In the two years since a graduation controversy at Ballou High School exposed a serious student absenteeism problem across the city, D.C.’s traditional public schools and many of its public charter schools have deployed numerous interventions to improve attendance. Extensive evidence suggests that absenteeism undermines learning, beginning in very early grades. National studies have shown that absences in pre-kindergarten and kindergarten are associated with weaker reading proficiency in the third grade and poorer social skills. By middle school, absenteeism becomes a leading indicator that students will drop out of high school.

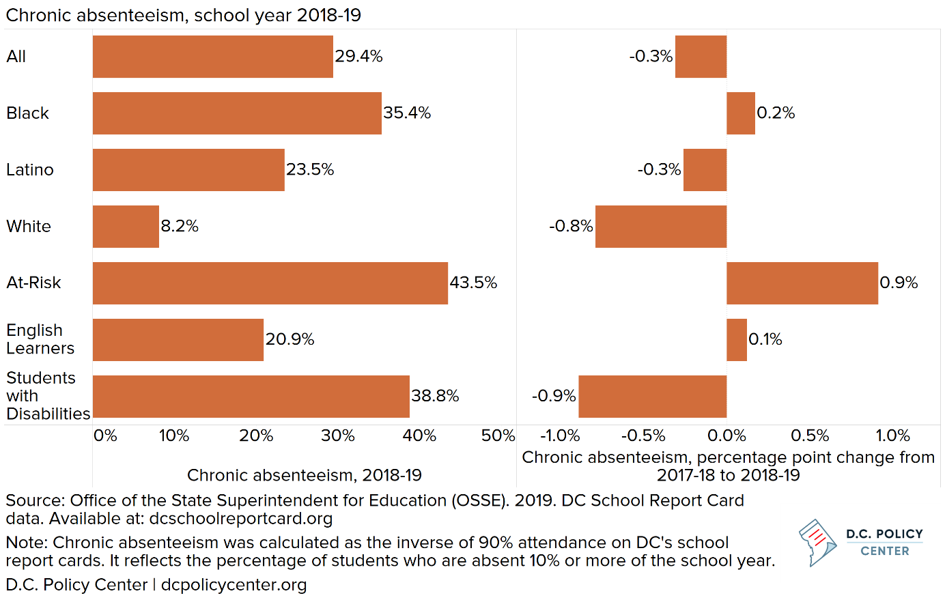

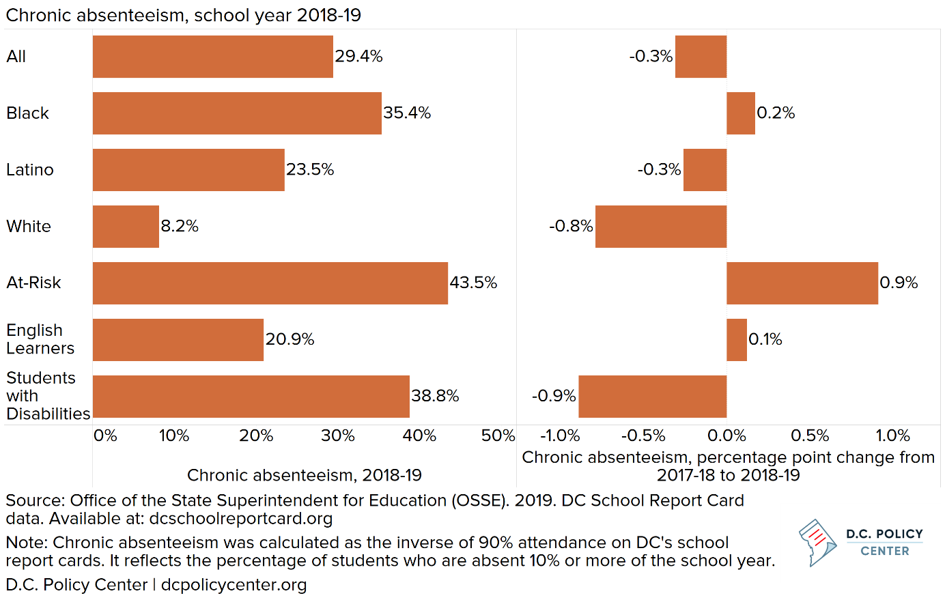

D.C.’s problem with chronic absenteeism extends to schools throughout the District. The latest data brought discouraging news in December, showing that attendance rates haven’t improved significantly since 2015-16. In fact, the share of students who are chronically absent – defined as missing 10 percent or more of the school year for any reason, excused, unexcused, or disciplinary – actually increased slightly between 2017-18 and 2018-19, to 30 percent, the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) reported.

