In D.C., many adults lack a high school diploma, and most jobs require some postsecondary education. Thus, career and education support for adult learners is incredibly important. While workforce training and postsecondary learning programs are common, D.C. is rare in that it has publicly funded schools at which adult learners can earn a high school degree, gain English language skills, or enroll in workforce programs.

This report takes stock of adult learners at adult public charter schools in D.C., program offerings and outcomes, connections to employment, and supports for learners, including during the pandemic.

Quick links

- Access a printer-friendly PDF version of the full report here.

- Report highlights & summary / En español

- Information on the in-person launch event here.

Introduction

Career and education support for adult learners1 is critical in D.C., where 7 percent of adults over the age of 25 (about 34,500) lack a high school diploma2 and an estimated 22 percent of adults ages 16-74 are reading at or below a very basic level.3

While workforce training and postsecondary learning programs are common, it is rare to see publicly funded schools at which adult learners can earn a high school degree or gain other skills. D.C. stands out on this front: according to national enrollment data, D.C. is home to 47 percent of adult learners who attend publicly funded schools.4

What is an adult public charter school?

For the purposes of this report, an adult public charter school is one of the nine identified schools in D.C. that primarily serve adults outside of a high school setting. The schools have a diverse set of offerings tailored to the needs of the population of learners that they serve. Some schools are focused on English language services and so offer English classes at a variety of levels. Other schools may be focused on supporting those who do not have a high school diploma, helping them to earn an equivalent degree such as a GED.

Schools may also offer workforce development programs that take learners through a set program to earn an industry-recognized credential. Many of D.C.’s nine adult public charter schools offer some combination of these offerings.

In addition to academic and workforce offerings, all adult public charter schools also offer robust student services to help support learners persist in their education. Schools may connect learners to public benefits resources related to food, housing, childcare, or transportation. Most schools also offer personalized career or postsecondary counseling.

Unlike District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) Opportunity Academies, which are more focused on serving younger students, adult public charter schools tend to serve populations above the age of 25. Also, unlike learners at Opportunity Academies and learners at Goodwill Excel PCS, learners at adult public charter schools also tend to enter with the goal of achieving better employment rather than with the goal of earning their high school diploma or taking high school-level courses. This report highlights both DCPS Opportunity Academies and Goodwill Excel PCS, in addition to other workforce programs, throughout the report to show D.C.’s robust landscape of offerings for adult learners.

In 1995, Congress passed the School Reform Act, which established public charter schools in D.C., including those serving adult learners.5 At present, there are nine public charter schools in the District serving adult learners. At these public charter schools, adult learners seek credentials, certificates, or General Education Diploma (GED)/National External Diploma Program (NEDP) completion, and develop skills needed to attain or improve employment or pursue additional education.

As public schools, adult public charter schools receive public funding on a per pupil basis through D.C.’s funding formula. In school year 2023-24, adult public charter schools will receive $11,872 for each adult learner and $19,830 for each alternative student. Most schools serve students in both groups.6 These payments tend to be higher than federal funding for adult learners, or what states and localities typically spend on workforce training or GED programs.

Educational attainment and training can translate to a large difference in income and job opportunities. On average, D.C. residents who do not have a high school diploma earn $5,000 less annually than those with a high school diploma as their highest level of education.7 In addition to access to high-paying jobs, a high school diploma or equivalent also makes it possible to pursue an associate or bachelor’s degree. Obtaining these degrees is associated with earnings that are $11,000 and $46,000 higher, respectively, than earnings associated with only a high school diploma.8

Based on interviews with adult public charter school leaders, the 5,144 adults who are enrolled in the District’s adult public charter schools enter with a variety of goals, ranging from improving career and economic outcomes to being able to better communicate with their children’s teachers. For example, some adult learners may have found it difficult to be successful in traditional high schools, and others may have completed high school but did not achieve a level of literacy necessary to enter a workforce program. Adult public charter schools also serve immigrants who may not have had a chance to complete formal education in their country of birth or who may have finished formal education in a different country but now need to learn English.

Adult public charter schools respond to this diverse set of needs through academic and workforce supports, in addition to connecting learners to external resources such as connections to employers, postsecondary institutions, and social service programs.

While the presence of adult public charter schools in D.C. is common knowledge, there is no comprehensive, systems-level information about their learners and how these schools differ from other workforce training programs for use by policymakers, employers, and the D.C. community. This report takes stock of adult learners at adult public charter schools in D.C., program offerings and outcomes, connections to employment, and supports for learners, including during the pandemic.

Notes on methodology

The findings presented in this report rely on qualitative and quantitative analyses.

- Data analyses: The report presents an analysis of the metrics reported for adult public charter schools by the DC Public Charter School Board (DC PCSB) in School Quality Reports and the Performance Management Framework (PMF). It also presents state-level data for programs participating in the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). This report also utilizes additional PMF data provided by DC PCSB and data on age ranges of adult learners provided by OSSE in response to data requests from the D.C. Policy Center.

- Program review: The program offerings section relies on reviews of PMF reports and the websites of all nine adult public charter schools.

- Interviews: We also completed a series of seven semi-structured qualitative interviews with school leaders from adult public charter schools about program goals and outcomes, supports for learners, barriers for learners, impact of COVID-19, evaluation methods, and general reflections on challenges and bright spots. The report presents summary information from these interviews by coding for common themes.

The nine adult public charter schools examined in this report were chosen because they are all identified as adult public charter schools by DC PCSB and as such have specific reporting requirements. DCPS Opportunity Academies and Goodwill Excel PCS are sometimes also categorized as adult-serving schools but were not included in the report’s analysis. Both are highlighted separately in the report.

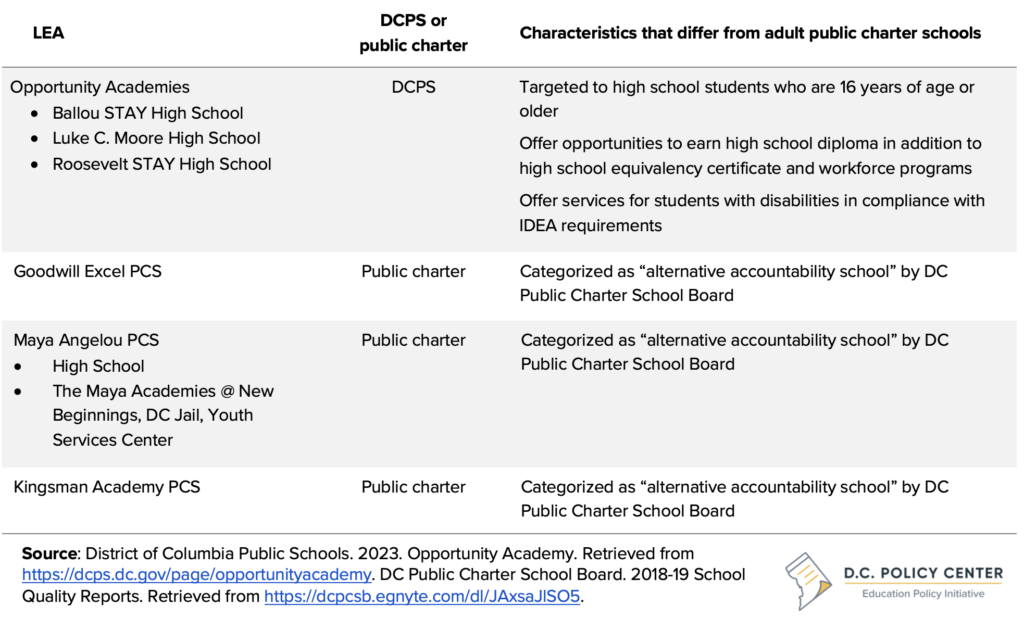

Adult public charter schools and their learners

In school year 2022-23, there were 6,949 learners enrolled as adult or alternative learners in D.C. Of these learners, 5,144 attended one of the nine adult public schools that are the focus of this analysis (74 percent of all adult or alternative learners). The remaining 26 percent of adult and alternative learners attend DCPS Opportunity Academies and alternative public charter high schools that focus more on high school-age and young adult students (See Table 2 in Appendix for information on other adult-serving public schools and Table 3 for characteristics of each adult public charter school).

Adult public charter school learners represented 5 percent of all enrollment at DCPS and public charter schools in school year 2022-23.

DCPS Opportunity Academies

DCPS offers three Opportunity Academies (Ballou STAY High School, Luke C. Moore High School, and Roosevelt STAY High School) that serve young adults aged 16 to 22 years old seeking to earn their high school diplomas, participate in career and technical education, and prepare for postsecondary success.[1] At Roosevelt STAY and Ballou STAY, older adults over the age of 22 may earn their NEDP and participate in CTE programs.

Additionally, all three schools are equipped to serve students with disabilities who have specific learning requirements as well as students who are English learners. They also have students who take the PARCC statewide assessment. While adult public charter schools also serve learners in alternative settings and with learning differences, they do not have the same type of supports (including IDEA funding) or compliance requirements (including Individualized Education Plans, or IEPs) which more closely mirror traditional PK-12 offerings.

