Today, the D.C. Policy Center is releasing a new report, “Needs Assessment of Out-of-School Time Programs in the District of Columbia,” which examines the extent to which out-of-school time programs—offered after school and during the summer—are meeting the needs of children and youth attending D.C. public and public charter schools.

We worked with District of Columbia Public Schools, public charter schools, community based organizations, and District government agencies to collect information on the types of afterschool and summer programs available to local families. We then compared this information on capacity to four potential measures of need for out-of-school time programming. We also collected qualitative data from D.C. youth and families around their experiences with afterschool and summer programs through focus groups and online questionnaires.

What are out-of-school time programs?

Out-of-school time (OST) programs are programs that occur before or after school, in the summer, on the weekends, or during other times when school is not in session. (This report focuses on afterschool and summer programs specifically.) OST programs serve multiple roles, ranging from providing quality supervision for younger children during traditional work hours to first steps into workforce for older youth. Quality programs may provide children and youth with academic support and enrichment (1), supportive social environments (2, 3, 4), or simply serve as a safe space for children and youth to spend their out-of-school time (5, 6). That is, availability and quality of afterschool or summer programs matter for many reasons(7), and are especially important for children and youth facing barriers to academic success (8).

Why is this a policy issue?

What children and youth do when they are not in school matters when it comes to learning and life outcomes. Out-of-school time activities can help improve academic success, support the development of non-cognitive skills, and prove access to a safe place and supportive social environment. OST activities can also benefit the broader community (both directly and indirectly) in the form of increased productivity, lower crime rates, and other positive social outcomes.

The need for OST programs began to increase as an increasing number of women joined the labor force. In the District, the rapid population growth further bolstered this demand. The District had reversed the decline of its infant and child population around 2010, and in recent years and in recent years a larger number of families have stayed in D.C. after the birth of their first child than in the recent past (9). As a result, enrollment in the District’s public and public charter schools have increased, likewise increasing the need for out-of-school time programs serving children and youth who attend these schools. At the same time, universal pre-K programs for 3- and 4-year-olds that the city’s school began offering in 2008 have further shifted the capacity needs that may have been provided by early care and education to out-of-school time programs.

Because of their potential positive individual and social impacts, many out-of-school time programs receive funding from public and private sources that allows them to offer services at below-market rates. In D.C., the District government, the federal government, and private foundations support many OST programs; we refer to these as “subsidized” OST programs, and they are the focus of this report. There are also many market-rate afterschool and summer programs in the District, which, though beyond this report’s scope, are another important source of D.C.’s OST capacity.

The important role that the District government plays in directly or indirectly funding many OST programs raises the policy question of what to subsidize, by how much, and how to distribute these subsidies. Therefore, an important part of this policy discussion is first understanding capacity, need, and service gaps for existing programs.

The current landscape of afterschool and summer programs in D.C.

The landscape of subsidized OST programs includes those operated by public schools and public charter schools; those run by District government agencies, such as the Department of Parks and Recreation; and those organized by non-school entities that receive public funding, such as community based providers (CBOs). For programs serving youth in grades 9-12, one prominent program is the Mayor Marion S. Barry Summer Youth Employment Program, which we include in our capacity estimates.

Our survey of providers shows that:

