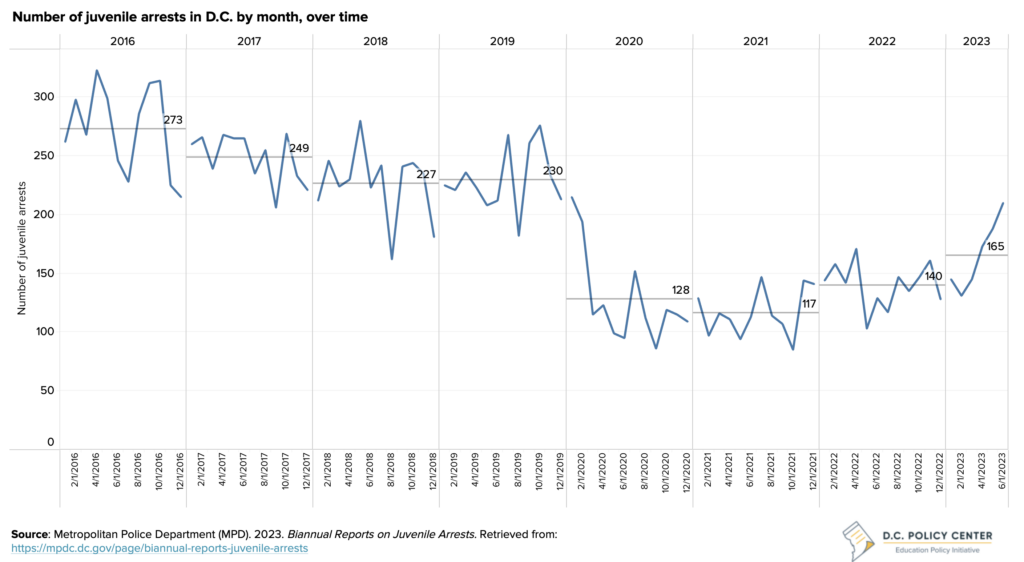

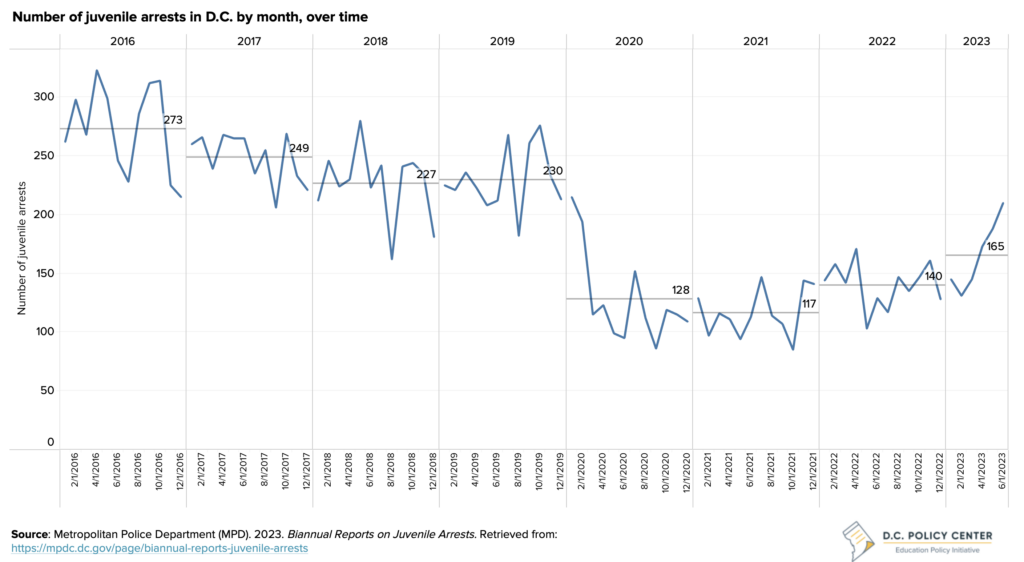

Juvenile arrests are common in the District of Columbia. Between 2016 and 2022, on average Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) officers arrested 2,235 juveniles in a given year involving youth under the age of 18.1 This is an average of 52 arrests per 1,000 children and youth between the ages of 10 and 17. This arrest rate is nearly twice what prevailed across the country.2 To put this into context, between 2016 to 2022, there were an average of 45,041 youth in the District aged 10-17.3