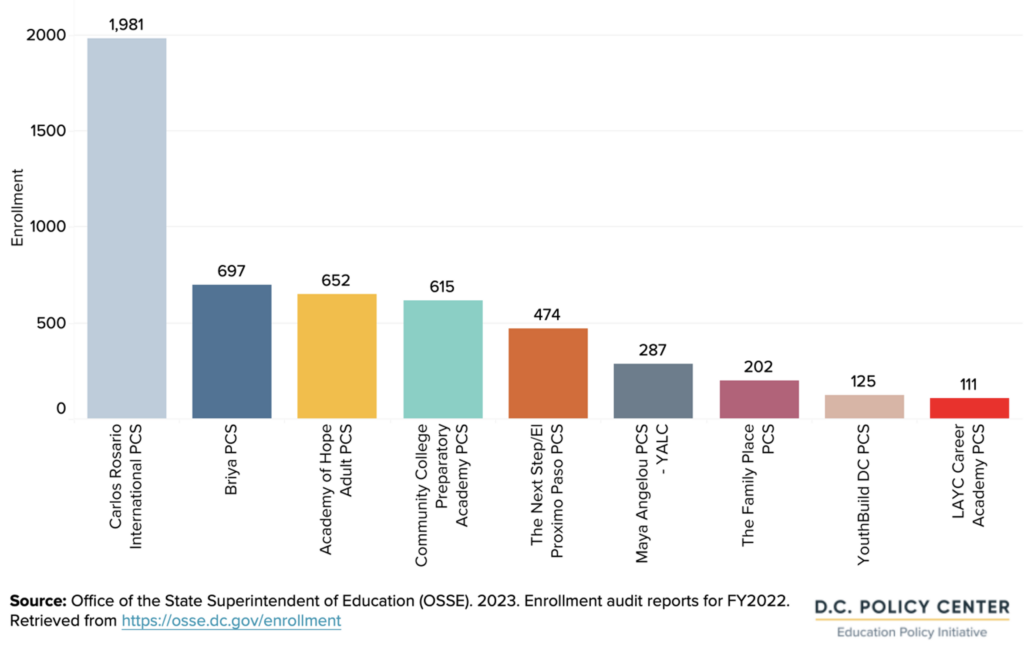

Adult public charter schools vary greatly in size.

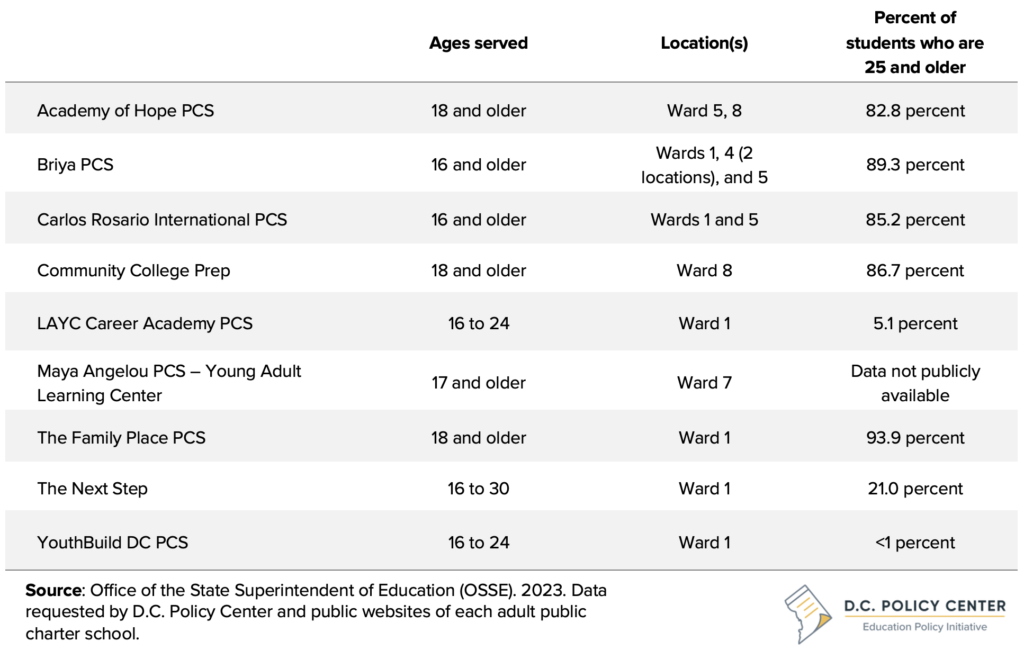

The adult public charter schools vary widely in size, with the largest school, Carlos Rosario International PCS, enrolling 1,981 learners (39 percent of all students attending these nine schools). The smallest three schools are The Family Place PCS, YouthBuildDC PCS, and LAYC Career Academy PCS, which have an average school size of 146.

Figure 1. Enrollment in adult public charter schools, school year 2022-23

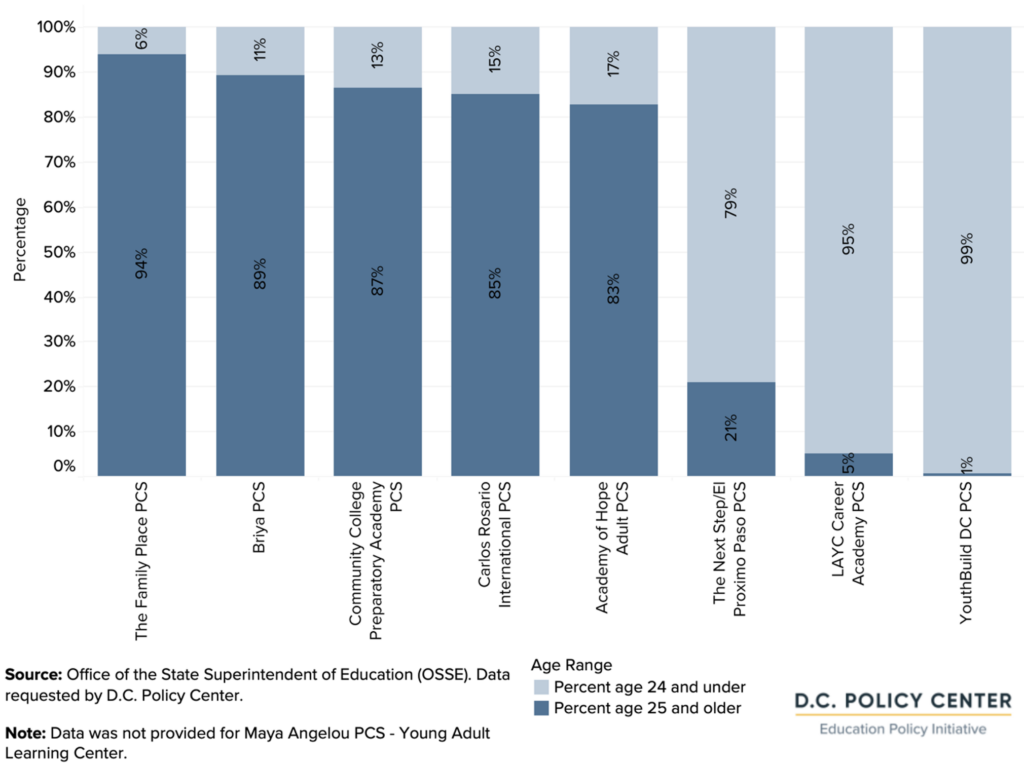

Six of the adult public charter schools serve adult learners of all ages.

Six of the schools serve all adult learners, with no upward age limit. (The lowest allowed entry age is 16.)9 At five of these six schools, students who are 25 or older make up at least 80 percent of the school’s total enrollment.10 Four schools target young adult learners (see Table 3 in Appendix). These schools would offer admission to students who are at least 16, and not older than 30 (and for two of these schools, the cutoff age is 24).

Figure 2. Share of learners enrolled at adult public charter schools, by age range and school

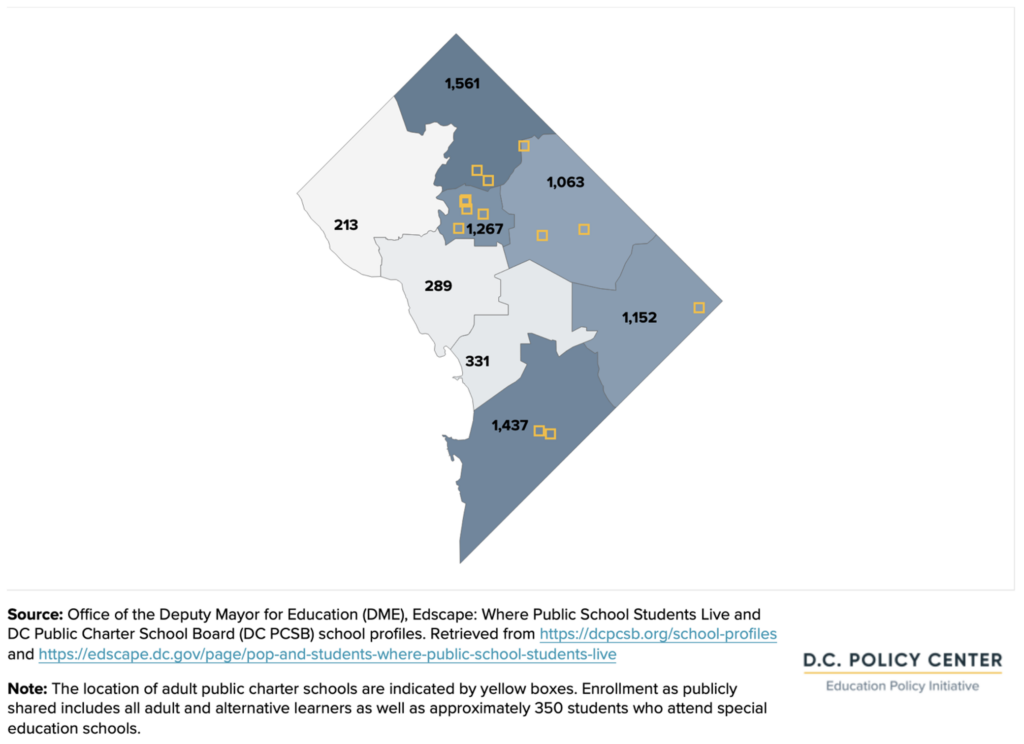

Adult learners live in every ward, but they are concentrated in Wards 4 and 8.

Publicly available data on adult learners attending adult public charter schools by ward also include the other 24 percent of adult and alternative learners as well as approximately 350 students attending special education schools. Based on this information, Wards 4 and 8 are likely to have the highest numbers of adult learners. Wards 1, 5, and 7 also have high numbers of residents who are likely to be adult learners.

Six of the nine adult public charter schools have locations in Ward 1. There are eight additional locations in Wards 4, 5, 7, and 8. (Some schools have more than one location.)