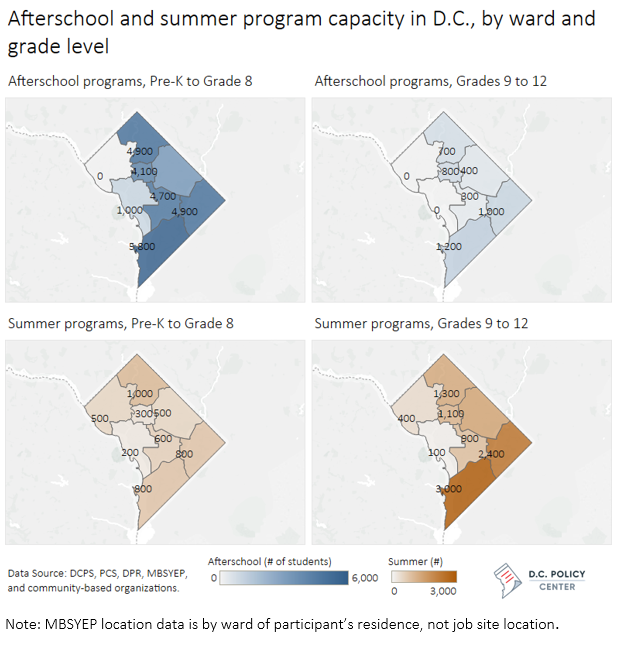

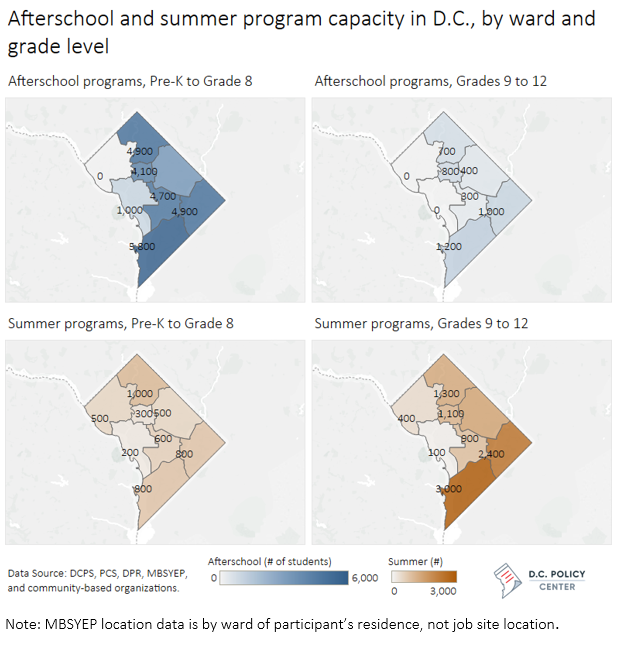

- An estimated 33,400 children and youth attend subsidized afterschool programs in the District of Columbia that are either fully or partially subsidized by public sources. This includes an estimated 28,700 D.C. children between pre-K and 8th grade, and an estimated 4,700 youth in grades 9 through 12.

- At least 15,000 children and youth participate in subsidized summer programs in D.C. Among these children and youth, an estimated 4,700 are between pre-K and 8th grade, and roughly 10,800 are in grades 9 through 12. These estimates for older youth including participants in the Mayor Marion S. Barry Summer Youth Employment Program; when we remove MBSYEP participants, the number of summer program participants in grades 9 through 12 was less than 2,800.

