Executive Summary

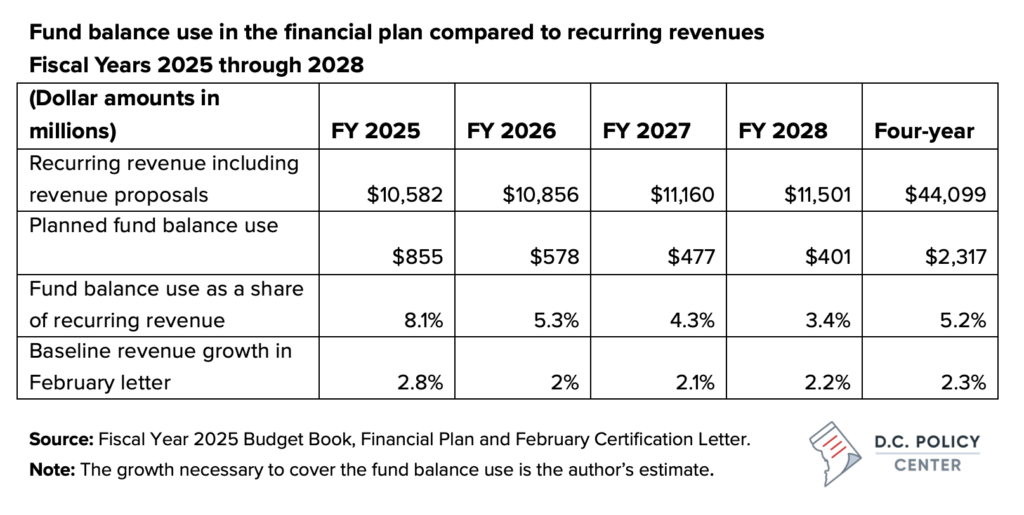

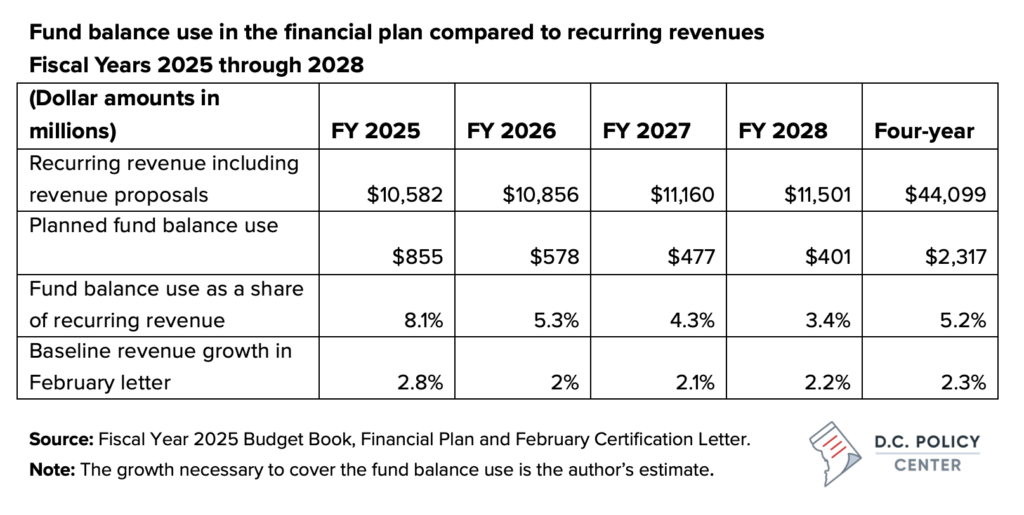

- Mayor Bowser’s proposed Fiscal Year 2025 budget and financial plan include both spending cuts and tax increases, but balancing the financial plan still requires $2.3 billion in fund balance use (past savings) over the next four fiscal years to close the gap between recurring expenditure and recurring revenue.

- The hard task for the District’s elected officials this budget season and in the coming years is to right-size the budget so annual revenue and spending are eventually aligned.