Figure 3. Adult, alternative, and special education school enrollment by ward, and adult public charter school locations, school year 2022-23

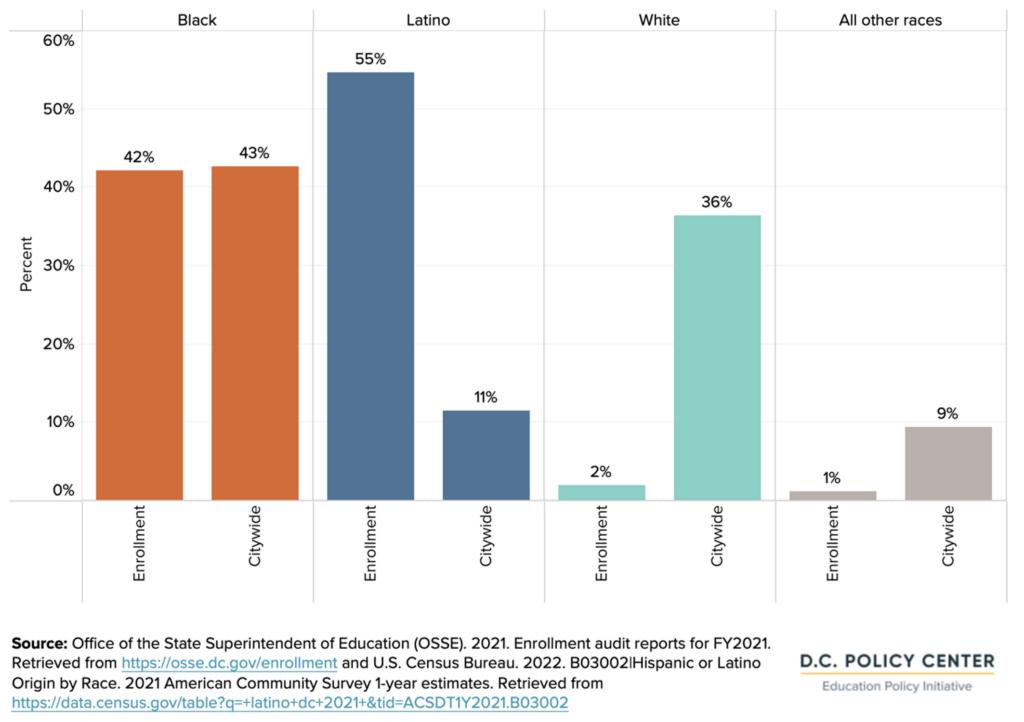

Adult learners tend to be Black or Latino.

Across all adult public charter schools, 55 percent of learners are Latino, and 42 percent are Black. Very few learners at adult public charter schools are white or other races or ethnicities.

This composition looks very different from the racial and ethnic composition of D.C.’s population, or the composition of students enrolled at PK3 through grade 12. For example, only 11 percent of D.C.’s population is Latino, and only 17 percent of students enrolled in PK3 through grade 12 are Latino.11 The share of Black learners in adult public charter schools is identical to the D.C.’s Black population share, but less than the share of Black students enrolled in lower grades (65 percent).12

At the school level, however, enrollment is even more ethnically concentrated. All but one adult public charter school tend to serve either a majority of learners (more than 70 percent) who are Latino or a majority of learners who are Black, with only one school (LAYC Career Academy PCS) serving about half Latino and half Black learners. Demographics of the learners vary by location: Schools in Wards 1 and 4 tend to serve a higher share of Latino learners, while schools in Wards 7 and 8 tend to serve higher shares of Black learners.

Figure 4. Enrollment by race at adult public charter schools compared to citywide demographics, school year 2021-22

A majority of learners at adult public charter schools speak a language other than English at home.

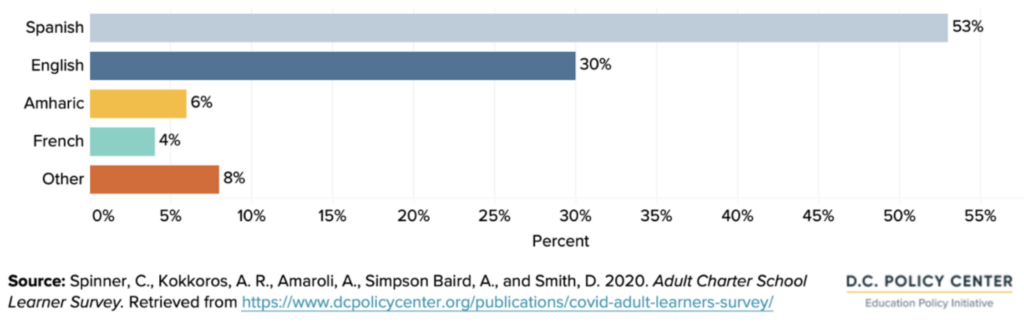

A survey of adult learners conducted in May 2020 found that approximately 70 percent of respondents speak a language other than English at home: 53 percent of respondents speak Spanish at home, 6 percent speak Amharic, 4 percent speak French, and 8 percent speak other languages. Specifically focusing on this population, six adult public charter schools offer English language programs.

Figure 5. Languages spoken at home by adult public charter school students

Program offerings and outcomes at adult public charter schools

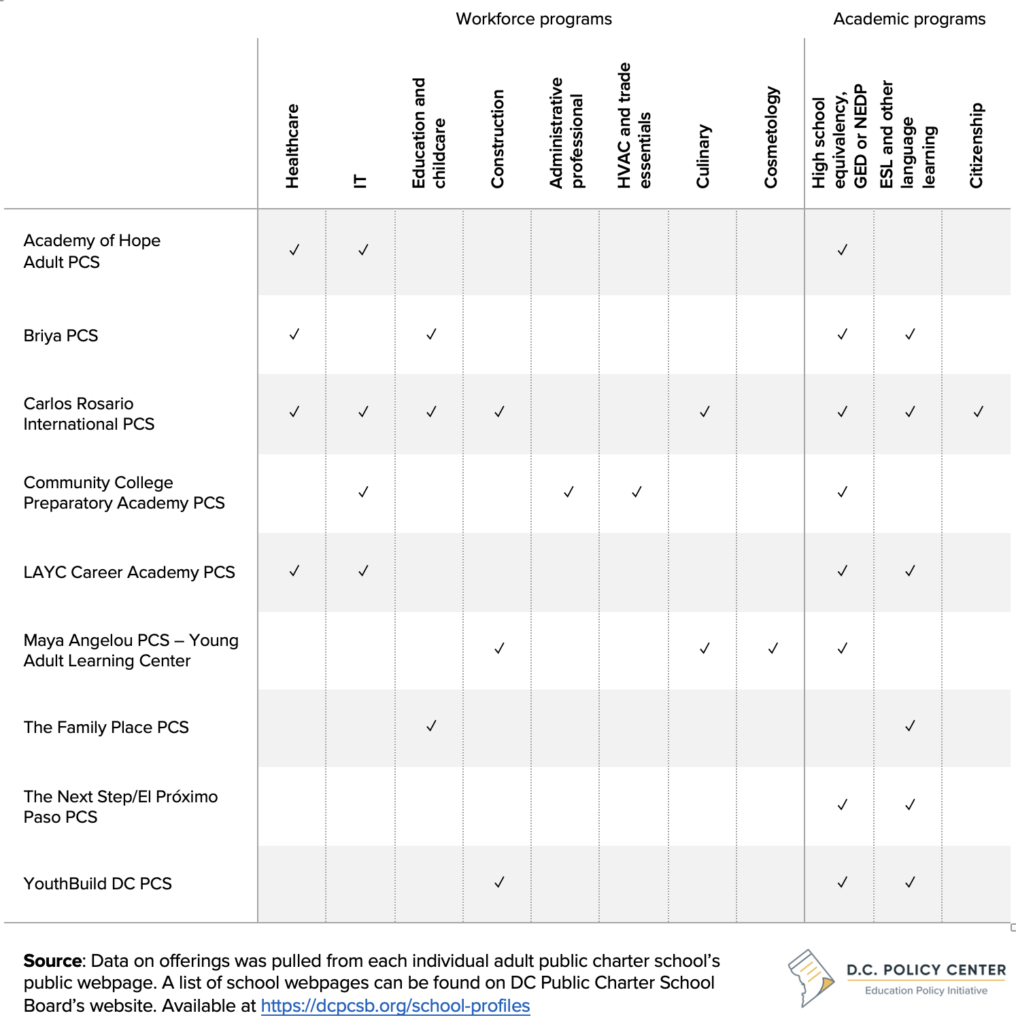

Adult public charter schools engage learners on their goals and design responsive academic and workforce opportunities. This section summarizes how adult public charter schools identify learners’ goals, the academic and workforce programs that they offer to meet these goals, and the available outcome metrics. (See Table 1 in Appendix for a matrix of program areas offered.)

Employment is the most common motivation for adult learners.

In interviews, school leaders reported that the most common goal for adult learners when entering their schools is to get a job, or to get a better job. A better job could be one with higher pay, a more reliable or more convenient schedule, one that allows learners to only work one job instead of multiple, or one with better opportunities for growth.

While most learners are looking for greater economic stability, they travel different paths. Many learners aim to learn or improve their English language skills to get a better job. Many learners also aim to obtain high school degrees or other credentials to improve their job prospects or pursue a postsecondary degree.

School leaders also report that learners who are parents identify improving outcomes for and supporting their own children as a goal. This goal is most commonly identified at adult charter schools that serve immigrants. Learners want to improve their English skills to support their children’s schoolwork, and critically, to better communicate with their children’s teachers and schools.

Adult public charter schools respond to the goals of learners by customizing the type, frequency, and format of program offerings. Additionally, each adult public charter school tends to serve a specific population of adult learners, and their offerings reflect the needs of their unique student body.

School leaders also want to ensure that their program offerings align with learners’ interests. Most schools have avenues to incorporate learner input into decision-making and governance of the school, for example, through student councils or advisory groups. Most schools also seek input through learner surveys and regularly scheduled townhall meetings.

