Naloxone saves lives, but it’s only the first step.

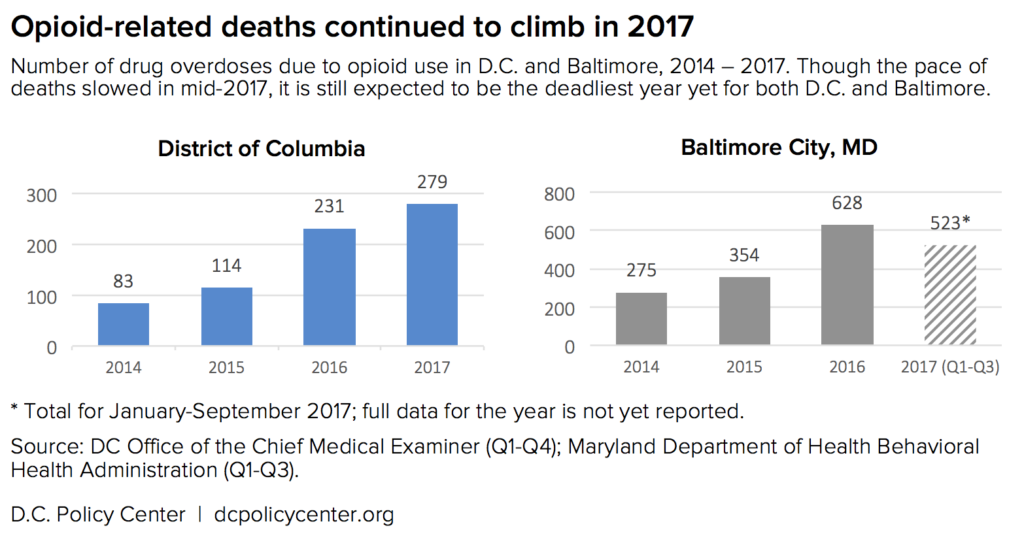

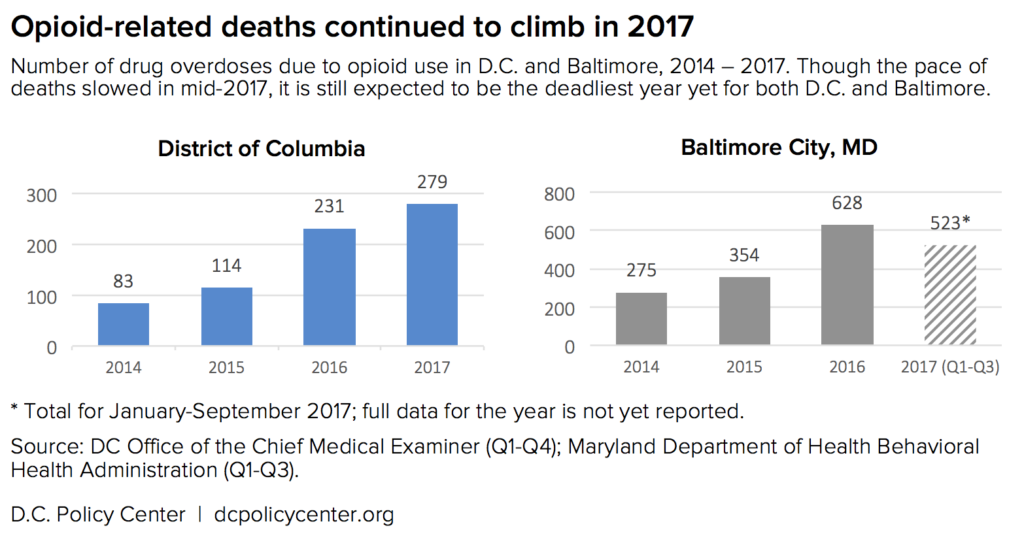

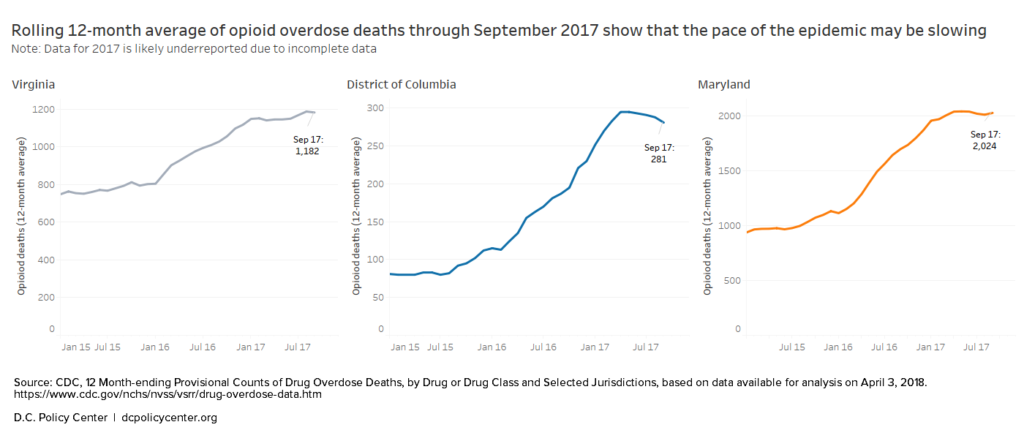

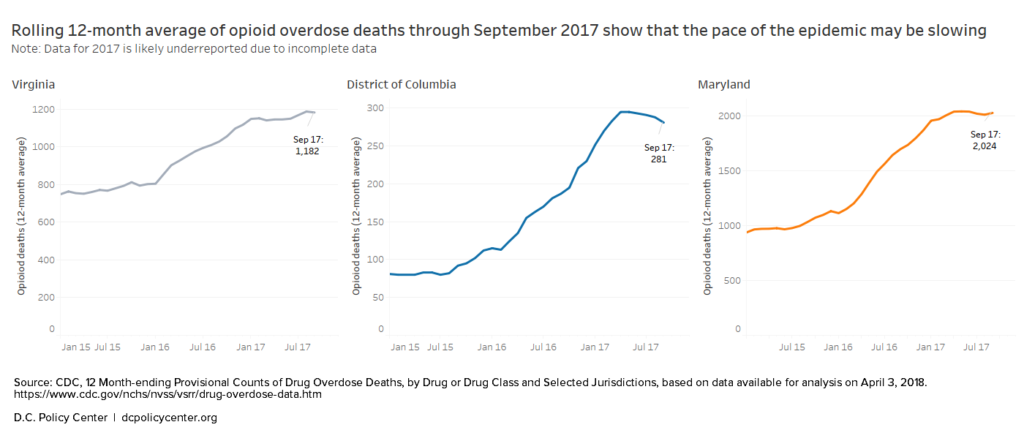

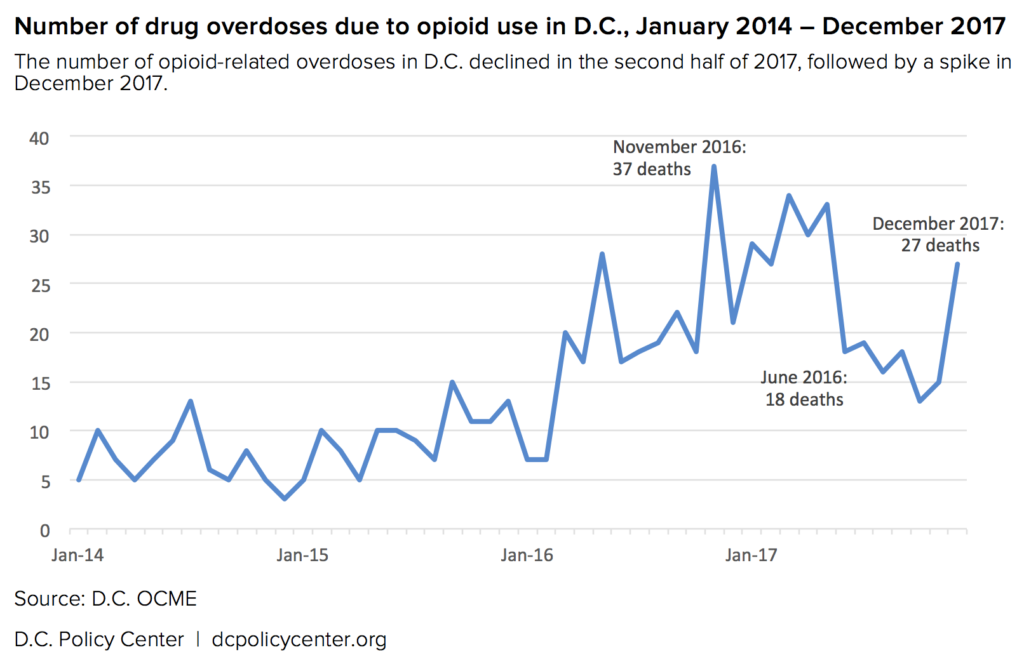

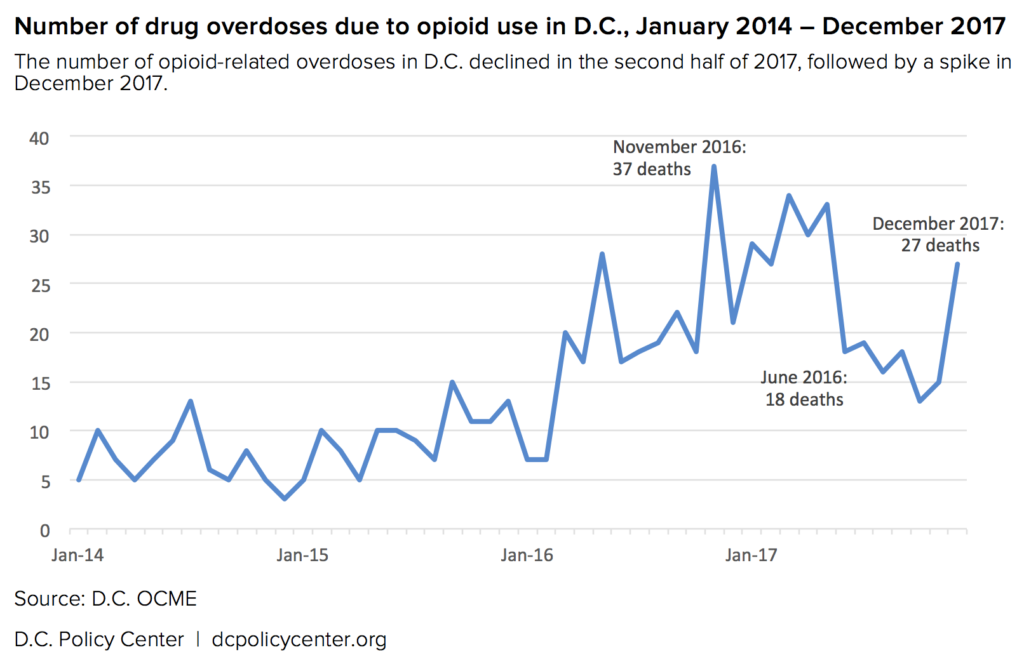

The number of Americans who have died in the ongoing opioid epidemic continues to climb. Between September 2016 and September 2017, more than 45,600 Americans died from overdoses involving opioids. The number of fatal opioid-related overdoses in D.C. more than doubled between 2015 and 2016, and continued to rise in 2017. While Baltimore has not yet published its final numbers for the previous year, preliminary data for the first three quarters of 2017 suggests a similar trend.[1]

