By Will Handsfield, Transportation Director, Georgetown BID

The D.C. Policy Center recently published an analysis of the Georgetown-Rosslyn Gondola by independent research fellow Alon Levy. The Georgetown BID, along with other partners, serves on the Executive Committee of the group exploring this project. And we disagree with certain arguments raised in the article.

Let me begin with a quick summary of the project and our findings from a technical feasibility study we commissioned.

Rosslyn Gondola Station Concept by ZGF Architects, Base image: JBG / Central Place and Cliff Garten Studio

What will the Georgetown-Rosslyn Gondola look like?

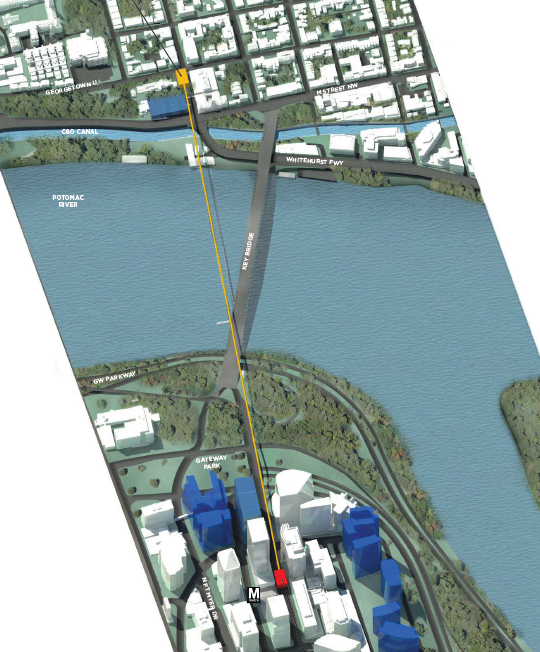

The Georgetown-Rosslyn Gondola project[1] would install an aerial lift gondola from a station at 36th Street between M Street and Prospect Street to a station in Rosslyn located above N. Lynn Street at the Metro Plaza. The fare system and rates would be integrated with the region’s system—that is, riders would be able pay for it using their SmarTrip cards.[2]

The project completed a feasibility study in 2016 with the following findings:

- The Gondola is technically feasible and is eligible to secure the permits necessary for construction;

- The most promising alignment for the line is from 36th Street to N. Lynn Street.

- The Gondola is projected to have a minimum weekday daily ridership of 6,500 riders;

- The project will cost an estimated $80-$100 million[3] to construct, similar to other gondola systems around the globe;

- The project will have $3.25 million per year operating costs – similar to other gondola systems;

- The estimated cost per ride is significantly lower than other public transit modes with similar performance; and

- Once in place, the gondola will induce new regional public transit trips and may reduce some car trips.

Proposed gondola stations and alignment (planned buildings in blue)

Let me now turn to the concerns raised by Mr. Levy and address them in the order of importance:

Concern: There isn’t much work travel demand between Georgetown and Arlington.

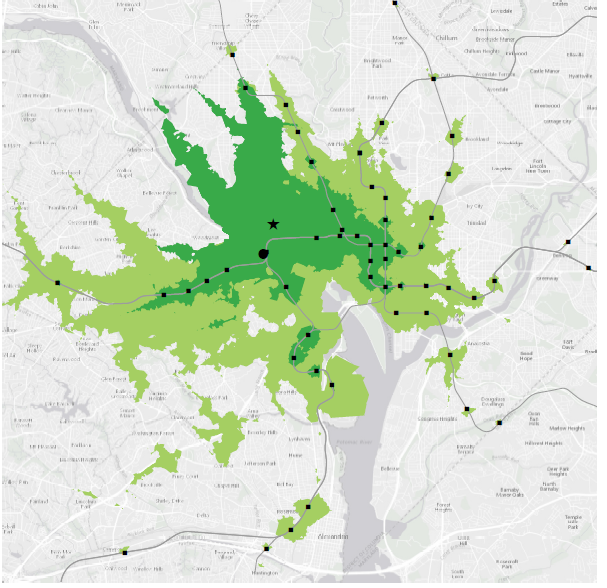

Our response: Instead of only considering work travel demand between Georgetown and Arlington, we need to look at the broader commuting flows into Georgetown. This is because the purpose of the gondola connecting to the Rosslyn Metro Station is not to provide a single-leg trip to those who happen to live in Arlington and work in Georgetown. The Gondola will provide anyone within the Metro catchment area a faster trip to Georgetown. With the Gondola, the total travel time to Georgetown drops to less than 30 minutes for a much larger part of the region, including areas of the District with the greatest need for employment opportunities, giving them a faster way to connect with jobs in Georgetown.

