D.C.’s rent control laws, first enacted in 1985, are designed to stabilize rents for current tenants to protect them from rapid, unreasonable increases in their rents. While landlords can increase rents from year to year, these increases must be within established parameters and be predictable.

Who is covered?

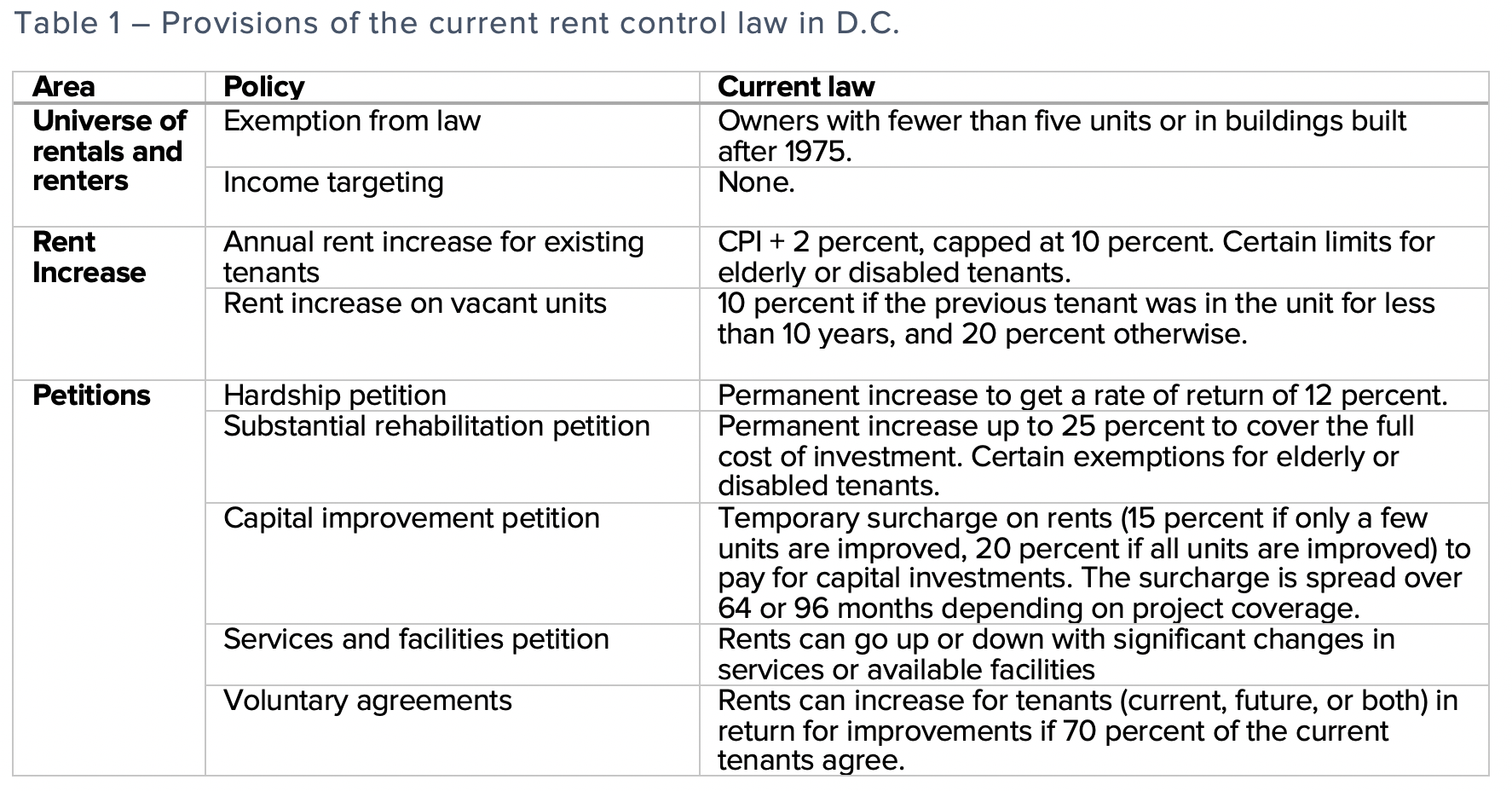

The rent control laws are written broadly, and apply to all rental properties in the city,[1] with a series of exemptions limiting their application. At present, the laws exempt: (a) housing providers who own fewer than five units, including units in condominiums and cooperatives; (b) units in buildings built after 1975,[2] (c) units that were vacant when the law took effect, and (d) buildings that are under a building improvement plan and receiving rehabilitation assistance from the city’s Housing Production Trust Fund.

