On February 12, 2018, the Trump Administration announced it had eliminated funding for the DC Tuition Assistance Grant (DC TAG) program in its Fiscal Year 2019 Budget Request to Congress. If the Congress follows through—and this is still a big if —District families will lose $40 million in federal funding that helps them pay for college.

DC TAG was established in 1999 to provide grants of up to $10,000 per academic year toward the difference between in-state and out-of-state tuition at public colleges and universities across the United States. Alternatively, students can receive up to $2,500 towards tuition in private universities in the Washington D.C. Metro Area or private Historically Black Colleges and Universities nationwide, as well as public 2-year community colleges. The program is open to youth who are seeking a college degree for the first time. It is broad-based with a high income eligibility limit ($750,000 of taxable family income).

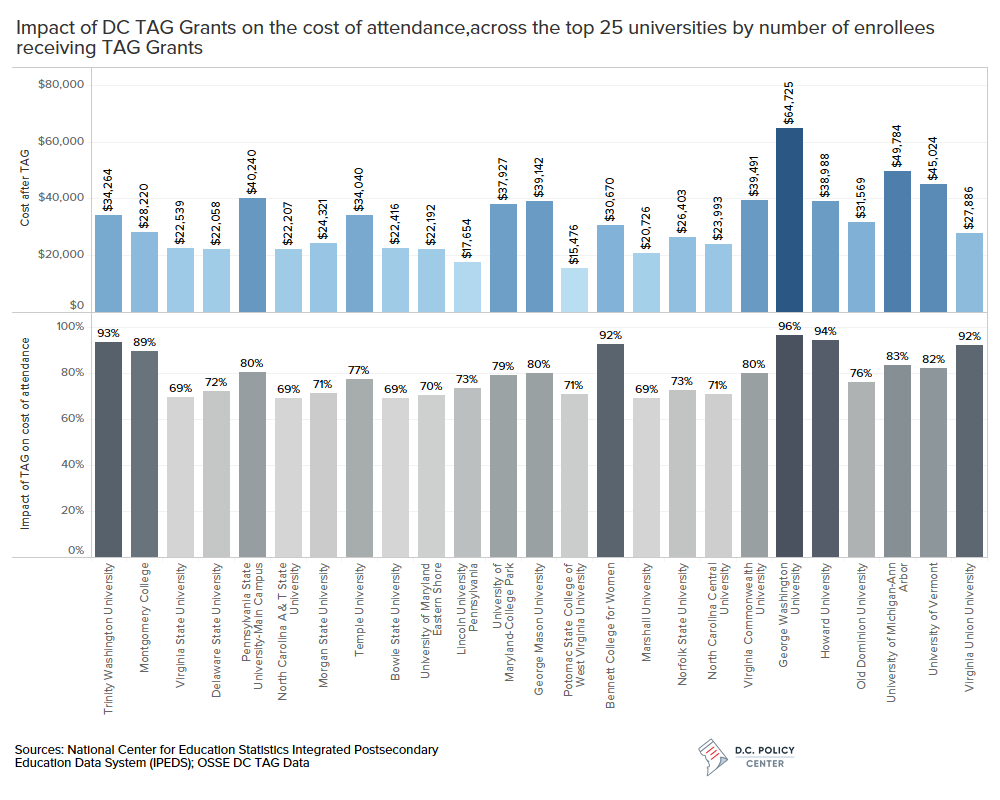

The DC TAG award levels have not changed since the program’s inception while the college costs have increased 2.5 times since 1999. Still the program is a crucial element in the mosaic of funding sources families must put together to pay for college. For example, at UMD-College Park and George Mason University—two of the most popular schools among DC TAG recipients—the $10,000 DC TAG grant would wipe away half the difference between in- and out-of-state tuition. At Virginia State, Temple, and Bowie State, the grant would cover the entire cost differential.

The DC TAG program was originally set to expire after 10 years but was reauthorized in 2008 through 2012. The Congress did not renew the authorization since then, but every year the program has been funded both in the executives’ budget proposals and the Congressional appropriation bills.

What is at stake?