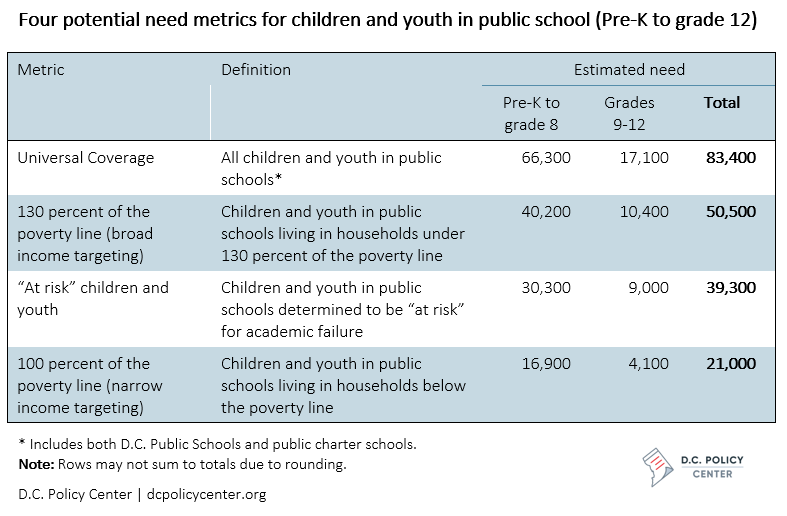

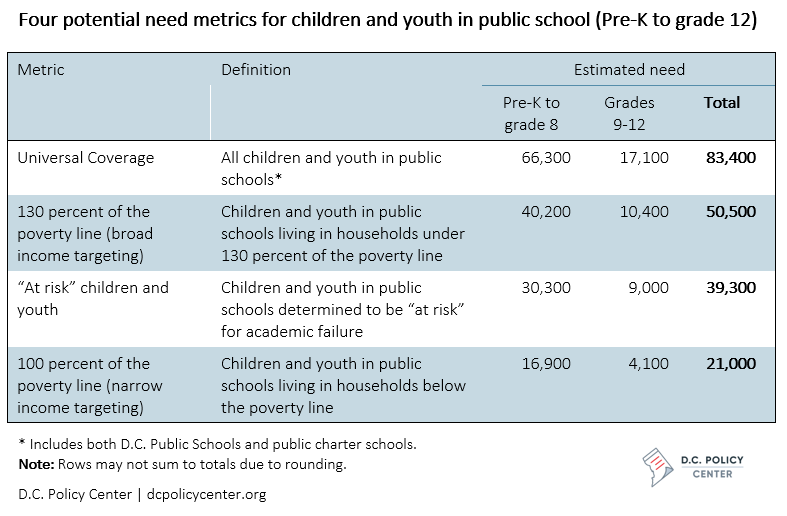

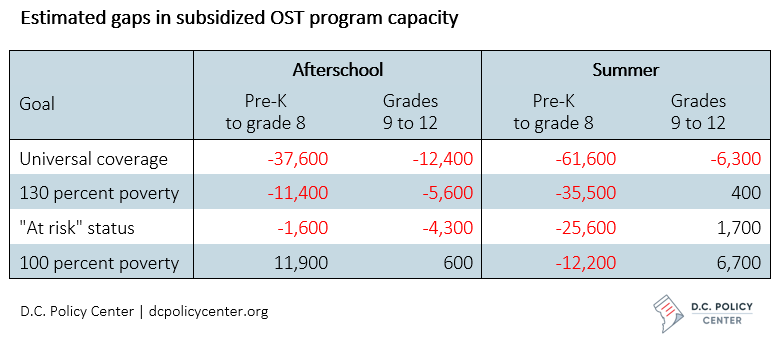

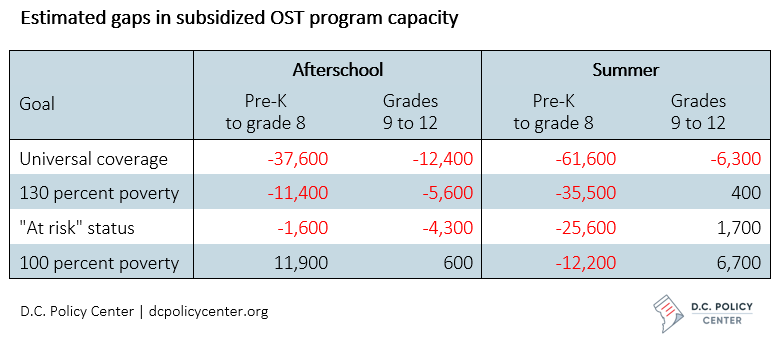

How to measure need? Four potential target populations for OST program coverage

The need for OST programs depends on the policy goal the city chooses to pursue in supporting these programs. In this report, we examine need estimates through the lens of four different policy options for financing of out-of-school time programs: universal coverage (every child in a public school receives full or partial subsidy), subsidies for children and young people in households with incomes at 130 percent of the poverty line, subsidies for those designated as “at risk” for academic failure, and subsidies for those in households with incomes at or below the poverty line.

These four metrics are meant as a starting point for characterizing the need for the District’s subsidized OST programs. They show that while universal coverage would be the most expensive option, more targeted approaches will shift priorities to different parts of the city, and would require higher effort—and additional resources—to ensure that all children and youth in the target group can participate in these programs. This could pose a significant challenge: research on programs for teens suggests that even the most successful out-of-school time programs have participation rates of about 60 percent, and even lower retention rates (about 20 percent) (10).

