Business migration trends offer important insights on regional dynamics. While the Washington metropolitan area shares a labor force and many economic strengths, D.C. has, on net, lost businesses to elsewhere in the region. And, though D.C. is strongest at attracting small, young firms, it is still a net exporter of these businesses. This can be an indicator of what businesses are lacking in D.C. and feel that they can get elsewhere. Businesses move for a variety of reasons, but it is possible that these firms need to operate in different environments as they begin to mature, or that they grow out of the city as they hire more employees and increase sales. In the future, a better understanding of why businesses move will be central to D.C.’s future economic success, especially as economic activity has become more dispersed.

The District of Columbia is surrounded by increasingly competitive jurisdictions. As a result, residents, workers, and employers have many options when choosing where to live, work, and set up shop. A jurisdiction’s economic conditions and government policies can influence business performance. And, what works for a business when it is just getting started may no longer work when it is well established. A better understanding of the migration of businesses within the region is central to D.C.’s future economic success, especially in a time when economic activity has become more dispersed, making central cities less important.

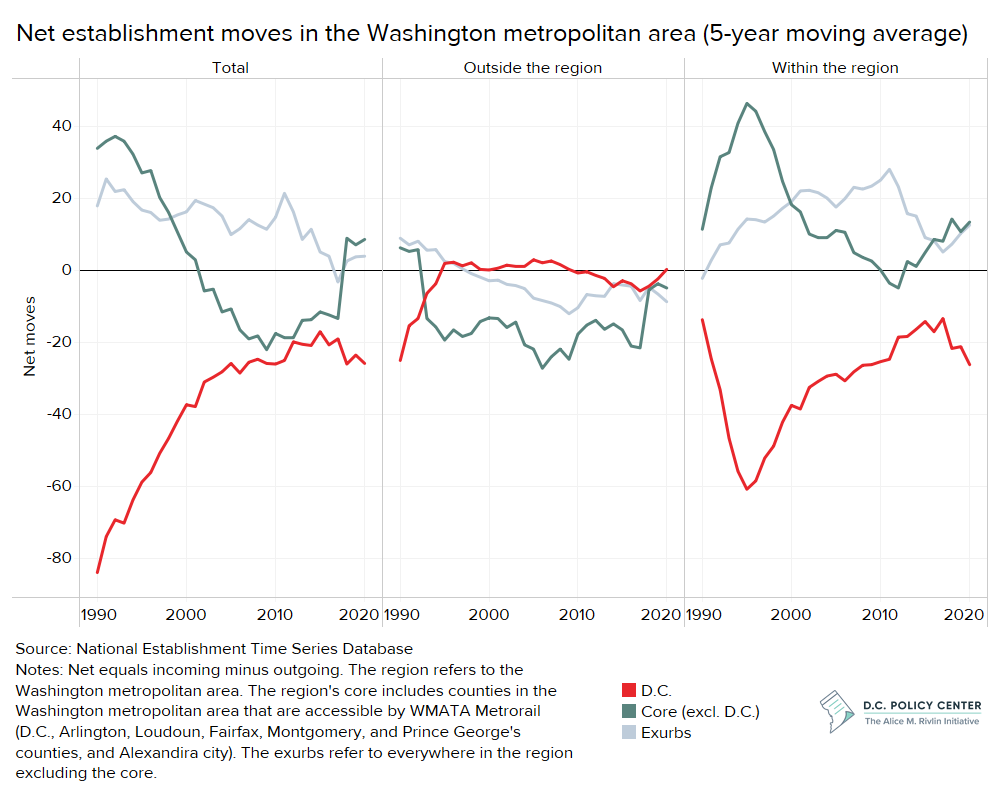

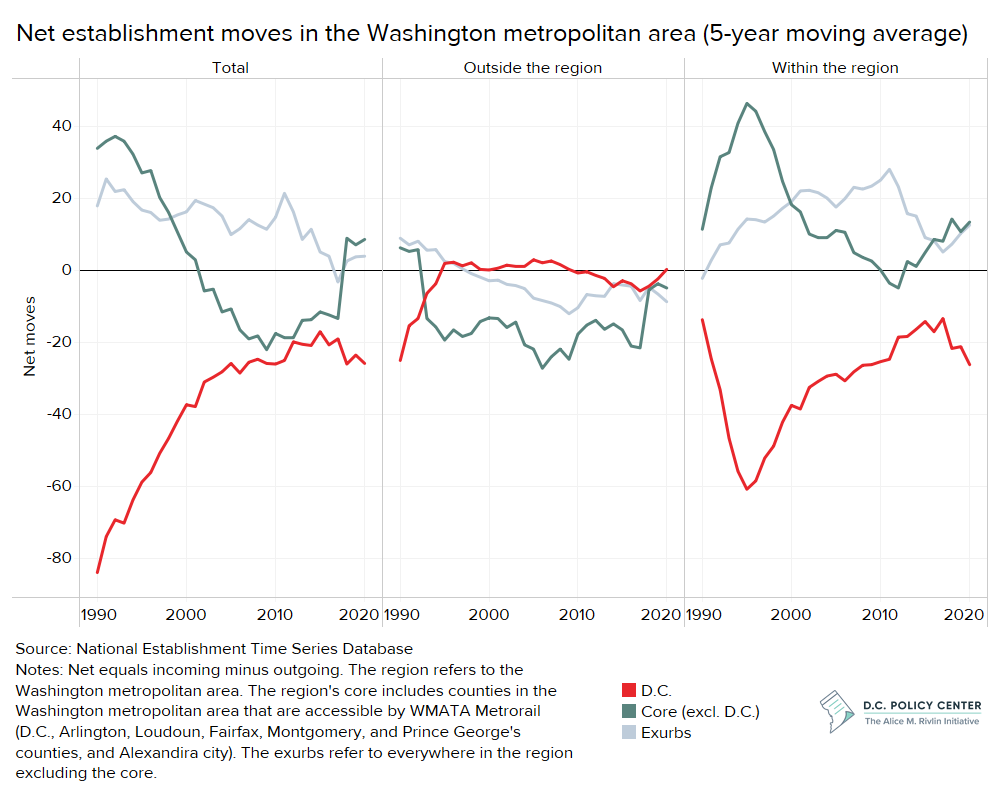

#1. D.C. has always been a net exporter of businesses.

Between 1990 and 2019, for every 1 business that moved to D.C., 1.7 moved out.1 As a result, D.C. was also exporting jobs. For every 10 jobs that came with a business that relocated to the city, 16 jobs were lost with a business that left the city.