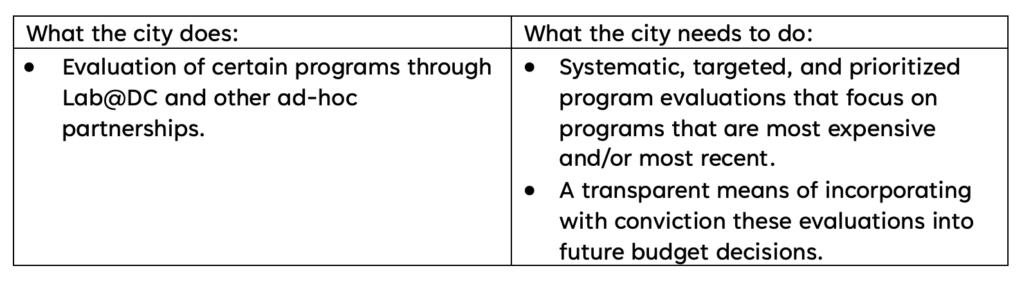

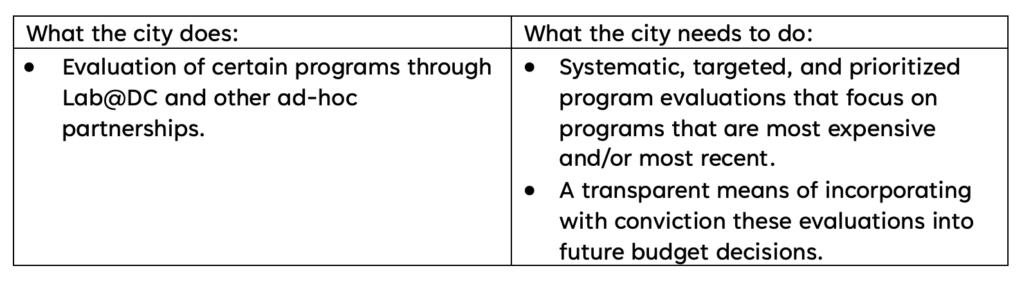

- In the short run, comprehensive evaluation of spending and those programs that grew significantly during (and after) the pandemic can help assess if these programs are meeting the needs as intended. D.C. already conducts sporadic program evaluations, but its track record in making budget decisions based on such evaluations is mixed.

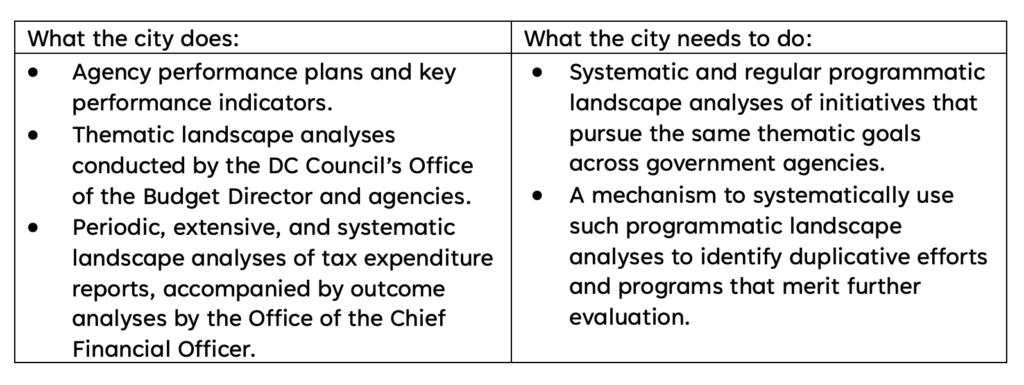

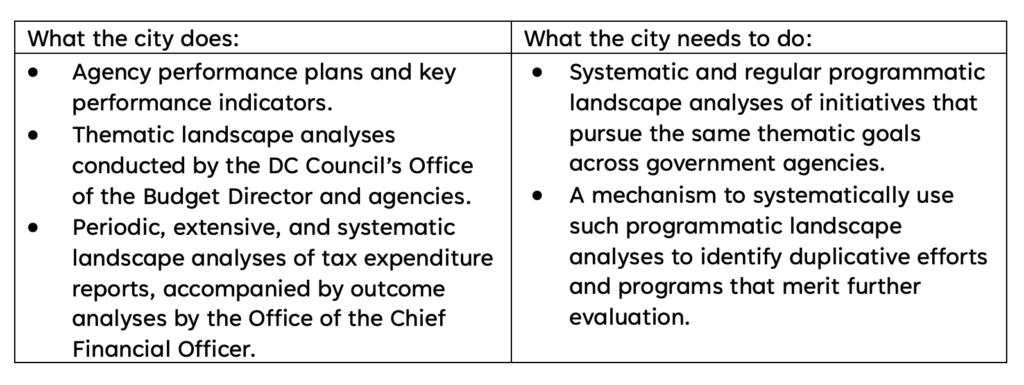

- In the intermediate term, thematic landscape analyses can help identify programs spread across multiple agencies but are serving similar needs. This type of analysis can help streamline the budget, or direct resources to programs that are most impactful. The District has some examples of such landscape analyses but, once again, their findings are not regularly considered in budgeting decisions.

