The District is relying on its large rainy-day funds to buy two years’ worth of stability for its budget. One important advantage of this strategy is that, for now, these savings from previous years are the most secure source of funds at the District’s disposal. All other revenue, especially the tax revenue, is subject to great risk and uncertainty.

COVID-19 has dramatically altered the District of Columbia’s fiscal picture.

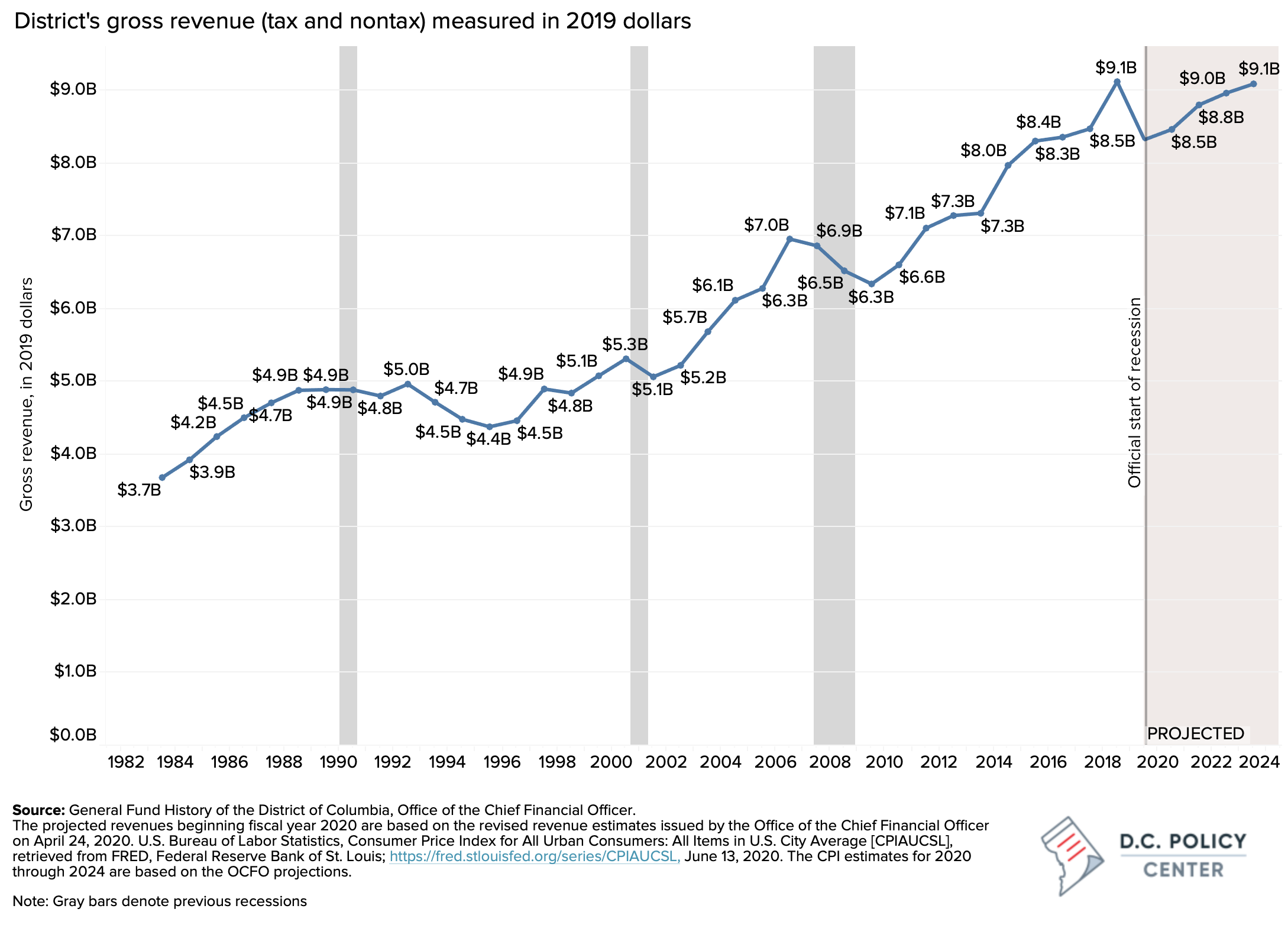

The CFO’s updated revenue estimates tell us that it will take the city at least two years to gain back the deep losses incurred in a matter of two months. When these numbers are adjusted for inflation, we see that recovery will take even longer: the purchasing power of the government is declining by 8.74 percent between fiscal years 2019 and 2020, and it will take the city four years to make up this loss.