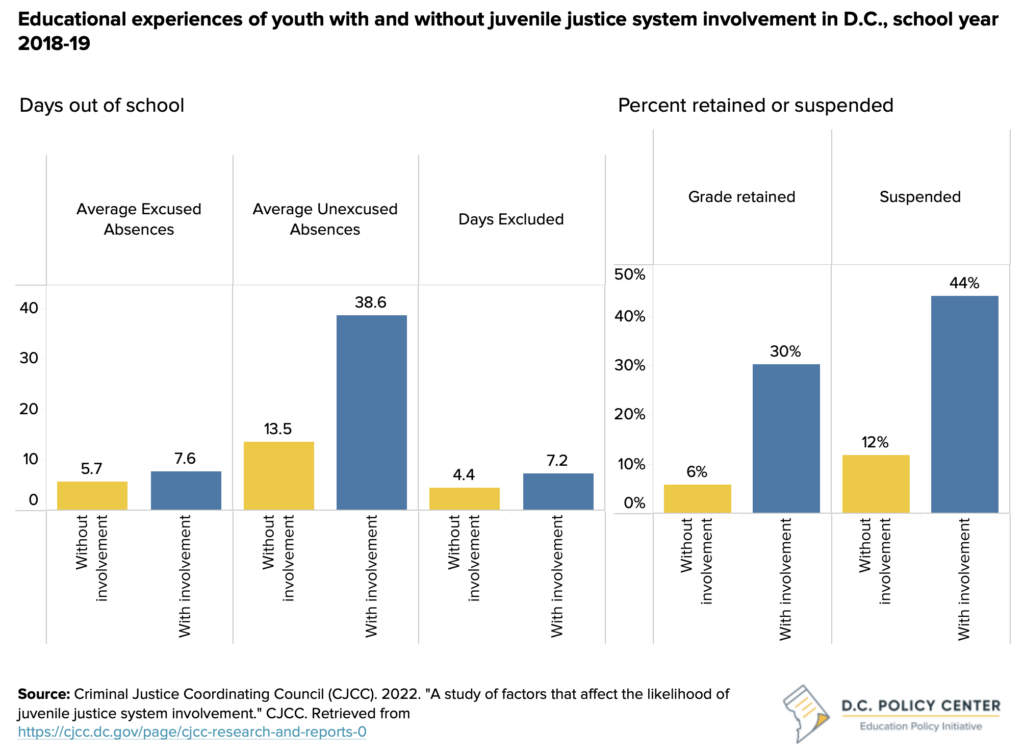

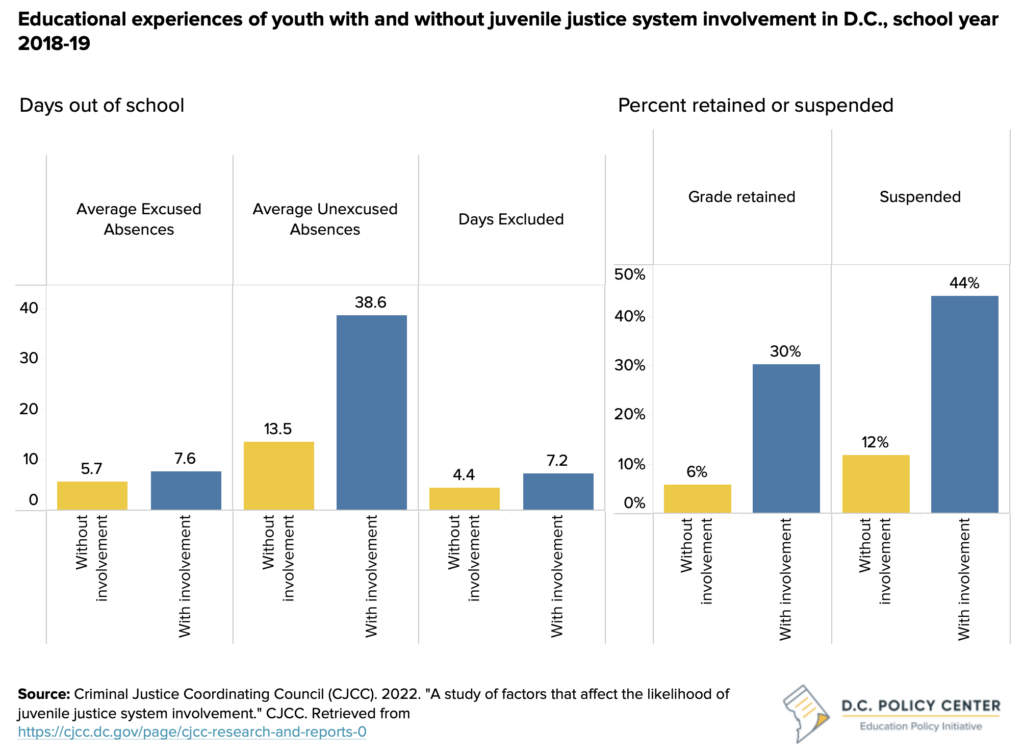

To put this in perspective with D.C.’s child and youth population, D.C.’s Criminal Justice Coordinating Council (CJCC) found that 4 percent of public-school youth over 10 years old and under 18 years old became involved in the juvenile justice system4 between school years 2018-19 and 2019-20.5 These youth in D.C. who were justice-involved were 15.5 years old on average, more likely to be male, Black, experience homelessness, and be eligible for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Factors related to juvenile-justice involvement included economic resources; education experiences; mental, behavioral, and development disorders; and neighborhood environment.6 For school-related outcomes, juveniles with justice system involvement are more likely to be retained in a grade, have more unexcused absences, and have more suspensions.7