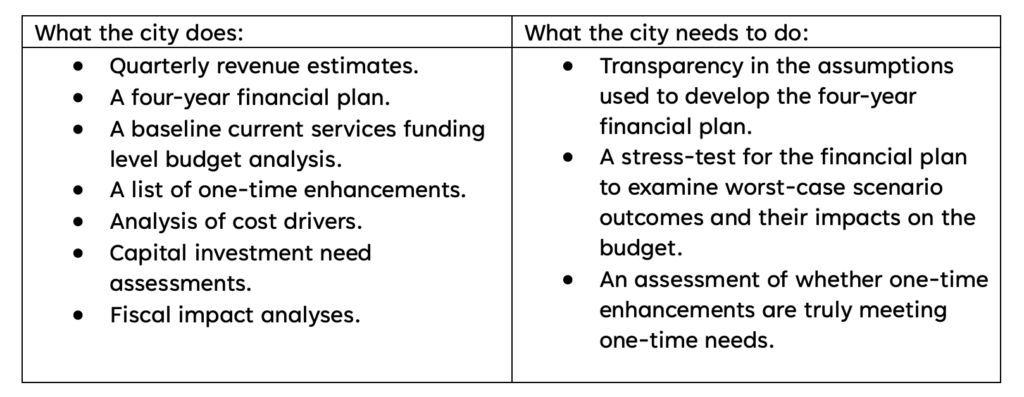

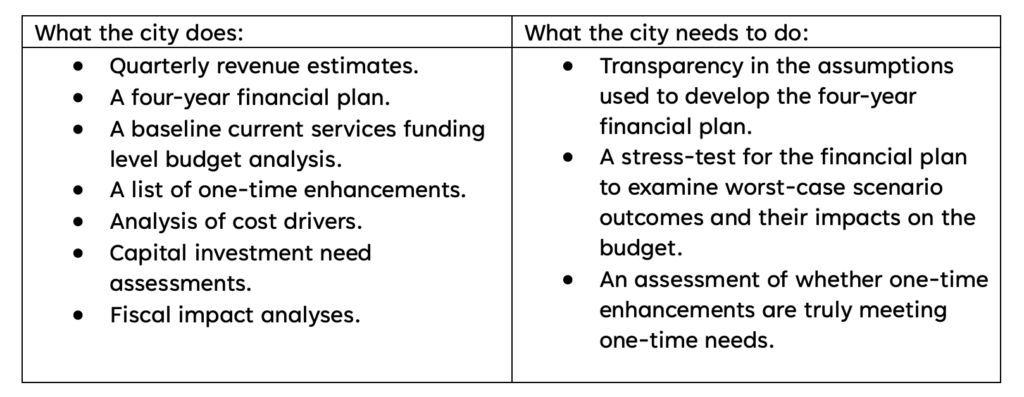

- The District has rigorous financial management practices, but the city can improve its financial resiliency by stress testing the assumptions used to develop its long-term budget projections.

- The city has the necessary foundation to build a resilient fiscal future, but it needs a dedicated effort to develop viable strategies to right size its budget and a commitment from city leaders to faithfully implement these strategies.

- This budget season, the elected officials should consider putting in place a formal commitment to completely close the gap between recurring expenditures and recurring revenues by Fiscal Year 2029.

- They should also consider standing up an Expenditure Commission early in the fiscal year to collect community and stakeholder feedback, conduct necessary analyses, and recommend budget actions that can help the city reach this critical goal.

Read the complete publication below or download a PDF copy.

Introduction

Mayor Bowser has submitted to the D.C. Council her budget proposal for Fiscal Year 2025 and the four-year financial plan period. The proposed budget represents a 7 percent growth in spending over the approved Fiscal Year 2024 budget,1 with significant investments in public safety and downtown recovery. It also substantially raises public school funding paid out of the local budget to make up for the federal fiscal aid schools will lose next fiscal year.2

Even with over $1.8 billion in new revenue initiatives, the four-year financial plan relies on drawing down $2.3 billion of fund balance.