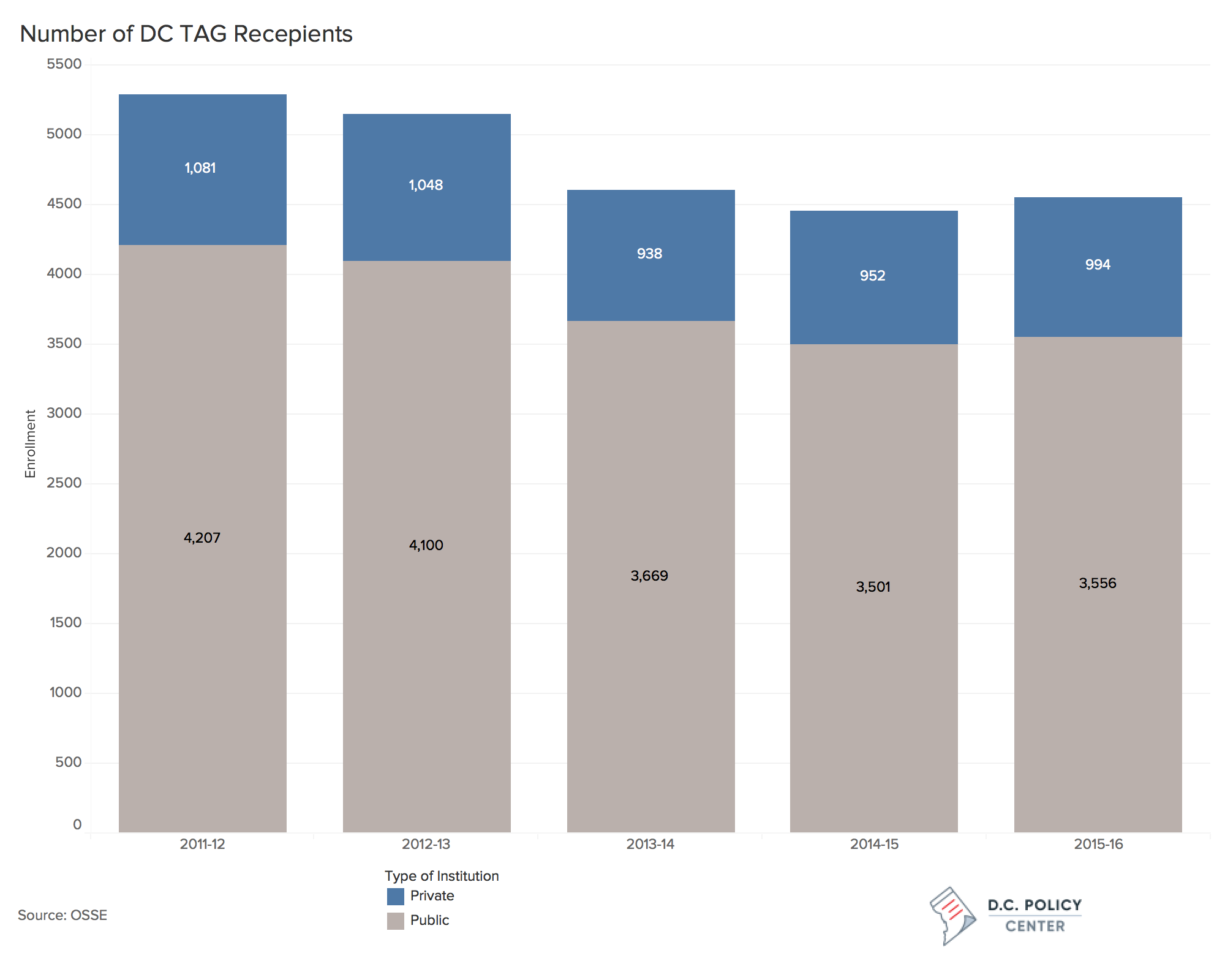

Since its inception, the DC TAG program supported 26,000 students. We have detailed data for school years 2011-12 to 2015-16, which show that during this period, 11,759 students received $158 million in awards.

Participation in DC TAG peaked in 2011-12, and since then has declined by about 800 and settled around 4,500 per year. To compare, about 2,500 of the about 3,200 students who graduate from D.C. high schools attend college within one year, and about 2000 of these students attend out-of-school colleges. We do not have data for recent years, but data from school years 2006-07 to 2013-14 show that on average about 1,300 students who have just graduated high school have applied for and received DC TAG grants. This puts the coverage rate among first-year college students at 65 percent. About half these students successfully complete college within six years. This is below the national average of about 60 percent.