Opioids are sold and used in many forms, including opium-derived medications like morphine and codeine, synthetic drugs like fentanyl and carfentanil, prescription painkillers like OxyContin, and street drugs like heroin. The shape and trajectory of the opioid epidemic has also varied across the country. While the initial stages of the current crisis were seen as a largely rural problem involving prescription opioids, recent years have seen increasing death rates in urban areas. In cities like D.C. and Baltimore, deaths have surged among older heroin users due to the introduction of the synthetic opioid fentanyl, a story the D.C. Policy Center covered in February.

With limited and sometimes conflicting responses at the national level, policymakers and the public health community in the D.C. region have been on the front lines of addressing the rising number of opioid overdose deaths. The D.C. Policy Center spoke with health officials, first responders, service providers, and researchers throughout Maryland and the District of Columbia to learn what the region is doing to mitigate the worst effects of the epidemic—and what should come next.

As the number of fatal overdoses continues to rise, the immediate response in D.C. and Maryland has been to expand access to naloxone, a medication that reverses overdoses. Naloxone, also known as Narcan, is safe and easy to use, and is widely used by first responders in the area; officials and practitioners are now focusing their efforts on expanding naloxone use among residents, who may be most able to respond quickly the overdose of a friend or family member.

The larger component of the local response involves expanding access to health care and treatment options, so that fewer people will experience an overdose in the first place. But a number of barriers remain—including restrictions from the federal government and insurers and lingering public antipathy toward the victims of the crisis. The good news, however, is that there is strong research to support public health approaches, and local officials have begun to find some degree of success—and even sound a cautious note of optimism.

“In Maryland, I am seeing the system of coordination begin to mature and to begin to work,” says Clay Stamp, Executive Director of the Opioid Operational Command Center in the Maryland Governor’s office. “We’re making headway on stigma, our programs are starting to work, we’re communicating. We just need to keep our nose on the grindstone and do the hard work.”

Ending the opioid crisis will require sustained action at the local, state, and national level. Stakeholders throughout the region emphasize that the solutions are in reach; the challenge now is to find the social and political will to scale them up.

I. Naloxone: The opioid-reversing medication saving lives at the front lines of the opioid epidemic

U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams recently issued an advisory urging more Americans to carry naloxone, a drug capable of reversing an opioid overdose. “We should think of naloxone like an EpiPen or CPR,” he says. While naloxone (also known by the brand name Narcan) is not a new tool[2] in the fight against opioid overdoses, it has become more widely used in recent years as policymakers have sought to combat the rising death toll of the epidemic.

High doses of opioids slow the central nervous system, and during an overdose, a person’s breathing may slow or even stop. Naloxone is what’s known as an opioid antagonist, and works by knocking the opioid molecules off their receptors inside the brain, which allows the person’s breathing to return to normal. “It’s pretty miraculous,” says Alan Butsch, Battalion Chief of Emergency Medical Services for Montgomery County Fire and Rescue. “The patient usually wakes up or at least starts breathing.”

Naloxone comes in the form of an injection, an auto-injection, or a nasal spray; the nasal spray, marketed primarily under the brand name Narcan, is the most accessible version, and typically costs about $150 for a pack of two without insurance.

Naloxone is generally safe and easy to use, with few side effects. It also won’t cause harm if accidentally administered to a person who has not taken any opioids—in fact, it’s long been standard protocol for paramedics to administer the drug to any patient who is unresponsive and in respiratory distress. For someone who has developed a physiological dependence to opioids, however, naloxone can cause immediate withdrawal—a deeply unpleasant experience. Due to the pain of withdrawal and the risk of the naloxone wearing off before the opioids lose their effect,[3] people who receive naloxone should still seek emergency medical attention after being revived.

The CDC reports that between 1996 and 2014, at least 26,500 opioid overdoses in the U.S. were reversed by laypeople administering naloxone, a figure that does not count administrations by first responders and emergency rooms. However, as the necessity of naloxone has increased in recent years, so has its price. Last fall, NPR reported that the price D.C. first responders pay climbed from $6 in 2010 to $30 in 2017; the D.C. Fire and Emergency Medical Services Department spent $170,000 on naloxone in ten months. In Baltimore, Commissioner of Health Dr. Leana Wen told NPR that price increases have forced the city to ration access to the drug.[4]

How naloxone is used in the D.C. area

The D.C. government has made significant efforts to expand the availability of naloxone over the last few years. Between May 2016 and June 2017, Mayor Bowser’s office reports, District-purchased naloxone kits were used to save at least 290 lives. (For context, the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) recorded 231 opioid-related deaths in 2016 and 279 in 2017.) In 2018, the D.C. Department of Health reports that 129 overdoses have been successfully reversed so far.