While the District tracks missed school in a number of ways, chronic absenteeism has emerged as a key metric to highlight high levels of absences for particular students and trends in attendance. Officials can look at daily school-wide counts of in-seat attendance, reflecting how many students show up every day, but this approach doesn’t capture who is missing too much school or why. Schools also track truancy, the number of days students miss without an excuse. When unexcused absences reach a certain threshold, students are referred to other agencies. While tracking truancy is important, the punitive response it evokes often does little to improve attendance for students facing such barriers as poor health or unstable housing. And because truancy largely happens in the older grades, the data ignore what’s happening in the early years.

Chronic absenteeism captures the loss of instructional time at any age and for any reason – with or without an excuse – when students miss at least 10 percent of the school year. Addressing it requires more holistic solutions that engage students and families, improve school climate, and address the broad range of reasons student don’t attend class.

D.C. has implemented several promising strategies to improve student attendance. A pilot shuttle service takes homeless students to school. Teachers in more than 60 schools across the city are visiting families at home to build stronger relationships. And some District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) and KIPP public charter schools are sending home thousands of letters and emails about students’ attendance records, based on approaches that have produced impressive results elsewhere.

But these new interventions have been introduced only recently or are in the pilot phase, and have not yet had a measurable impact. Other reforms, such as programs focusing on the transition into high school, have been in place longer but have suffered from inconsistent implementation. Reporting on the results of a recent audit his office conducted of the city’s attendance initiatives, Deputy Mayor for Education Paul Kihn told the D.C. Council that “We’re doing a lot, but [these interventions are] only working in some schools.”