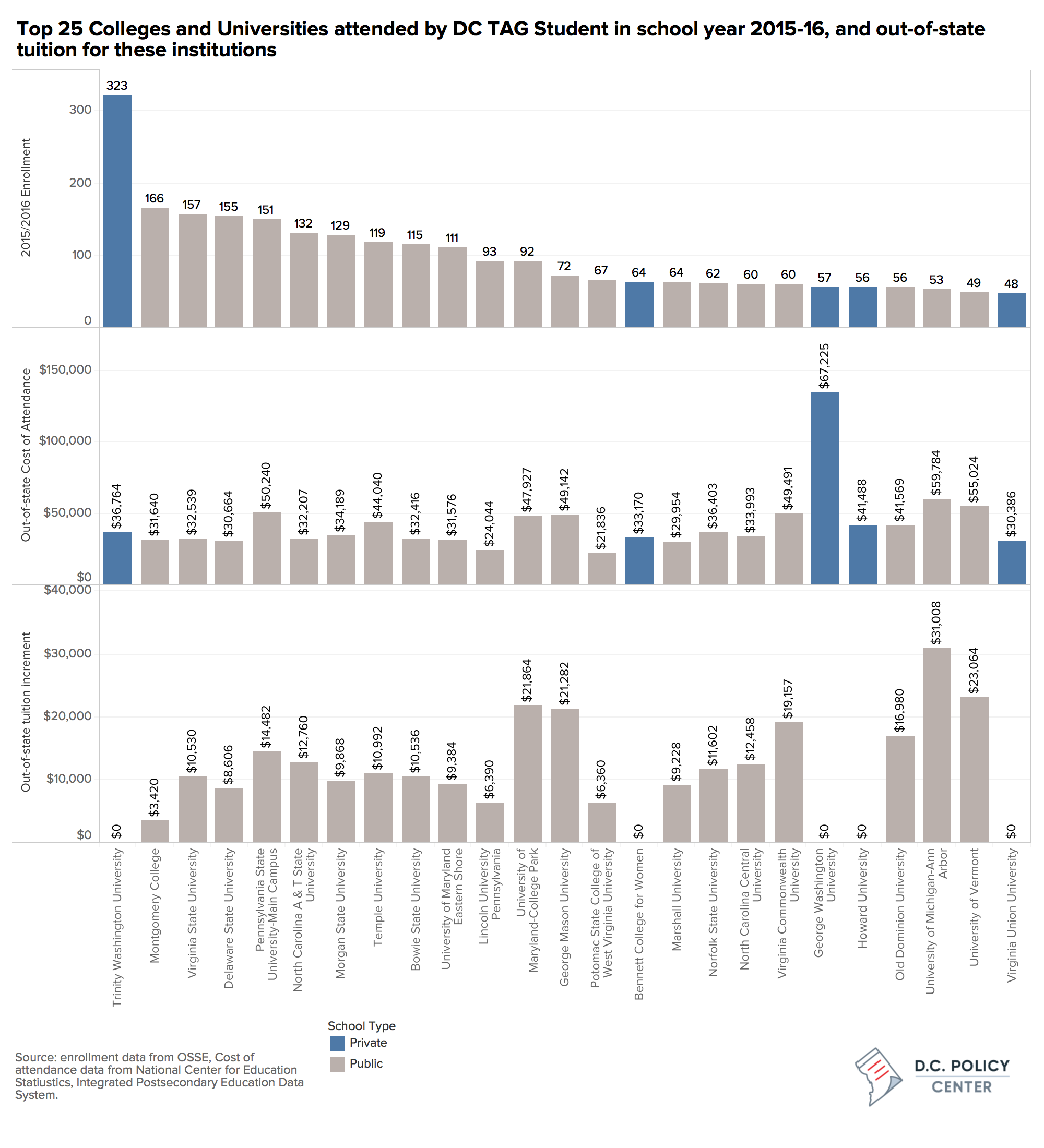

During the five-year period for which we have data, DC TAG recipients attended 421 universities across the country. A fifth of the students chose HBCUs or private schools in the metro region and were eligible for the lower benefit ($2,500). The rest attended public schools and received up to $10,000 depending on the differential between the in-state and out-of-state tuition. Students most often chose institutions in Maryland (a fifth of the recipients over the five-year period) and Virginia (12.5 percent), followed by North Carolina, the District, and Pennsylvania. The most popular school among the DC TAG recipients is in the District: In the 2015-2016 school year, seven percent of DC TAG recipients—and a third who chose private schools—attended the Trinity Washington College.