“If we keep them breathing, we can keep them alive long enough to get treatment,” says Dr. Neha Sullivan, Assistant Medical Director at D.C. Fire and Emergency Medical Services (FEMS). The Mayor’s office also announced plans to distribute another 2,500 naloxone kits to the community and allocated a $2 million federal grant to support medically-assisted treatment and other public health and rehabilitation strategies.

In Maryland, officials have also worked to expand naloxone access and prevent overdoses. In October 2015, the Maryland legislature passed a bill to broaden prescribing authority, and the need for a prescription was lifted entirely in June 2017—making the drug available to anyone at all Maryland pharmacies. Beginning this school year, every Maryland school is required to keep a supply of naloxone on hand.[5]

In the Maryland Governor’s office, Stamp reports that emergency medical services administered naloxone 14,441 times in 2017, with friends or family also providing the drug an estimated 500 times prior to EMS arrival.[6]

In Baltimore, which recorded 628 of Maryland’s total 1,856 opioid-related deaths in 2016, Dr. Wen says, “We have seen that naloxone saves lives.” In October 2015, Dr. Wen issued a blanket prescription to every resident of the city, and since then Baltimore residents have used the drug to save at least 1,785 lives. “We should be doing everything we can to increase access to treatment,” she says, “but at the same time we should be increasing access to naloxone.”

Stakeholders throughout the region also emphasize that naloxone, alone, won’t solve the crisis. Like a defibrillator, the fundamental purpose of naloxone is to save a life—a crucial tool, but one that can’t cure the underlying condition. “We have to save a life today for there to be any hope for tomorrow,” says Dr. Wen.

Dr. Susan Sherman, a professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Medicine and the principal investigator of the recent FORECAST study “Fighting Fentanyl,” warns that naloxone, like many harm reduction tools, is not a magic bullet. “People want to understandably focus on how to get people to stop drug use,” Dr. Sherman says, “and that’s not where people who use drugs necessarily are.”[7]

All of the officials interviewed stressed the need to expand treatment programs. “Narcan is a pretty powerful band-aid, but it’s just a band-aid,” says Butsch of Montgomery County Fire and Rescue. “If we really want to solve this problem, we need to make available treatment options for both opiate addiction and for behavioral health.”

Debates over naloxone use illustrate deeper divides in how we view the nature of opioid addiction

While public health officials work to increase naloxone access, critics have argued that expanded access could worsen the crisis by encouraging drug users to engage in more reckless behaviors. The controversy around naloxone flared up in early March following the release of a working paper by economists Jennifer Doleac and Anita Mukherjee on the “Moral Hazard of Lifesaving Innovations.” Doleac and Mukherjee posit that harm reduction tools like naloxone present a “moral hazard” by essentially insuring drug users against risk, encouraging them increase their consumption or seek out more powerful drugs like fentanyl. The paper’s thesis touched an immediate nerve within the treatment community, and public health experts soon raised doubts about its approach and underlying methods.[8]

One reason the public health community reacted so strongly to the moral hazard paper is that similar reasoning has led to calls to limit the number of times a person can be administered naloxone. Concerned about the potential political ramifications, Dr. Wen says, “to me this is the equivalent of someone who is dying of a peanut allergy. You don’t say, well I’m not going to give you an EpiPen because it might make you eat peanuts next time. We don’t deny [treatment] for any other illness.”

This debate comes at a delicate time in the opioid crisis: a recent AP poll shows that stigma remains widespread, with the country almost evenly divided on the question of whether addiction represents a medical problem or a moral failure. While researchers and practitioners emphasize that opioid use disorders should be viewed (and treated) from a public health lens, some policymakers want to address it as a criminal matter and hold individual users to account.

In Maryland, Del. Andrew Cassilly (R) recently introduced a bill that would essentially criminalize a drug overdose by requiring first responders to issue a citation to any individual requiring naloxone three times within a given period and then force that person to detox in a 30 day civil commitment. In the Baltimore Sun, Del. Cassilly argued, “keeping someone alive should not be confused with saving a person’s life. Many addicts are now using Narcan, funded by taxpayers, as a safety net while they continue to abuse these drugs.”

Public health officials and medical providers say that this is the wrong approach. “I understand that the sentiment is to try to push people toward treatment and to hold them a little bit more accountable,” says Dr. Raymond Crowel, Chief of Montgomery County Behavioral Health & Crisis Services, “but any path that leads to jail is a criminalization of an addiction.”

If there’s a moral dimension to providing naloxone, it should be keeping people alive, argues Dr. Crowel. With programs being rolled out across Maryland, he contends, “people are surviving longer, [and it] gives us a chance to get them into treatment. And so, that for us is the calculus.” In Governor Hogan’s office, Clay Stamp echoes that sentiment. “We have to continue to grow the elements and we have to build the ladders to connect them,” he says, but the system is “beginning to work.”

In his recent call for more Americans to carry naloxone, U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams said, “When a person is having multiple overdoses, I see that as a system failure. We know addiction is a chronic disease, much like diabetes or hypertension, and we need to treat it the same way.” In practice, treating addiction as a chronic disease means developing a robust public health system that provides a range of treatment services and actively channels users toward those opportunities.

II. After reversing an overdose, providing multiple paths to accessible and affordable treatment options

Naloxone administration by first responders may seem to be a natural entry point to channel people toward treatment, but experts say that’s rarely the case. Even if a near-fatal overdose does serve as wake-up call for an individual, the first responders, emergency departments, and public safety officers who might have administered the naloxone are rarely equipped to provide the kind of long-term resources that patients struggling with addition need.