Given the unprecedented economic and social impacts of the pandemic, one option is to raise taxes in order to increase government spending to help households and small businesses that are hurting. While the economic needs are real, increasing taxes to meet them will be more difficult under the new “fiscal normal” with weaker economic fundamentals, an unprecedented amount of uncertainty, a more fragile tax base, and fewer positive revenue surprises throughout the next four years.

The proposed budget is buying time for a projected two-year recovery.

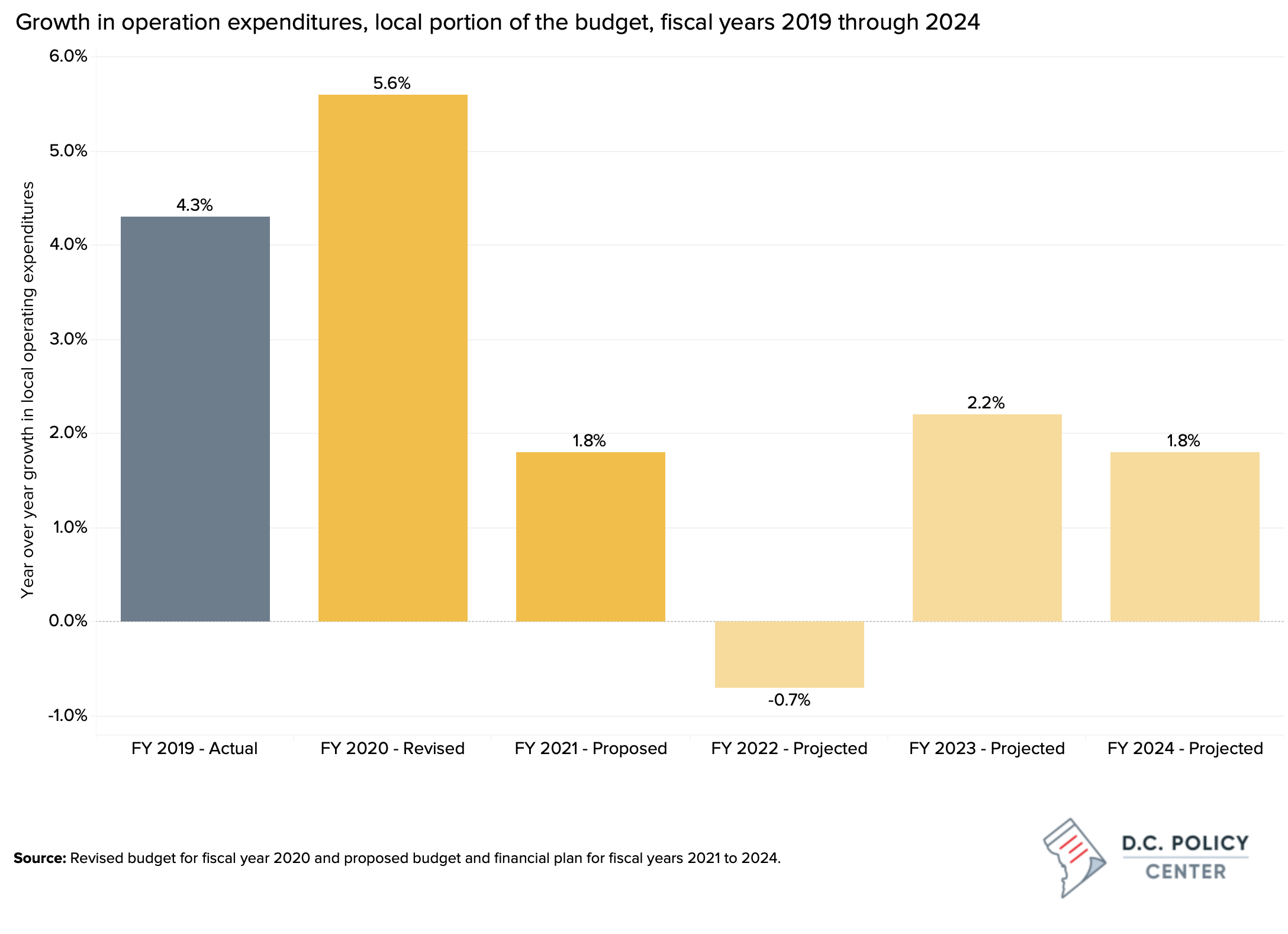

The Mayor’s revised fiscal year 2020 and proposed fiscal year 2021 budgets largely maintain spending and fill gaps with the use of the city’s rainy-day funds (and some federal money). Spending is constrained by eliminating pay increases for government workers, but budgets avoid furloughs or staffing reductions and do not necessitate structural changes or major cuts to any key government function. The proposed fiscal year 2021 budget has kept most of District’s human services programs at their prior levels with some enhancements to homelessness programs and increased funding for public education and the police department.

By drawing heavily on the fund balance to make up for lost revenue, the budget secures a holding pattern over the next two years, waiting for the economy to regain its footing. While many cities and states around the country are furloughing their workers and cutting funding for services, the District can afford to hold steady for these two years thanks to its robust rainy-day funds accumulated since the end of the Great Recession. The city plans to use $834 million from its savings in fiscal year 2020 and $613 million in fiscal year 2021, exhausting most of its usable fund