To pay for expenditures, the proposed budget raises $328 million of new revenue in Fiscal Year 20253 ($1.8 billion through the financial plan period).4 But this new revenue is not enough to sustain the spending growth the city has experienced since the beginning of the pandemic, even with cuts to certain programs. As a result, the financial plan includes $2.3 billion of fund balance use (surpluses from past years in excess of required reserves)5 to pay for the proposed recurring expenditures—the equivalent of five percent of the planned spending.

It is worth pointing out that using one-time funds to balance the budget is not new practice. District Budgets approved prior to the pandemic often employed this strategy, but at a much smaller scale. For example, budget books for fiscal years 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020 show that fund balance use was typically about 1 percent of total spending planned for that financial plan period. The expectation was that the gap between recurring expenditures and recurring revenue would be eventually closed by higher than projected revenue growth. In other words, elected officials presumptively expected the revenue estimates to consistently be conservative and preemptively spent revenue that would later be certified. Hence, fund balance use was essentially “short-term borrowing” against future new revenue above the estimate.

Positive revenue surprises are unlikely to close the gap between recurring expenditures and recurring revenue.

Looking at the proposed financial plan, the scale of fund balance use can no longer be justified by presumptive revenue growth. For example, in the proposed Fiscal Year 2025 budget, the local budget spending is $855 million above the local recurring revenue, even after including the new revenue proposals.6 To close this gap, revenues would have to grow by 8.1 percent for the year. To compare, the projected growth for baseline revenue in the February revenue estimate is 2.8 percent—about a third as fast. Through the four-year financial plan period, revenues, on average, would have to grow by 5.2 percent to make up for the fund balance use. This is more than twice as fast as the projected average annual revenue growth through Fiscal Year 2028 in the February revenue letter (2.3 percent).

Any Council action that increases spending—regardless of how it is paid for—could make this structural problem worse.

Even with this difficult and sobering backdrop, the Council is considering restoring some of the cuts that are in the Mayor’s proposed budget. These include reinstituting the Pay Equity Fund that supplements childcare worker salaries ($70 million), restoring the Emergency Rental Assistance Program funding to last year’s level (approximately $30 million), setting aside funding for the SNAP program (could be as high as $40 million), just to name a few of the largest proposed cuts.

Councilmembers are understandably in a difficult position. If they restore these programs by cutting spending elsewhere, they would trade one unhappy constituency for another. But the underlying gap between recurring revenue and recurring expenditures would still be the same. If they restore these programs by raising new revenue (as was the case in fiscal year 2022), the underlying structural problem would still be there, at the very same scale, except with even higher tax burdens, and a corresponding negative impact on the city’s competitive position. And if they restore these programs by not replenishing the reserve funds,7 the underlying structural problem would be exacerbated by the amount of deferred reserves, and the city would have less cash in hand. This could necessitate going to bond markets to manage cash flow—something the city has not needed to do since Fiscal Year 20168—would diminish the city’s ability to nimbly take advantage of interest rate opportunities and could negatively impact the city’s bond ratings.

The city has strong financial management practices, but these can be improved to measure impact, increase efficiency, and assess risks.

The hard task for the District’s elected officials this budget season and in the coming years is to right size the budget so revenue and spending are eventually aligned. Despite all the pressures to restore programs that may lose funding, the Council, along with the Mayor and the Office of the Chief Financial Officer, can lay the foundation for a fiscally resilient future. These measures could include short-run targeted evaluations of post-pandemic programs that measure impact, longer-term interventions that identify duplicative programs to bring productive and allocative efficiencies, and systems-level changes that leverage the District’s current strengths in budgeting practices to better assess risks.

Measure # 1:

Short-term interventions: targeted evaluations of programs that were set up or significantly grew since the beginning of the pandemic.

The District’s spending grew by 36 percent between Fiscal Years 2019 and 2024 while local revenue grew by only 17 percent. Due to a $4.7 billion infusion from the federal government, and savings and surpluses from previous years, the city was able invest in new programs or expand existing programs to meet needs that emerged because of the pandemic. Some of the funding pressures in Fiscal Year 2025 are coming from these new or expanded programs that relied on one-time funding. The city would be served well by evaluating and examining the success of these programs to make sure that they are working as expected and meeting their intended goals.