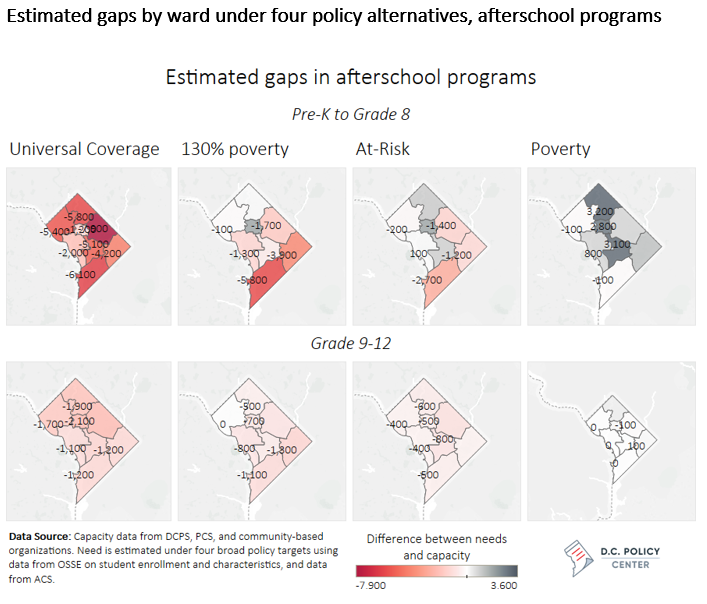

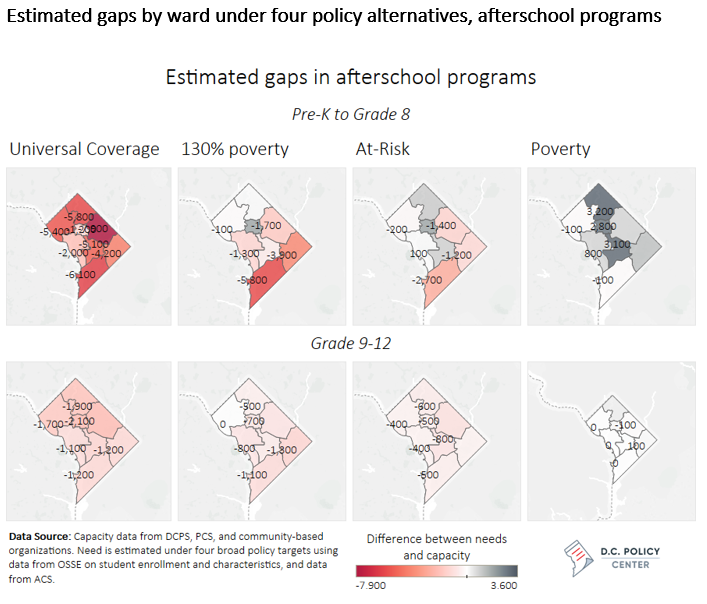

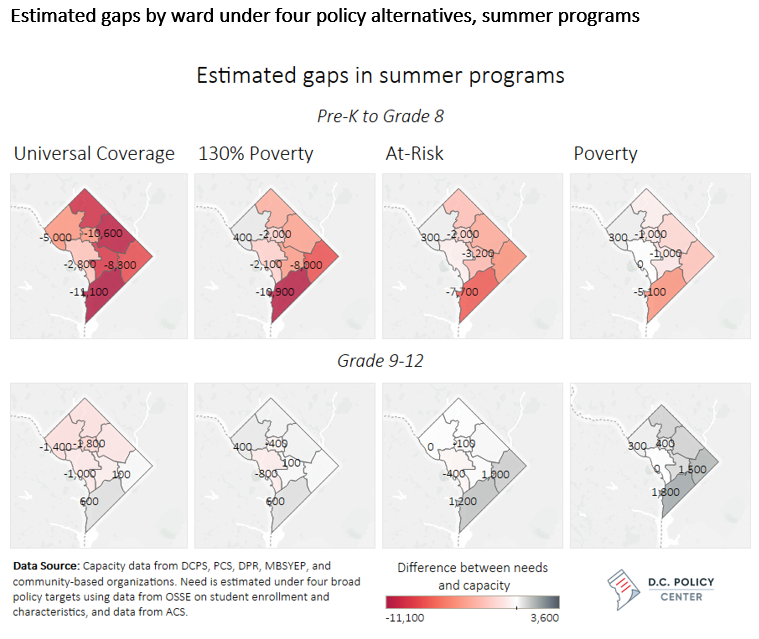

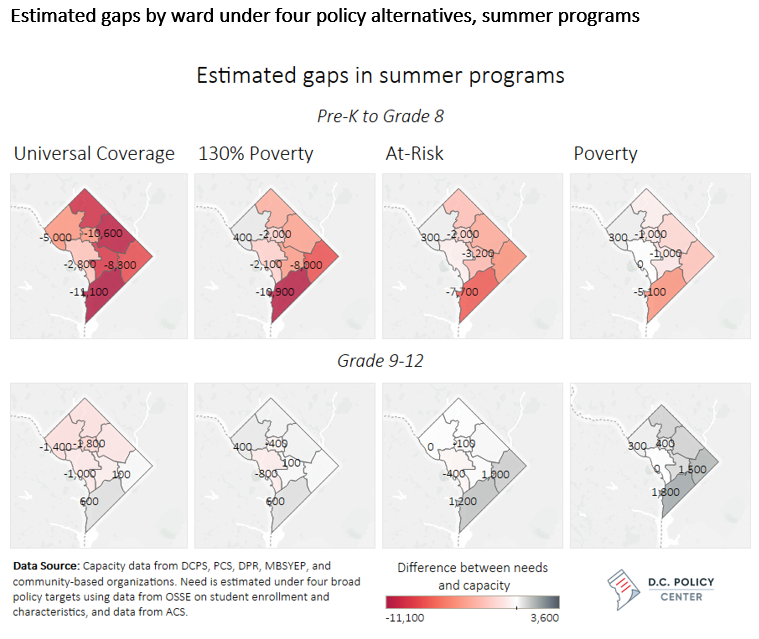

By comparing current capacity with these four levels of estimated need (below), one can broadly identify gaps in OST program capacity for different age groups and across different wards of the city.

Some of the main findings include:

- Under a goal of universal coverage for children and youth attending D.C. public schools, the District would need to subsidize 37,600 additional afterschool slots for children in pre-K through grade 8, and 12,400 additional afterschool slots for those in grades 9-12. Universal coverage for summer programming would require an additional 61,600 slots for children through grade 8 and 6,300 for those in grades 9-12.

- Several gaps remain even under more targeted policy goals, especially for the younger children. Under the narrowest target—providing subsidized OST programming capacity to children and youth in households at or below the poverty line—the District would still have a gap in summer programming of 12,200 slots for children in grade 8 and below.

- The gaps displayed under the broadest policy targets are more evenly distributed throughout the city, following the general distribution of children and families. As coverage targets narrow to focus on measures of income or other socioeconomic factors, the main coverage gaps are concentrated in Wards 7 and 8.

Youth and family experiences show significant participation barriers

OST programs in the District are very decentralized, and there is no central database of OST programs. As a result, our estimates rely on information collected from different providers; the data we used to estimate capacity, need, and gaps for subsidized OST programs is likely incomplete and imperfect.

Furthermore, our gap estimates only compare the number of seats available with the number needed under different policy options—not whether the associated programs match with individual families’ needs and preferences. Participation in these programs are not automatic, even when they are subsidized. To understand what motivates families and their children to participate in OST programs—and what prevents them—we collected qualitative data from youth and families around their experiences with afterschool and summer programs. We found that:

- Parents and caregivers have difficulty finding relevant and timely program information. OST program options vary widely by price, quality, and content, and registration deadlines may occur three or four months before the programs begin—with affordable programs filling up quickly. Parents often felt it was necessary to make a trade-off between affordability, accessibility, and quality, with quality often the factor that was lost. The challenges of finding an appropriate program were even steeper for parents and caregivers of children with special needs.