Hitting High Schools Hardest

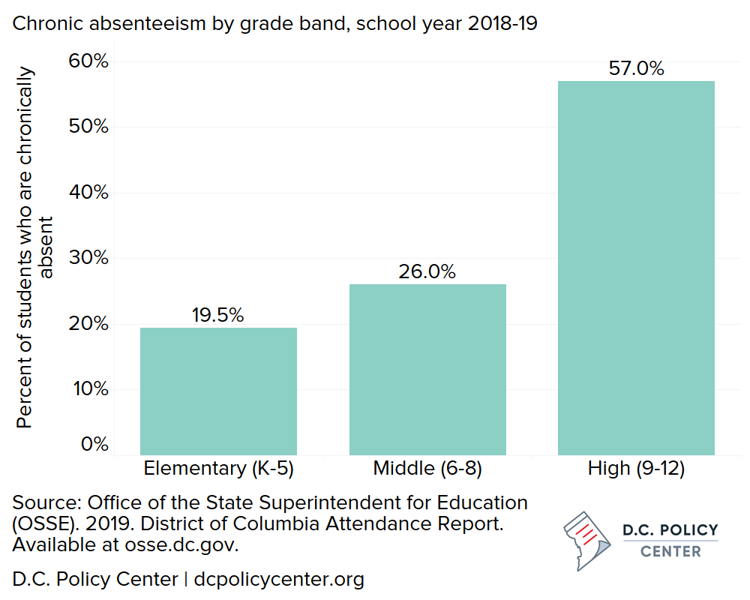

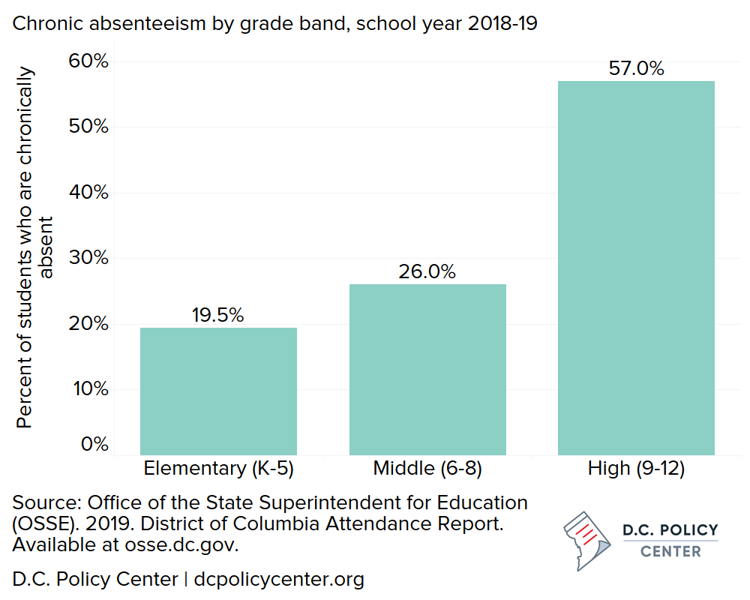

As in other cities, D.C.’s problem is most severe in its high schools, where more than half of students citywide are chronically absent. Some schools have reduced their very high rates of absenteeism, but more have seen their rates rise in the past four years. Altogether, 13 high schools have chronic absenteeism rates higher than 75 percent, according to OSSE data.

Throughout the District, the increase in chronic absenteeism when students transition from middle school to high school is particularly troubling: 28 percent of all 9th graders missed at least a third of the 2018-19 school year—54 days or more, compared to about 5 percent of 8th graders.

Absenteeism often begins early in a student’s education. About a third of all D.C. pre-kindergarten students and a quarter of kindergartners are chronically absent according to the OSSE report, putting students’ progress at risk. A study in Chicago found that students who are chronically absent between preschool and second grade have significantly lower learning outcomes at the end of second grade than their counterparts who are not chronically absent in the early years.