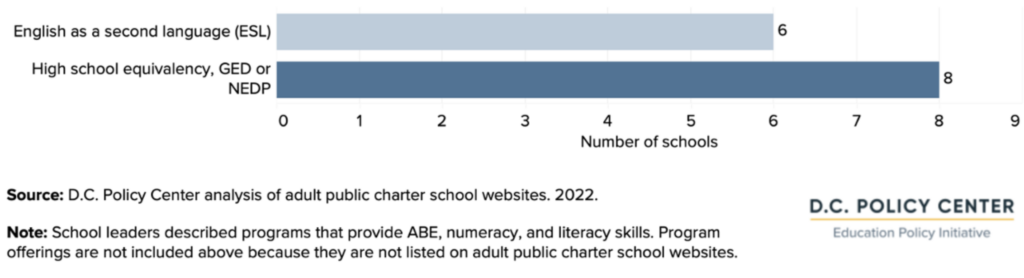

Adult public charter schools typically offer both academic supports and workforce development programs.

Eight of the nine adult public charter schools covered in this report offer courses and programs in both areas.13 Academic programs at adult public charter schools include high school equivalency programs, literacy and numeracy instruction, and English as a Second Language (ESL) programs.14 All nine adult public charter schools also offer workforce development programs in a variety of in-demand fields. The most common areas are healthcare, IT, early childcare and education, and construction. For most workforce programs, learners can earn an industry-recognized credential or certificate when they successfully complete their coursework.

In addition to describing programmatic offerings, this section also looks outcomes data for learners and displays the median results for adult public charter schools as an indicator for the sector. This section includes data from school year 2018-19, the last year that PMF data are available for all adult public charter schools, and data from school year 2021-22, received from DC PCSB in response to a D.C. Policy Center request.

Academic supports

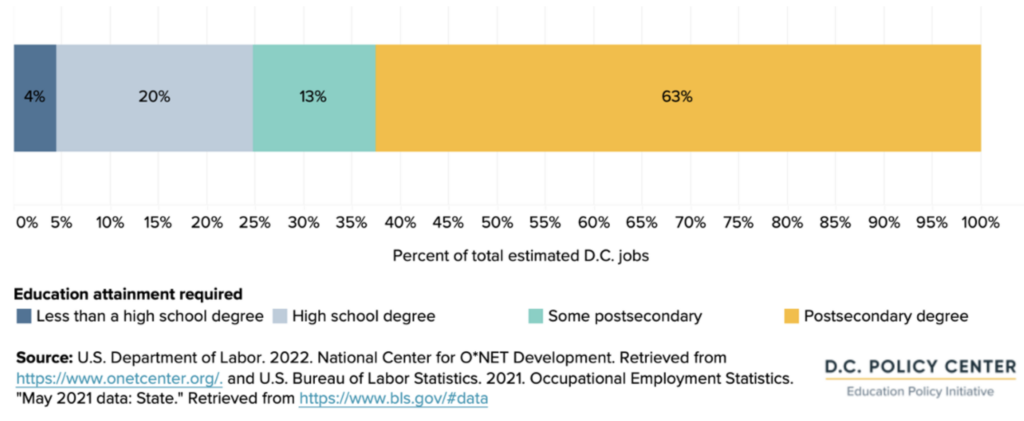

The most common academic program that adult public charter schools offer is high-school equivalency certificates. This is an important support, given that 7 percent of D.C. residents ages 25 and over do not have a high school diploma,15 and 25 percent of D.C.’s public school students do not graduate from high school.16 This presents a mismatch with employment opportunities in D.C. In February 2023, there were approximately 773,000 jobs in D.C., which includes jobs held by individuals commuting into the District from nearby jurisdictions.17 Over half of all District jobs (63 percent) typically require a postsecondary degree. Just 4 percent (an estimated 29,000) of jobs in the District of Columbia do not require a high school education. The remaining 33 percent require a mix of high school and postsecondary credentials.18

Figure 6. Jobs in D.C. by educational attainment, May 2021

High school equivalency support

Eight of the nine schools offer some support to learners who did not earn a traditional high school diploma. At these schools, learners receive supports and take courses as they pursue their GED or NEDP.19 Schools vary in the types of supports they offer for learners taking the GED and NEDP assessments, from holding prep sessions to assigning formal advisors to each student or setting learners up with independent study options.

Figure 7. Academic program offerings in D.C.’s adult public charter schools, school year 2022-23

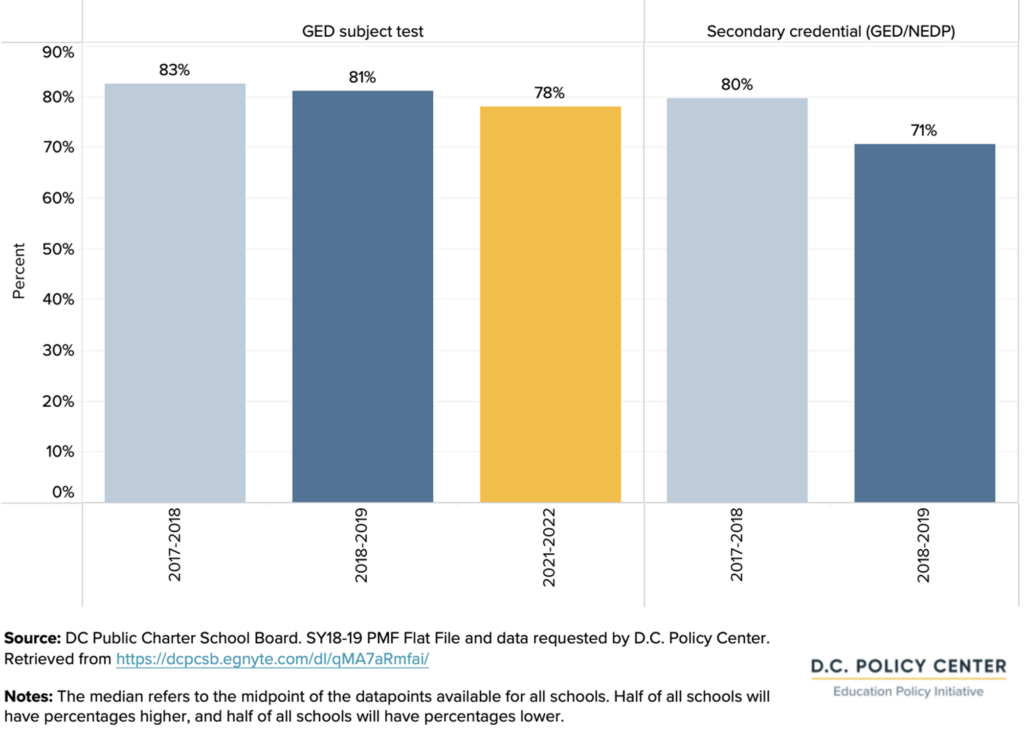

In school year 2018-19, 220 learners attempted a secondary degree. At more than half of the adult public charter schools, 71 percent of learners who attempted a secondary credential earned one; lower than in 2017-18, when 80 percent of those tried earned a credential.20

In school year 2021-22, at more than half of the adult public charter schools, 78 percent of learners who attempted a GED subject test achieved a passing score, which is lower than in school year 2017-18 and school year 2018-19, when 83 percent and 81 percent of learners achieved a passing score, respectively.21

Figure 8. Share of learners at median adult public charter school who attempted and passed a GED or secondary credential test

Goodwill Excel Center PCS

Goodwill Excel Center (GEC) PCS is an adult public charter high school that offers programs on two education sites in D.C. Based on a national model that has schools across five states[1], GEC offers five 8-week terms per year for learners to work toward earning their high school diploma. GEC is different from other adult public charter schools because learners attend classes in all high school content areas as they pursue their diploma. In programs supporting GED or NEDP attainment, classes are more centered around preparing to pass the required tests. GEC is like other adult public charter schools in offering student services such as on-site childcare and transportation assistance. Additionally, GEC also offers several career training classes in hospitality and technology, where learners can earn a professional credential.

“We often hear the desire to reinvent high school and [GEC] came up with a way to reimagine the high school experience for adults. We iterate each year with lessons learned by being entrepreneurial and innovative and constantly responding to the needs of our learners. Because we ground our decisions, programming, and support structures around the relevant needs of our students, we’re more likely to be successful.”

Dr. Chelsea Kirk, Executive Director, Goodwill Excel Center PCS

Literacy and numeracy instruction

In conjunction with GED- and NEDP-focused programs, adult public charter schools also offer literacy and numeracy instruction to learners as described by school leaders. Some workforce development and occupational skills training programs require that applicants can pass an assessment test with at least an 8th grade proficiency level in math and reading.22 Thus, this type of instruction can provide an additional bridge to workforce development programs. School leaders emphasized that instruction in math and reading is contextualized in workforce-specific examples to be relevant for learners. For example, learners who are interested in a medical career path may engage in math instruction by calculating prescription dosages, or they may have literacy lessons involving medical-specific texts.

Adult Basic Education (ABE) tests are used to measure basic skills that adults need to succeed in subjects such as reading, math, and language.2324 The ABE tests measure progress through educational functional levels as learners move through different levels of literacy. In school year 2021-22, eight schools enrolled 1,191 learners in ABE programs, which may be held in conjunction with GED or NEDP programs. This is a decline from school year 2018-19 when the same eight schools enrolled 1,667 learners in these programs.

