On September 24, 2020, D.C. Policy Center Executive Director Yesim Sayin testified before the Committee on Housing & Neighborhood Revitalization at the public hearing for rent control bills B23-0530, B23-0877, B23-0879, B23-0878. You can read her testimony below, and download it as a pdf here.

Good morning, Chairwoman Bonds and members of the Committee on Housing & Neighborhood Revitalization. My name is Yesim Sayin Taylor and I am the Executive Director of the D.C. Policy Center, an independent, nonpartisan think tank committed to advancing policies for a strong and vibrant economy in the District of Columbia. I thank you for the opportunity to testify on the five bills on rent control this committee is considering.

In April of 2020, the D.C. Policy Center published a comprehensive report on rental housing in the District of Columbia to evaluate its capacity to create economically inclusive neighborhoods. This report provides extensive data on rental apartment buildings including the rent-controlled stock as well as rental units not in rental apartment buildings. My comments today are largely informed by this research and new knowledge the D.C. Policy Center has generated through its extensive study of housing in the District of Columbia.

D.C.’s current rent control laws are relatively successful in balancing tenant protections against provider’s willingness and financial ability to remain in business and maintain and upkeep their buildings.

The underlying tension in rent control policies is balancing the desire to stabilize rents for tenants against the need for the housing providers to turn a reasonable profit from their operations. Unlike housing subsidies, which are paid for by public dollars, rent control laws try to split the economic value created in the rental housing market between tenants and housing providers.