One concrete example of such program evaluation is in public education.9 Since Fiscal Year 2021, the District invested approximately $34 million in High Impact Tutoring—an evidence-backed intervention to address pandemic-related learning losses.10 This program, from its very beginning, had an evaluation component (in partnership with Stanford University’s National Student Support Accelerator) to examine whether it is meeting its stated goals. While the full evaluation is not yet complete, preliminary results show that, at a minimum, students participating in High Impact Tutoring were less likely to be absent, and this impact was greatest for students who are chronically absent—a 7.3 percent reduction in the probability of being absent, which translates into a full week of schooling not missed. That finding is especially significant because chronic absenteeism remains a persistent problem in D.C., undermining investments the city makes in schools and learning. As a result, the Mayor has continued investments in this promising program in her proposed FY 2025 budget.11

As a starting point, the District could look at programs that were established or grew significantly post-pandemic to determine whether these programs should continue, continue with better defined targets, continue with changes in program design, or should be eliminated. For example, an evaluation of the Emergency Rental Assistance Program, which grew rapidly since the pandemic, can pinpoint how it fits with other housing assistance programs. An evaluation of the recently established Pay Equity Fund can help identify the conditions under which supplemental payments truly work in retaining childcare workers in the profession and incentivize them to pursue further credentialing.

These kinds of evaluations, in certain instances, already happen in D.C., and have, in the past, informed policy decisions. Lab@DC frequently partners with third-party researchers and other entitles to conduct evaluations of selected programs. For example, their work on absenteeism interventions showed that the Show Up, Stand Up program, which was designed to connect families of students who have 5 to 9 unexcused absences with various resources, was unsuccessful. This is because, as Lab@DC researchers found, many families were leery of these interventions because they associated them with child protective services. Further, this belief was not easily changed: a randomized trial showed that a letter sent to families from schools to explain the services did not change perceptions or increase participation. Perhaps, for this reason, the program has not been funded in Fiscal Year 2025.

Lab@DC, along with the Urban Institute, also examined the city’s flexible rent subsidies pilot, which offered families a $7,200 per year assistance for four years. The recipients were free to spend this money on rent or any other need. The results of the evaluation showed that participation in the program did not necessarily change outcomes regarding homelessness and the need for rapid rehousing (which was already low among the type of families that participated in the program), but significantly reduced the use of other publicly funded housing programs. These findings underscore the importance of evaluating housing assistance programs such as ERAP in conjunction with other interventions.

Similarly, Lab@DC’s research on scholarship incentives for early childhood educators through the DC LEAD program (along with Southeast Children’s Fund) revealed that money alone was not a sufficient incentive for further credentialing—an important finding that should shape the District’s Pay Equity Fund, if the D.C. Council chooses to restore all or part of its funding.

While some program evaluation is taking place, there is no systematic approach to program evaluations or a roadmap for determining what programs merit evaluation, and why. There is also no clear public understanding of how evaluations factor into policy decisions. The District can benefit from strengthening its current program evaluations, and prioritizing the examination of programs that could be most impactful, or are most expensive, or are designed to meet the most urgent or recent needs. (See the Appendix for elements of good evaluation programs)

Measure # 2:

Intermediate-term actions: programmatic landscape analyses

District agencies do develop performance plans and collect and report many performance metrics, but these tend to focus on agency processes, and not so much on program outcomes.12 Importantly, the city has multiple agencies serving similar constituents pursuing similar goals. Thematic landscape analyses can help identify potential duplications as well as opportunities for interagency collaboration so the District can provide the same services more efficiently.

For example, the research arm of the Council’s Office of the Budget Director has conducted landscape analysis on services for seniors to find 90 different publicly-funded programs serving the city’s approximately 83,600 seniors. But as far as one can tell, this resulted in no action to streamline these programs. The same office took stock of all commitments the District pledged toward subsidized affordable housing programs in Fiscal Year 2020, and found $840 million of operating expenditures (about 8.5 percent of the local fund budget that year) including funding for homeless services, housing finance, and direct assistance, again scattered across multiple agencies and programs. Again, no discussion on the efficacy of these programs followed. The Workforce Investment Council publishes an annual summary of all workforce development programs across all government agencies, with limited information on program outcomes. This effort could have led to better data sharing across agencies,13 but has not yet translated into a discernable systems-level changes in how the District offers workforce training programs.