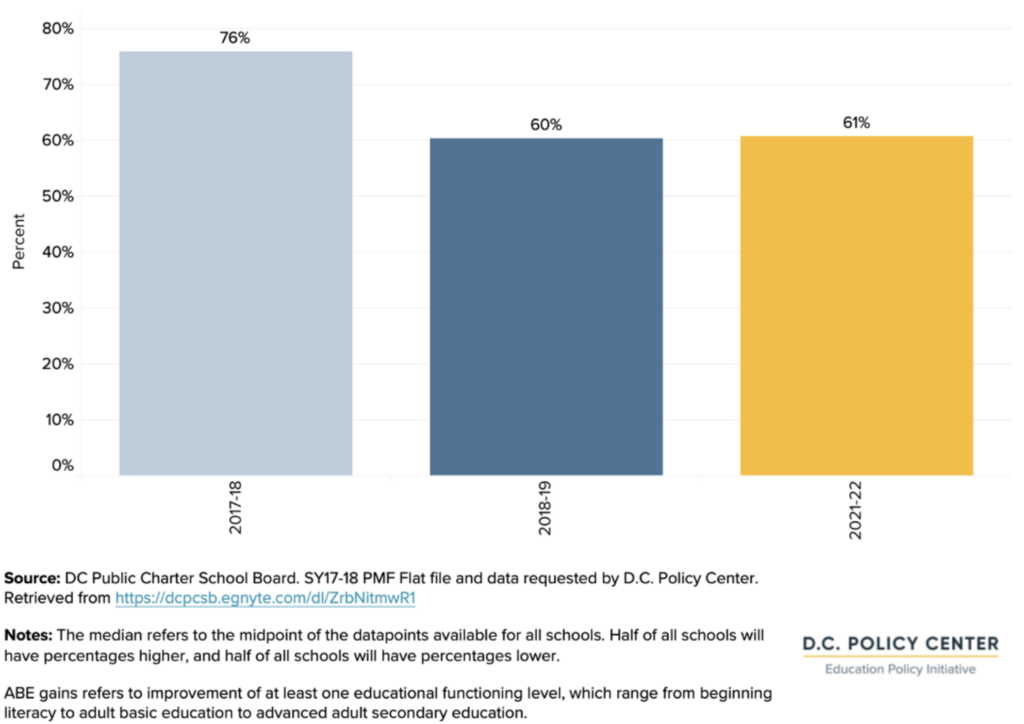

Out of those who enrolled and participated in testing, at more than half of the adult public charter schools, 61 percent made gains at a school in school year 2021-22, almost no change from the 60 percent who made gains in school year 2018-19. Making ABE gains means improvement by at least one educational functioning level, which range from beginning literacy to adult basic education to advanced adult secondary education.

Figure 9. Percent of learners at the median adult public charter school who made gains in basic skills (measured by ABE)

English language instruction

The next most common support is English instruction through ESL programs. These programs provide English classes to adult learners at multiple levels of difficulty. Five adult public charter schools in D.C. operate ESL programs. These schools have a large focus on reaching learners who speak a language other than English, and structure opportunities to serve learning purposes, whether those be professional, or more personal like communication with their child’s teacher.

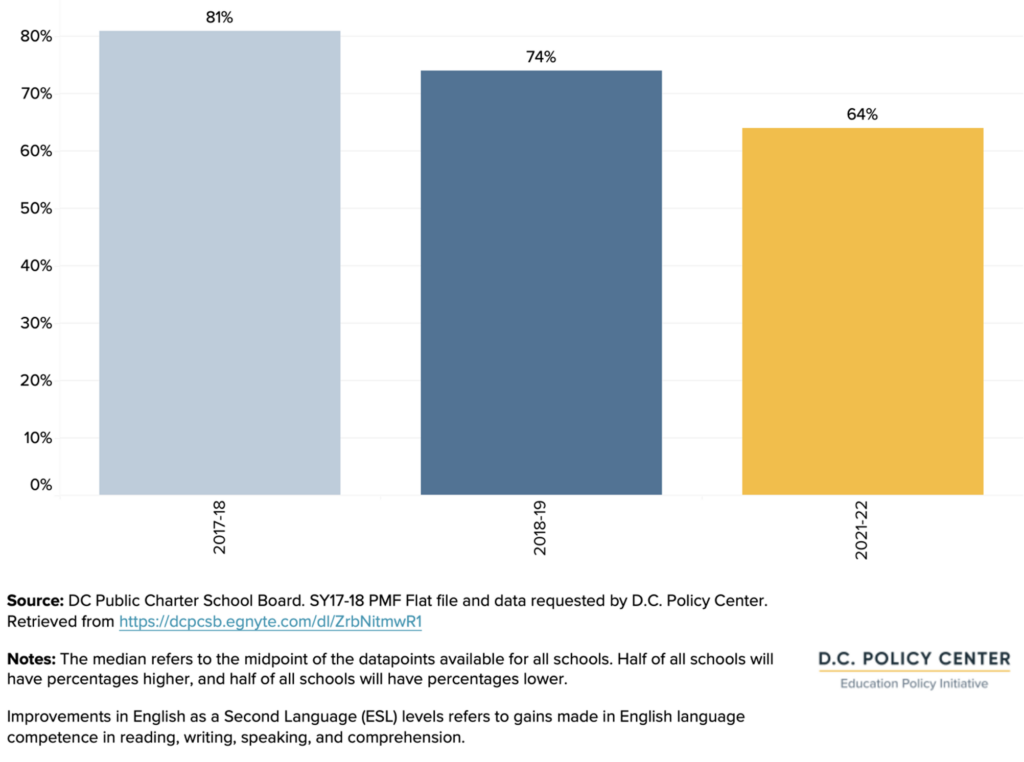

Six of the nine adult public charter schools reported the number of learners enrolled in their ESL classes. In school year 2021-22, these schools collectively enrolled 1,738 learners in ESL classes, a decline from school year 2018-19 when 2,177 learners were enrolled. Of the learners who completed the related ESL tests,25 at more than half of the adult public charter schools, 64 percent of learners made gains in their English language competence in reading, writing, speaking, and comprehension that moved them from one level of ESL to another. This is a decline from pre-pandemic in school year 2018-19, when 74 percent of learners made such gains.

Figure 10. Percent of learners at the median adult public charter school who made gains of at least one ESL level

Postsecondary partnerships

Most adult public charter schools also offer supports for postsecondary services. These supports can include opportunities to meet with an advisor to receive guidance about postsecondary decisions or can be a more formal series of sessions focused on financial aid, admissions, test preparation, and college visits. According to interviews with school leaders, supports are usually offered to learners throughout their school experience as they begin planning their next steps.

Several schools also partner with local universities to provide opportunities for learners if they choose to enroll in postsecondary education after completing their term.

- At Briya PCS, learners who complete the Allied Health Program and then enroll at Trinity Washington University can transfer seven articulated college credits that will count toward a secondary degree. Briya PCS also has a partnership with the University of the District of Columbia (UDC) to transition learners into a bilingual associate’s degree in early childhood after earning their Child Development Associate (CDA) Credential at Briya PCS.

- Academy of Hope Adult PCS has an articulation agreement with UDC where learners can receive up to four articulated college credits for classes in their internet computing and college prep and success pathways.26 Learners at Academy of Hope PCS can also participate in dual enrollment opportunities at postsecondary institutions in D.C. Several learners are currently dual enrolled at Catholic University.27

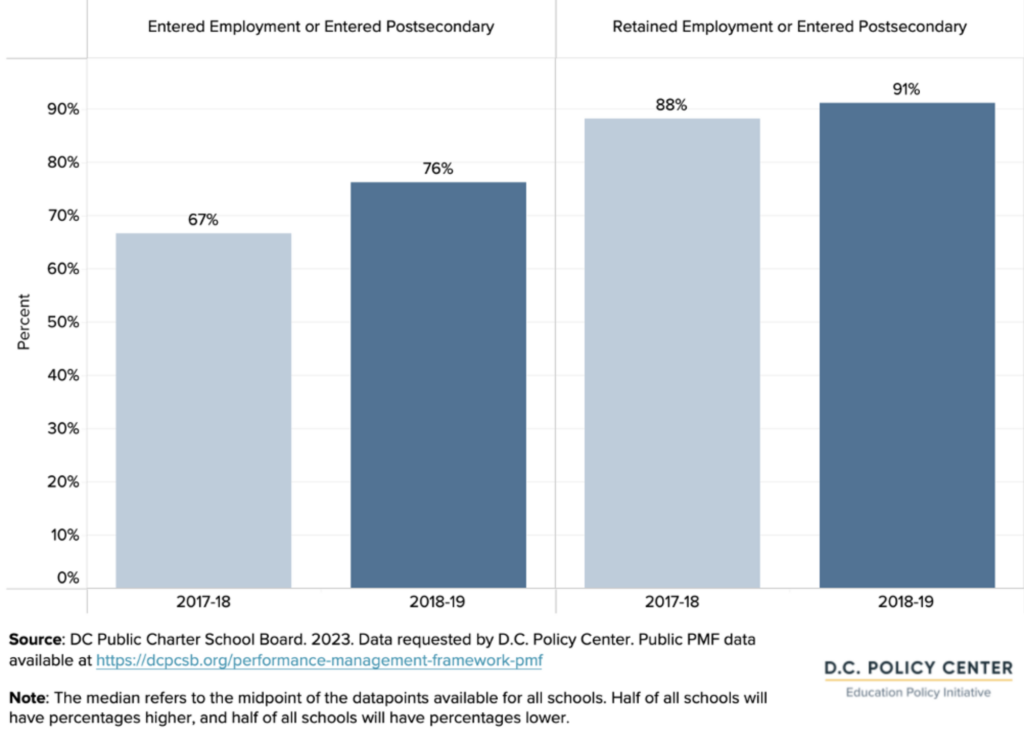

Of learners exiting programs at adult public charter schools, 76 percent newly entered employment or postsecondary, and 88 percent retained employment or entered postsecondary enrollment in school year 2018-19. Data for most schools are not available for school year 2021-22.

Figure 11. Percent of learners at the median adult public charter school who entered or retained employment or entered postsecondary

Workforce supports

All nine adult public charter schools seek to educate learners in a variety of workforce programs. In many programs, learners have the potential to work toward earning an industry-recognized credential. This section describes the workforce development programs and opportunities to earn credentials that are offered at adult public charter schools in D.C., and are part of the larger picture of workforce training programs in D.C.

Workforce training programs in D.C.

In fiscal year 2021, D.C. spent $100.5 million on workforce development and adult education,28 of which at least $1.2 million went to adult public charter schools, supplementing the $89.1 million in per-pupil funding that they receive.