For many, the DC TAG provides a meaningful reduction in cost of attending college. For example, at Trinity, where the annual cost of attendance (including tuition, fees, and board) is $36,700 for an average student, the TAG grant would reduce cost of attendance by 7 percent. Given that most DC Tag recipients can live at home while attending Trinity, the impact of DC TAG is probably much higher. We estimate it to be a reduction of about 15 percent in the cost of attending college.

At the Virginia State University, the third most popular school among DC TAG recipients, the grant hits its sweet spot as the cost differential between in-state and out-of-state tuition ($10,500) is very close to the maximum grant amount. At this school, as well as Marshall University in West Virginia, Bowie State in Maryland, and North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, the TAG Grant can reduce cost of attendance by a third.

Who takes part in the program?

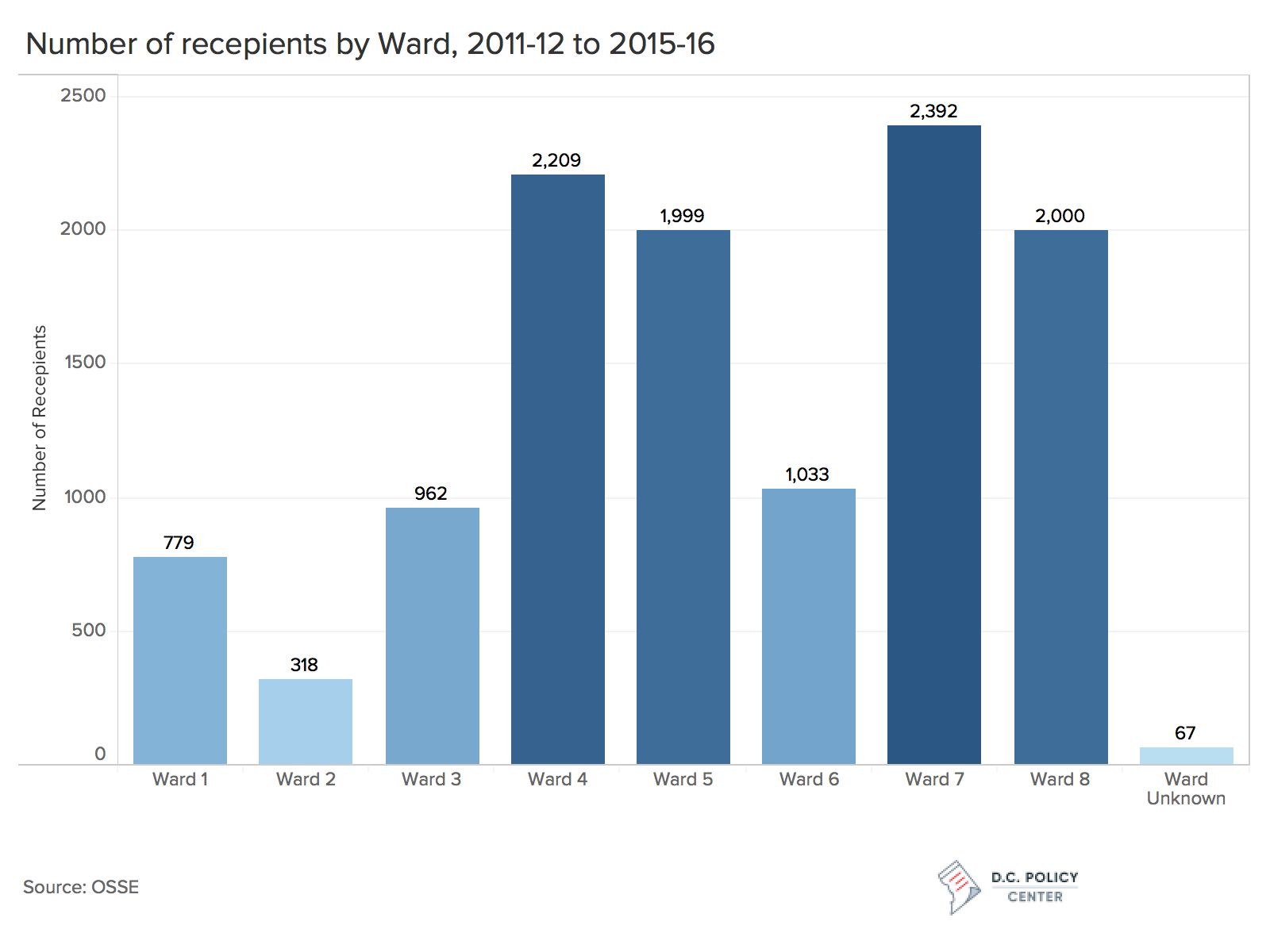

Of the 11,700 distinct students who received DC TAG grants between 2011-12 and 2015-16 school years, most lived in Wards 7 and 4, followed by Wards 8 and 5. These students received collectively 70 percent of all amounts awarded. The average award was highest among students from Wards 2 and 3 ($8,419 and $7,250, respectively), and students who reside in Ward 8 received the lowest average award at $6,123.

