On May 26, 2021, D.C. Policy Center Education Policy Initiative Director Chelsea Coffin testified at the Special Committee on COVID-19 Pandemic Recovery & Committee of the Whole Joint Public Oversight Hearing, addressing learning gaps and ensuring that students’ mental and physical health needs are met. You can read her testimony below or download a PDF version here.

Good morning, Members of the Special Committee on COVID-19 Pandemic Recovery. My name is Chelsea Coffin and I am the Director of the Education Policy Initiative at the D.C. Policy Center, where our education research focuses on how schools connect to broader dynamics in the District of Columbia. I will focus my testimony on your questions of addressing learning gaps and ensuring that students’ mental and physical health needs are met, and five reasons why we should keep an eye on what this means for high school students in particular during recovery.

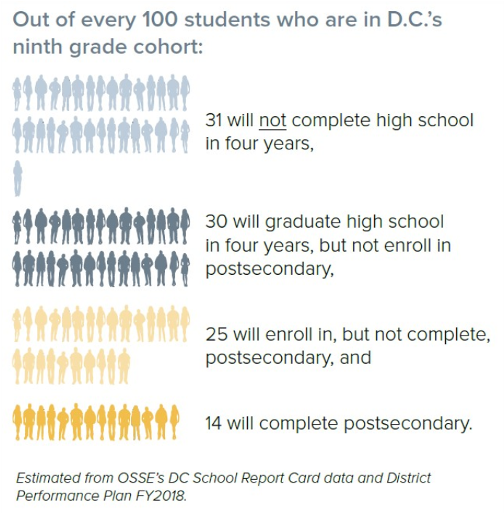

First, even before the pandemic, available data indicate that high school and the transition to college or career could be a challenging period. In 2019, learning outcomes on D.C.’s state assessment for high schoolers compared to students in grades 3 to 8 were 3.8 percentage points lower in English Language Arts and 13.6 percentage points lower in Math.[1] And most of D.C.’s high schoolers do not complete postsecondary: Out of every 100 ninth graders, an estimated 14 will complete postsecondary within six years of high school graduation. We don’t know the full picture of outcomes after high school, but high school graduates born and living in D.C. as young adults (ages 25 to 34) earn $24,000 a year[2] compared to a median family income of $126,000 for a household of four in D.C.[3]

Second, what we know about high school students during the pandemic suggests that they have faced more extreme challenges compared to younger students in some ways this past year. Although some have thrived in a virtual environment, many of the high school students who participated in our fall 2020 focus group thought the pandemic would have a negative impact on their futures, especially as they begin transitioning to college or to a job after high school (in addition to experiencing as lack of motivation, difficulty managing distractions at home, or lack of structure that may have affected younger students as well).[4] In an EmpowerK12 survey of 2,500 public charter school students, high schoolers’ responses indicated that they were the least confident in their ability to succeed during distance learning compared to students in other grade bands. Finally, available information from DCPS and public charter schools suggests that high schoolers are less likely to learn in person than elementary school students this school year.