This makes D.C. a larger exporter than the rest of the Washington metropolitan area.2 In fact, the rest of the metropolitan area comes close to breaking even. In the same period, for every 1 business that moved to the rest of the Washington metropolitan area, 1.03 moved out.3 And, the rest of the Washington metropolitan area is a net importer of jobs: for every 10 jobs that were lost with a business that left the rest of the Washington metro area, 11.3 jobs were gained with another business that relocated to the rest of the Washington metropolitan area.

#2. Historical trends show that D.C. has been relatively strong in attracting establishments coming from outside the region. But, D.C. tends to lose establishments to other jurisdictions within the region.

Between 1990 and the early 2000s, though still a net exporter of businesses, D.C.’s ability to attract new businesses improved. This growth, however, started to stagnate in the mid-2000s and in recent years, progress has begun to reverse – particularly when it comes to inter-regional business migration trends.

Since the mid-1990s D.C. has been relatively strong in attracting establishments coming from outside the region. However, in recent years, the region’s core4, has been rapidly improving in this area, indicating increasingly competitiveness within the region.

#3. Most establishment moves occur within the region.

Between 1990 and 2019, 80 percent of establishments that left D.C. moved to somewhere else in the Washington metropolitan area.5 And, 67 percent of establishments that moved to D.C. came from somewhere else in the metropolitan area.6 This indicates D.C.’s greatest competitors are its neighbors.

Moves from D.C. to elsewhere in the region are less disruptive to the city’s economy than moves to somewhere outside the region. While D.C. may lose a business, that business’s workers may still choose to live in D.C. And, that business may attract complimentary businesses that have the choice to locate in D.C.

Still, while the Washington metropolitan area shares a labor force and many economic strengths, D.C. has, on net, lost businesses to elsewhere in the region. This can be an indicator of what businesses are lacking in D.C. and feel that they can get elsewhere.