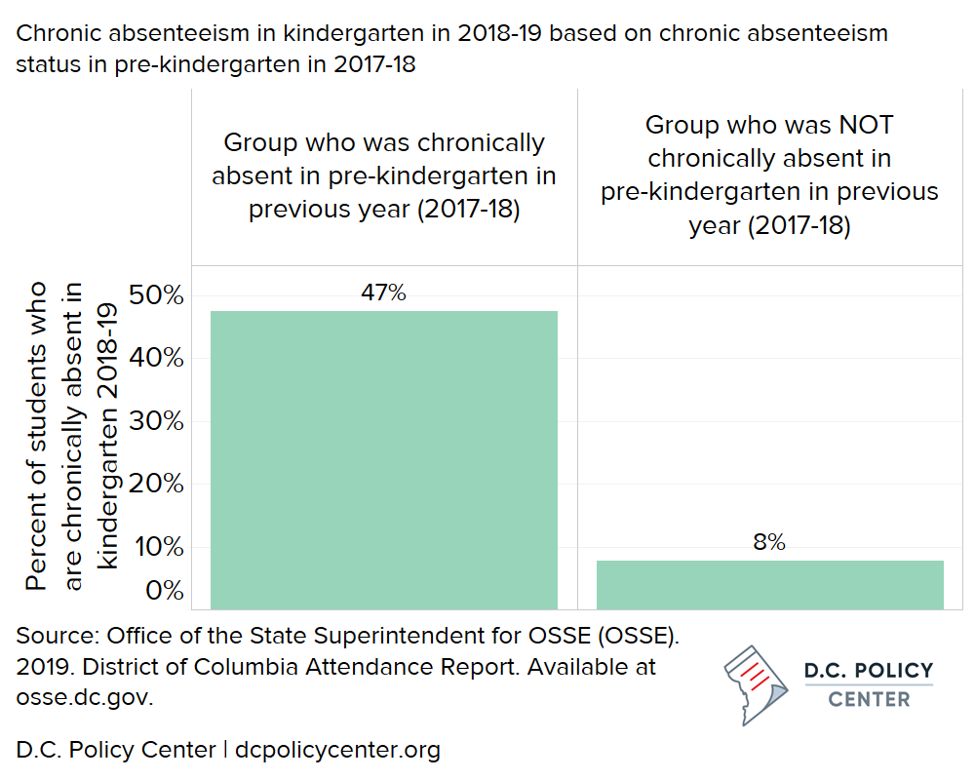

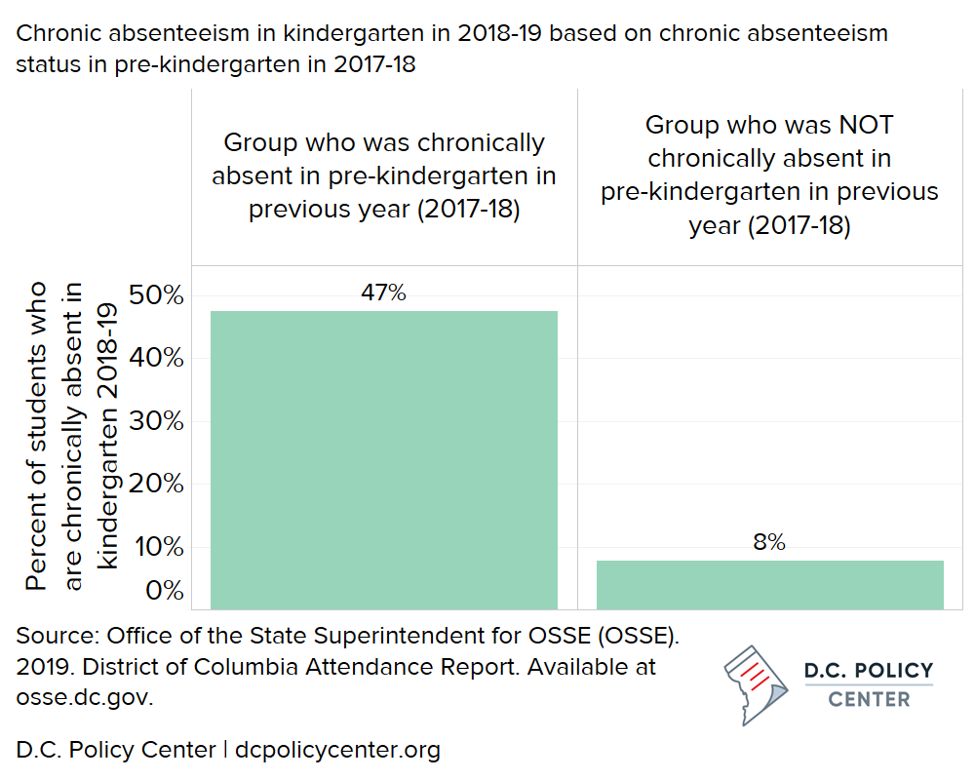

While attendance is not compulsory in pre-kindergarten, these absences are powerful predictors of future attendance patterns. The OSSE report found that pre-kindergarten students chronically absent in 2017-18 were about six times more likely than their peers to be chronically absent in kindergarten in 2018-19.

