Rising community violence in the District is exacerbating the academic and socio-emotional issues students D.C. students face as they recover from effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. How can schools, in collaboration with the broader D.C. community, be part of the solution and extend their reach in supporting students holistically?

Children in D.C. are exposed to more community violence than their peers elsewhere

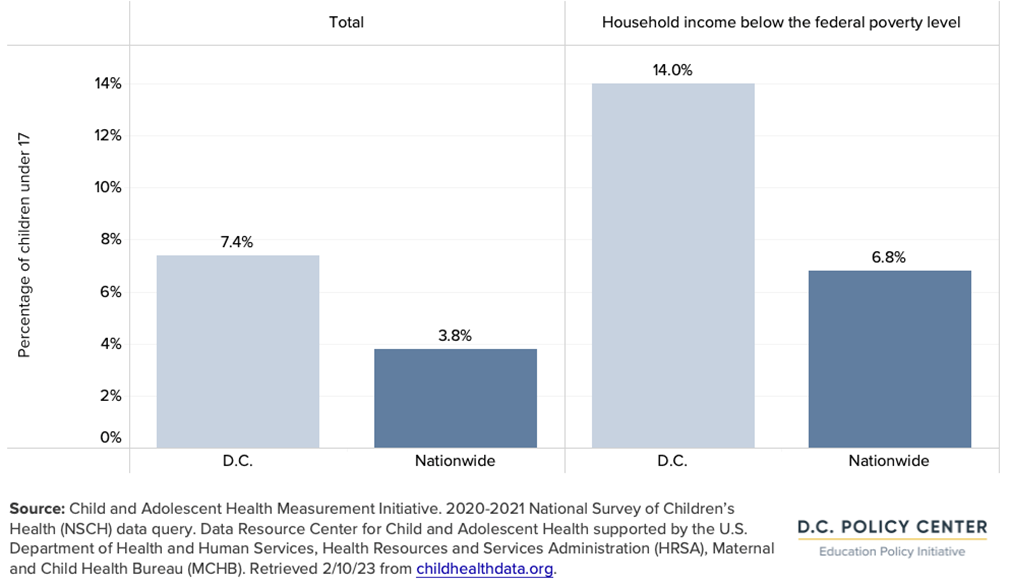

Compared to their counterparts across the country, children and youth aged 17 and younger living in D.C. are more likely to be exposed to violence. In 2020 and 2021, 7.4 percent of D.C. children and youth were victims of, or witnessed, violence in their immediate neighborhoods. This is almost double the national average of 3.8 percent.1 Among households living below the federal poverty level, exposure is even higher: 14 percent of children in these households are a victim or witness of neighborhood violence, compared to 6.8 percent of children nationwide.

Direct exposure to community violence is notably a self-reported issue for D.C.’s middle and high school students: According to the 2021 National Youth Risk Behavior survey, 37 percent of middle school and 27 percent of high school students, respectively, recounted seeing and hearing violence or abuse where they live.2

Figure 1. Percentage of D.C. children who were a victim of or witness to neighborhood violence, school year 2020-21

Recent research and reports uncover even more reason for concern. An analysis3 shows that in 2021, nearly 80 percent of D.C. residents lived within a half mile of a homicide and about two-thirds of D.C. residents lived within a half mile of multiple homicides—and that these homicides are more likely to occur in areas where most children live in D.C. Proximity to violence is very common for residents across the city.

“I am deeply concerned about community safety. Every year we have current or former students shot and injured or murdered. Our kids witness acts of violence. The neighborhood rivalries are an ever present threat in and outside of the school building. We need help.”

D.C. Principal

While year-to-date crime decreased across nearly all categories in 2022,4 violent crime is still higher than it has been in many recent years. For example, 2022 had the most homicides since 2003. Homicides are the culprit for the majority of deaths for people aged 15-34 in D.C. In 2021, almost all homicide victims were Black.5

Why exposure to community violence matters as an Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE)

According to the 2020-2021 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH),6 39 percent of all children in the United States (and 38 percent of children in D.C.) experience at least one Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) before they are 18 years old. These negative experiences include any form of abuse, living with an adult who has a mental illness, poverty, incarceration, discrimination, and more. These traumatic experiences and events can have a debilitating impact upon children and their development well into adulthood, especially when accumulating ACEs are compounded.7