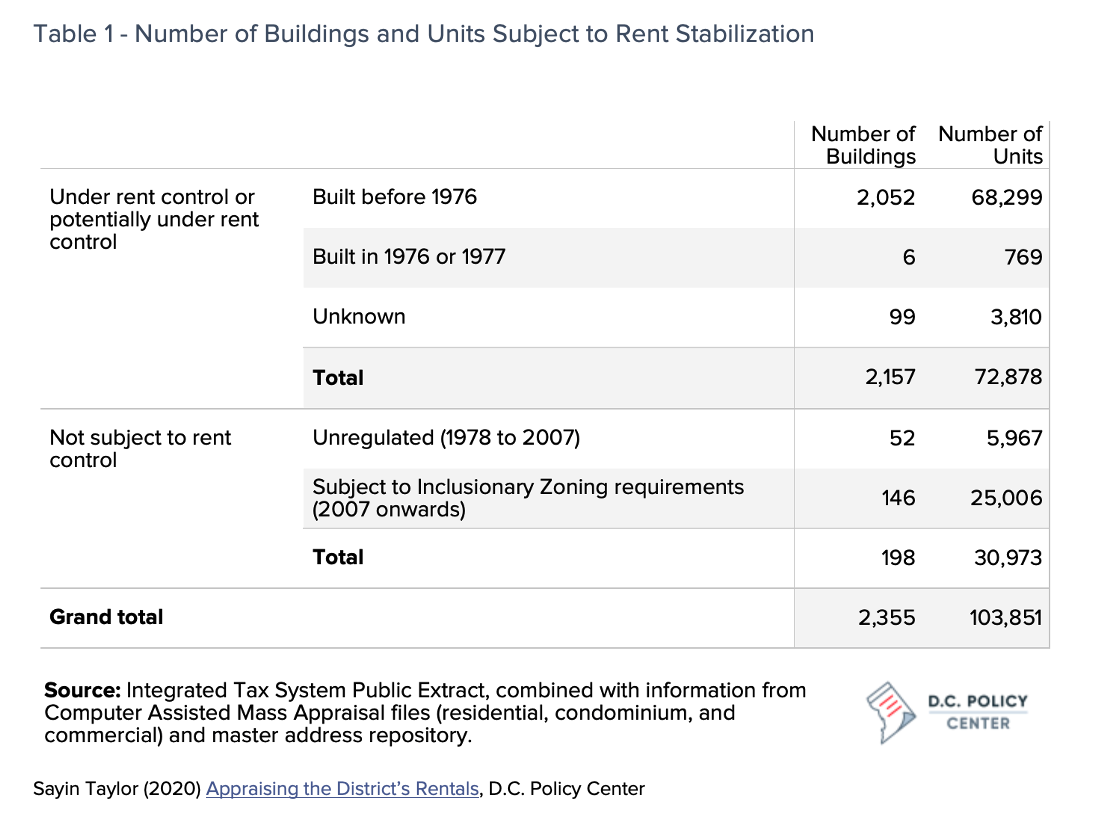

The District’s rent control laws have so far been successful in protecting tenants from opportunistic increases in rents while allowing providers to make enough of a return on their investment to keep their units in the rent-controlled stock. Over 35 years after the enactment of the Rental Housing Act, the number of rent-controlled units in D.C. has held up relatively well. We estimate that D.C. currently has close to 73,000 rent-controlled units spread across 2,150 separate buildings (excluding public housing and other subsidized units, see Table 1).[1] This represents a loss of somewhere between 15 percent to 30 percent of the rent-controlled stock since when the law was passed.[2] This is a much lower loss rate than other jurisdictions with stricter rent-control policies.[3]

The five proposed bills amount to a presumption on the part of the D.C. Council that housing providers can absorb monetary losses.

The five bills on hand are modifying various provisions of the rent control laws including eligibility, rent increase provisions, and various petition processes that housing providers could use to recoup the cost of large investments necessary to maintain and upgrade their units and buildings. Collectively, these five bills amount to a large bet on the part of the D.C. Council that providers can absorb the monetary losses and continue to make a meaningful return on their investments. Our research shows that this presumption could be incorrect.

I will first offer brief observations about each of the five bills, and then conclude with overarching remarks.

The Rent Concession Amendment Act offers an arbitrary definition for concessions.

Bill 23-237, the “Rent Concession Amendment Act of 2019” limits the concessions offered by landlords to 90 percent of the base rent for units under rent control. It also requires that when advertising a unit, the housing provider must disclose the base rent, the surcharges, and when offered, the discounts on the rent for an introductory period, commonly known as concessions. Finally, it limits the providers to a 30-day window following the anniversary of a lease to implement leases allowable by law. If a provider delays rent increases for other reasons, then the provider would have to forgo this increase so long as the same tenant occupies the unit.

The disclosure requirements in this bill are admirable and should be enacted. No tenant should be misled about their rent. But the rest of the provisions of the bill presumes an amount of knowledge about market conditions on the part of the District government that is neither real nor reasonable. The amount of concessions offered by each landlord reflects the unique conditions in each building, including vacancy rates. Similarly, while providers remain limited to a one-time rent increase each year, timing of the rent increase should depend on market conditions as well as vacancies in each building. The housing providers are in a better position to determine the appropriate discount to get their units occupied as well as the timing of the rent increase.

We urge the Council to adopt the disclosure rules but reject the limitations on the amount of concessions and timing of rent increases.

The Rent Stabilization Affordability Qualification Amendment Act will favor small and affluent households over lower-income families.

Bill 23-0530, the “Rent Stabilization Affordability Qualification Amendment Act of 2020” limits eligibility for rent controlled units to those renters who earn less than five times the monthly rent charged for the unit. At present, rent controlled units have no income targets.

This provision will make it harder for lower-middle income households with multiple members to find rental units in the rent-controlled stock and instead favor younger, more affluent renters of smaller households.