Turning to the revenue side, the District has a stronger track record of landscape analyses. The Office of the Chief Financial Officer publishes a biennial tax expenditure report which assesses the cost of all tax exemptions, exclusions, adjustments, deductions, subtractions, credits, abatements, deferrals, rebates and special rules the District has adopted in pursuit of certain social goals. The most recent report shows that in Fiscal Year 2022, the District provided $189 million worth of tax breaks to support housing through its own laws, $400 million of tax breaks to support various social policies, $167 million to support education outcomes, and $99 million to increase income security. For many of these, the researchers provide comparative data or evidence from other localities on the success and effectives of the intervention. The researchers also periodically take deeper dives into certain areas (such as economic development or housing) and have published what they have learned from these closer examinations. But their findings only rarely turn into legislative action. In the intermediate term, the District could use programmatic landscape analyses to identify programs that are duplicative, counterproductive, and programs that may benefit from further evaluation. These types of analyses can help streamline spending or allow the city to provide the same level of supports at a lower cost.

Measure # 3:

System-level changes: Increased transparency in the four-year plan and budget stress tests

The District has rigorous financial management practices that set the city apart from other states and localities. For example, the city has quarterly revenue estimates that project revenues for a four-year period. Further, each budget must be presented with a four-year financial plan that is balanced and where available resources are shown to meet planned spending each year. The Office of the Chief Financial Officer also provides a baseline budget early in the budget process to inform stakeholders what resources are available, if at all, for enhancements, or what level of cuts must be made, if resources are not available. In addition, the Council’s Office of the Budget Director provides a list of one-time enhancements to inform the public on the programs that are funded only for one year. The Chief Financial Officer also prepares a long-range capital needs assessment to determine the amount of capital investment (and borrowing) necessary to keep the city’s infrastructure in good order. Finally, each bill considered by the Council receives a fiscal impact statement prepared by the Chief Financial Officer or the Council’s Office of the Budget Director that not only scores the cost of a legislative proposal (common in other jurisdictions), but also determines whether the city has sufficient money to pay for it (uncommon). While these are good practices, there are still other systems-level practices the city can adopt to identify risks early on and set expectations about future spending.

First, the city should be more transparent about the assumptions used to project future spending in the four-year financial plan. An examination of the financial plan for Fiscal Years 2025 through 2028 shows no growth in spending between Fiscal Years 2025 and 2026, and growth under 2 percent after Fiscal Year 2026. At a minimum, given current inflation expectations (As of April 2024, the ten-year inflation expectation is at 2.3 percent), a below-two percent growth expectation seems risky. Other factors that could impact spending and are hard to control are: interest rates (impacts debt service), health care costs (impacts fringe benefits and currently stands at 2.2 percent), growth in public school enrollment (automatically increases public education spending), growth in the number of at-risk students (automatically increases per pupil spending), other services that are automatically tied to the number of people eligible for the service (unemployment insurance, Medicaid spending, or correctional costs14), commitments that are hard to know and control such as the WMATA subsidy (the District has little control over WMATA financial management, and is on the hook for funding needs without much say on WMATA’s operations), or commitments that are somewhat under the District’s control but can pose risks, such as collective bargaining agreements,15 pension, and other retirement benefit contributions.

Second, and related, the city should stress-test its budgets and financial plans. Budget stress tests are commonly used in other states and have produced positive outcomes. Stress tests on the expenditure side could include sensitivity analyses around the assumptions used to develop the financial plan. Stress tests can also incorporate scenarios for economic downturns as well as District-specific worsening of economic conditions to gauge impact on both spending and revenue. The Office of the Chief Financial Officer has in the past presented alternative revenue scenarios for recessions or to capture specific risks (such as higher than projected office vacancy rates), but these scenario analyses are rare for the revenue side, and are completely absent from the expenditure side.

Third, the city needs a realistic, forthright examination of one-time enhancements to ensure that they are truly one-time. One-time enhancements included in the Fiscal Year 2025 budget add up to $353 million. Of this amount, $20 million are personnel expenditures, which are typically recurring, and therefore pose risk.16 There are other items that look more like continuing needs but only have one-time funding, including funding for snow removal equipment ($3 million), forensics testing ($3 million), and fleet management ($5 million). Other one-time enhancements include items that are legally discretionary but appear to meet continuous needs. These include subsidies such as $12 million for Emergency Rental Assistance, $1.9 million for youth homeless services, $30 million for rapid rehousing, $25 million for the non-profit hospital, $11 million for home purchase assistance, $11 million for safe passage, $9 million for mental health and rehabilitation services, $6.8 million for out-of-school time programs. The District has in fact provided these programs year after year, serving significant constituencies, and will again turn into budget pressures in next year’s budget.