Dr. Wen wants to change that by making it easier for people who experience an overdose to connect with a robust and affordable treatment system. “When somebody comes in who requires a naloxone administration,” she says, “they need to have access to on-demand treatment that’s offered to them, that’s available, that’s convenient in their community, that’s affordable.”

At the state level, Stamp concurs, “The key piece is building our infrastructure to meet their needs so that when they are ready to say ‘I need help,’ that it’s there.” To that end, Maryland rolled out a number of initiatives in 2017, including the creation of the Opioid Operational Command Center to coordinate response efforts across state agencies. Stamp, who serves as Executive Director, is an emergency manager by training and preaches the importance of a balanced approach. But for now, he says, the emphasis has been mostly on treatment. “I’d say if you’re going to rank it, it would be number one treatment, number two prevention, and number three enforcement.”

The Baltimore City Health Department, with support from city and state partners, also recently opened the state’s first Crisis Stabilization Center at Tuerk House, a treatment center with deep roots in the community. At the center, patients struggling with addiction will have immediate, round-the-clock access to a range of services and professionals and will receive sustained follow-up case management to connect them with behavioral health services. The intention is to roll out similar outreach centers to hot spots throughout the state.

Along those same lines, Maryland has also expanded a program dubbed SBIRT (for Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment) that trains public service providers to screen for potential drug and alcohol abuse and actively works to connect at-risk individuals with peer recovery specialists and refer them to available treatment services. Initially located primarily in hospitals, the program has since been expanded to include a number of detention centers, schools, and additional health care providers. “We see this as a priority strategic effort for the state to work with our local jurisdictions,” says Stamp.

The key is that treatment—both for addiction and other mental health problems—needs to be available when and where patients need it. The system also needs to provide multiple points of contact leading to convenient and voluntary treatment programs.

Officials also say that better data-sharing between local and state agencies will also create a more nimble public health response. In Montgomery County, Dr. Crowel describes how data exchange between fire and rescue, emergency departments, and behavioral health services can improve community outreach. He cites the example of “a person who overdosed and was in an [emergency department] on a Friday, got out on a Sunday, and overdosed on a Tuesday. The ability to share that information … means that my team can now reach out to that person” and match them with an appropriate treatment program. Maryland recently passed a bill to establish these kind of data-exchanges (or opioid intervention teams) state-wide.

The D.C. region is working to expand treatment options, but challenges remain

The creation of various overlapping outreach and intervention systems is a positive step in fighting the region’s opioid epidemic, but it means little if the demand for treatment continues to outstrip capacity. And unfortunately, that appears to be the case: both nationally and in the D.C. area, treatment is rarely available to people when they need it most.

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is proven to be one of the most effective therapies for drug addiction—particularly when paired with follow-up counseling. Most people have heard of methadone treatment, in which patients visit a clinic every day to receive a specific dose of methadone to prevent withdrawal symptoms. Naltrexone (or Vivitrol) is another medication that can be used in MAT; like naloxone, it’s an opioid antagonist that blocks the effects of other opioids, and is available as a daily pill or monthly injection.

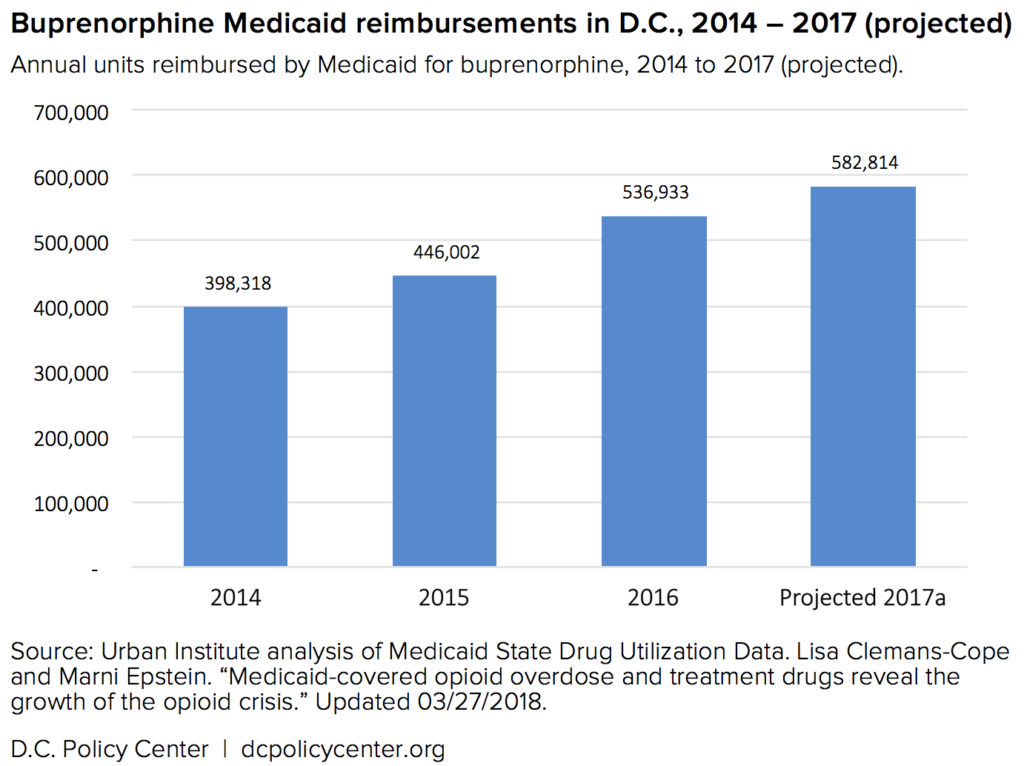

The most promising and commonly used medication is buprenorphine. As with methadone, buprenorphine has some euphoric effects but generally has fewer side effects and a lower potential for misuse. Many brands, like Suboxone, include a low level of naloxone to discourage additional opioid consumption. As a recent article in the Atlantic described, France was able to reduce overdose deaths by 79 percent within four years during a 1990s-era heroin epidemic primarily by expanding access to buprenorphine.