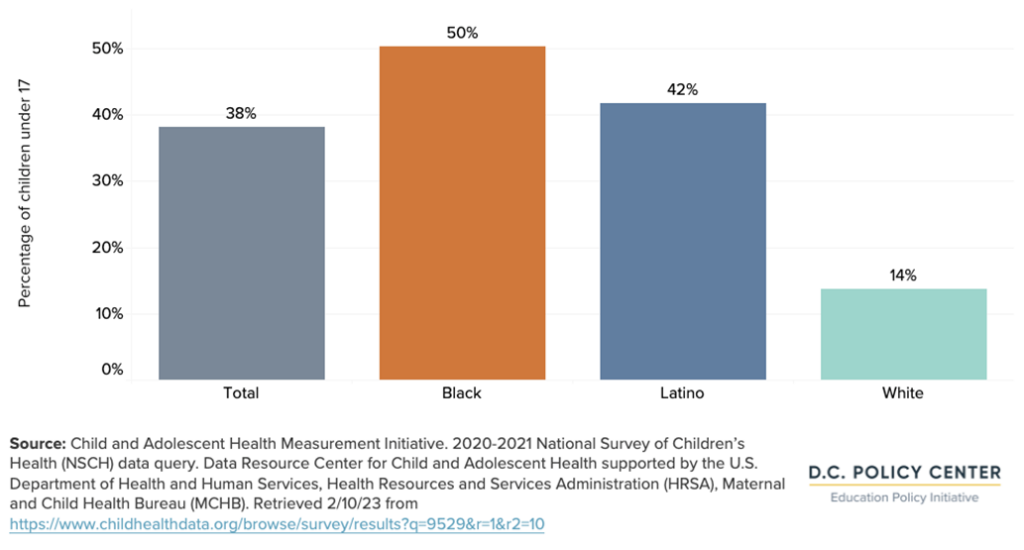

While ACEs themselves are indiscriminate to demographic factors, the research underscores the disparities are clearly entangled with the constructs of systemic racism and oppression in our country. Specifically, 50 percent of Black non-Hispanic children and 42 percent of Latino children living in D.C. have experienced at least one ACE, compared with 14 percent of white children as of 2020-2021.8 These numbers illustrate yet another weight Black and brown students tote daily and must ultimately overcome.

Figure 2. Percentage of children in D.C. who have experienced one or more Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) by race and ethnicity, 2020-21

Impact of exposure to community violence on learning

Whether exposed to violence regularly or as a single event, research9 illustrates that community gun violence has long-term, negative effects on students’ academic performance and their overall health and well-being. Witnessing acts of violence during childhood can create traumatic psychological symptoms, such as anxiety and emotional dysregulation. In fact, one in four children exposed to traumatic events develops post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by age 18, while this prevalence is even higher among young people who have been exposed to armed conflict.10

Exposure to violence can have significant effects on mental health and academic achievement. The Youth Risk Behavior Survey shows an uptick in D.C.’s high school students who are feeling sad or hopeless: as of 2021, 36 percent felt this way consistently for the past two weeks, up from 33 percent in 2019 and 27 percent in 2017.11 When these adverse symptoms continue for extended periods of time, it can weaken young people’s academic achievement and social skill development. Research12 also shows that higher levels of gun violence in the community are also significantly associated with higher rates of failure on Math and English proficiency tests. Sometimes, feeling unsafe can directly result in staying home from school: in 2021, 8 percent of D.C.’s high school students reported doing so in the past 30 days.[xiii]13

“As a principal, it is disheartening to see the amount of violence which happens within the community surrounding my school. The amount of violence has a direct impact on the trauma our students experience which can have a direct impact on students’ academic success.”

D.C. Principal

Per the PARCC (Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) and the Multi-State Alternate Assessment (MSAA), the large majority of Washington, D.C. students are behind academically. In 2022,14 69 percent of students Grades 3-12 performed below grade-level expectations for English Language Arts (ELA) and 81 percent of students performed below grade-level expectations in Mathematics. The proficiency rate of at-risk15 students decreased more than the rate of not at-risk students, in both Math and ELA, from 2019 to 2021.

While these reports of learning loss are concerning, COVID-19 school closures and extended virtual learning must be taken into account. Notably, D.C. schools have launched significant recovery efforts to stabilize schools and invest funding towards students’ academic and overall well-being, including high-impact tutoring and staffing provisions, to name a few.

Notwithstanding, it is important to consider the complex and nuanced work of educating students in our nation’s capital. It can be difficult for students to focus on learning Algebra and well-written essays if they are in a perpetual fight-or-flight response due to threats and reports of community violence. This additional variable toward recovery efforts for D.C. students must not be overlooked.

With support, schools can help mitigate the impact of community violence and trauma

Thankfully, not all children who experience ACEs during their formative years are negatively affected. Schools can leverage their positions to strengthen communities and students’ lives. Specifically, research suggests there are school-level characteristics that can help offset the risks and negative consequences that adversity can impose. Some transformative practices include:

- Supportive and dedicated personnel: Studies indicate that positive relationships can have a remedying impact for youth trauma.16 Strong attachments with adults at school – including teachers, staff, coaches, administrators – help to provide young people with a sense of safety, security, and stability. Deepening connections with students through mentoring, after-school programs, and the like can be particularly important when students experience insecurity at home.

- Positive school culture & effective behavior management: Among many other benefits, research17 asserts schools that employ mental health providers experience lower rates of serious disciplinary incidents overall. Specifically, guidance counselors can help students with coping strategies and long-term planning. Psychologists evaluate and help diagnose student cognitive needs, while social workers can facilitate access to therapy and community resources.