The District needs the commitment of its elected officials to lay the foundation for a more resilient financial plan.

The District’s current fiscal picture is one with tepid revenue growth, extensive reliance on past savings to pay for spending over the four-year horizon, and an unknown future.17 [1] The city has the necessary tools, but it needs a dedicated effort to develop viable strategies to right-size its budget and a credible commitment from city leaders—the Executive, the Council, and the CFO—to implement these strategies.

As a first step, the District should give serious consideration18 to standing up an Expenditure Commission with representatives from the Executive, the Council, and the Office of the Chief Financial Officer to collect community and stakeholder feedback, conduct the necessary analyses, and recommend specific budget actions. This Commission should be given a clear fiscal goal and a specific timetable, so it has a clear roadmap.

Setting up an Expenditure Commission alone may not suffice. Experience from other states shows that collective action for cost controls requires a credible execution mechanism.19 To fix this problem, D.C.’s elected officials should commit to a specific timetable (for example by Fiscal Year 2029, which is the first year at the end of the current financial plan) to completely close the gap between recurring expenditures and recurring revenues.

Fiscal discipline is a necessary condition in order to maintain the District’s competitive edge. Intense fiscal turbulence may be four years away, but the city must lay the foundation for a fiscally resilient future now and build a roadmap for solving future budget woes, which are now wholly foreseeable.

APPENDIX – Elements of strong evaluation programs

An abundance of literature exists on best program evaluation practices. This literature covers a wide range of topics, including the investments governments must make for high-quality program evaluations, guidelines for selecting which programs to evaluate, and the standard elements of high-quality program evaluations. Below are some of the practical insights from the literature that the city can leverage and profitably draw on.

- To conduct high-quality program evaluations, the D.C. government will need to invest in people who possess the relevant expertise and analytical skills.

- Given that high quality program evaluations cost money, the D.C. government must be judicious in selecting which programs to evaluate. The D.C. government should develop a list of funded programs and review any existing evidence of each program’s effectiveness, and the effectiveness of similar programs in other jurisdictions. If there is a lack of existing evidence regarding a program’s effectiveness, the D.C. government should then review existing sources of data to use in a program evaluation.

- A strong program evaluation will recount a program’s purported goals and outcomes, and explain how the program is supposed to produce its intended outcomes. Those conducting the evaluation may find it beneficial to engage with the program’s stakeholders.

- A strong program evaluation will assess the degree to which the program is producing its intended outcomes or results. Given the possibility that a program’s results may be explained by factors unrelated to a program’s effectiveness, an evaluation will need a credible empirical strategy. Receiving feedback from outside experts can help ensure that the empirical strategy is a credible one.

- Performing a cost-benefit analysis as part of a program evaluation can help maximize the chance that taxpayer dollars are being put to effective and efficient use. A strong cost benefit analysis will spell out a baseline which a program’s costs will be measured against. Generally, a good starting baseline is an alternative world in which the program being evaluated does not exist. It may also be prudent for evaluators to consider multiple baselines before drawing a conclusion.

- To establish a reputation of independence and impartiality, evaluators should publicly outline their empirical strategy before conducting the evaluation. Such an announcement can help reduce the chances that an empirical strategy will be inappropriately chosen to reinforce predetermined conclusions. After completing the evaluation, evaluators should publicly release—to the extent possible—the data they used to conduct the evaluation.

Endnotes

- The Mayor is also proposing a revised budget for Fiscal Year 2024 that grows spending by an additional $506 million or a five percent increase over the approved budget.

- Sayin, Y. (2024). “Identifying what investments work as schools face difficult fiscal picture: testimony presented at the public meeting of the State Board of Education on April 17, 2024.” Available at https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/identifying-what-investments-work-as-schools-face-difficult-fiscal-picture/

- The baseline revenue for Fiscal Year 2025, before the proposed revenue initiatives, is $10.2 billion. Revenue initiatives include both new or higher taxes, and resources freed for general operating funds by the undoing of certain commitments to specific programs.