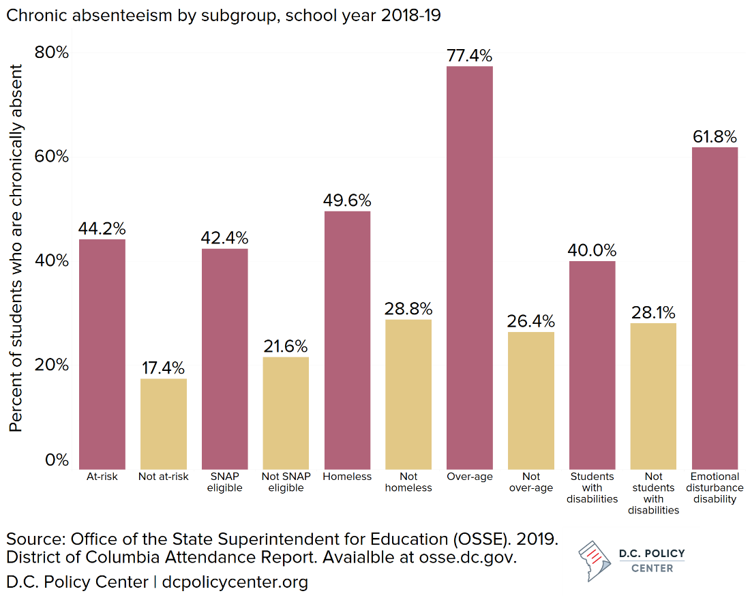

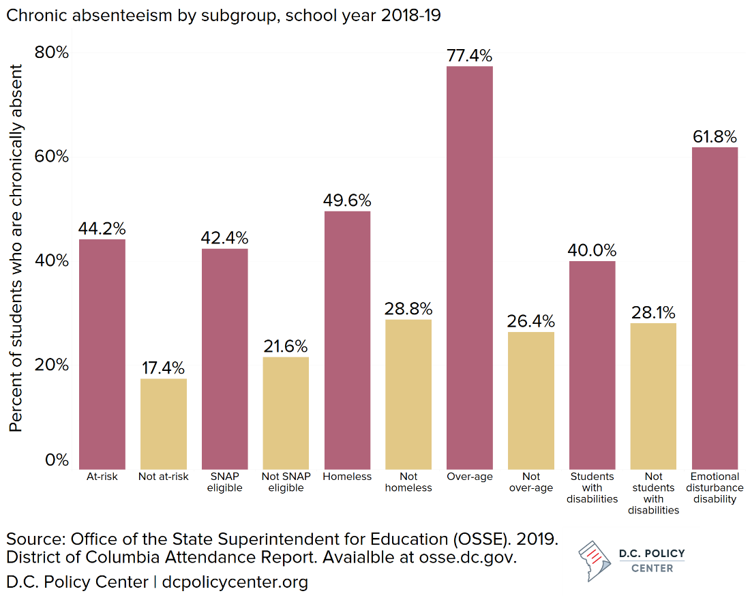

This issue is not confined to D.C.; the city’s attendance problems mirror those of other urban school districts. As in D.C., rates are considerably higher among students living in poverty, particularly those who are homeless or who move frequently. Students who are over-age for their grade also tend to miss more school. So do students receiving special education services, especially those identified as having an emotional disturbance.

What Works

Recognizing the importance of chronic absenteeism, FutureEd and Attendance Works collaborated to develop a playbook exploring the best approaches to improving attendance. D.C. traditional public and charter schools have already adopted many of the evidence-based strategies that have produced impressive results elsewhere, including information sharing, family engagement, transportation assistance, and improving the school environment.

Information Sharing

One key step D.C. officials have taken is developing a system for tracking and sharing student data not just within the education sector but across city agencies.

All schools receive reports on student behavior and attendance every week, through a system that has been instituted in the past two years. High school principals receive a monthly report that includes information on which students are on track for graduation, and which are not. The DCPS central office reviews school-level data every week and reaches out to schools when they notice high or growing rates of absenteeism. The District of Columbia Public Charter School Board (DC PCSB) follows up with charter schools showing particularly high truancy rates.

In addition, DCPS requires schools to have an attendance plan with annual improvement goals. Designated staff members track data, and school teams—teachers, counselors, nurses, and sometimes community partners—review the data regularly to brainstorm solutions. The school district also brings together attendance officers from clusters of schools to share strategies.

Importantly, the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education’s Every Day Counts taskforce connects the traditional public and charter sectors with at least 14 other D.C. government agencies, ranging from social services to transportation. By cross-referencing Metropolitan Police Department data and attendance records, for example, OSSE researchers found a small, but statistically significant, increase in absenteeism the day after a violent crime occurred within 1,000 feet of a student’s home. Officials are now exploring how best to respond to the insight. Children’s National Hospital is working to integrate attendance data into pediatrician’s visits, so doctors can address physical and mental health issues that could affect absenteeism.

Engaging Families

Some of the initiatives that are showing promising results involve engaging families through home visits and other methods. For example, DCPS and the charter network KIPP DC are working with the Harvard University-based Proving Grounds project to expand a pilot program alerting families to just how many days children have missed. Research shows that most parents and caregivers don’t know how many absences have accrued and believe their children have missed fewer days than other students. By sharing absenteeism numbers every six or eight weeks, DCPS schools involved in the pilot program saw a 2.7 percent increase in attendance rates. If these results held citywide, that would equal 17,000 fewer absences across DPCS. The pilot schools in the KIPP network saw a 3.4 percent increase.

In the 2019-20 school year, the program has expanded to more schools, which collectively sent out about 19,000 notices in early November. In a related pilot, some kindergarten teachers in DCPS and KIPP DC charters are mailing handwritten postcards to families whose students miss school. The postcards include not only positive messaging about attendance, but also details about what lessons the students missed.

DCPS and the charter sector are also expanding a home visiting program that has reduced absences in many schools. Under the program, supported by Flamboyan Foundation, teachers visit families at home to build relationships. A study of 12 D.C. schools by Johns Hopkins University found students whose families received home visits had 24 percent fewer absences than similar students whose families did not receive a visit.