D.C.’s spending on workforce and adult education reached 50,607 participants with 37,197 completers,29 making adult public charter schools part of a larger set of opportunities for adults to gain additional skills and knowledge in D.C. But adult public charter schools stand out in three ways from other workforce programs in D.C.: In particular, they offer academic programs and support their learners with more holistic supports over a longer period of time than other workforce training programs in D.C.

Workforce training programs in D.C. target at least five different groups of learners: adult learners (ages 18 and up), youth (typically ages 18 to 24), people with disabilities, justice-involved persons, and older adults (targeted to age 50 and up). There are a few approaches to reach these groups through education, skills training, work readiness and job search assistance, and on-the-job training. A distinctive characteristic of adult public charter schools is their focus on academic growth for adult learners, alongside job training and workforce readiness.

Nested within these programs, the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) is a federal program that provides grant funding to states to encourage the development of workforce programs. To be eligible, providers must offer both adult education and literacy activities, as well as targeted workforce preparation and training. Out of the list of 12 grantees, five are adult public charter schools: Academy of Hope PCS, Briya PCS, LAYC Career Academy PCS, The Family Place PCS, and YouthBuild DC PCS.30 The other seven include government agencies, community-based organizations and nonprofits, and workforce development organizations.31 WIOA Title II Adult Education Program served 1,093 participants in D.C. across all of its programs from July 2021 to June 2022.32

Other common opportunities for adults in D.C. to advance their skills and knowledge include job skills training offered by private training providers, nonprofits, the University of the District of Columbia Community College (UDC-CC); apprenticeships and on-the-job-training through the Department of Employment Services (DOES) and DC Infrastructure Academy (DCIA); or other educational programs at DCPS Opportunity Academies.

Adapted from DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI)’s “Where Do DC Residents Go When They Are Looking For Work?” Retrieved from https://www.dcfpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/DCFPI-Workforce-Primer.pdf

The workforce development programs offered by adult charter schools help adult learners build skills that align with D.C.’s job market. Adult public charter schools typically consider what sectors in D.C. are growing and where job growth can be expected, especially searching for fields that are accessible to those without higher degrees but that have opportunities for growth and earning a living wage in D.C. In interviews, school leaders most commonly identify Information Technology (IT), construction, and healthcare as fields fitting in the niche of these criteria. Construction and healthcare have both been identified nationally among the fastest-growing occupations that pay well and don’t require a college degree.33

Healthcare credentials

Three schools—Academy of Hope PCS, Briya PCS, and Carlos Rosario International PCS—offer credential-granting programs in the healthcare field. Academy of Hope PCS offers a nursing assistant and phlebotomy program; Briya PCS offers a medical assistant program; and Carlos Rosario International PCS provides a nurse aide training program. In most programs, learners participate in hands-on instruction led by a licensed instructor. All programs have partnerships that give learners the opportunity to directly work with patients. All three programs support learners to complete a certification exam for a nationally- or D.C.-recognized credential in the medical field.

Construction credentials

Four schools offer courses in the construction field. Carlos Rosario International PCS, Community College Preparatory Academy, YouthBuild DC PCS, and Maya Angelou PCS-Young Adult Learning Center all offer such programs.

Unlike the medical programs where learners choose a specific career pathway, the construction programs offer learners the opportunity to explore the field through exposure to a variety of different construction-related jobs and information. For example, at Maya Angelou PCS-Young Adult Learning Center’s Home Builder’s Institute, learners rotate between seven different construction trades over the course of the program. In YouthBuild DC PCS’s program, learners spend their time split between construction worksites and vocational classes.

In all programs offered, learners can work toward receiving a trade-recognized certification including OSHA certifications, HVAC-related EPA certifications, or a National Center for Construction Education & Research (NCCER) core certification.

Information technology

Several schools offer programs related to the information technology or IT field. Programs in this area concentrate on connecting learners with entry-level certification opportunities. The CompTIA is a widely recognized certification in the IT field and includes instruction on troubleshooting, cloud computing, security, and help with operating systems. Three adult public charter schools in D.C. offer courses and certifications related to CompTIA. Additionally, Community College Preparatory Academy also offers a Google data analytics professional certificate.

Other credentials

The remaining workforce development programs are offered at one adult public charter school each—learners who want to earn these credentials will likely need to target their application to one of these schools.

- Administration: Community College Preparatory Academy offers a program for administrative professionals including instruction on Microsoft packages.

- Agriculture: Maya Angelou PCS-Young Adult Learning Center offers a Seeds for Success Hoop House program where learners learn about urban forestry and can earn their Serve Safe Food Handlers certificate.

- Early childhood education: Briya PCS offers a childcare pathway where learners work in licensed early education settings while completing the course’s 480-hour practicum. After completion of the program, learners are assessed by the Council for Professional Recognition to receive the national Child Development Associate (CDA).

- Cosmetology: Maya Angelou PCS-Young Adult Learning Center offers two certification programs for lash extension and nail technician certifications.

- Education: Carlos Rosario International PCS offers a 5-month program for advanced English learners to become certified teaching assistants.

- Hospitality: Carlos Rosario International PCS offers a 5-month program that prepares learners for a career in food service.

Connecting adult learners to employment

One of the primary goals that adult learners enter school with is to enter or improve the quality of employment. Therefore, one of the core missions for all adult public charter schools is to provide employment services to learners.

At most schools, learners can receive support throughout their time at school to either find a job or to search for and apply for a better job. Employment services provide support by reviewing application materials, hosting mock interviews, reviewing resumes, and distributing career aptitude tests. Research shows that career assets similar to those offered by many adult charter schools, career exposure, career counseling, and connections to employers can improve employment opportunities.34

Adult public charter schools also often have direct connections to regional employers. For example, employers reach out to schools when they have vacancies, attend school-based job fairs, or participate in work-based learning classes. In interviews with school leaders, strong connections to employers in the area emerged as a strong employment facilitation strategy.

- At Briya PCS, learners enrolled in the Medical Assistant (MA) program complete their externship at Mary’s Center. During COVID-19, many healthcare providers paused their externship programs. Because of the strength of Briya PCS’s partnership, MA learners were able to continue their externships by participating in telemedicine appointments.

- Learners at The Family Place PCS who are aiming to earn their Childcare Development Associate (CDA) are connected to local childcare centers in D.C. Many learners seek employment at these centers after they have earned their credential, and the childcare centers reach out when they have open positions.

- Every student who finishes the workforce program at the LAYC Career Academy PCS does an externship followed by receiving job placement services. Learners in the medical assistant program complete a 160 hour externship with medical providers. Most learners who complete the full workforce program including classroom instruction and an externship are placed into jobs.

- Learners at Academy of Hope PCS’s healthcare program are placed with hospital partners and healthcare providers to complete 200 hours of training per semester. Most of the learners who enroll and complete the healthcare program are then employed with one of Academy of Hope PCS’s employer partners.

Social and economic supports

Adult learners balance competing responsibilities outside of education which can introduce barriers to learning and make persistence a challenge. The pandemic exacerbated many of these barriers.

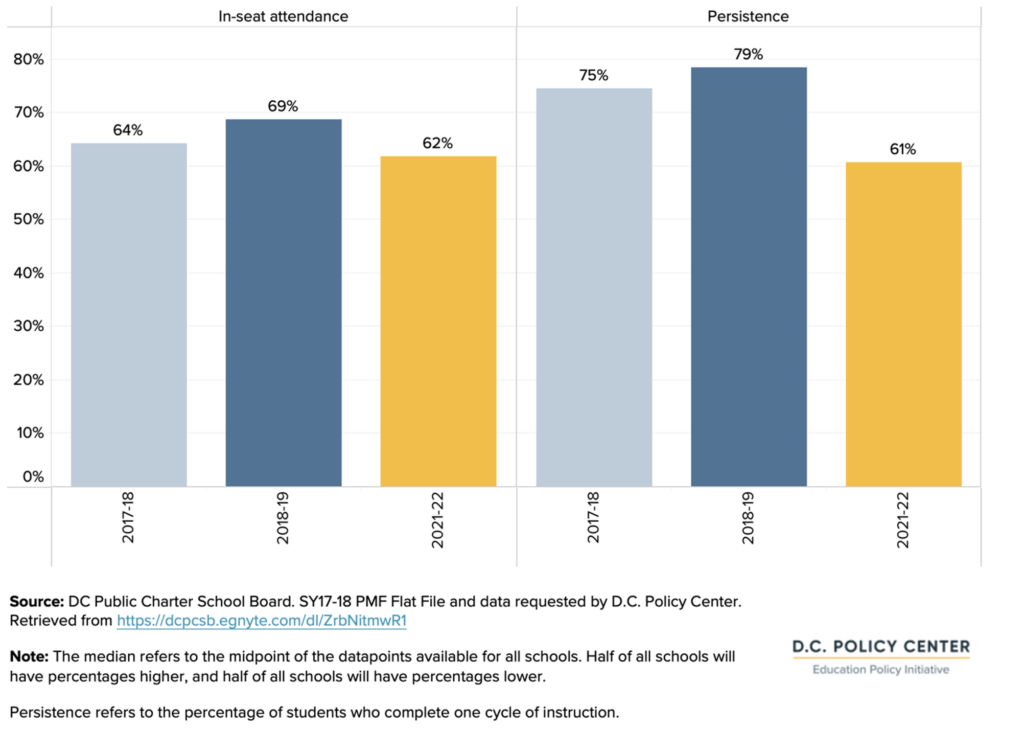

In-seat attendance was higher pre-pandemic than in school year 2021-22. In school year 2017-18, more than half of the adult public charter schools had an in-seat attendance rate of 64 percent, and in school year 2018-19, this rate rose to 69 percent. In school year 2021-22, this rate decreased to 62 percent.

The persistence rate, or the share of learners who stay enrolled long enough to complete one cycle of instruction, also decreased from 79 percent in school year 2018-19 to 61 percent in school year 2021-22.

Figure 12. Share of learners by engagement metrics at median adult public charter school

According to interviews with school leaders, economic pressures are the most common barriers for learners to complete their learning. When work schedules and school schedules conflict, adult learners often must choose work in order to continue supporting themselves and their families.