Maryland has been working “feverishly” to expand treatment Stamp says, “but the trouble is it’s not a light switch you flip on.” One breakthrough has been to expand Medicaid reimbursement for drug treatment programs, a move that has increased the number of patients accepted into residential care, as well as outpatient counseling and MAT. “It’s just a game changer,” says Stamp.

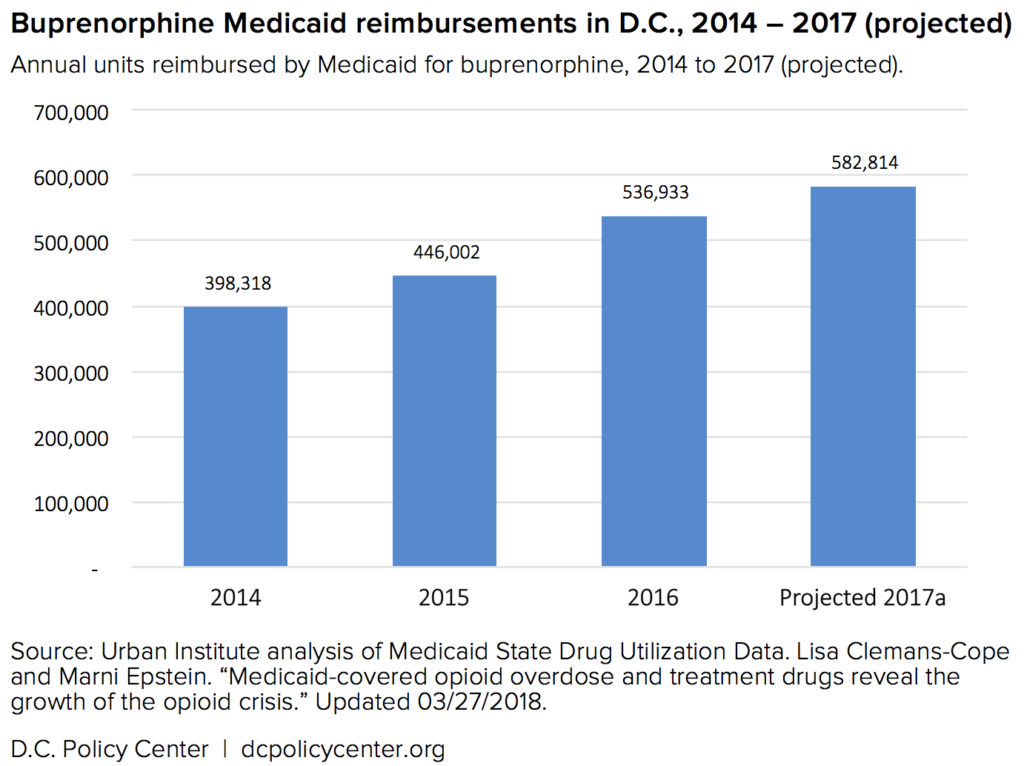

Michael Kharfen, Senior Deputy Director of HASTA (HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STD & TB Administration) at D.C.’s Department of Health, notes that buprenorphine is especially promising for long-term opioid users who may have already tried methadone or other traditional treatment options. Unlike methadone, buprenorphine is considered safe enough to be prescribed by a doctor and taken at home, making it much easier to access—if people can get a prescription.

Part of the scarcity of treatment is created by the federal government. Providers are currently limited to treating only 30 patients with buprenorphine in their first year and 100 in their second; since 2016, some are able to receive a waiver to treat up to 275. And while the 2016 Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) allowed a wider range of health care providers to prescribe the drug, they still must receive significant training to do so—eight hours of training for medical doctors, and 24 hours of training for nurse practitioners and physicians assistants.

Kharfen believes that federal requirements are restricting access unnecessarily. “Would you say: ‘I can only treat so many people with diabetes?’” he asks, “Would you say: ‘I can only treat so many people with cardiovascular disease?’” Such constraints limit the opportunities available for people who are ready to seek treatment. Dr. Randi Abramson, Chief Medical Officer at the D.C. nonprofit Bread for the City, likewise supports greater access to buprenorphine-based MAT. “People want to do the right thing,” she says, and shouldn’t face unnecessary barriers. “If medication is important, give people access to medication.”

At JHU, Dr. Sherman points out that, despite CDC prescription guidelines, there are no federal limits on the number of patients who can be offered actual opioids like OxyContin. This, in fact, has become a major flash point as doctors and chronic pain patients have pushed back strongly against state-level efforts to limit opioid prescriptions. By early April 2018, 28 states had some kind of limit on initial opioid prescriptions, usually a maximum supply of one to two weeks. Access to legal drugs—whether naloxone, opioids, or buprenorphine—is shaping up to be one of the major battlegrounds on which the future of the crisis will be decided.

In the meantime, D.C. is doing what it can within those federal constraints to increase the number of providers who can offer buprenorphine. Noting that nurse practitioners and physician assistants tend to spend the most time with patients in many health centers, Kharfen reports that D.C. has begun to compensate practitioners at five Federally Qualified Health Centers[9] for the time it takes to complete the training. He says that D.C. Medicaid[10] is also attempting to remove the existing requirement to receive prior authorization for every buprenorphine prescription, another common barrier to treatment.