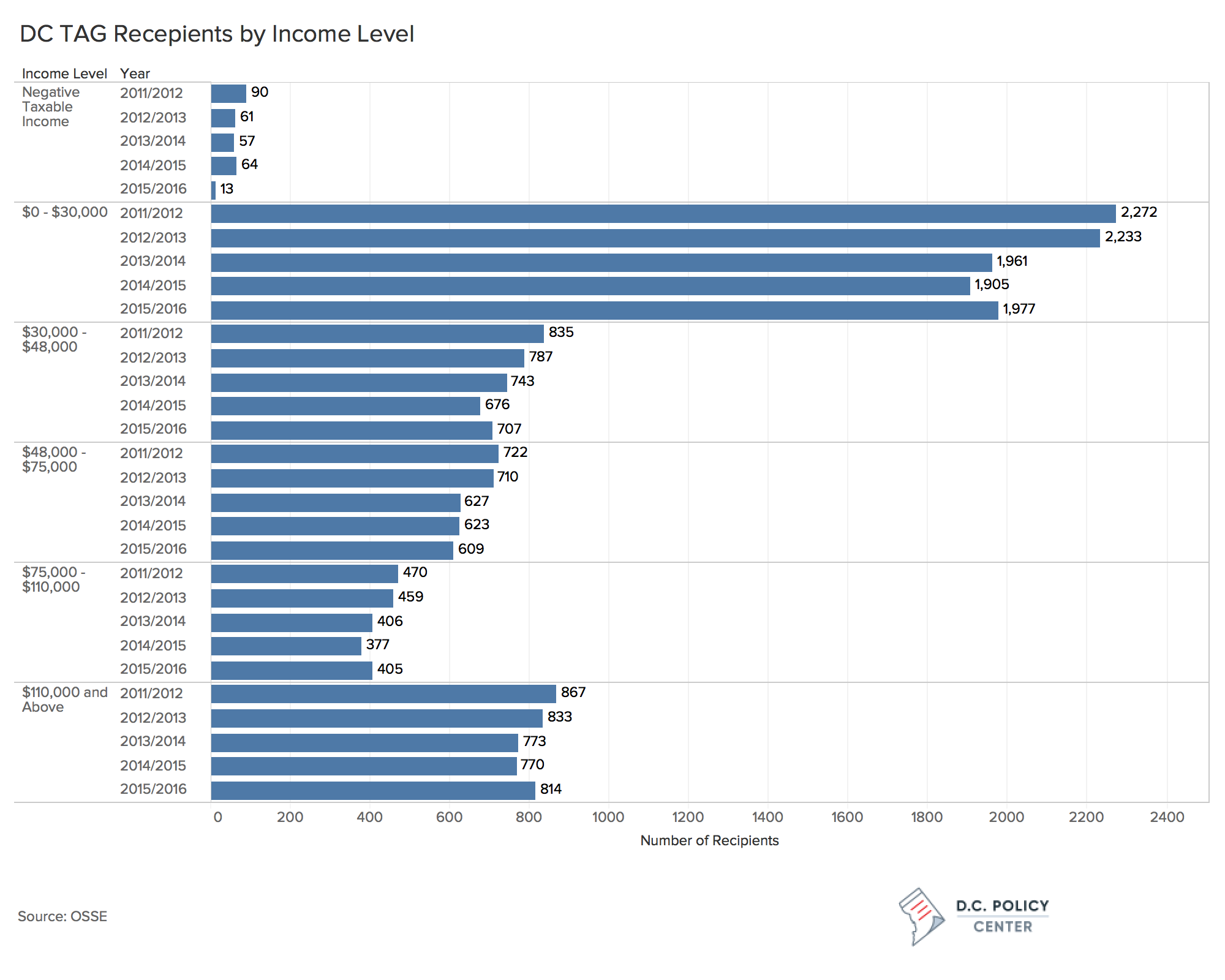

The program is most popular among low-income residents. Across the five school years for which we have data, the share of students from families with incomes under $30,000 has remained at around 44 percent. (Fewer students received grants in this income group in 2015-16 school year compared to 2011-12, but shares have remained stable since the number of recipients have declined across all income levels.) About 18 percent of all awards have gone to families with taxable incomes above $110,000, up from 16.5 percent in the 2011-12 school year.