30 minute transit times to Georgetown today (dark green) and with future gondola (light green). Metro lines & stations shown

Our own numbers derived from payroll information show that between the Georgetown University and the commercial sector, Georgetown is home to 22,000 jobs. This count does not include individuals employed in Georgetown’s households or doing service calls in the area.[4]

Furthermore, employment data does not capture the totality of trip demand to or from Georgetown, which is a bustling destination for locals and tourists well beyond the traditional workday. In fact, our weekend pedestrian counts can be triple what they are on weekdays[5]. Our comprehensive ridership model–prepared by Fehr & Peers –therefore looks at land-use, employment, and trip generation attributes of Georgetown, Rosslyn, and the additional parts of the Metro system that would be accessible within 30 minutes if there were a gondola that links Georgetown to Rosslyn station. Fehr & Peers combine these attributes with the regional MWCOG model to estimate that 6,000 to 15,000 riders would use the Gondola per day. We think 6,500 riders per day is a solid, conservative estimate for usage.

Concern: The station on the District side wouldn’t be sufficiently integrated into the local public transit network and would only be convenient for Georgetown University students, and not many others.

Our response: The station at 36th and M is envisioned to connect to existing bus routes, and the Circulator would modify two routes to serve this station: the crosstown to Union Station and the Rosslyn/Dupont routes would instead be “Car Barn” terminal routes, while the current Georgetown shuttle (GUTS) from GU to Rosslyn Metro would be discontinued and replaced by the Gondola. The latter change alone would lead to about 1,900 daily riders for the gondola. In addition, the 38B, and other 30 series buses could be reconfigured to serve this location. Even relying on existing stops, it is a direct two block walk to 34th/M Street, the same distance as the current Circulator stop is from the Rosslyn Metro. The project proponents also envision a significant bike parking area at the Georgetown station, similar to what is in place at the Portland Air Tram’s lower terminal.

Portland Air Tram Bike Parking – Image by Steven Vance via Flickr, Creative Commons License

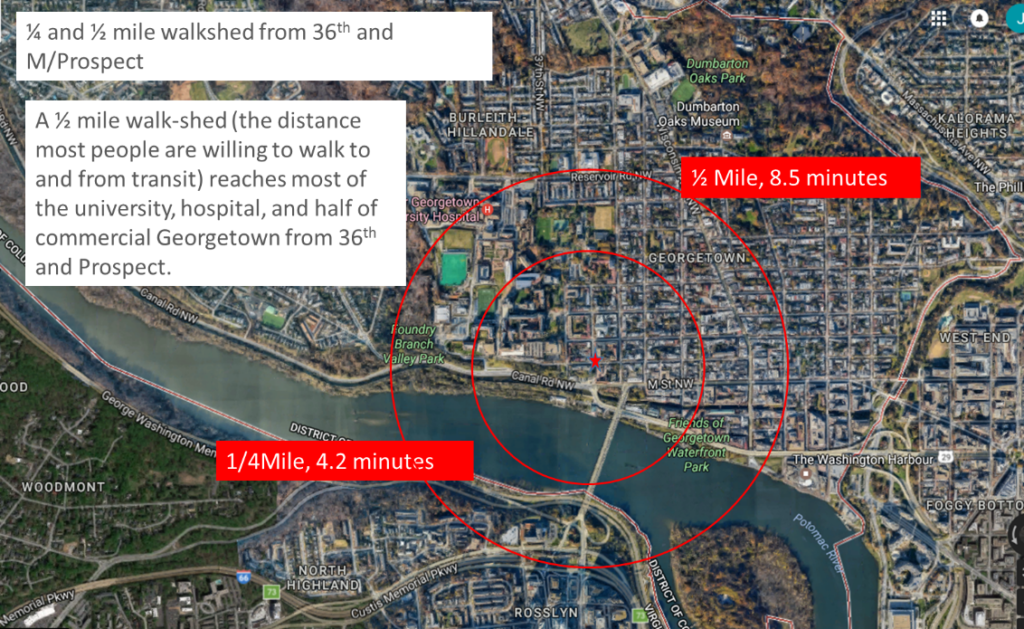

On foot, this station would be very walkable from most of Georgetown via the station entrances at Prospect Street and M Street, and very accessible to much of the commercial area. At walking speed from the station, it would take under 9 minutes to reach Wisconsin and M Street, 9 minutes to Medstar hospital, or 14.5 minutes to reach Book Hill Park.