Chronic absenteeism, having at least one open case from the D.C. Child Family Services Agency (CFSA), and being removed from the home by CFSA, are all statistically significant with being involved in the juvenile justice system.8 In school year 2021-22, the percent of students missing 10 percent or more of school peaked at 48 percent, 20 percentage points higher post-pandemic.9 While chronic absenteeism doesn’t necessarily imply that all youth who are chronically absent will then be involved in the juvenile justice system, it does expose other issues that are likely impacting students’ academics, housing opportunities, transportation, and physical and mental health wellness.10

We asked individuals from multiple institutions that serve incarcerated youth how D.C. can better serve its incarcerated youth.

Note: It is important to note that we have been working on this piece for over two months. The past few weeks show that this is an urgent issue. When crimes by young people happen with more severity, it is important to balance long-term preventative programs with immediate interventions.

Felecia Hayward, Deputy Chief of Secure Programs for See Forever Foundation, Maya Angelou Schools

The most effective strategy to mitigate juvenile justice system is early intervention. When youth are struggling with compliance, behavior, and attendance, providing intervention for them and their families is what we see as being most effective. Time and time again though, we find that interventions tend to happen when it’s too late because when youth are in late middle school or early high school, they’re more likely to be involved in deviant behavior.

Cultivating a welcoming and open school environment for students and families is also important in mitigating juvenile justice involvement. If families have had prior negative experiences with school, particularly parents with language barriers or struggling with disabilities, it’s all the more paramount that schools are safe havens with accountability measures in place.

We see a major disconnect between providing support for youth after their juvenile justice involvement, and we are working towards bridging the gap to make that transition easier. There must be a more natural progression of going from 100 percent supervision daily to none. If the youth and their families don’t have support in this process, they are more likely to fall into previous behaviors. Instilling soft skills, career exploration opportunities, resuming building, and providing educational chances that allow students to make money legally are all approaches that need to be incorporated more when supporting these youth.

We are also uplifting teacher pay equity for teachers at our schools. We know that research supports having strong teacher investment in youth is more beneficial for youth socially, academically, emotionally, and more. It’s particularly difficult retaining highly-qualified, trained individuals that are willing to work with these students especially given the discrepancy between public school teacher pay and teachers at our schools, and this is something we will continue to uplift because our students deserving of caring, skilled adults in their education career.

Melissa Milchman, Senior Grants Manager and Juvenile Justice Specialist at D.C. Office of Victim Services and Justice Grants

One of the major challenges seen in alleviating juveniles being involved in the justice system is the silos between agencies. The challenge with D.C. and statehood comes into play with juvenile justice because many agencies operate in different capacities, and they all have different authorities they report to. It’s increasingly difficult when local, federal, and independent agencies all have different visions for what implementation looks like for cohesive, collaborative strategies to reduce juveniles being involved in the justice system.

Even with the difficulty of inter-agency collaboration, a key strategy in reducing this burden is engaging young people with healthy, positive relationships. This can look like mentoring, building more organizations that are aligned with students’ interests and values. ROCA, an evidence-based program that works closely with young people on a weekly basis to provide interventions and support.

The Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, an independent District agency, has done multiple studies on the root causes and risk factors associated with youth being involved in the juvenile justice system.11 It’s clear the District is invested in doing research on the whys behind being involved, but we do have lengths to go to create healthy spaces for our youth and give them access to non-punitive consequences for their behaviors.

Eduardo Ferrer, Visiting Professor at Georgetown Law Juvenile Justice Clinic, Policy Director of the Georgetown Juvenile Justice Initiative

The District must consider investing directly in young people, their family, and their communities. When communities, families, and young people are healthy, they thrive, and that looks like ensuring that everyone has what they need.

Prevention of juvenile delinquency includes prevention and intervention. Prevention in the form of direct cash assistance, home visits for young parents and their families not in a pejorative manner, and providing safe, affordable housing. Intervention looks like creating “programming helps young people heal early on.” Parenting supports not just at birth or birth to 5, but birth until young people are ready to leave their homes. Juvenile delinquency is often a multi-generational problem which is why the District must invest directly in young people and their families’ healing and increasing behavioral health supports.

