the D.C. Policy Center is doing

With the economic picture changing so rapidly, we are working to create timely and high-frequency data that could inform the District government’s response to the crises.

-

- Take the small business survey if you are a business

- Take the nonprofit survey if you are a non-profit in the region.

- Email yesim@dcpolicycenter.org if you wish to partner for future data collection efforts.

Yesim Sayin Taylor is the Executive Director of the D.C. Policy Center.

Notes

[1] This is an estimate developed using the 2019 Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, based on the share of nonprofits in total employment information from 2017 County Business Patterns data.

[2] This is the total employment reported for religious, grantmaking, civic, professional, and similar organizations for January 2020 by the Current Employment Survey conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.