- The total new resources funding the general fund budget comprised of local funds, dedicated taxes, and special purpose revenue is $2.2 billion over the financial plan period.

- These include reserves required by federal statute, reserves required for debt service coverage, reserves required by local statute, and reserves set aside for future use.

- Not included in these numbers, but also supporting total spending are resources diverted from other recurring transfers such as transfers from TIF and PILOT accounts, including the Baseball Fund, which is coming to an end in Fiscal Year 2028, when the baseball bonds are defeased.

- DC Council Chairman Phil Mendelson April 19 2024 newsletter announced the Council’s intent to defer transfers to reserves to partially restore the Pay Equity Fund.

- This is the last year for which we could find an authorizing legislation for TRANs or Tax Revenue Anticipation Notes. Similar legislation was introduced for Fiscal Year 2020 but was not enacted.

- Despite significant investments, public schools have not achieved full academic recovery. Chronic absenteeism continues to be a major problem, and outcomes for high school students are particularly worrisome with increasing disconnect between promotion and graduation rates and other academic outcomes such as learning, SAT scores and post-secondary participation. Public schools are facing declining budgets in Fiscal Year 2025 and will need to identify what programs are most effective in meeting the needs. For details, See Sayin, Y. (2024). “Identifying what investments work as schools face difficult fiscal picture.” Testimony submitted to the State Board of Education. D.C. Policy Center. Available at https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/identifying-what-investments-work-as-schools-face-difficult-fiscal-picture/.

- For details on program design, see Coffin C. & J. Rubin (2022). “Landscape of High-Impact Tutoring in D.C.’s Public Schools.” D.C. Policy Center. Available at https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/dc-high-impact-tutoring/.

- Investments include $375,000 in the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education (DME)’s budget for “nudges” to improve attendance, $7.2 million for DC School Connect Program to provide school transportation for 350 student, and additional $7 million for the PASS and ACE truancy interventions programs to serve an estimated 680 youth. Coffin, C. (2024). “Education investments to boost attendance, improve learning, and strengthen high school in the FY25 budget need to also identify what works.” Testimony provided before the DC Council Committee of the Whole on April 4, 2024. Available at https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/education-investments-to-boost-attendance-improve-learning-and-strengthen-high-school-in-the-fy25-budget-need-to-also-identify-what-works.

- Often, there are too many metrics, especially for larger agencies, making it difficult to ascertain agency priorities and performance benchmarks that shape budget decisions.

- See the Recommendations section of the Accompanying Document to the FY 2022 Expenditure Guide, available at https://dcworks.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/DCWorks/publication/attachments/FY22%20Accompanying%20Document_3.1.2023.pdf.

- Identified as a potential risk in the FY 2025 budget.

- For example, the Washington Teacher Union’s contract the city signed in October of 2023 was one of the most significant cost drivers. And that contract was backward looking, covering a period between 2019 and 2023. In addition to the WTU contract, the city has several other collective bargaining agreements it needs to renegotiate in the coming years, and a proposed $103 million budgeted in the Workforce Investment Fund in Fiscal Year 2025 to pay them.

- This is also presented as a potential risk in the CFO’s certification letter.

- To restate the problem, current projections show that the gap between recurring expenditures and recurring spending narrows down from $855M to $401M from Fiscal Year 2025 to Fiscal Year 2028. But this assumes all one-time spending of $363M in FY 2025 is eliminated (as discussed, a risky assumption), and spending growth is strictly controlled in order to remain below the tepid revenue growth) to save another $101 million (another risky assumption), only to end up with a 3.4 percent gap between uses and sources.

- The District has tried this before: in 2019, the Council adopted legislation to form an Expenditure Commission to analyze spending patterns, identify inefficiencies, and make recommendations. The Commission suffered a slow start and eventually the idea was discarded when the COVID-19 pandemic began.

- For example, in 2021, Alaska’s legislators put together a bipartisan Fiscal Policy Working Group to examine the long-term trajectory of the state’s budget and make recommendations to achieve a balanced budget. The Group made several recommendations including revenue policy changes and budget cuts, but its work was never implemented. For details, see the final report of the Working group available at https://akleg.gov/docs/pdf/2021_Fiscal_Policy_Working_Group-Final_Report.pdf as well as an overall analyses of Alaska’s fiscal woes available at https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2023/11/alaska-tools-for-sustainable-state-budgeting.