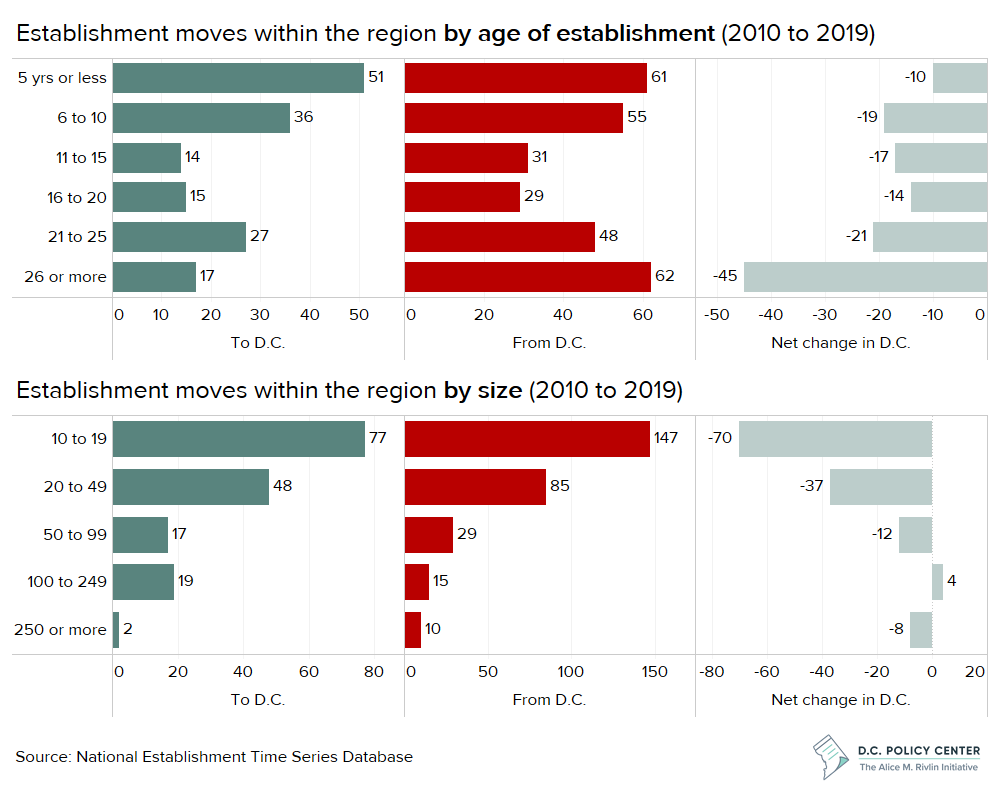

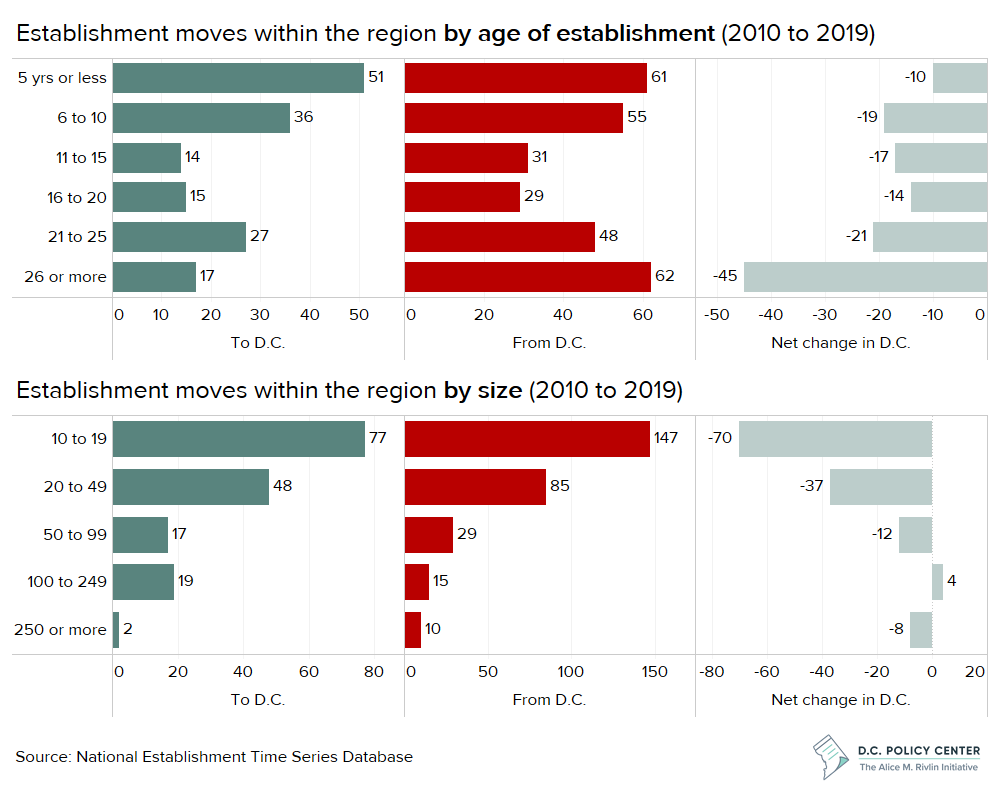

#4. D.C. is best at attracting small and young firms—but even still, the city is a net exporter of these firms to elsewhere in the region.

A count of establishments that leave D.C. for elsewhere in the region by firm age forms a bell curve, meaning D.C.’s greatest losses tend to be on opposite ends of the spectrum. Between 2010 and 2019, of the firms that left D.C. for elsewhere in the region, 61 (or 21 percent) had been around for 5 years or less and 62 (or 22 percent) had been around for 26 years or more.

However, nearly a third of all establishments that relocated to D.C. from elsewhere in the region were young (5 years or less). As a result, while D.C. has a net loss across all establishment age groups, these losses are concentrated in older firms.

By size, between 2010 and 2019, over half of the firms that left D.C. for elsewhere in the region were small (less than 20 employees). But, similarly, nearly half of the firms that moved to D.C. from elsewhere in the region were also small. Still, D.C. is a net exporter of small businesses. This could be explained, in part, by the fact that small businesses seem to move more often: About half of all inter-regional moves between 2010 and 2019 stemmed from firms with less than 20 employees.7

In general, D.C. is strongest in attracting small and young businesses from elsewhere in the region. But D.C. is also an exporter of firms that fit this description. Small, young businesses can more readily move because they don’t have a long history with clients, customers, or workers in any jurisdiction. And they may need to operate in different environments as they begin to mature. Older, well-established businesses that leave D.C., however, could be growing out of the city, though there are many reasons a firm may choose to relocate.