balance.The current recovery projections, combined with the “hold steady” approach to the budget and heavy reliance on the rainy-day funds, inevitably create a lot of pressure on fiscal year 2022. That year, revenues are projected to grow by $450 million—signaling the beginning of economic recovery—but this is not enough to maintain spending at fiscal year 2021 levels. Barring a positive revenue surprise, the operating budget is projected to decline by 0.7 percent to make the financial plan work.

The uncertainty hits at a time when the District was betting on strong growth.

We are now officially in a recession that took swift hold when the city was projected to have strong economic growth. This growth was necessary to ensure that the District’s current-year revenues could pay for its current-year expenditures: The fiscal year 2020 budget, when initially adopted last summer, included $391 million in fund balance use—not in response to an unforeseen need or emergency—but as a placeholder for anticipated upward revisions to revenue. Indeed, by December of 2019, only three months into the fiscal year, revised revenue estimates had already added $165 million to the projected revenue, mostly due to stronger-than-expected job and income growth, signaling that by the end of the year, the revenue would grow sufficiently enough to erase the need for any use of the fund balance.

The pandemic upended these expectations.

Recovery will likely be slow, its timing largely dictated by the availability of a cure or a vaccine. And the District’s economic performance and revenue raising capacity will likely be impaired by weaker labor market fundamentals and greater risk and uncertainty.

Labor market indicators are weaker compared to 2011-2015, when the city was recovering from the Great Recession.

