On November 13, 2019, D.C. Policy Center Executive Director Yesim Sayin testified on B23-0440, the “Removing Barriers to Occupational Licensing for Returning Citizens Amendment Act of 2019.” You can read her testimony below, and download it as a PDF here.

Good morning, Chairman Allen and members of the Committee on the Judiciary & Public Safety. My name is Yesim Sayin Taylor and I am the Executive Director of the D.C. Policy Center, an independent, non-partisan think tank committed to advancing policies for a strong and vibrant economy in the District of Columbia. I thank you for the opportunity to testify on Bill 23-440, which addresses how occupational licensing boards consider criminal accusations or convictions in the licensing process.

The burdens of getting an occupational license—exams, fees, training and experience requirements—may constitute too high a hurdle for those seeking jobs that do not require a professional degree. For returning citizens who cannot be considered for a license because of criminal justice system involvement that is not connected to the occupational requirements, occupational licensing is a definitive roadblock.

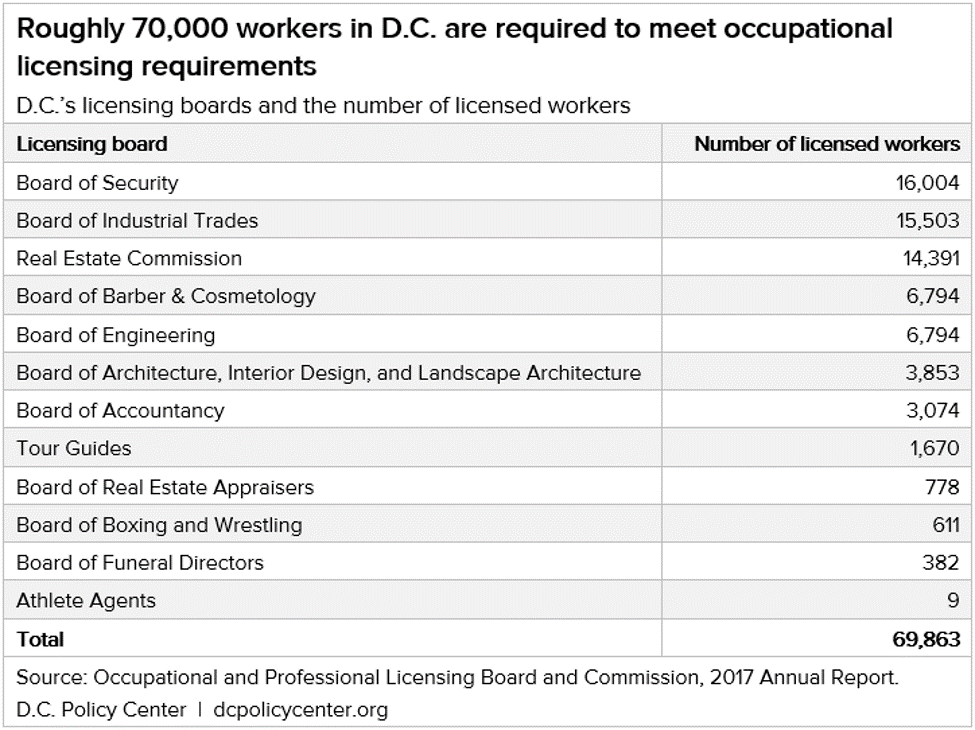

According to the city’s own reporting, its licensing boards have licensed 12 percent of all private sector employment—a exceptionally large number in a city of law firms, consultants, and non-profits. Altogether, nearly 69,863 workers in the District are in occupations regulated by a professional licensing board. The Department of Regulatory Affairs (DCRA) regulates 125 occupational and professional categories organized under 18 different boards under its Occupational and Professional Licensing Administration (Table 1). This is in addition to 20 other boards that are responsible for the licensing over 50 health and mental health occupations.