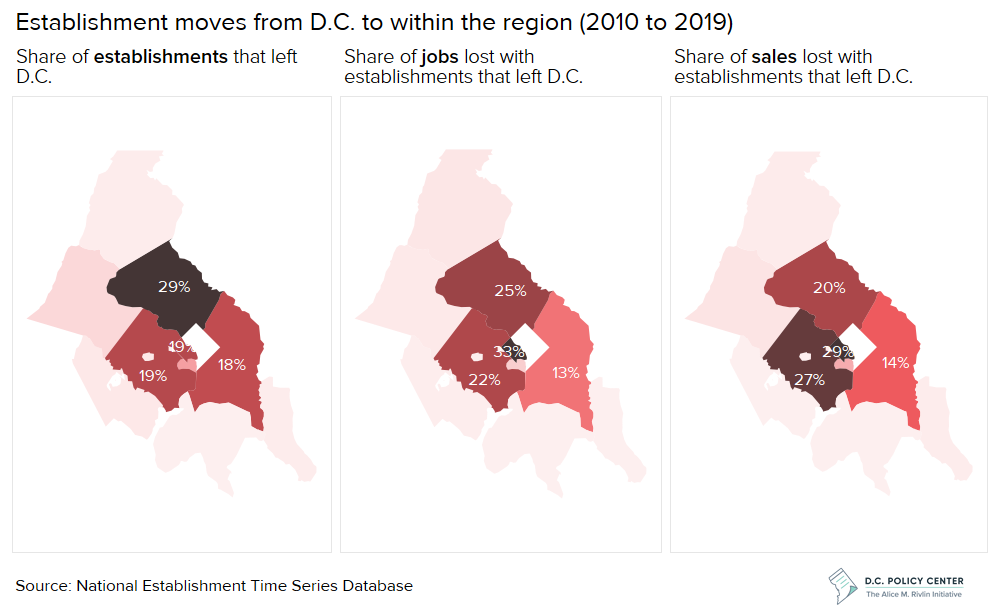

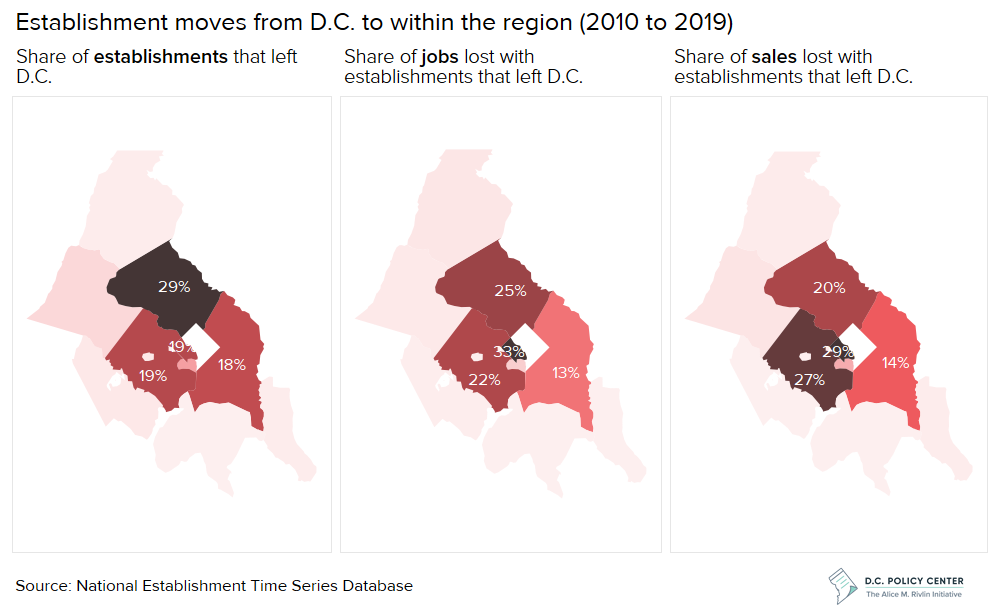

#5. Nearly a third of establishments that leave D.C. for another jurisdiction within the region move to Montgomery County. However, Northern Virginia jurisdictions attract more large, high-sales establishments leaving D.C.

Between 2010 and 2019, most establishments that left D.C. for another jurisdiction within the region stayed within the region’s core, and 29 percent of these establishments left D.C. for Montgomery County.

However, 33 percent of jobs lost with establishments that left D.C. for another jurisdiction within the region went to Arlington, and the bulk of sales lost with establishments that left D.C. for another jurisdiction within the region went to Arlington (29%) and Fairfax County (27%). This implies that Northern Virginia counties are attracting the larger and high-revenue companies looking to move out of D.C.

Note on data

The National Establishment Time Series (NETS) Database is a private sector source of U.S. business microdata from Walls & Associates. The data is self-reported by employers. As such, this data will not likely match other data sources that track establishments.

Excluded from our calculations are any firms that were labeled as having moved often (more than once between 1990 and 2019) and very small firms (less than 10 employees) to improve data accuracy.

Endnotes

- This calculation only includes net moves (excludes moves that occurred within D.C.). Between 1990 and 2019, 1,482 firms moved to D.C. and 2,479 firms moved out of D.C. As a point of comparison, 5,358 moves occurred within D.C. in this time.

- The rest of the metropolitan area refers to the Washington metropolitan area excluding D.C.

- This calculation only includes net moves (excludes moves that occurred within the rest of Washington metropolitan area). Between 1990 and 2019, 13,801 firms moved to the rest of the Washington metropolitan area and 13,396 firms moved out of the rest of the Washington metropolitan area. As a point of comparison, 14,489 firms moved within the rest of the Washington metropolitan area.

- The region’s core includes counties in the Washington metropolitan area that are accessible by WMATA Metrorail, excluding D.C.: Arlington, Loudoun, and Fairfax counties in Virginia, Montgomery and Prince George’s counties in Maryland, and Alexandria city in Virginia.

- This calculation excludes firms that moved within D.C. Between 1990 and 2019, 1,990 firms moved from D.C. to elsewhere in the region and 489 firms moved from D.C.

- This calculation excludes firms that moved within D.C. Between 1990 and 2019, 988 firms moved from elsewhere in the region to D.C. and 494 firms moved from elsewhere in the country to D.C.

- This calculation excludes firms that moved within their existing jurisdictions. Between 2010 and 2019, there were 1,830 moves within the Washington metropolitan area (excluding inter-jurisdictional moves) and 931 of these moves were firms with less than 20 employees. If you include inter-jurisdictional moves in the region, 49 percent of movers had less than 20 employees (2,285 out of 4,696 total moves).