The District is also trying to apply some of the lessons learned in Maryland around helping providers in hospitals and other settings connect patients at risk for opioid addiction with treatment and other resources. Kharfen says that one exception to federal buprenorphine restrictions is emergency departments. Based on models in Baltimore, New Haven, and elsewhere, Kharfen says, the District is planning a pilot program with some area hospitals to begin patients in the emergency room, “and then making a very quick connection to one of our community providers of buprenorphine to sustain that person on treatment.”

Ultimately, area officials and practitioners emphasize that the region needs to provide a variety of treatment options. “We need to fill the toolbox for our physicians,” says Stamp.

Health experts also stressed the need to better integrate harm reduction and treatment into primary care. Most of the District’s naloxone supply, for example, has been distributed through community health centers rather than individual providers. D.C. has a strong primary care system, but Dr. Abramson points out that it’s unusual for primary care physicians to give out clean needles or distribute overdose kits.[11] “We’ve let people down,” she says.

Much like naloxone, MAT remains subject to public controversy due to the perception that such treatments are simply “substituting one opioid for another.” But that, too, is a product of stigma and a moral view of addiction; health experts point out that we don’t see physical dependence on a medication as inherently problematic for other medical conditions. In Baltimore, Dr. Wen says, “We don’t say to somebody with high blood pressure, ‘Why are you still on blood pressure medications? You’ve been on it for a month, now it’s time for you to stop.’’

Erasing the stigma of addiction will require a broader social and cultural shift. For now, the bottom line remains that treatment must be easier to access than street drugs. The drug crisis will continue until the public sector designs and installs a system that can match the ease and convenience of the illicit drug market.

Addressing the opioid epidemic requires immediate and sustained action at the local, state, and national level

Even as state and local officials in the D.C. area are working to bring an evidence-based public health approach to the opioid crisis, there are conflicting messages at the national level. Despite the declaration of a public health emergency in October 2017, the White House has preferred to treat the opioid epidemic as a criminal justice and law enforcement issue. In his most recent remarks on the subject, President Trump mostly spoke about the need to “get tough” with drug offenders and even raised the prospect of executing drug dealers, a punitive policy Attorney General Jeff Sessions quickly endorsed.

Congress allocated roughly $4 billion in new public health funding to address the opioid crisis in the latest spending bill, but it’s unclear exactly how that money will be spent. Whether national policy will take the form of a concerted public health campaign or the cultural politics of the war on drugs remains to be seen.

These mixed signals at the national level make the regional response all the more critical. Across the country, state and local governments are implementing bold and innovative public health strategies, like safe consumption sites, offering inexpensive tests to check for fentanyl, needle-exchange programs, criminal justice reforms, the legalization of cannabis, and dynamic data-exchange initiatives. “There are lots of pockets of things going on around the country that we just don’t know about and don’t hear about,” says Dr. Crowel.

Examples from other countries suggest an even wider range of potential measures: Zurich, for example, has had extraordinary success from focusing on therapy and treatment, an approach that includes expanding access to both methadone and prescription heroin. The bottom line is that there are many approaches for jurisdictions to draw from, often with decades of evidence behind them—and we will need as many as possible to truly address the ongoing epidemic.

What does a comprehensive approach look like? Evidence from around the region suggests several components. First, we should limit the immediate harm from drug use through widespread evidence-based programs like needle exchanges, safe consumption sites, and access to naloxone. Next, people experiencing opioid addiction must have access to convenient, affordable treatment options, likely including some form of medication (such as buprenorphine) and behavioral health support—as well as access to stable housing and comprehensive health services.

Better coordination will be critical. Agencies from the local to the national level should collect and share data as quickly as possible to identify trends, mobilize resources, and target intervention. In addition to law enforcement and interdiction, one of the biggest things the federal government can do is to simplify funding streams. A major problem encountered at the state level, says Stamp, is that even when Congress is willing to spend on public health initiatives, the funds are distributed through the executive branch “like a sprinkler. It’s coming from every different agency, and it makes it very difficult.” A unified funding stream from the national government would speed the local response and therefore save lives.

Congress also needs to reduce the barriers faced by health care providers in prescribing treatment medications, and public and private insurers can make it easier for patients to access the types of treatment that work for them. In the long run, addressing the underlying drivers of opioid use disorder by improving access to physical and mental health care will be critical to inoculating against the future spread of addiction—as will the development of sophisticated prevention programs that go beyond the ineffective scare tactics and abstinence-only messaging of years past.

But the larger impediment at the root of these legislative roadblocks is social and cultural. Stigma continues to slow the implementation of public health strategies and allows for continued inaction by the national government. Meanwhile, the country must also face the deeper crisis of which the opioid epidemic may only be a symptom. In Baltimore, Dr. Wen says, “We need to look at why is it that we have so many people using prescription opioids and heroin in the country.” While physical pain can play a part, she says, “there is something else people are treating . . . We don’t want people’s lives to be something that they want to escape from.”

There are signs, however, that the speed of the epidemic may be slowing. After an alarming climb in 2016, the overdose rates for D.C., Maryland, and Virginia’s overdose rates appear to have leveled off in mid-2017. Full data hasn’t yet been reported for the last quarter of the year, and local officials are cautious in their interpretation of recent trends. Michael Kharfen at D.C.’s Department of Health says that while the stretch of lower overdose levels in late 2017 has been “somewhat encouraging,” there’s still much that officials don’t know about the dynamics of opioid use and overdose, making it difficult to identify a trend in the moment.