What next?

While the DC TAG program covers only a part of college related costs, it plays a large role in how families, especially low-income families, pay for college. Its elimination will surely disrupt the university attendance among students from the city’s lowest-income families. If the program were lost, the city will face the difficult decision of whether it should provide alternative funding.

If the program were lost, at a minimum, there will be pressure to replace the DC TAG funding with local funding of about $40 million. If the city considers alternative models, the funding could be lower or higher.[1] This will be added to the long list of other pressures on the city in its Fiscal Year 2019 budget including the Metro (which lost $30 million of federal PRIA funding in the President’s budget), infrastructure, education, human services, housing, and community development—all areas standing to lose federal support under President Trump’s budget proposal.

The good news is that the president’s budget is largely a wish list. The budget is now in the hands of the Congress and the final budget will look different from what the President has proposed. The budget work will begin at the House and Senate Appropriations Committees. There are currently have 12 subcommittees, which are responsible for drafting the 12 regular appropriations bills that determine amounts of discretionary spending for various federal programs. The direct federal funding for the District of Columbia falls under the Financial Services and General Government subcommittees in both chambers. Much of what happens in these subcommittees, the full Appropriations Committee, and the final budget (or continuing resolution) negotiations will depend on how much influence the city can exert, especially through Eleanor Holmes Norton, who remains confident that much of the federal spending for the District will remain intact.

Why now?

The Trump administration has significantly curtailed state and local government grants in its FY 2019 budget proposal. The budget document characterizes this as recognition for “a greater role for state and local governments and the private sector as part of the Budget’s proposals to restore Federal fiscal responsibility.” Elsewhere in the budget, cuts to housing, food stamps, and welfare will further pressure states committed to social assistance. These actions reflect the inclination of the Trump administration to shift more costs on state and local governments in areas of health, education, social assistance, infrastructure investment, and community support.

The budget proposal shows an increase in overall amount of grants to state and local governments, but this is due to a $120 billion addition for incentives under the administration’s new infrastructure plan. This plan, if enacted, would also require significant additional contributions from states and localities. Otherwise, the proposed budget cuts all state and local grant spending (other than for Medicaid and infrastructure activity) by 11 percent. The budget authority for the discretionary portion of the grants in the President’s budget proposal is lower than what is estimated to be in FY 2018 budget by $44 billion, or by 29 percent.

In education, for example, the President’s proposed budget eliminates 17 different federal programs that total $4.4 billion at the primary and secondary levels, including Supporting Effective Instruction State Grants (known as SEED), and 21st Century Community Learning Centers, which are formula grants for out-of-school time programs in high-poverty, low-performing schools. Many other programs are cut back, including the Federal Impact Aid for children who are on federal land or Indian reservations and the School Improvement Grants which go to local school boards or LEAs for improvements. The District has two specific items among the federal grants to states and localities: one is the Federal Payment for School Improvement Grants, known as the “three-sector funds” and the proposed budget keeps this amount intact at $45 million. The second, the DC TAG program, is eliminated. The budget document defends this policy decision by noting that the program is no longer necessary because unlike in 1999, the District now has resources to support the families of the District of Columbia. It also notes that the federal government does not have a clear role in supporting the cost of higher education specifically for D.C.

While this is the first time a president proposed to eliminate DC TAG, other programs in the President’s budget that had been put on the chopping block (21st Century Community Learning Centers, for one) were later restored by the Congress. So there is a great chance that the Congress will do the same with the DC TAG program. But, there is cause to be concerned. If the notion that states should take more responsibility in managing state level functions takes stronger hold, then the District (and many other urban states and localities) could go through a significant budget shock. The District’s Fiscal Year 2018 budget relies on $3.4 billion in federal grants and payments. Not all these are cut back in the President’s proposed budget (and the signs are mixed with the increased spending in the two-year budget deal), but a quick decline in federal funds and payments would require a significant rethinking of what the city prioritizes, and how it would pay for these priorities.