Because of the many challenges that adult learners face, school leaders expect that learners may have to pause their education at some time. Most adult public charter schools plan for such pauses and offer accommodations. For example, several schools offer rolling enrollment throughout the year so that learners may enroll when it works best for their schedule. Several school leaders mentioned that offering hybrid and virtual options had shown some success at keeping learners from completely stopping out or ending their enrollment completely.

When a student does stop out, most adult public charter schools work to maintain relationships with learners, address any barriers to enrollment, and offer an open opportunity to return at any time. School leaders prioritize maintaining strong relationships with learners, so learners know that they are welcome to return at any time to continue their education when it is a better time for them.

Adult public charter schools characterize social and economic support as critical for many adult learners to be able to remain or return to school. School leaders described an extensive case management system of support including an intake screening, connections to District and federal resources that can help provide support for housing, childcare, transportation, food assistance, and more. For example:

- Briya PCS is co-located with Mary’s Center, a community health center, in three of four sites so that learners can easily access supports such as mental health counseling or healthcare.

- Academy of Hope PCS partners with Capital Area Food Bank to host a market every month. Schools also may offer additional services directly.

- Community College Preparatory Academy PCS offers a boutique on-site for learners who need appropriate interview attire.

- Carlos Rosario International PCS works closely with agencies such as Latino Economic Development Center (LEDC), Clínica del Pueblo, and the Mayor’s Office on Latino Affairs to bring in workshops, fairs, and information sessions to support the specific needs of the schools’ students, the majority of whom are Latino.

- Several schools also run food pantries on-site for their learners.

In addition to providing resources, many school leaders described deliberate community building as a priority for their school. In some schools, especially those with a focus on serving immigrant populations, learners can be in community with those from similar backgrounds who speak a common language and are also navigating a new place. For example, Briya PCS offers a program that connects parents of similar age children who speak the same language for support and to share experiences of navigating the school system. Learners in adult public charter schools also can be enrolled in classes with different generations. While not easily measured, several school leaders said that learners benefitted greatly from participating in classrooms with those of different ages.

Supports for parents

Additionally, adult learners must also balance parenting responsibilities—54 percent of adult learners are also parents of school-age children.35 According to school leaders, many adult learners enter school with the goal of better supporting their children’s education by helping with content and by better communicating with their child’s teacher.

For parents of older children, some adult public charter schools assist learners with enrolling their children in D.C.’s public school system. School leaders describe how in some schools, ESL classes incorporate lessons on the vocabulary and the appropriate cultural norms for communicating with a child’s teacher. Several schools also offer seminars for adult learners on how to navigate D.C.’s public school common lottery, My School DC.

For parents of younger children, school leaders have identified that access to high-quality childcare is an obstacle to attending school. Several schools offer connections to childcare providers and resources to apply for childcare benefits, according to school leaders. Parents of younger children have access to two schools—Briya PCS and The Family Place PCS—have a two-generation approach where adult learners can enroll their children in pre-kindergarten classes at the same location. Adult learners join their children for collaborative play and learning for part of the day.

Briya PCS

Briya PCS uses a two-generation education model that supports educational and social-emotional well-being for parents and their children. Briya PCS’s early childhood program enrolls children from 6 weeks to 2 years old in an infant and toddler program and also offers high-quality pre-kindergarten for children ages 3 and 4. Each child also has a parent enrolled in Briya PCS’s ESL or workforce programs, and parents are invited into the classroom for collaborative experience to learn and grow alongside their child.[1] In addition to ESL classes, parents can also get support to earn their high school equivalency diploma through the NEDP and also receive services through partner organizations like Mary’s Center.

“I’m always so grateful to live and work where we can provide a holistic two-gen program that has the ability to work with both parents and young children in the same building and focus on quality education for both generations. […] It is just remarkable what can be done with commitment and a policy decision that was made so long ago to include adults and young children in its definition of public education.”

Christie McKay, Briya PCS

Supports during the pandemic

COVID-19 amplified economic stresses and introduced new concerns alongside the transition to virtual learning.36 Many adult learners are employed in sectors that experienced losses during the early pandemic–retail, health, and hospitality.37 In December 2022, 51 percent of learners who responded to a survey on adult public charter schools reported that they had lost their job at some point during the pandemic. An additional 30 percent had suffered a reduction in hours.

While adult public charter schools may improve learners’ employment prospects, this period of instability led to a loss of income, which may have caused additional stress on learners. In December 2020, 85 percent of respondents expressed that they had concerns about meeting their basic needs including employment, physical health, and housing.

In response to COVID-19, adult public charter schools provided additional supports for learners. Schools connected learners to DC CARES, a program designed to distribute cash assistance to D.C. residents who were not eligible for other federal COVID-19 aid.38 Several schools directly distributed food and supplies to learners. All school leaders described an increase in case management and continued outreach to learners to make sure their basic needs were being met. Seventy-three percent of respondents said that their schools helped them meet some or all of their non-academic needs, including emergency financial support, essential goods such as diapers, toiletries, and food staples. While school leaders described offering fewer supports as the impacts of COVID-19 lessened on learners, many nonetheless continue to offer some direct resource supports to students.

In addition to resource supports, adult public charter schools also responded to COVID-19 by identifying urgent needs related to continuing learning and instruction. Based on 2020 surveys of adult and alternative learners and interviews with school leaders, one of the key areas of concern for adult and alternative learners early in the pandemic was navigating technology. In the May 2020 survey, 62 percent of learners reported that challenges with technology made it difficult for them to learn from home. These challenges seemed to have lessened over time. By fall 2020, 82 percent of learners said that their ability to use technology had improved since spring 2020.39 Insights from school leaders reflect the same conclusions.

All school leaders interviewed described large-scale initiatives beginning in March 2020 to distribute devices such as laptops and tablets in order to continue learning. Additionally, they worked with learners to make sure that they had access to the internet either by distributing hotspots or connecting them to citywide resources that subsidized internet access during COVID-19. School leaders also initiated digital literacy programs, hired additional IT staff and support, and placed technology aides alongside teachers in virtual classes. School leaders described greater comfort with technology among learners as a bright spot amid a difficult transition to virtual education.

Carlos Rosario International PCS

At the beginning of the pandemic, Carlos Rosario International PCS, employment services staff assisted learners who needed support submitting job applications and preparing for job interviews that were held over Zoom. It was evident that the pandemic shutdown had the greatest impact on those who experience difficulty navigating digital environments. The school saw positive impacts on learners’ digital literacy development from instituting hybrid model, which continues as their primary modality for instruction.

“In pre-pandemic times, if learners missed classes they missed out on valuable instruction and would fall behind. Through the use of the school’s Learning Management System, students are now able to access their educational materials and engage in the day’s lesson if they missed class or if they want to review.”

Dr. Holly Ann Freso-Moore, Carlos Rosario International PCS

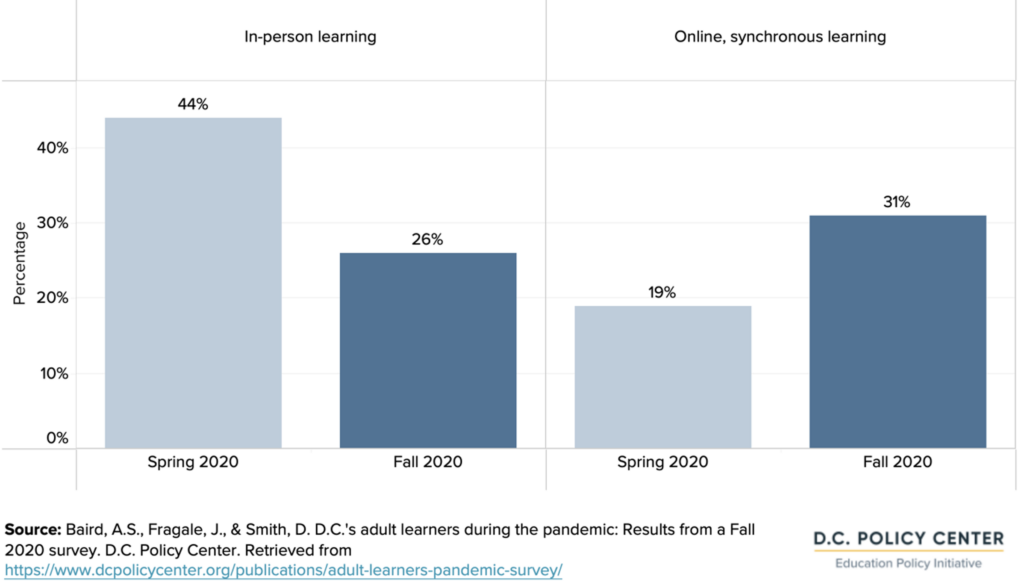

School leaders noted that after a year of virtual learning, several schools made the decision in school year 2021-22 to initiate hybrid schedules (two days in-person and two days virtual) or entirely virtual options, to better fit with adult learners’ preferences. School leaders reported that learners appreciated this increased flexibility with scheduling, childcare, and eliminating commute times. Survey findings from May and December 2020 support these findings. While in May 2020, 44 percent of learners indicated a preference for in-person learning, by December 2020, only 26 percent of learners indicated this preference. Conversely, the percent of learners who indicated a preference for virtual, synchronous learning increased by 12 percentage points.

Figure 13. Changes in learning preference, spring to fall 2020

Conclusion

Adult public charter schools serve a large and specific population across the city. In school year 2022-23, nine adult public charter schools served 5,144 learners in D.C., representing 5 percent of all public school students in D.C. Of those enrolled, 42 percent are Black, 55 percent are Latino, and 2 percent are white. Seventy percent of adult learners speak a language other than English at home. Adult learners reside across the city, with the highest number of learners residing in Wards 4 and 8, and Ward 1 having the highest concentration of school locations with six adult public charter schools.

Many adults in D.C. would benefit from additional qualifications. Twenty-five percent of D.C.’s public school students do not graduate from high school, and across the city, 7 percent of D.C. residents aged 25 and older do not have a high school diploma. However, earning a high school diploma in D.C. is associated with access to more jobs within the District and higher incomes. Ninety-six percent of jobs in D.C. require at least a high school diploma or some postsecondary education, and income is at least $5,000 higher for D.C. residents who have a high school degree compared to those who do not. Incomes rise even more for those with at least some postsecondary education.