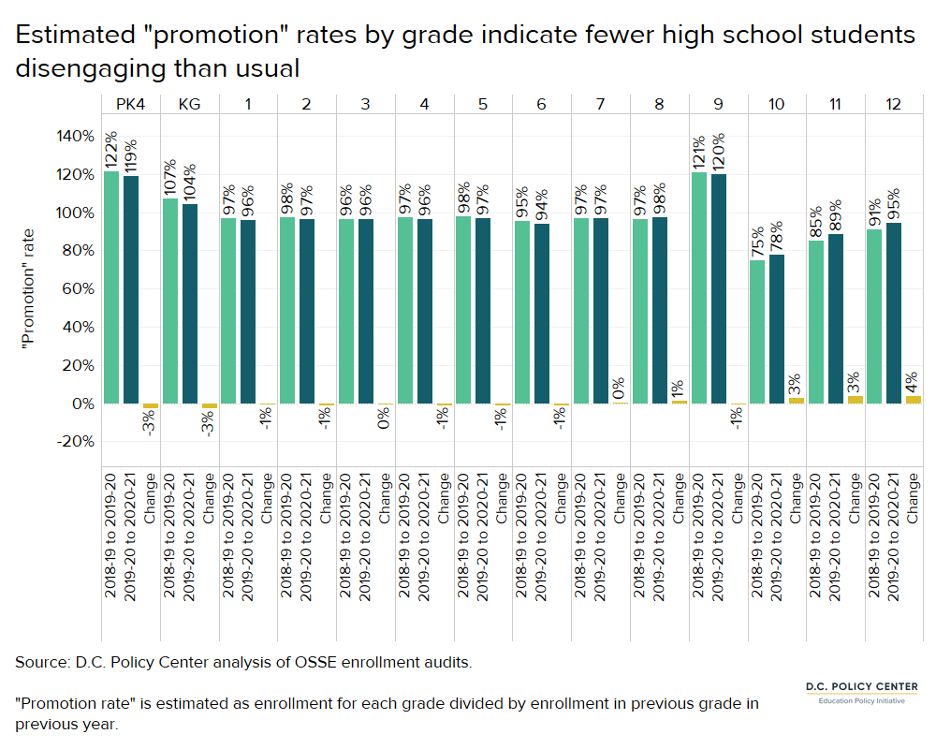

Third, an increase of 496 students in high school enrollment shows a trend that is counter to a decrease of 974 students across all grades. In school year 2020-21, many students (especially for non-compulsory pre-kindergarten, adult, and alternative programs) disengaged, transitioned to homeschooling, or left for other states, private schools, or childcare centers. Upper grades tell a different story: Grades 8, 10, 11, and 12 were the only grades where relatively more students moved into the next grade compared to the previous year. For example, on net, 95 percent of 11th graders moved into grade 12 in 2020-21 compared to 91 percent in the previous year (a four-percentage point increase). By comparison, kindergarten experienced a three-percentage point decrease in students who moved into this grade. More high school students persisting could be a good sign, but it could also mean that high school students were able to stay enrolled due to relaxed promotion requirements and less rigorous attendance policies, both of which could change next year and mean many high school students disengaging at once.

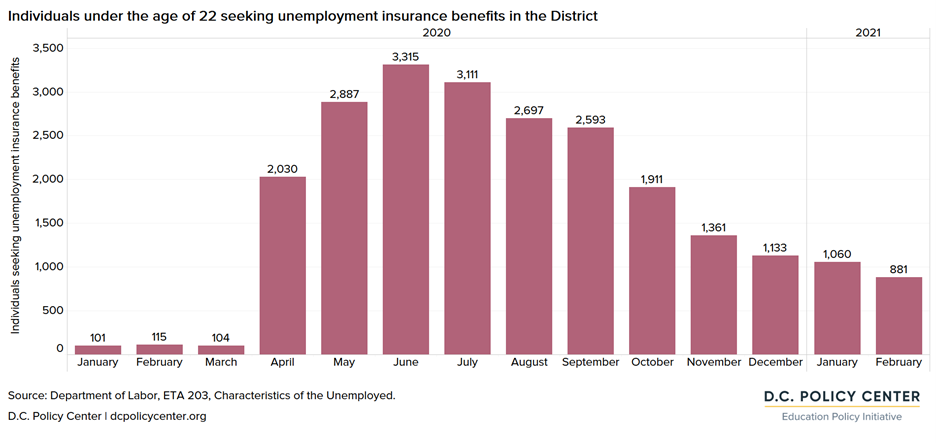

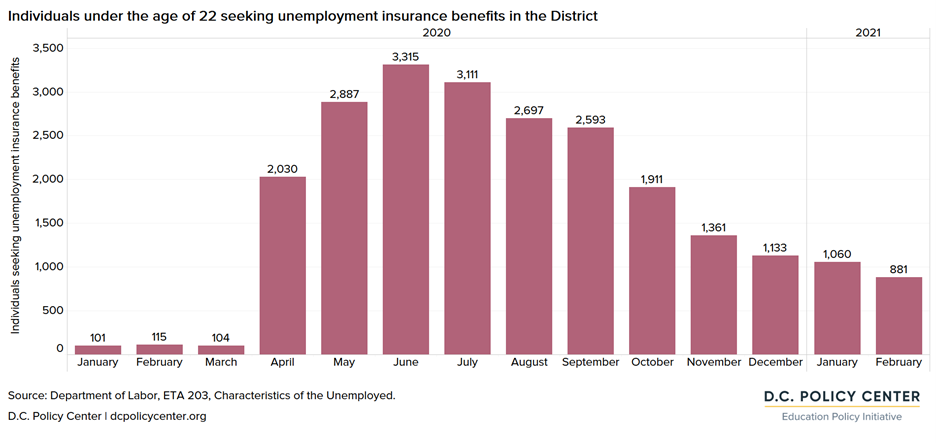

Fourth, the transition to college or career also seems to be more challenging during the pandemic. It is too soon to know postsecondary enrollment for the class of 2019-20 that graduated during the pandemic (in 2018-19, 56 percent of graduating seniors continued to postsecondary within six months of graduation),[5] but as of February 2021, the percentage of seniors completing FAFSA forms was down by three percentage points compared to previous year, indicating that fewer are seriously considering college (around 175 fewer applications).[6] In addition, it is now more difficult for youth to find a job: Eight times as many D.C. residents under 22 years old are unemployed compared to a year ago as of February 2021.[7]

Fifth, high school students, especially at higher grades, have much less time to go through the necessary steps of recovery. The city can increase focus on high schoolers starting with school-based academic recovery programs and access to mental health care resources over the summer and fall, the Marion S. Barry Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP) expansion from serving 10,000 to 13,000 14-to-24-year-olds with an earn and learn program, as well as additional funding in the budget to overage high school students designated at-risk and high school students who are English Learners. It will be also crucial to assess high school students’ academic and socio-emotional needs in the fall of 2021 and monitor the long-lasting impact of the pandemic on the District’s high school students.

I thank you for the opportunity to testify. I am happy to answer any questions you may have.