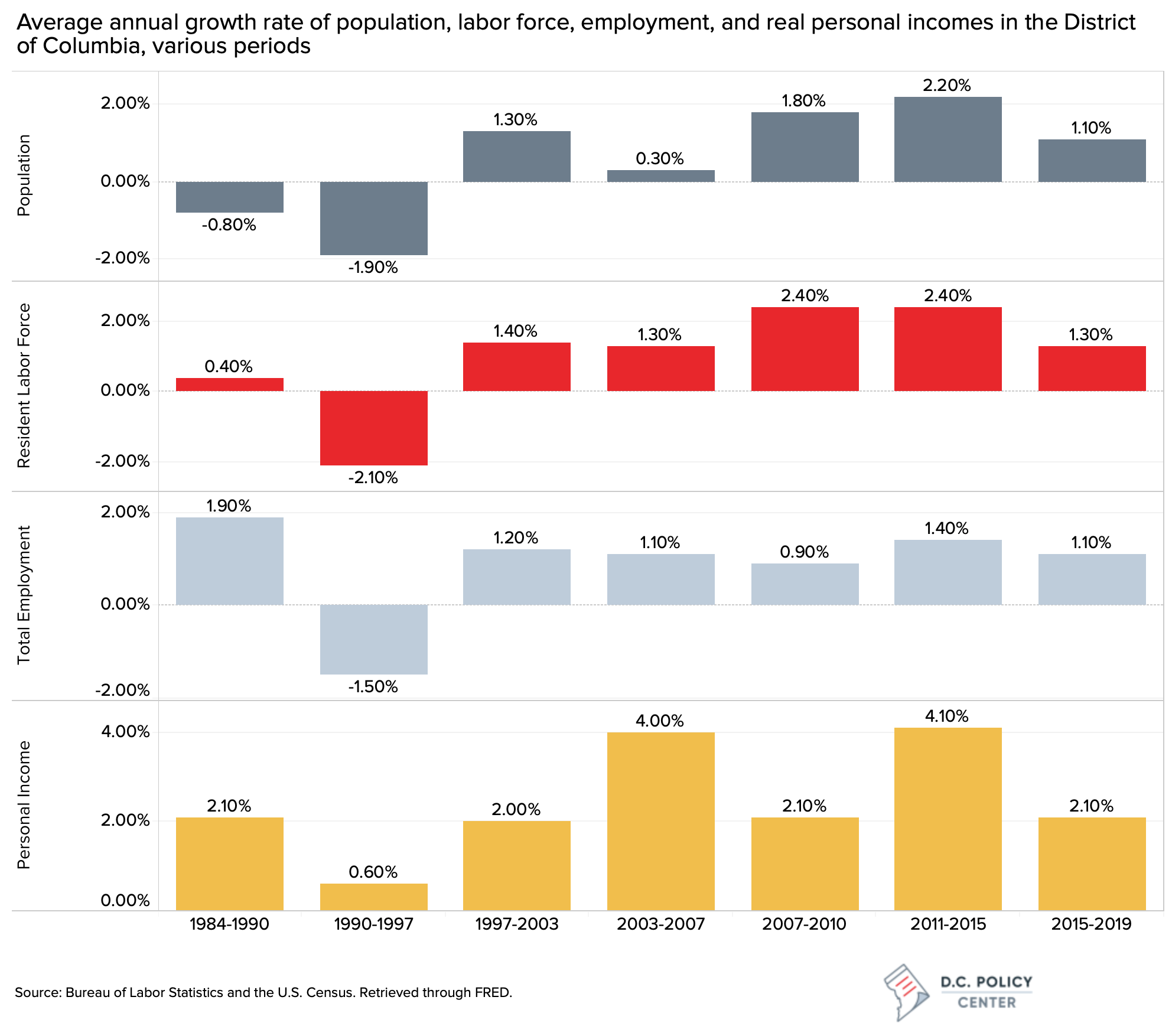

Labor market fundamentals—increasing population, labor force, jobs, and incomes—which had helped the city recover from the Great Recession with relative ease compared to the rest of the country, have not been as strong in the last few years.