- Program hours shorter than the traditional work day were an issue for many families, creating transportation and logistical challenges. An example would be a summer program that ended at 3 p.m., well before the end of the traditional workday. Before- and aftercare, while often available, could quickly add to program costs and still may not extend hours enough to meet families’ needs. Similarly, even if a program itself was affordable, parents and caregivers said that the transportation cost required for their child to attend (in time, money, and logistical wrangling) frequently put participation out of reach. Transportation challenges were compounded when children in a family attended multiple schools, or when a family had only one caregiver.

- Our focus group with high school-age youth found that almost all had heard about OST activities in some form from their school—through morning announcements, flyers in common areas, or specific teachers or counselors (in-person and by email). Parents and caregivers were also important information sources for some participants. Young people who were already in an OST program, extracurricular class, or team sport often heard about other opportunities through that program.

- Young people expressed frustration with programs that filled their time with “busy work” disconnected from real-world outcomes and their personal or professional interests. Several young people mentioned a strong interest in STEM programs and arts-focused programs, as well as in more hands-on activities including programs that would introduce them to different types of careers.

Our Recommendations

Many of our recommendations speak to the challenges related to collecting more data and information on OST programs, including the need to measure the quality and effectiveness of programs—both in terms of outcomes and in terms of the programs’ ability to effectively engage children and youth across all grades.

On improving data collection, we recommend the following:

- Collect standardized data about OST programs provided by the District government and organizations that receive government funding.

- Work with private foundations to expand OST program data collection to programs receiving foundational support.

- Work closely with public charter schools to better understand how charter schools serve children, youth, and families through OST programs.

- Collect information on OST programs operated by fully private providers that do not receive public funding.

On further research, we recommend the following:

- Study OST provider costs, financing, and pricing models.

- Conduct further research on challenges facing groups who experience additional barriers to academic success or other unique concerns.

- Develop quality and effectiveness benchmarks.

On improving quality and effectiveness, we recommend the following:

- Work with providers to extend program hours to meet the needs of families.

- Consider supervised transportation options for program serving younger children.

- Increase the number and range of opportunities available for older youth, and more effectively engage them in OST programming.

- More fully engage schools and other nodes in children and youth’s informational networks as outreach partners.

- Improve outreach and communication with families.

About this report

United Way of the National Capital Area commissioned the D.C. Policy Center to write this report. The report received support from the District of Columbia Deputy Mayor for Education and it will fulfill the Office of Out of School Time Grants and Youth Outcomes Establishment Act of 2016 requirement to conduct a citywide OST needs assessment. We are excited to be a part of this conversation, and providing the data and analysis for the city-wide policy discussions on how to improve availability to and participation in out-of-school time programs.

There will be a discussion of the report at the launch of the DC Office of Out-of-School Time Grants and Youth Outcomes on October 24, 2017, from 9:30 am-12 pm at the University of the District of Columbia Community College (UDC-CC) Bertie Backus campus.

Click here to download the full report (PDF)

About the data

The report uses multiple data sources to develop both quantitative and qualitative evidence supporting the analysis and findings. The Methods section in Appendix I of the report describes the methods used to develop the estimates.

Economic and demographic data are from the U.S. Census and American Communities Survey (ACS) data extracts; when possible, the report cites ACS data extracts compiled by DC Action for Children’s KidsCount.org data tool.

School enrollment data are from Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) audited enrollment reports.

Capacity and enrollment data summaries are from D.C. public schools, various public reports of D.C. government agencies, and the foundation community. Additional capacity and enrollment data was collected from individual community based organizations and public charter schools, although these data sources are not comprehensive.

Qualitative data sources included two in-person focus groups conducted in July 2017 (one with high school-aged youth, and one with parents of children and youth of all ages); supplementary questionnaires distributed to parents online; and open-ended response options in the surveys distributed to out-of-school time providers and schools.