Georgetown Law Juvenile Justice Clinic analysis of the budget at the Committee on the Judiciary and Public Safety Budget Oversight Hearing on the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) concluded that instead of spending $30 million dollars on more officers, these funds should be spent on more violence interrupters, credible messengers, or school based social workers. Another viable solution would be the expansion of D.C.’s universal basic income or direct cash assistance pilots.

The clinic’s work on juvenile justice delinquency is working to ensure that the District’s system is “the smallest, the best, and the most just.” The resources currently available are not serving youth in the best way, and they need to be allocated to prevent harm in the first place.

Attorney General Brian Schwalb, Office of the Attorney General for the District of Columbia

The Office of the Attorney General (OAG) is committed to ensuring the safety of the District’s residents, in the present and future. Because the District’s criminal justice system is unlike any other’s because D.C. is not a state, the OAG’s office only has authority over juvenile crime and specific adult misdemeanors.

The OAG addresses juvenile crime through analysis, data, evidence, and history. Using sufficient and admissible evidence to meet the burden of proof, the office prosecutes juvenile cases, and when community safety requires it, secure detention is sought out. Nevertheless, the OAG works to provide the resources and supports youth need to prevent them from re-offending.

The office is also committed to developing innovative, evidence-based alternatives to traditional prosecution, and that includes violence interruption, truancy, prevention, and restorative justice. Allowing victims and community members to receive the care and resources they need and deserve is a salient approach the office engages in as well.

Response to juvenile crime in the District always hinges on the needs of the community and the juvenile involved and being flexible in determining the best path forward. The Office of the Attorney General works closely with law enforcements that include the U.S. Attorney’s Office, the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), and jurisdictions in Maryland and Virgina, in a collaborative effort to solve crimes and address criminal activity.

In summation, the Office of the Attorney General understands that in order to make D.C. safer, prevention measures through focusing our resources on strategies is necessary. Investment in programs and processes that identity at-risk youth and provide interventions for them and their families, ensuring high-quality access to address trauma and mental health issues, keeping students in schools, and youth programs tailored towards violence interruptions are all essential in keeping children out of the criminal justice system.

Endnotes

- Note: The Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) is the primary and largest law enforcement agency for the District of Columbia. Aside from MPD, there are multiple law enforcement agencies working within the District.

- Note: Metropolitan areas account for the vast majority of arrests according to the Vera Institute of Justice.

- Annie Casey Foundation. Child population by age in the District of Columbia. Retrieved from https://datacenter.aecf.org/data/tables/100-child-population-by-single-age?loc=10&loct=3#detailed/3/any/false/1095,2048,574,1729,37,871,870/52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60/418

- Justice system involvement in this analysis indicates any contact with the justice system from arrest through conviction. It does not mean that a youth has been adjudicated delinquent or found guilty of any charge

- Criminal Justice Coordinating Council. (2022, October). A study of Factors that Affect the Likelihood of Juvenile Justice System Involvement. Retrieved from https://cjcc.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/cjcc/CJCC%20-%20A%20Study%20of%20Factors%20that%20Affect%20the%20Likelihood%20of%20Juvenile%20Justice%20System%20Involvement%20%28October%202022%29.pdf

- Criminal Justice Coordinating Council. (2022, October). A study of Factors that Affect the Likelihood of Juvenile Justice System Involvement. Retrieved from https://cjcc.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/cjcc/CJCC%20-%20A%20Study%20of%20Factors%20that%20Affect%20the%20Likelihood%20of%20Juvenile%20Justice%20System%20Involvement%20%28October%202022%29.pdf

- Criminal Justice Coordinating Council. (2022, October). A study of Factors that Affect the Likelihood of Juvenile Justice System Involvement. Retrieved from https://cjcc.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/cjcc/CJCC%20-%20A%20Study%20of%20Factors%20that%20Affect%20the%20Likelihood%20of%20Juvenile%20Justice%20System%20Involvement%20%28October%202022%29.pdf

- Criminal Justice Coordinating Council. (2022, October). A study of Factors that Affect the Likelihood of Juvenile Justice System Involvement. Retrieved from https://cjcc.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/cjcc/CJCC%20-%20A%20Study%20of%20Factors%20that%20Affect%20the%20Likelihood%20of%20Juvenile%20Justice%20System%20Involvement%20%28October%202022%29.pdf

- D.C. Policy Center.2022. State of D.C. Schools, 21-22. Retrieved from https://dcpolicycenter.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/SODCS-21-22-web.pdf

- D.C. Crime Facts. 2023. Preventing crime by keeping kids in school. Retrieved from https://dccrimefacts.substack.com/p/fighting-crime-by-keeping-kids-in

- The CJCC has multiple roles within the District to increase public safety and identify challenges and solutions related to the justice system.