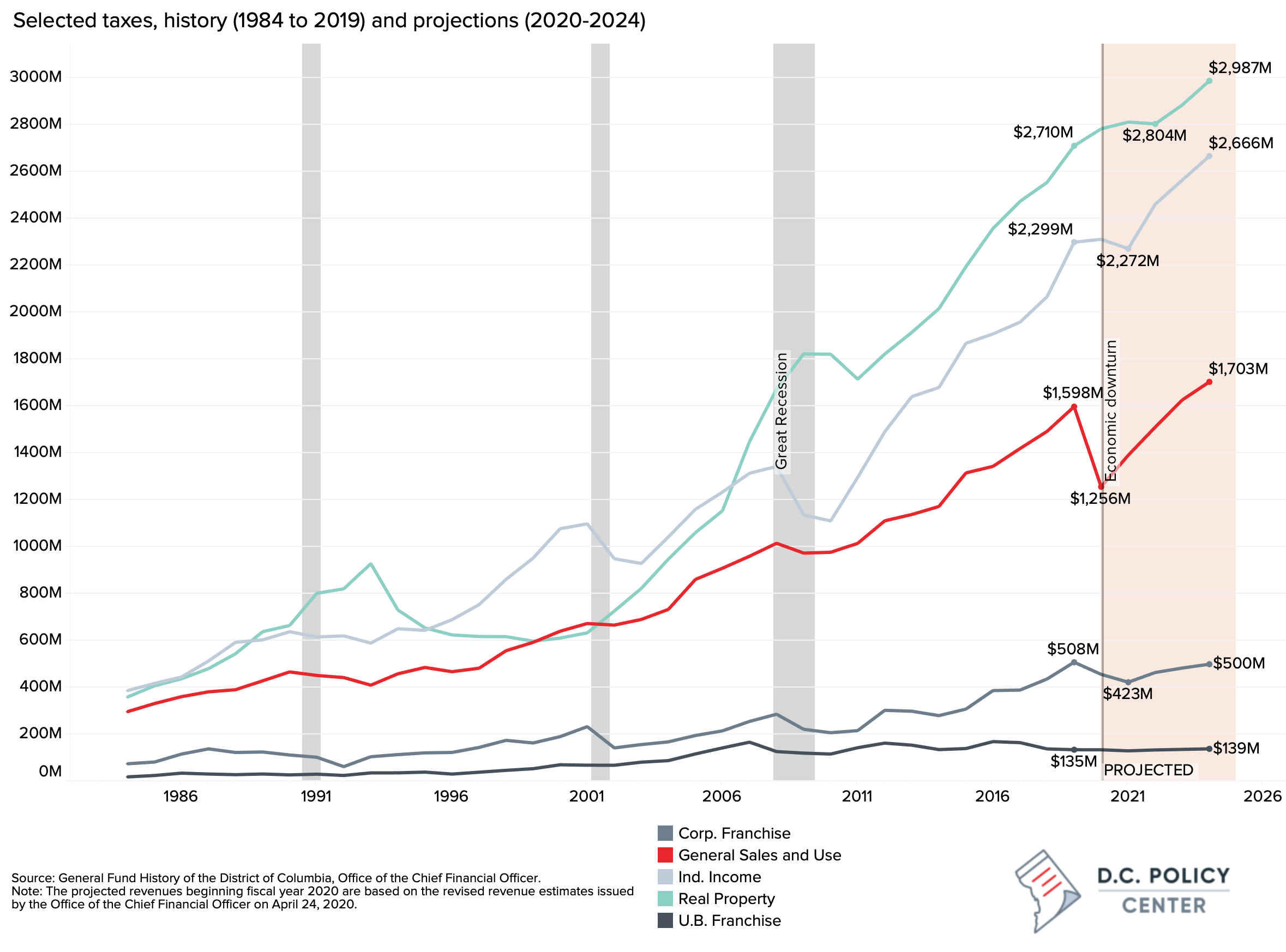

Even though the Great Recession technically began in December of 2007, its impacts on the District’s budget did not become apparent until fiscal year 2009. Between 2003 and 2007, the city’s gross tax revenue had grown, on average, at an annual rate of 7.9 percent, allowing the city to rapidly increase spending. The 5 percent decline in revenues in 2009 and an additional 1 percent decline in 2010 were not just fiscal shocks, but also a shock to the city’s thinking around the budget. In 2009, the city had to redo its budget multiple times—working into the fall months—to close a gap of nearly $300 million. In 2010, the city adopted legislation to safeguard end-of-year surpluses to build rainy-day funds. Since then, the District’s total fund balance increased by $2.1 billion, and its rainy-day funds, by an estimated $800 million.

From a revenue perspective, recovery from the Great Recession came quickly. Gross tax revenue grew by 6.4 percent in fiscal year 2011, and 10.8 percent in 2012. The District’s economy and finances outperformed the rest of the country thanks to a fortuitous confluence of multiple positive factors: increased federal spending and hiring and growing resident employment kept economic losses at bay. When the rest of the country was experiencing high levels of unemployment, the District added 8,200 jobs, and 25,000 new residents including 16,000 working adults. As a result, personal incomes (adjusted for inflation) grew by an annualized 2.1 percent even through the recessionary years (2007 to 2010 in the following chart).

Even with a cure or a vaccine, we will not likely see such a rapid recovery this time around. The pandemic hit at a time when labor market indicators were already showing signs of relative weakness. The District’s annual population growth has slowed to 0.6 percent in 2020, compared to an annualized 1.8 percent through the Great Recession, and an annualized 2.2 percent between 2011 and 2015. Further, the city is no longer experiencing strong net domestic in-migration, which, during the Great Recession and the following recovery, added working and taxpaying adults to its resident labor force. This, in turn, impacts personal incomes earned in the city. Between 2011 and 2015, the District’s total personal income grew on average at 4.1 percent each year. Between 2016 and 2019, that rate was halved.