Philanthropic and community-based organizations are also involved in addressing chronic absenteeism. For example, the District’s Office of Victims Services and Justice Grants works with seven community-based organizations in about 80 schools to help families address unique challenges under a program called Show Up, Stand Out. The support can be as simple as providing a SmarTrip so parents and caregivers can take young children to school. Or it can mean helping a family find an affordable place to live. The program received more than 3,100 referrals in 2018-19 and helped nearly 400 students. While 79 percent of families saw improvement in their children’s attendance after receiving assistance, those gains were not enough to move the needle on overall absenteeism rates in four of the six high schools where the program operates.

Getting There

Transportation is often a challenge in a city where only 29 percent of pre-kindergarten to grade 12 students attend their neighborhood school and the average commute to school is 2.2 miles.[1] D.C. already provides all students with free transit passes, but many still have complicated routes to school (42 percent of students leave their home ward to attend school).[2] An ongoing study by the D.C. Department of Transportation is evaluating how transit patterns relate to attendance. DC PCSB conducted its own analysis in spring 2019 that showed students using transportation services offered by public charter schools had lower levels of absenteeism than peers.

Transportation is particularly challenging for homeless students, who often find themselves moving far from school. Under a pilot program, families experiencing homeless at certain sites can receive SmarTrip cards, gas money, or rideshare vouchers to get their children to school.

For students walking to school, safety can be a concern. With a grant from the D.C. government, Richard Wright Public Charter School deploys a “Man the Block” program that posts volunteers along the route to school near the Navy Yard in Southeast. Another grant funds a similar program near the Minnesota Avenue Metro station. Altogether, a D.C. working group has identified seven neighborhoods that could benefit from safe-passage programs, and the District is launching pilots in those areas. While D.C. has yet to report results from these new efforts, research shows such Safe Passage programs have reduced absenteeism elsewhere.

A Welcoming Place

Once students get to school, it’s essential that they feel safe, welcome, and respected there. A welcoming school climate one where students develop a sense of belonging and build strong relationships with teachers—is associated with better attendance and achievement, studies show. DCPS schools administer climate surveys to students and teachers and use the results as they develop attendance plans. Additionally, a Proving Grounds pilot program is connecting students with mentors, either community volunteers or school staff members, who check in with students regularly and call them when they miss school. These connections can enhance the sense of belonging at school that is crucial to good attendance.

Some of D.C.’s efforts have paid dividends, especially in schools that establish cultures welcoming to student and their families.

Ward 7’s J.C. Nalle Community School, for example, cut its chronic absenteeism rate in half in 2018-19, to 10 percent, using a combination of engagement strategies (such as allowing students to participate in out-of-uniform days on Friday if they show up Monday through Thursday) and attention to the root causes of absences (such as housing instability and transportation challenges) among its 425 students. The Nalle team works with external agencies to address the challenges, which can range from dental care for children to financial literacy and employment training for adults.

At Friendship Collegiate Academy Public Charter School, chronic absenteeism dropped by 20 percentage points, from 46 percent in SY 2017-18 to 26 percent in SY 2018-19. The Ward 8 high school, which serves 573 students, provided incentives for showing up early, asked families to sign attendance contracts to commit to improved attendance, and offered one-on-one counseling for absentee students. This year, the school has also adopted a swing schedule for students who take younger siblings to school or have other conflicts, giving them opportunity to take classes from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. instead of the standard 8 a.m. to 3 p.m.

However, other efforts have not had significant results. Since 2013, for example, DCPS has used ninth-grade academies to focus attention on students during a difficult transition. In Chicago, this intensive focus on freshmen has led to better attendance, grades, and graduation rates. In D.C., the results have been mixed, with increases in chronic absenteeism in all eight schools using this model.

A problem as complex as chronic absenteeism cannot be solved overnight, and D.C.’s political leaders should give education officials more time to expand existing pilot programs and scale the results. But teachers and school administrators also need to implement these programs more consistently, both within schools and across the school system. Schools can’t be expected to solve all the problems that keep students from getting to class, but evidence shows that they can help reduce those barriers and make school a place where students feel welcome and respected—a place where they want to show up every day.

Feature photo by Ted Eytan (Source)

Phyllis W. Jordan is editorial director of FutureEd, a nonpartisan think tank at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. She is author of the Attendance Playbook produced jointly with FutureEd and Attendance Works.

Notes

[1] Deputy Mayor for Education (DME). 2019. EdScape Beta: “Enrollment Patterns.” Available at edscape.dc.gov.

[2] Deputy Mayor for Education (DME). 2019. EdScape Beta: “Enrollment Patterns.” Available at edscape.dc.gov