Those unknowns present a major challenge to local officials, and the opioid epidemic continues to pose a profound—if not entirely unprecedented—threat to American public health. The current phase of the regional crisis was driven by the arrival of powerful and inexpensive synthetics like fentanyl in the local heroin supply. In the last year, health officials in D.C. and Maryland have seen an increase in overdoses associated with yet another synthetic opioid, carfentanil. While fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine, carfentanil can be 100 times stronger still, or 10,000 times stronger than morphine. Maryland recorded at least 57 carfentanil-related deaths in 2017, and the drug has also begun to show up in toxicology screens of overdoses in D.C. and Virginia.

In the coming weeks, as Congress debates a new opioid bill and weighs the role of public health solutions, state and local governments will finalize their overdose data and release the final death toll for 2017. Even once the data arrives, it still may not tell us where the crisis is heading. It’s possible that the slowdown in overdose deaths in late 2017 means that state and local public health-based strategies are starting to work. Or we could be too late: one of the grimmer theories is that the opioid epidemic has devastated D.C.’s cohort of longtime heroin users to the point that there are fewer people left to die. Whether the overdose rate is slowing or simply catching its breath, the urgency of the situation demands improved strategies and immediate resources to save lives now. It will take a sustained effort to improve treatment and rehabilitation to finally stem the tide of the epidemic; but in the meantime, we must continue to use critical tools like naloxone to ensure there are still lives left to be saved.

Matthew R. Pembleton is the author of Containing Addiction: The Federal Bureau of Narcotics and the Origins of America’s Global Drug War (UMass Press, 2017) and teaches at American University. He is also a history consultant at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Follow him on Twitter at @mattpembleton.

Kathryn Zickuhr is the Deputy Director of Policy for the D.C. Policy Center. Follow her on Twitter at @kzickuhr.

Notes

[1] See “Table 2. Comparison of Opioid-Related Intoxication Deaths by Place of Occurrence, Maryland, January — September, 2017 and 2016” (page 11). Quarterly Overdose Death Reports, 2017 Quarterly Report – 3rd quarter.

[2] Despite its growing profile in public discussion of the opioid crisis, naloxone is not a new drug. The very first opioid antagonist action was observed in 1915 and the first antagonist drug—nalorphine—was developed in the 1940s in the quest to find non-addicting alternatives to morphine. Naloxone came along in the 1960s and was preferable because it worked in a more targeted way than its predecessors. It’s “a common myth,” says Butsch, “that Narcan is a brand new wonder drug. I’ve been a paramedic since 1989 and we had it back then.”

[3] Naloxone doesn’t actually flush the opioid molecules from the brain—it only prevents the molecules from landing on a receptor. It also has a relatively short half-life, so it sometimes requires larger, sustained doses to keep the opioid molecules at bay.

[4] It has not escaped the notice of critics that the pharmaceutical industry, having played a central role in creating both the problem and some of the most important tools and solutions, is now profiting on both sides of the crisis. An essay in the New England Journal of Medicine argued that policymakers should “explicitly call on manufacturers to reduce the price of naloxone and increase transparency regarding their costs,” in addition to other cost-reducing measures.

[5] So far, school officials report only two cases of having administered naloxone, both in Anne Arundel county.

[6] This number does not necessarily represent the number of lives saved, as each dose does not necessarily represent a live saved; as mentioned previously, it’s long been standard protocol for paramedics to administer the drug to any patient who is unresponsive and in respiratory distress. In addition, some overdoses require multiple administrations, and not all fatal opioid overdoses or successful naloxone “saves” are recorded.

[7] It’s important to remember that not everyone experiencing opioid addiction is ready to talk about treatment. When people come in for needle exchanges at Bread for the City, Chief Medical Officer Dr. Randi Abramson says, staff members don’t push treatment immediately; instead, their goal is to slowly develop a relationship and build trust. Once people are comfortable, “they can start to talk about treatment,” but only if they’re ready for that conversation. D.C. DOH’s Kharfen agrees: “The physical clean needle means that a virus doesn’t get transmitted, but the success of the program is the connection between those who provide syringe services and the people they serve. That is the ingredient that makes this all work so well. … There’s trust, credibility, and integrity, and respect for individual where they’re at.”

[8] Despite the inflammatory findings, Doleac and Mukherjee say their paper should not be taken as a directive to decrease naloxone access, but a caution that naloxone alone—without treatment options—would not solve the opioid crisis.

[9] These are Community of Hope, Bread for the City, United Health Care, Whitman-Walker Health, and Mary’s Center

[10] The Urban Institute reports that lack of insurance coverage is a common barrier for low-income adults seeking treatment for opioid use disorder; importantly, both D.C. and Maryland expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, improving access to treatment for low-income adults. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that 45 percent of total buprenorphine spending in D.C. (and 39 percent in Maryland) was financed by Medicaid in 2016.

[11] Initial data on Medicaid reimbursement analyzed and published by the Urban Institute backs this up: fewer than 100 units of naloxone were reimbursed by Medicaid in 2016, suggesting that community health centers are the major way naloxone is distributed in D.C.

Update 5/4/2018: This report has been updated with new data about successful overdose reversals from D.C. Health’s Naloxone Distribution Program. Over 3,000 Narcan kits have been distributed through the program in 2017 and 2018 to date.