Current economic projections are fraught with uncertainty.

The negative revenue impacts from COVID-19 are expected to spread from sales taxes in fiscal year 2020 (loss of activity in hotels, restaurants, and retail), to income taxes in fiscal year 2021 (lower stock market performance), to real estate markets in fiscal year 2022 (due to a two-year delay between economic activity in the real estate sector and the time when taxes are paid on this activity). But under current projections, commuters are expected to return; leisure, hospitality and retail are projected to gradually improve; new leases and renewals will be executed protecting operating revenue for landlords; and personal incomes will continue their growth much in the same way as before following a stronger stock market performance and growing employment; all of which brings the city back to a slightly leaner version of its former self by fiscal year 2023.

While the revenue projections predict a slow recovery beginning 2022, they are also fraught with uncertainties. A second wave of infections, a depressed stock market, longer-term closures and social distancing, or a combination of these can disrupt the social economy and commercial lease activity, thereby prolonging the negative impacts on revenue.

Personal income taxes:

The (relatively) bright spot in the revenue estimates is personal income taxes. According to the April revisions, the recession’s impacts will not be entirely felt until fiscal year 2021, when the capital losses associated with a declining stock market in 2020 will be fully realized. That year, personal income tax collections will decline marginally, but then are expected to take off, growing at or above 7 percent for each of the next two years. Overall, personal incomes are expected to decline by about 6 percent through 2020 and 2021 (combined). And, importantly, because most job losses have been limited to low-paying jobs, these losses are not expected to translate into major revenue losses for the District.

The immediate risk to revenue is the stock market performance, which can profoundly lower income that is taxable even when overall personal income remains relatively stable. During the Great Recession, when job losses were relatively modest and personal incomes held steady with the growing resident employment, personal income tax collections declined by 10 percent, largely because of stock market declines. We have no idea where the stock market will end the year or what it will look like through 2021; but we can expect, with some reasonable confidence, that it will be volatile. Current projections foresee a 15 percent decline by the end of 2020, followed by a quick come-back. However, if these losses are greater in 2020, or stock market losses continue into 2021, income tax revenue will further fall.

Corporate and unincorporated franchise taxes:

Corporate income taxes, which generated about $508 million of revenue in 2019, are projected to decline by 17 percent ($85 million) by fiscal year 2021, and then gradually improve over the remainder of the financial plan period, but not enough to make up for all the losses. These losses can be somewhat curtailed if the stock market performs better than expected; or they could be amplified if the crisis leads to widespread bankruptcies (as we have begun to see in the retail sector), or add stress to financial markets, making it more difficult to raise debt or equity. Unincorporated business taxes, which raised $135 million in 2019, are expected to decline by about 5 percent through fiscal year 2021, and slowly recover to their pre-pandemic levels by 2024.

Sales taxes:

Half of the District’s sales taxes are generated by hotels, restaurants, and arts and entertainment venues. Accordingly, the impact of the pandemic-induced shutdowns is, timing wise, first felt through this revenue source. Sales taxes are projected to decline by nearly 22 percent (or $342 million) in fiscal year 2020, and gradually increase thereafter, recovering back to their 2019 levels by 2023. The main risk that threatens the sales tax revenue is a second wave of Covid-19 and associated prolonged closings. Even when some establishments shift to online activities, such an adjustments will not make up for lost commuter activity or depressed tourism. On the positive side, national data show a rapid recovery of retail sales in May 2020, reversing some of the losses of March and April, but this reversal is largely bolstered by online sales and sales of building materials and garden supplies.

Real property taxes:

Under current projections, real property tax revenue will continue to grow through fiscal year 2021 (albeit at a slower rate) and will decline mildly in 2022, when tax assessments will reflect the income erosion incurred in 2020. Beginning with fiscal year 2023, growth is expected to go back to its historical levels of about 3 percent each year. These impacts will likely be felt in commercial and multifamily buildings only; single-family residential property will largely be spared.

