One topic that came up in the recent fight over the fiscal year 2018 Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) budget—and that tends to come up whenever subsidies for WMATA are discussed—is that the District of Columbia’s government is generally more eager to pay for Metro than the governments of Maryland and Virginia.

Decisions about funding WMATA require agreement between these three jurisdictions, since it would be unfair to expect the District to unilaterally increase its subsidy. However, it would make sense for the District to look for ways to spend money on improving transit for its own residents.

Lower fares within the District could be subsidized

The conflict between the District and suburban jurisdictions about funding Metro is natural: Per-capita transit ridership is significantly higher in the District, partly because it’s generally easier to commute by transit in the denser areas of the region and partly because a sizable fraction of suburban residents does not commute into the city.

Furthermore, the state governments in Annapolis and Richmond are the parties to the WMATA contract, not the local governments in the Maryland and Virginia suburbs, and the priorities of the state legislatures and governors don’t always align with those of the local jurisdictions.

In the longer term, Metro funding is a regional problem that requires a regional solution. The Metrorail system serves many passengers who cross jurisdictional boundaries as part of their daily commutes and all jurisdictions must contribute to the system’s proper maintenance.

However, Metrorail ridership is currently in a death spiral, with service reductions—made worse by closures and single-tracking necessitated by repairs—and high fares leading to decreased ridership that makes the system’s financial situation even worse.

Short-term fixes are worth considering along with necessary longer-term reforms. One possibility that would benefit a sizable fraction of Metrorail riders without requiring additional subsidies from the suburban jurisdictions would be for the District government to subsidize Metro trips entirely within the District.

This sort of subsidy would not be unprecedented

Metrorail’s rather unusual distance-based fare collection system—only two other American rapid transit systems use it—in which patrons swipe their SmartTrip cards both when entering and when exiting the system makes it practical to subsidize only certain trips.

If the WMATA Board and the District agreed, fares on trips within the District could be reduced in exchange for an additional District subsidy for WMATA intended to keep the change revenue-neutral. Such a use of District funds would be reasonable as it would primarily benefit District residents—whose commutes are often entirely within the city—and District businesses, since it would encourage travel within the city.

This also wouldn’t be an unprecedented fare policy. BART in San Francisco, the country’s other large rapid transit system that uses distance-based fares already does something similar.

Along with surcharges for using airport stations and subsidies for certain suburban trips, BART charges higher fares for trips to, from, or within San Mateo County, which is not a member of the Bay Area Rapid Transit District and does not contribute to funding the system.

BART’s rather complex system of surcharges is responsible for the wide range of prices for trips of the same length that I found in my earlier discussion of Metrorail’s fares in comparison to other rapid transit fares in the U.S.

Although BART’s complex fare system works, it is worth noting that my proposed discount for trips within the District would not lead to nearly as complicated a system as BART’s combination of multiple surcharges.

Furthermore, a small subsidy, such as rolling back the $0.25 Metrorail fare increase included in the fiscal year 2018 budget, would not result in an overly large jump in fares at the District’s borders.

How much would it cost?

Of course, no matter how practical this plan might be, it will only be politically viable if the required subsidy from District taxpayers is not too large.

In order to determine how much a subsidy for Metrorail trips within the District might cost, I used Metrorail’s data on system entrances and exits to determine what fraction of Metrorail’s trips would qualify for the subsidy.