Quarter- and half-mile walkshed radii from the Georgetown Gondola Station.

Current planning[6] also suggests the re-use of the Glen Echo trolley trail as a multi-use path, which could serve open up neighborhoods west of the University to the gondola station and transit access with a short walk or bike ride. In total, the future station would be well-integrated with the surface transit network. As it stands, the proposed station location is highly accessible to roughly 14,500 employees of the University and western part of the commercial area,[7] along with another 12,000 residents of the area (including students)[8].

Concern: The gondola wouldn’t necessarily save passengers much time over walking, and many people would have a faster time walking to Foggy Bottom.

Our response: “Why can’t people just walk?” is a common criticism we hear. The reality is that today, about 10 to 12 percent of our employee population walks to work in Georgetown and a good portion of that is from the nearby Metro stations. Research on the subject (you can review MWCOG’s work here and a widely used Berkeley study here) suggests that when faced with a walk of a mile or more after exiting their transit station, less than 12 percent of our total employee population is willing to use public transportation for their commute. Given what we know about preferences for walking to or from a transit station, with access to a gondola station at 36th & M/Prospect, around 40 percent of our employee population would be willing to take transit to work. That is a significant difference!

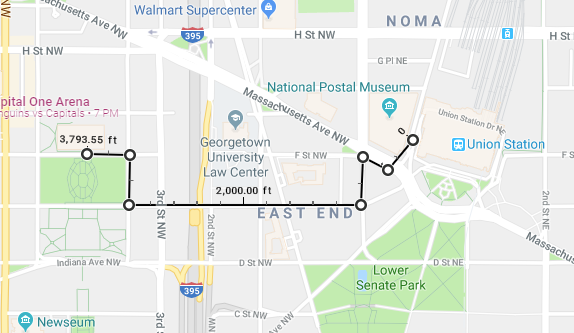

Georgetown Station Massing & Access Study – ZGF Architects

We also must respectfully disagree on the travel time; we have tested it, walked it, timed it, and are extremely confident in our findings, which show that the gondola would be a significant time-saver for many Georgetown commuters compared to existing options. As a comparable thought exercise, imagine taking Judiciary Square out of service on the red line, and requiring thousands of people who work in the area or use the station to instead walk from Union Station. That is also around a 3,700-foot walk, but it really changes how you think about getting there without the direct and proximate transit access.

Image created with Google Maps

A feature known, but harder to quantify, is that the nature of the walk matters a lot, and we have reviewed much of the Center for Neighborhood Technology’s work on walkability in this context. They consider western Georgetown an area with a strong transit market, but significant transit gaps. Simultaneously, Georgetown has a Walk Score ranging between 90 and 100, among the highest possible. It is currently a brisk 16-minute walk from Rosslyn Metro to the edge of the Key Bridge in Georgetown, compared to four minutes for the same distance on the gondola from platform to platform. If you wanted to walk to Prospect Street after crossing Key Bridge, add another four to six minutes and a 60-foot stair climb – the gondola station would have an escalator that would get you there 30 seconds after de-boarding. We know people are willing to walk a little further to transit if the experience on foot is great[9], and there is no question that Georgetown is a wonderful and interesting place to walk—so we are confident more people would make trips from beyond that half-mile ring.

Gondola Station North Entrance area at 36th & Prospect, very walkable. Image created with Google Streetview

The bridge walk is a different story: while beautiful, it is not always pleasant. It is often stormy, icy, windy, very hot, or very cold—all conditions in which a gondola ride would seem more appealing. Crossing from Georgetown to Arlington on foot also requires crossing intersections of Lee Highway, GW Parkway off-ramps, and busy surface streets to reach the Metro entrance. Local cyclists use the term “intersection of doom” to describe this area, to give a sense of the ground-level experience.

A section of the “Intersection Of Doom” looking north towards Georgetown. Image created with Google Street View

Similarly, the walk to Foggy Bottom, depending on the route, takes around 15 minutes from the eastern edge of Georgetown, or 25 or 30 minutes from Wisconsin and M Street, and includes some fairly hostile conditions for pedestrians, such as the K St/ 27th Intersection and surrounding environment.

The walking route from eastern Georgetown to Foggy Bottom Metro. Image created with Google Streetview

Concern: While relatively few Metro riders would elect to use the gondola between Georgetown and Rosslyn, they would nonetheless overload the rail network.