If income generating capacity of buildings are severely impacted through the pandemic—through dismal occupancy at hotels, a stalled lease activity in commercial office buildings, or missed rents (here and here)—the revenue impacts could be much deeper and come much sooner if more landlords (than what is usually the case, or is anticipated in the revised revenue estimates) successfully appeal their property assessments. Recovery could also be further halted if commuter activity is permanently depressed, and commercial tenants reduce their footprints either by leasing less space or closing shop.

Tax increases will add to budget risks.

A coalition of stakeholders and advocates, led by the Fair Budget Coalition, has circulated various proposals, including revenue initiatives, to raise money for government programs that would support D.C. residents who have been badly hurt by the pandemic-induced economic crisis. Their demands for more funding for childcare, education, health, human services, and homeless services are justified: more funding for these programs would not only ease the pain, but also help with recovery. But their corresponding revenue initiatives carry risks.

One such proposal is a higher tax for higher-income earners. Because of the disparate impact of the pandemic, which hit low-paid workers and communities of color when higher-wage jobs have been largely been spared, this proposal has attracted attention. But, unfortunately, to the extent such proposals depend on higher-income residents, the greater risk they carry, especially through the near term when the stock market is expected to remain volatile. This is because at the top of the income distribution, relatively safe wage and salary earnings are a much smaller part of taxable incomes, and the relatively volatile earnings from the stock market account for a lot.

The most recent data available from the IRS (for tax year 2017) tell us that in that year, total wage and salary income made up 70 percent of all adjusted gross income in the District, compared to 54 percent for those who earned between $500,000 and $1 million and only 28 percent of those who made over $1 million. For these two groups, combined, net capital gains accounted for 21 percent of income, compared to 8 percent across the entire city. That is, the more raised from higher-income households, the larger are be the risks under current stock market conditions. What happened during the Great Recession (and described earlier) perfectly illustrates this point.

During normal times, the stock market risk can be mitigated when other revenue sources are growing; but tying more programs to such a risky source when no other source will likely make up for potential losses should be cause for concern.

Another proposal is to eliminate the Qualified High Technology Company tax incentives that have been on the books since 2000 (in a tighter form since 2015, and further tightened in 2019). These are a collection of tax breaks (corporate taxes, real property taxes, and various credits linked to employment) largely intended for technology start-ups. The costliest part of this initiative is the provision that eliminates corporate tax liabilities for the first five years of profitable operation for an eligible company. While the merits of this policy are subject to debate, the unfavorable business environment under the pandemic, which projects a steep decline in corporate profits, is likely to limit is fiscal impacts.

Some of the other proposals listed in the Fair Budget Coalition document, regardless of their merit, similarly run into pandemic-induced problems. For example, the proposal to require companies that hire gig workers to pay for employee benefits is incredibly important and demands policy attention. But the revenue impact will be limited given the chilling impact of the pandemic on the gig economy. The same limitations apply to the proposal to eliminate capital gains deferrals for investments in Opportunity Zones.

Budget priorities can address structural inequities, but more work is needed.

The Council is troubled by the lack of additional funding in the proposed budget for key services that could help the DC residents most hurt by the pandemic-induced economic downturn. But, given the unknowns about the course of this pandemic, raising taxes to pay for these programs is risky. If the Council has different spending priorities than the Mayor, the more prudent way to advance them is to cut spending elsewhere, and not raise taxes.

The importance of the work necessary to address structural inequities in the District became especially clear when the pandemic amplified the disparities in health, wealth, and well-being of D.C residents. Spending priorities will matter: In particular, undoing inequities and racism requires a long-term strategy that directs the city’s resources to communities that have suffered from historic underinvestment. But this will not be enough. More work is needed to reverse the legal and regulatory barriers that limit opportunities for the lowest income residents and perpetuate historical racism: reforming fines and fees, paring back professional licensing, eliminating restrictive land use regulations, reassessing the tax system with an eye toward racial equity, and eradicating implicit bias to build trust must all be on the table. Economic growth alone, without these systemic changes, will never be enough to permanently erase needs.

Editor’s note: When initially published, the essay incorrectly stated that the Great Recession started in December of 2008. This has now been corrected (December of 2007).