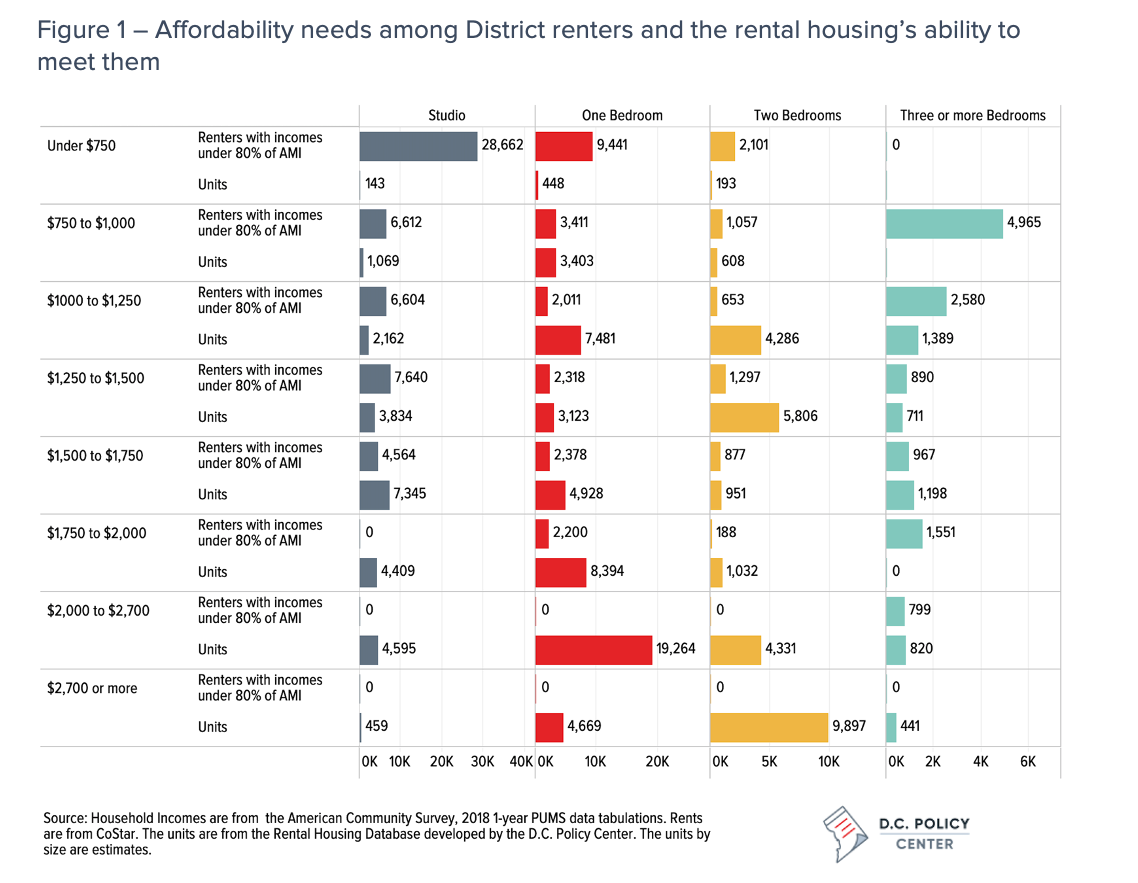

To see this, imagine a two-bedroom unit that rents for $1,500 per month. Under the proposal, a single-person household with a $90,000 annual income (102 percent of Area Median Income) will be eligible to rent this unit, but a family of four with a $91,000 annual income (72 percent of Area Median Income) will not. And this is not a rare problem in D.C. The median income of incomes of two person households in D.C. are about the same as the median income of a four-person household. The relatively affluent singles and couples have always put pressure on the District’s housing market as we have shown in our previous research,[4] and this provision will amplify their pressure on the rent-controlled stock (See Figure 1 at the Appendix) We urge the Council to reject this proposal.

The Substantial Rehabilitation Petition Reform Amendment Act could create an unfunded mandate for providing affordable housing that could cost $6,610 on average per rent-controlled unit.

Bill 23-0877, the “Substantial Rehabilitation Petition Reform Amendment Act of 2020” will reduce the present value of rent surcharges that housing providers could implement to recoup the costs associated with substantial improvements that cost more than half the assessed value of their building. The providers are directed to spread rent increases over 27.5 years. Additionally, housing providers are directed to pass on any savings from energy efficiency investments that result from their investments. Importantly, the providers would have to meet or exceed Green Communities certification requirements,[5] which specifically require rental apartment buildings to serve residents at or below 60 percent of Area Median Income.

The impact of this bill would be fewer substantial rehabilitations—an undesirable outcome for the health of rental housing in the District and for the tenants that occupy them. Further, the requirement that the rehabilitation should meet Green Communities certification standards is confusing and could imply that rent controlled buildings would have to limit their tenants to 60 percent of Area Median Income. If this is indeed the case then this bill will result in a rapid pace of condominium conversions in the city.