Our response: If the gondola would serve so few Metro riders, how could they overload the rail network? That contradiction aside, it’s hard to believe that Rosslyn Metro is so busy it can’t take any more riders. It is a very busy station, partly from inter-train transfers, but many of the trips the gondola would facilitate would be from the eastern side of the District. Today, trains headed west from Foggy Bottom to Rosslyn at morning rush hour are frequently less than half-full, and vice versa at the evening rush, as you would expect on trains servicing the core. While the latest train capacity reports for Orange/Blue/Silver line haven’t been published yet, we are confident the additional passengers delivered into the rail system by the gondola would find room on the trains. In addition, not every one of them is going to be an in-bound D.C. passenger: Many will need to head to an airport, or destinations south or west. It’s clear that the gondola would be a real and useful interconnection with the rail system.

Besides the arguments against our specific project, Mr. Levy made many statements about gondolas generally that we believe are inaccurate:

Myth #1: The costs are akin to light rail per mile.

Our response: Because this project spans the Potomac River, it’s unfair to make a direct mileage comparison between the gondola and light rail. In stating that the costs would be similar per mile, Mr. Levy is either assuming a rail line could and would displace other modes from the existing bridge, or that a new tunnel would be built. However, cost per mile isn’t the right metric to use—cost per rider gets closer to what matters for transit. In this case, the estimated 6,500 daily riders result in a cost per rider of less than one dollar, among the lowest cost per rider of any system in the region.

Myth #2: The average speed of gondolas is low (11-13.5 miles per hour).

Our response: Gondolas compare favorably against the actual speed of buses or streetcars operating on urban roadway networks (8- 12 MPH in DC), and are near the average speed of subway and light rail (13.5 MPH) when you account for the time stopped at stations[10]. The nature of gondolas is fairly different than other fixed-guideway transit, since the cabins are continuously moving through the stations, and the time in between cabins can be as little as 12 seconds. The most recently built gondola systems have a cable speed of 13.5 miles per hour, while the real speed of buses crossing the Key Bridge corridor is two to five miles per hour. This is because the Key Bridge is a persistent bottleneck in the transportation network—as bridges often are—and suffers from significant daily congestion. The travel time for the Circulator, GUTS, and Metro buses for the same segment is 12 to 30 minutes[11], depending on roadway conditions, versus a consistent four-minute trip on a gondola from platform to platform.

Myth #3: The capacity of gondolas is limited.

Our response: The system we have sketched out, with 23 cabins that will each hold a maximum of 12 passengers, could carry 2,400 passengers per hour, per direction—or 4,800 total passengers per hour. It is true that heavy rail can carry more, but the system has tremendous capacity for the cost, which makes the comparison to a 100-passenger streetcar simply inaccurate.

Myth #4: While costs appear comparable to light rail, it isn’t as easy to build gondolas since the scale of urban rail is larger than what gondolas can serve.

Our response: Mr. Levy is incorrect about the costs being anywhere close to light rail—specifically for the particular leg we are considering, which is between two palisades overlooking a river. He is also wrong about ease, and time for construction. We estimate the gondola would be constructed in 18 months, a relatively short duration for a mass-transit project – as an example, the recently opened Mexico City system was built and commissioned in 18 months.

Myth #5: They are only useful in high mountain areas where conventional road and rail systems would be circuitous.

Our response: Mr. Levy’s implication, via omission, is that the places that use gondolas successfully (i.e. Mexico City, Medellin) are mountainous, but that those geographic challenges aren’t present with this system. While some of the more notable systems have been installed in mountainous areas, many systems cross rivers, which is one of three primary geographic features gondolas excel at crossing (steep slopes, canyons, bodies of water) compared to other transit modes. The systems in Wroclaw, Poland; Koblenz, Germany; and Nizhny Novgorod, Russia were built just to cross rivers. Similarly, the system in Singapore crosses a harbor. Mexico City’s system, to be clear, runs through a relatively flat valley with tremendous density.

Mr. Levy concludes by saying gondolas are a poor fit for Georgetown’s needs, and argues that the area really needs a Metrorail connection. On this, we agree! But here is where context, timing, and cost matter. A 2014 estimate found that the costs for the separated Blue Line project that would build two Metro Stations in Georgetown would be $12.5 billion ($2.5 billion just for Rosslyn and Georgetown portions), with a construction time between 10 and 14 years.