Table 1 – D.C.’s licensing boards and the number of licensed workers

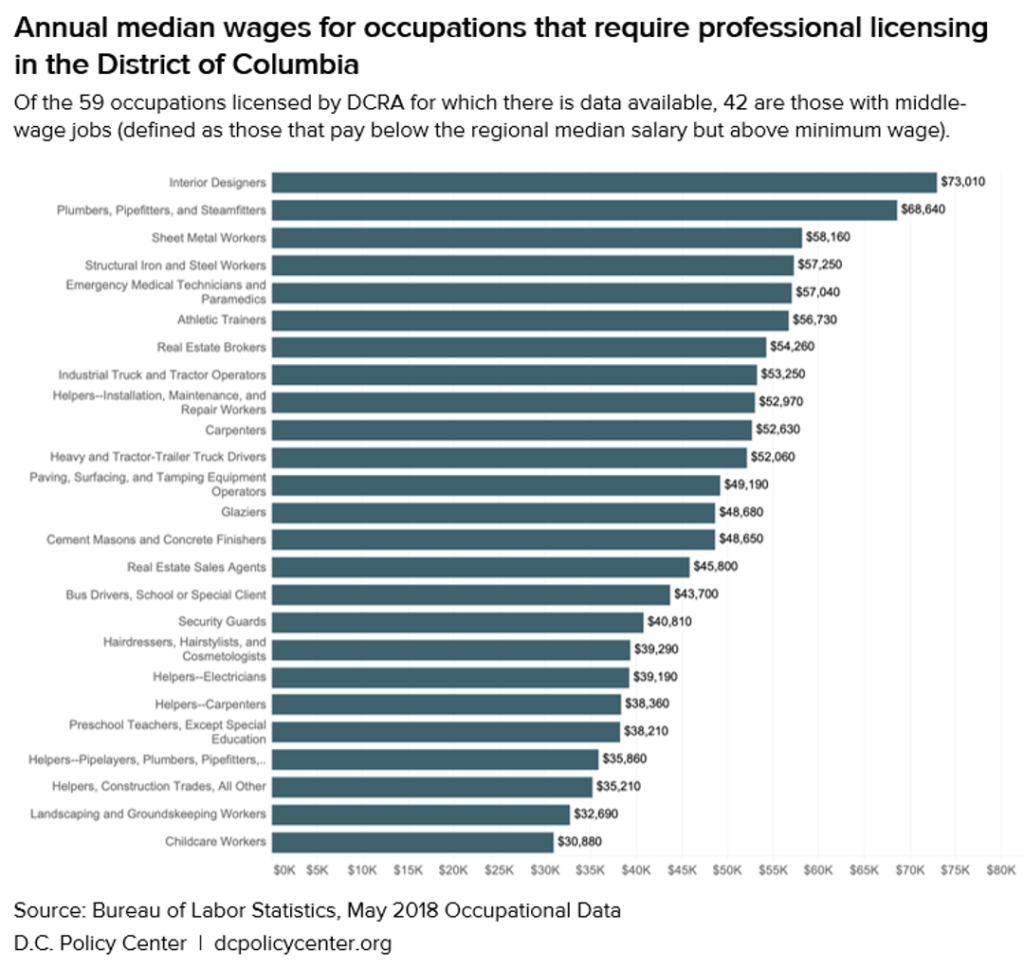

Most of the licensing under DCRA impact middle- or low-wage jobs that are attractive to low-skilled District residents who do not have high levels of education or formal training. The D.C. Policy Center has identified 59 different occupations in D.C. that do not require significant post-secondary credentialing—such as those required for doctors, counselors, social workers, or teachers—but require licensing by DCRA (Figure 1). Among these occupations, 42 pay below the median salary in the region and above minimum wage.

Figure 1 – Annual median wages for occupations that require professional licensing in the District of Columbia

This is especially relevant because relatively few returning citizens have college degrees, let alone the advanced degrees necessary to compete for the high-paying professional jobs that proliferate in D.C. A 2017 report of individuals in DOC custody found that 38 percent of those in custody did not have a high school diploma, 24 percent had a G.E.D., and 33 percent had a high school diploma; fewer than one percent had any college experience, and just 5 percent had attended a technological or trade school.[1] Typical education opportunities commonly available inside prisons may often focus on G.E.D. completion, or on providing specific skill courses.[2] Meanwhile, D.C.’s employment opportunities are concentrated in high-skill, high-paying jobs, and offers few opportunities for workers without professional degrees. The relative lack of opportunities for residents without college degrees—especially those who are returning citizens—makes the impact of these occupational licensing barriers all the more worrisome.

Denying returning citizens the opportunity to enter into an occupation on the basis of an irrelevant criminal conviction or other involvement with the criminal justice systems represents yet another barrier for residents who already face many hurdles to stable employment. As such, this legislation is an important first step to reducing collateral consequences for D.C.’s returning citizens. Going forward, I also urge the Council to address the broader sweep of licensing barriers that can also prevent these residents from entering many middle-wage professions, and which further reduce constrain opportunity in District of Columbia.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify. I am happy to answer any questions you might have.

Appendix: About the data

While there is little available public data on who is licensed by DCRA, information from the 2017 Annual Report from the Occupational and Professional Licensing Administration provides data for 12 of the 18 boards under DCRA.[3] This shows that nearly 69,863 workers in the District are in occupations regulated by a professional licensing board, accounting for nearly 12 percent of private sector employment in the city.

Using data from the Occupational and Professional Licensing Administration, the Institute for Justice,[4] and the National Conference of State Legislatures,[5] the D.C. Policy Center then identified 59 different occupations in D.C. that do not require significant post-secondary credentialing—such as those required for doctors, counselors, social workers, or teachers—but require licensing by DCRA. Comparing this data to national occupation wage data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that among the 59 occupations licensed by the District, 42 are occupations with middle-wage jobs—paying below the median salary in the region and above minimum wage.