Adult public charter schools provide a bridge between high school, and college and workforce programs. For those seeking additional education or who are interested in becoming proficient in English, eight schools offer academic programs including: supports to earn a high school equivalency certificate such as the NEDP or GED; instruction in literacy and numeracy; English language instruction; and supports and connections to pursue additional postsecondary education. All nine schools offer workforce supports, including credential-granting programs in high-demand fields; ability to earn career assets such as work-based learning or career exposure; and connections to employers.

Some adult learners face barriers to learning, most commonly related to economic pressures and stresses. Many adult learners must prioritize work and family responsibilities over school. If work schedules change, childcare availability is limited, or economic pressures at home require that an adult learner work additional hours, adult learners may pause their education with plans to resume at a different time.

Adult public charter schools provide supports to enable persistence and the ability to return to education and workforce programs. Strategies include offering rolling enrollment, hybrid schedules, and open opportunities to re-enroll; providing case management support; and prioritizing community building within the school. During COVID-19, many schools offered additional supports, including technology disbursement programs to encourage students to persist through virtual education as well as non-academic supports like food distributions.

Adult public charter schools serve a unique population who may need more supports and different programming than is available at high schools, community colleges, or workforce programs. Adult public charter schools allow adults to earn high school diplomas and equivalency certificates, as well as connections to postsecondary and workforce opportunities. In turn, these outcomes may lead to more access to the types of jobs that are most available in D.C.’s economy.

Appendix

Table 1: Adult public charter school workforce and academic offerings, as of November 2022

Table 2: Characteristics of other adult-serving public schools in D.C.

Table 3: Characteristics of adult public charter schools in D.C.

Endnotes

- D.C. categorizes adult education as services or instruction below the college level for adults who “lack sufficient mastery of basic educational skills to enable them to function effectively in society”; do not have a certificate of graduation from a school providing secondary education, or those who have limited abilities in English. In D.C., many adult public charter schools serve a combination of those who are categorized as adult and alternative learners. For the purposes of this report, we will be referring to D.C.’s adult public charter schools as those who serve a population over the age of 16 and will be referring to those enrolled at one of the nine identified schools as “adult learners”.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2022. S1501|Educational Attainment. 2021 American Community Survey 1-year estimates. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/table?q=high+school+diploma+dc+2021&tid=ACSST1Y2021.S1501

- In 2017, an estimated 22 percent of adults ages 16-74 read at or below a level 1 on the PIACC scale which means reading using basic vocabulary, determining meaning of sentences, and reading paragraphs. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), 2012/2014/2017. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/piaac/skillsmap/src/PDF/STATE.pdf

- D.C. Policy Center analysis of National Center for Education Statistics Common Core of Data, Membership file for school year 2021-22. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/files.asp#Fiscal:2,LevelId:2,SchoolYearId:36,Page:1

- Council of the District of Columbia. Code of the District of Columbia, Title 38, Subtitle IV, Chapter 18. Retrieved from https://code.dccouncil.gov/us/dc/council/code/titles/38/chapters/18/subchapters/II/

- Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education (DME) and DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education. 2021. 2021-22 School Year Uniform Per Student Funding Formula. Retrieved from https://osse.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/osse/publication/attachments/2021-22%20Uniform%20Per%20Student%20Funding%20Formula%20Payments.pdf

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2022. S1501|Educational Attainment, 2021 American Community Survey 1-year estimates. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/table?q=earnings+education+dc+2021+&tid=ACSDT1Y2021.B20004

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2017-2021 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, S1501 Educational Attainment. Retrieved from data.census.gov

- DC Public Charter School Board. 2018-19 School Quality Reports. Retrieved from https://dcpcsb.egnyte.com/dl/JAxsaJlSO5

- Data sent by OSSE. Data request did not include information from Maya Angelou – Young Adult Learning Center.

- . Census Bureau. 2022. B03002|Hispanic or Latino Origin by Race. 2021 American Community Survey 1-year estimates. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/table?q=+latino+dc+2021+&tid=ACSDT1Y2021.B03002

- D.C. Policy Center. 2023. State of D.C. Schools, 2021-22. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/schools-21-22/

- The frequency of programs offered is based on listings on each school’s website supplemented with findings from interviews with school leaders. This does not reflect how many learners are enrolled in each program, which is not publicly available. It also does not reflect on the completion of each program. While schools are required to report how many learners complete programs and how many learners earn industry-recognized credentials, schools are not required to publicly report these figures by school or program.

- Adult public charter schools refer to English language classes as both English as a Second Language (ESL) and English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL). This report will refer to both as ESL classes.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2022. S1501|Educational Attainment, 2021 American Community Survey 1-year estimates. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/table?q=high+school+diploma+dc+2021&tid=ACSST1Y2021.S1501

- D.C. Policy Center. 2023. State of D.C. Schools, 2021-22. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/schools-21-22/

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2022. Occupational Employment Statistics. “February 2023 data: State”. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/oes/ – data

- Expected educational attainment by occupation is based on data from the National Center for O*NET Development, which is sponsored by the U.S. Department of Labor (https://www.onetonline.org/). Educational attainment requirements by occupation were matched by occupation code to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data on the number of jobs for each occupation in D.C.

- The National External Diploma Program (NEDP) is a nationally recognized assessment program for adults and out-of-school youths. Students complete a series of assignments covering a variety of subjects. Rather than a single or series of tests, students complete the assignments online in order to earn a high school equivalency diploma. CASAS. 2022. National External Diploma Program (NEDP). Retrieved from https://www.casas.org/nedp

- DC Public Charter School Board. 2019. 2019 School Quality Report. Retrieved from individual school pages from https://dcpcsb.org/school-profiles

- Six of the nine adult public charter schools reported scores for this metric for school year 2021-22; seven schools reported scores in school year 2017-18. Data for school year 2021-22 was sent from the Public Charter School Board in response to a D.C. Policy Center data request.

- DC Workforce Investment Council. 2022. ACCESS DC! A guide to navigating programs and services in the District of Columbia. Retrieved from https://osse.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/osse/page_content/attachments/ACCESS%20DC-A%20Guide%20to%20Navigating%20Programs%20and%20Services%20in%20the%20District%20of%20Columbia.2022.pdf

- DC Public Charter School Board. 2019. 2018-19 School Quality Reports. Retrieved from https://dcpcsb.egnyte.com/dl/JAxsaJlSO5

- One test used by many adult learning programs is CASAS,the OSSE-mandated assessment used to measure ABE, and ESL for adult learner programs that are funded by the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). 2020. DC Assessment Policy for Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) Providers and Core Partners V.3.1. Retrieved from https://osse.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/osse/page_content/attachments/DC%20OSSE%20AFE%20Assessment%20Policy%20for%20WIOA%20Providers%20and%20Core%20Partners%203.1.pdf

- One test used by many adult learning programs is CASAS,the OSSE-mandated assessment used to measure ABE, and ESL for adult learner programs that are funded by the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). https://osse.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/osse/page_content/attachments/DC%20OSSE%20AFE%20Assessment%20Policy%20for%20WIOA%20Providers%20and%20Core%20Partners%203.1.pdf

- University of the District of Columbia. 2012. Articulation agreement – Career/technical education program. Retrieved from https://docs.udc.edu/aa/articulation/UDC-CC%20Articulation%20FSEM%20and%20APCT%20with%20Academy%20of%20Hope%20PCS%20-%20Signed.pdf

- DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). 2023. DC Dual Enrollment Consortium Program: Participating LEAs. Retrieved from https://osse.dc.gov/page/dc-dual-enrollment-consortium-program-participating-leas

- DC Workforce Investment Council. 2021. FY21 Workforce Development System Expenditure Guide Accompanying Document – February 2022. Retrieved from https://dcworks.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dcworks/publication/attachments/FY21-Accompanying-Document.pdf

- DC Workforce Investment Council. 2021. FY21 Workforce Development System Expenditure Guide Accompanying Document – February 2022. Retrieved from https://dcworks.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dcworks/publication/attachments/FY21-Accompanying-Document.pdf

- DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). 2020. OSSE and WIC announce the winners of the Adult and Family Education Consolidated Competition Grant. Retrieved from https://osse.dc.gov/publication/osse-and-wic-announce-winners-adult-and-family-education-consolidated-competitive-grant

- In addition to the adult public charter schools listed, the other grant recipients are: Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Washington, Congress Heights Community Training and Development Corporation, Four Walls Career and Technical Education Center; Opportunities Industrialization Center-DC, So Others Might Eat (SOME) Center for Employment Training, Southeast Welding Center, Inc., and YWCA National Capital Area.

- Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education (OCTAE). 2023. Accountability and Reporting – Adult Education and Literacy. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ovae/pi/AdultEd/accountability-reporting.html

- Farrell, R. and Lawhorn, W. 2022. “Fast-growing occupations that pay well and don’t require a college degree.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2022/article/occupations-that-dont-require-a-degree.htm

- Calma, E. 2021. D.C. high school alumni reflections on their early career outcomes. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/early-career-brief/

- Simpson Baird, A., Fragale, J. & Smith, D. 2021. D.C.’s adult learners during the pandemic: Results from a Fall 2020 survey. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/adult-learners-pandemic-survey/

- Simpson Baird, A., Fragale, J. & Smith, D. 2021. D.C.’s adult learners during the pandemic: Results from a Fall 2020 survey. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/adult-learners-pandemic-survey/

- Simpson Baird, A. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on D.C.’s adult learners: Results from a Spring 2020 survey. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/covid-adult-learners-survey/

- DC Cares. 2021. DC CARES funding is now available. Retrieved from https://production.powerappsportals.com/eng-dcc-2021

- Simpson Baird, A., Fragale, J. & Smith, D. 2021. D.C.’s adult learners during the pandemic: Results from a Fall 2020 survey. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/adult-learners-pandemic-survey/