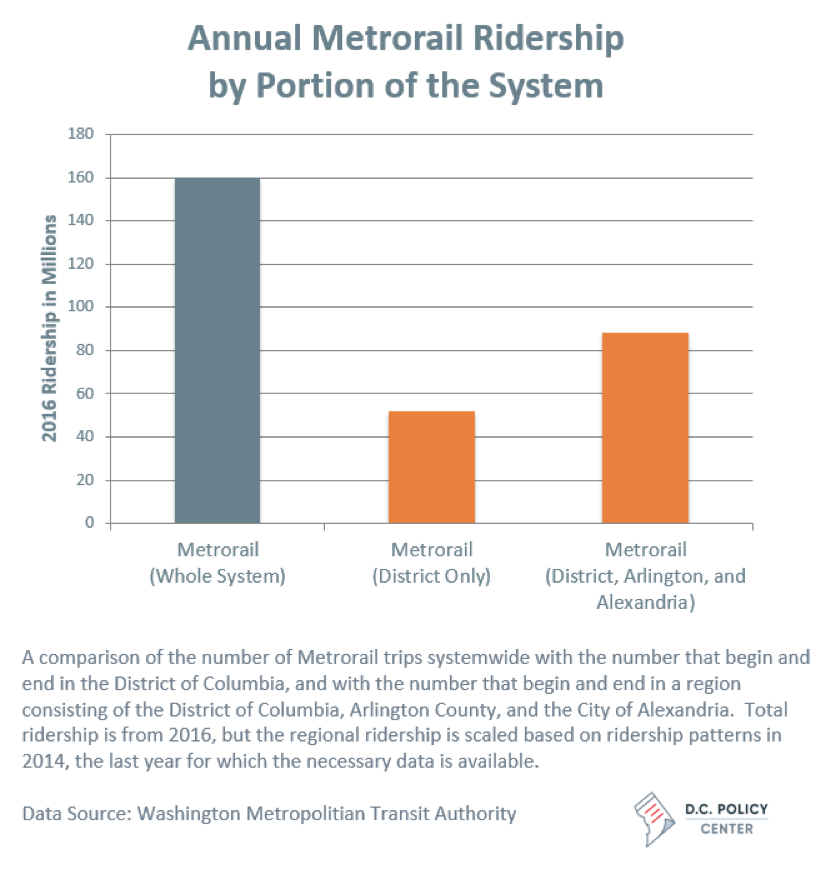

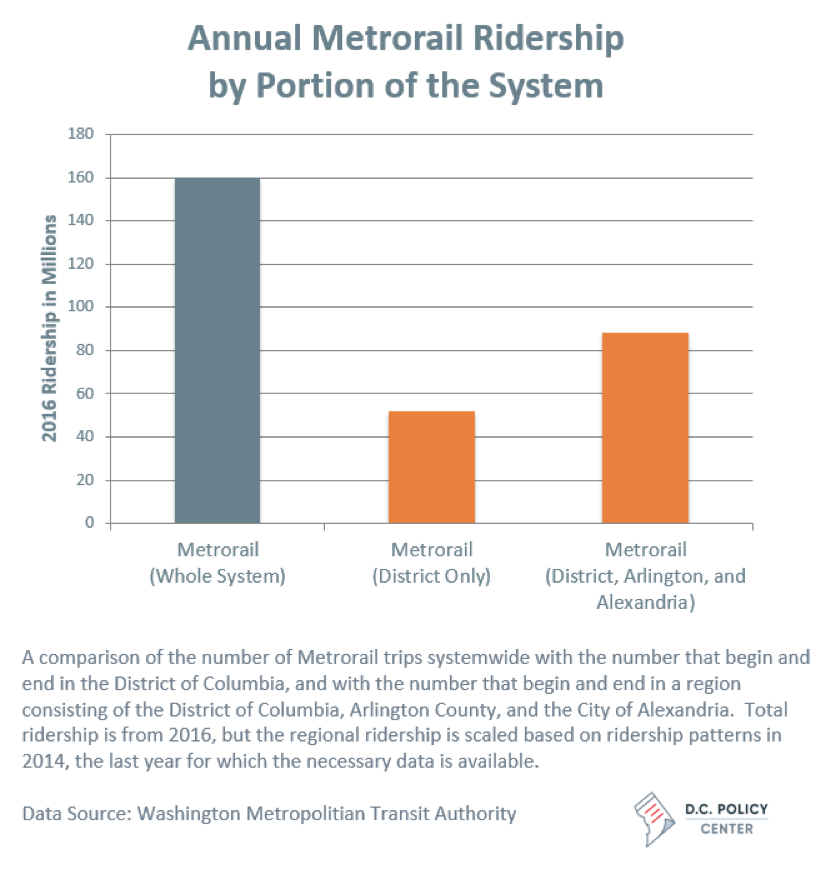

I found that, although Metrorail had 160 million riders in 2016, only about 52 million of these trips were entirely within the District. Rolling back the $0.25 fare increase scheduled for July 1 for trips within the District would cost about $13 million if there was no increase in ridership.

It seems unlikely that simply rolling back the fare increase (rather than actually lowering the fare from its previous level) would be enough to significantly increase ridership on its own, but if the system’s reliability increases after SafeTrack is complete, it’s likely that there will be some increase.

However, even if ridership within the District rebounded to its 2011 peak, the cost would only grow from $13 million to $16 million.

In comparison, the District’s total Metrorail operating subsidy in the fiscal year 2018 budget is $127 million, and its total contribution to WMATA operating funding (Metrorail, Metrobus, and Metro Access) for fiscal year 2018 is $370 million.

Could Arlington and Alexandria join in?

Since the inner suburban jurisdictions of Arlington County and the City of Alexandria are dense and have high per-capita Metrorail ridership, I decided to repeat my calculations for trips within a region consisting of the District, Arlington, and Alexandria.

I estimated that 88 million of Metrorail’s 160 million trips in 2016 were within this region, which means that a rolling back the $0.25 fare increase in these jurisdictions would cost about $22 million, in comparison to their combined Metrorail operating subsidy of $185 million and their combined WMATA operating funding of $478 million

Conclusion: D.C. could temporarily roll back the coming Metrorail fare increase for residents at a relatively low cost

Rolling back the $0.25 fare increase in the fiscal year 2018 budget for trips within the District—or trips within the District, Arlington, and Alexandria—is not a long-term solution to WMATA’s financial and ridership problems.

However, it would be a relatively easy way for the District government to make public transportation more affordable for District residents in the short term. Since it would likely increase Metrorail ridership—and thus fares paid—and since most of Metrorail’s costs do not depend steeply on ridership, it could even help the system’s overall financial health.

About the data

Because the Metrorail dataset I had available only showed entrances and exits during October 2014, two scale factors were necessary to estimate annual ridership at present-day rates.

First, since ridership is not even over the year—among other things, it is usually lower in summer—I used Metrorail’s monthly ridership data to determine that annual ridership in 2014 was about eleven times the October ridership.

Second, since ridership has fallen significantly over the past two years, I scaled down my ridership numbers by the ratio of October 2014 to October 2016 ridership.

In addition, I dealt with the ambiguous case of the three stations on the District boundary—Friendship Heights, Capitol Heights, and Southern Avenue—by treating them as entirely within the District. WMATA actually treats these stations as divided between jurisdictions when calculating each jurisdiction’s operating subsidy.