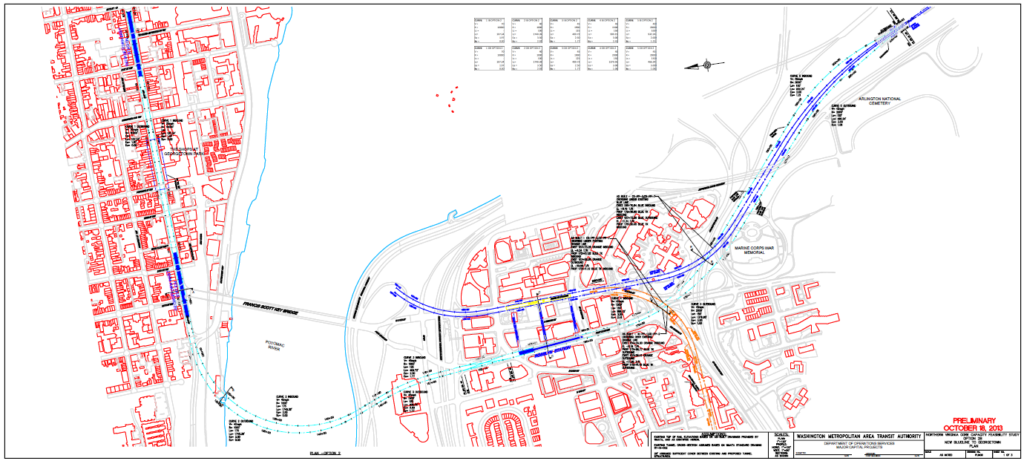

Preliminary Engineering Diagram of Separated Blue Line (light blue) from Rosslyn through Georgetown, WMATA – 2014

By contrast, the gondola could deliver a high-capacity transit hub to western Georgetown, covering the entire University campus and over 50 percent of the commercial district in a half-mile walkshed radius, with a $100 million project that takes 18 months to construct following permitting. It has taken the region 40 years to provide $15.5 billion in dedicated funding to maintain Metro, and it is difficult to estimate when another $12.5 billion will be identified for the separated Blue Line project.

The case is quite clear that the Georgetown-Rosslyn Gondola would be a wise investment for the region, and should build with all possible urgency. We welcome further discussion on the merits of the gondola and the details of its implementation, but we need to start at a point of accurately understanding the capabilities of gondola systems, as well as the specific geographic and sociographic features for the project in question.

Rosslyn Gondola Station Concept by ZGF Architects, Base image: JBG / Central Place and Cliff Garten Studio

Notes

[1] A more detailed presentation on the project is available here (PDF).

[2] For Metro riders who are ending or beginning a trip in Georgetown, the crossing would simply be calculated as an additional stop on the Metro system. For riders who are only using the gondola to cross the river, there will be a single one-trip fare developed that is likely to approximate a single stop Metro fare – currently between $2.00 and $2.25. http://www.georgetownrosslyngondola.com/faqs/

[3] We have updated the estimate since the 2016 feasibility study to account for inflation and the increased cost of land acquisition.

[4] The BID’s economic statistics, derived from DOES via the quarterly census of payroll and wages and payroll data from Georgetown University, indicate that in 2017, there were 21,921 paid jobs in the Georgetown BID’s geographical area.

[5] Georgetown BID pedestrian counts collected using Eco-Counter hardware and software.

[6] The MoveDC plan shows the Glen Echo trolley trail as a future multi-use trail. There is great demand from cyclists from Ward 3 to begin developing the trail. Finally, the trail is also in the Georgetown University’s Zoning Approval Order of its 2017 to 2036 Campus Plan.

[7] This estimate includes all of Georgetown University employees and half the commercial employees in Georgetown.

[8] Derived from Georgetown University data and Georgetown BID data available in The State Of Georgetown 2016 Report. The estimate includes the University’s residential population, and one third of the residential population of Georgetown, or the population approximately the size of West Village.

[9] The researchers in this field have a harder time pinpointing the qualitative features that make a place more “walkable,” and applying quantitative outcomes like “how many more people will walk somewhere if it’s a nice walk?”, but it’s clear that walkability has a positive effect on rates of walking.

[10] My regular trip from Foggy Bottom to Stadium Armory takes 22 minutes to travel 5 miles, or 13.5 MPH through the densest section of the Orange/Blue/Silver line route.

[11] Georgetown BID and ZGF Architects travel time logs.

Guest contributor Will Handsfield is the transportation director for the Georgetown Business Improvement District, and has worked on transportation projects in Los Angeles, Denver, and the metropolitan Washington region.