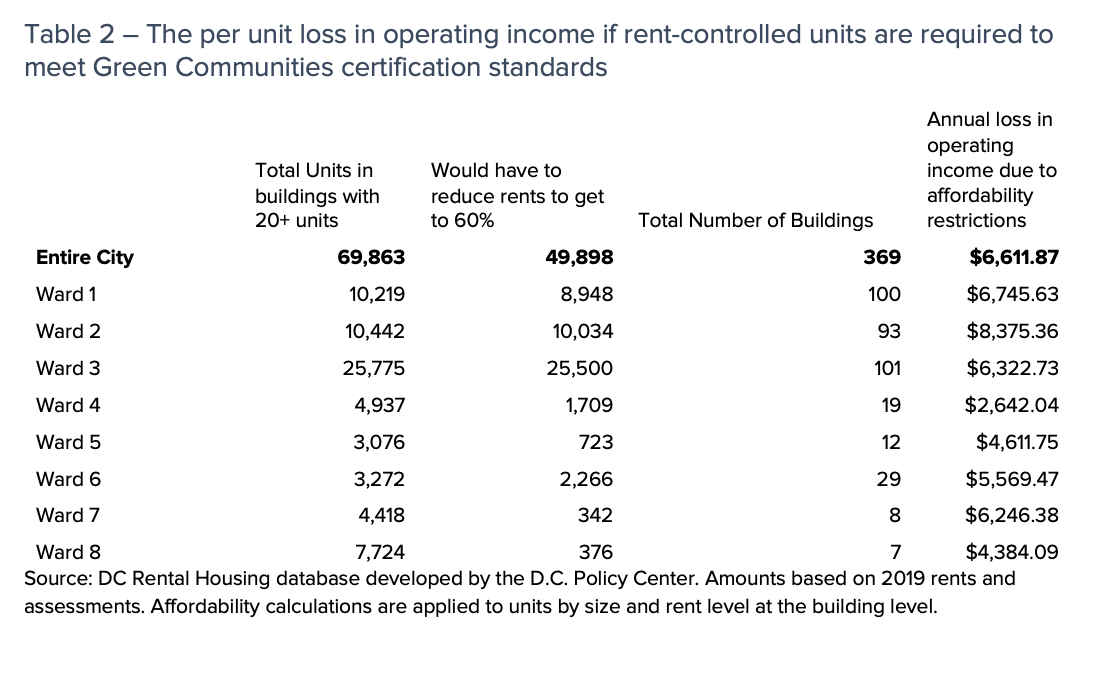

If providers are required to serve tenants with at most 60 percent of Area Median Income, many would have to reduce their rents.[6] Given the prevailing rents, we estimate that operating revenues, on average, would have to decline by an estimated $6,611 per unit, and by higher amounts in certain Wards (See Table 2).[7] For a building with 135 units,[8] this is the equivalent of $898,000 loss in operating revenue per year. It also translates into a reduction of approximately $16 million in the assessed value of the building and an associated loss of $132,000 in tax revenue (assumed cap rate of 5.75%). Alternatively, if the city supported the full cost of rehabilitation through a HPTF loan for 30 years, in return for a 50 year covenant to limit rents at levels affordable at 60 percent of Area Median Income, the city would have to spend $108,000 per unit, or provide a loan of $14.6 million to pay for the project.

When facing such a monetary loss, at least some landlords will try to convert their buildings into condominiums to escape this cost; others, perhaps blocked by TOPA, could find that the most financially sound option is to let their units decay. And research shows that if this happens larger providers with access to capital will likely to take their units (or investment out) while smaller providers, with fewer options, will likely stay and try to bear these costs.[9]

We urge the Council to clarify whether the bill intends the use of Green Communities certification in this manner.

The Capital Improvement Petition Reform Act can further disincentivize the maintenance and improvement of rent controlled units and buildings.

Bill 23-879, the “Capital Improvement Petition Reform Amendment Act of 2020” similarly imposes limits on how much landlords can recoup, and over what period of time, if they invest in capital improvements that are not large enough to qualify as “substantial rehabilitations.” The bill specifically directs the housing providers to spread the cost of capital improvements over 27.5 years, thereby reducing the temporary surcharge they can impose on the rent. At present, the landlords can spread these surcharges over up to 8 years, and sometimes shorter (for smaller projects).

Were providers able to borrow to pay for these costs through loans of similar life span, this provision would have been less problematic. But some providers rely on shorter term loans (or more frequent refinancing) to pay for the costs of capital improvements. The bill would require landlords to absorb the difference between their loan repayment and the income they collect from surcharges. While we do not know how many landlords would delay or forgo a capital improvement, fewer investments will happen under the provisions of this law.

The Voluntary Agreements Moratorium Act could potentially discourage investments in the rent-controlled buildings without any attempt to solve a stated problem.