What are the limitations on rent growth?

For most units, the law limits rent growth to change in the Consumer Price Index plus two percent (hereafter, CPI + 2 percent), and allows for an increase if the last increase was at least 12 months ago. Further, the landlord must give a 30-day notice of any rent increase.

When a unit becomes vacant, the rent offered to the new tenant can be increased to up to 20 percent above the rent the previous tenant paid, depending on the tenure of the previous tenant.[3] This means, as tenants turn over, rents can increase by more than the allowable CPI + 2 percent.

When can a housing provider seek larger rent increases?

A housing provider may petition city authorities[4] for larger allowable increases under five different circumstances:

Under hardship petitions, housing providers must demonstrate that their rate of return on their investment in the rental property is less than 12 percent.[5] If providers can document lower returns by sharing information about their revenues and expenditures, they can raise rents enough to earn a 12 percent rate of return on the rental property.

Under substantial rehabilitation petitions, the housing provider may permanently raise rents for a rehabilitation project, which is defined as a project that costs more than half the assessed value of the building (or the unit). After the rehabilitation petition is approved, rents could permanently increase by up to 25 percent.

Under capital improvements petitions, the housing provider can petition to temporarily raise rents by an amount enough to cover the cost of capital improvements.[6] If approved, the provider must complete the work before raising the rents. If the capital improvement is building-wide, like replacing a roof, the costs are spread over eight years and the rent surcharge is limited to 20 percent of the rent; if they pertain to some units only (like replacing windows), the costs can be spread over 64 months and the surcharge, which only applies to tenants whose units were improved, cannot be more than 15 percent of the rent. Low-income elderly and disabled tenants are exempted from the surcharge.

Under services and facilities petitions, rents can be increased if the housing provider provides a new service or facility and decreased if the provider eliminates and existing service of facility. For example, if the building closes a fitness center previously available to tenants, tenants may petition for a rent reduction.

Under 70 percent voluntary agreement petitions, tenants can voluntarily agree to increased rents in return for capital improvements, services and facilities, or repairs and maintenance. If approved, the housing provider can increase rents by the amount in the agreement only after meeting the requirements of the agreement. So long as seventy percent of the tenants agree, all tenants are included in the rent changes, including those who did not sign it.

<< Back: Main publication page | Next: How would Bill 23-873 change rent control laws in D.C.?>>

Notes

[1] The exceptions are dormitories, hospitals, rental units operated by a foreign government, and long-term temporary housing oerated by a non-profit (needs to be apporved).

[2] To be exact, the law exempts buildings with an approved building permit issued after 1975. Buildings that obtained construction permits prior to 1975 are subject to rent control even if construction was competed in later years.

[3] If the previous tenant was in the unit for more than 10 years, the cap is 20 percent, and if the tenant was in the unit less than 10 years, the cap is 10 percent. Previously, rents were allowed to increase to match the rent charged for a substantially similar unit, but no more than 30 percent. The Vacancy Increase Reform Amendment Act of 2018 changed this provision. (D.C. Law 22-223, 66 DCR 185, Effective Feb. 22, 2019)

[4] The petitions are filed with the city’s Rent Administrator. If the Rent Administrator denies the petition, the housing provider can seek a hearing at the Office of Administrative Hearings to settle the dispute.

[5] Here, rate of return is defined as net income earned over a year as a share of provider’s equity in the building.

[6] These include work to rehabilitate or improve a housing accomodation, or replace items that have exhausted their useful life. The investment must be “depreciable,” and include things like replacing a roof or an elevator, installing new windows, installing new plumbing or appliances.