Bill 23-0878, the “Voluntary Agreement Moratorium Act of 2020” would impose a two-year moratorium on voluntary agreements. Voluntary agreements allow housing providers to increase rents in return for specified improvements in services and amenities available to tenants. 70 percent of the tenants must sign the agreement before the provider can submit the petition.

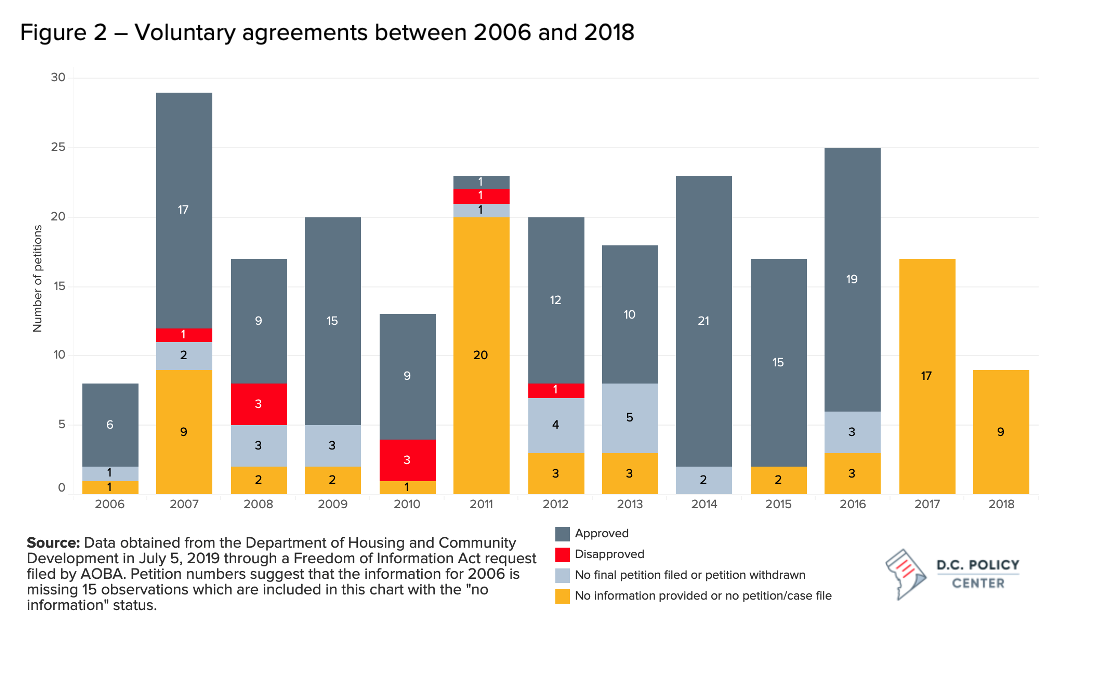

According to the Department of Housing and Community Development, voluntary agreements are rare. The city receives somewhere between 10 and 30 such petitions each year (including some single-family homes), which represents somewhere between 0.4 percent to 1 percent of all the buildings covered by the rent control law (Figure 2). Among the 167 petitions where it was possible to track an outcome, 80 percent of the voluntary agreements were approved, about 5 percent were rejected, and 15 percent did not move forward.

Voluntary agreements have received some bad press. But they have also made investments in rent-controlled buildings possible. The option of being able to adjust rents (with support from the tenants), when it is necessary to update amenities and services in a building, keeps investor interest in rent-controlled buildings alive.

If the Council’s goal is to maintain the size of the city’s rent-stabilized stock, the answer is to relax the rules that govern rent increases, not tighten them.

The closer rents are to market rate, the more likely that housing providers will maintain their investments in these buildings, and the lower the temptation to take them out of the rental market entirely by converting them into condominiums.

In contrast, further restricting housing provider income will frustrate the District’s affordability goals. The city has firsthand experience with how expensive affordability can be: The District provides substantial subsidies for the creation and preservation of affordable housing units in addition to a combination of federal and local rent subsidies. These, when combined, account for more than $150 million in the District’s annual budget. If the District were to go beyond an extension of the current rent stabilization law and enact stricter rent control laws, absent any other supports, the city would simply push the cost of subsidizing affordability from the government’s balance sheet to landlords’ balance sheets—creating what is essentially an unfunded mandate. And the market will not passively internalize this, and the mostly likely outcome will be fewer, and not more, rent-restricted units.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify. I am happy to answer any questions you might have.