In D.C. schools, rates of suspension and expulsion have significantly declined from high levels over the years.18 Legislation19 and overall consciousness-raising regarding the ineffectiveness of these exclusionary practices continue to compel educators to favor restorative and trauma-informed practices, such as mediations/circles and social-emotional development.

- Solid, well-rounded instruction: In particular, studies20 suggest that positive school environments can help fortify vulnerable children with empowering mindsets and capabilities. By providing high-quality instruction as early as pre-school can give students a strong foundation for years to come boosts their high school graduation and college attendance rates.21 It is possible to help students overcome their ACEs by affording them with holistic education which will last through years as they heal and are empowered to explore their own paths.

- Family and community engagement: Research22 shows a strong relationship between schools and families can lead to positive outcomes for students. As schools maintain reciprocity and authentic interest with families and community members, students reap the benefits of these associations and partnerships.

“I think the more that schools, other district agencies, and community agencies collaborate, the safer the communities that surround our school will be.”

D.C. Principal

“We all should work in tandem. However, the school is often the hub by default. Hence, additional and adequate resources should be allocated to schools to ensure that we can maintain safety for all scholars and staff.”

D.C. Principal

As principal of a D.C. elementary Title 123 school, it is painful to know what my students have seen, heard, and witnessed. As young as three years old, some of my students have learned to decipher the sound of gunshots in their communities. They have lost parents, siblings, and loved ones to homicides. They have heard the stories of senseless violence in their neighborhoods. Playing outside is not always allowed for fear of being at the wrong place at the wrong time. The stories they have recounted are haunting and the questions they ask leave me speechless. I empathize with the terror and hurt I see in my families’ eyes as well. They wish to protect their children from the harsh realities of the streets. Parents and guardians want a better life for them, beyond the violence and despair, but wonder if the cycles they have seen for generations will ever end.

We initiated a Tyler Elementary Community Safety Hub in Spring 2022. With vested members in the neighborhood and several partners, we convene monthly to discuss observational trends and most importantly, how we can work together to embrace our community with actionable events and initiatives. When well-synchronized in collaboration with numerous agencies and organizations, including education, housing, healthcare, legislators, law enforcement, and others, we can all collectively help reduce community violence.

For many D.C. students who are exposed to violence, the load they carry is becoming heavier by the day. They face numerous challenges, but we are all on a mission to help them succeed both now and in the future. Our students are naturally resilient and this asset—one of many—should fuel and inspire us collectively to educate and advocate with their best interests in mind. By employing collaborative measures of prevention and intervention, D.C. students can and will achieve as we safely unite our D.C. community with healing and hope.

Endnotes

- Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. 2020-2021 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) data query. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). Retrieved January 8, 2023, from https://www.childhealthdata.org/browse/survey/results?q=9535&r=10

- Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). (2022). 2021 District of Columbia Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://osse.dc.gov/node/1635216

- Din, A. (2022, June 23). Proximity to homicide exposure in Washington, D.C. D.C. Policy Center. https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/homicide-exposure-maps/

- Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). (2023). District Crime Data at a Glance: 2023 Year-to-Date Crime Comparison. Metropolitan Police Department. Retrieved January 8, 2023, from https://mpdc.dc.gov/page/district-crime-data-glance

- United States Department of Health and Human Services (US DHHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Underlying Cause of Death by Single Race 2018-2021 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released 2022. Retrieved from https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html

- Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. 2020-2021 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) data query. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.childhealthdata.org/browse/survey/results?q=9529&r=1&r2=10

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (2019). REPRINT OF: Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American journal of preventive medicine, 56(6), 774–786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.001

- Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. 2020-2021 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) data query. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.childhealthdata.org/browse/survey/results?q=9529&r=1&r2=10&g=1009&a=17788

- Bergen-Cico, D., Lane, S. D., Keefe, R.H., Larsen, D.A., Panasci, A., Salaam, N., Jennings-Bey, T., & Rubinstein, R.A. (2018). Community Gun Violence as a Social Determinant of Elementary School Achievement. Social Work in Public Health, 33(7-8), 439-448, https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2018.1543627

- Danese, A., McLaughlin, K. A., Samara, M., & Stover, C. S. (2020). Psychopathology in children exposed to trauma: detection and intervention needed to reduce downstream burden. BMJ, 371(3073). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3073

- Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). (2022). 2021 District of Columbia Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://osse.dc.gov/node/1635216

- Bergen-Cico, D., Lane, S. D., Keefe, R.H., Larsen, D.A., Panasci, A., Salaam, N., Jennings-Bey, T., & Rubinstein, R.A. (2018). Community Gun Violence as a Social Determinant of Elementary School Achievement. Social Work in Public Health, 33(7-8), 439-448, https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2018.1543627

- Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). (2022). 2021 District of Columbia Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://osse.dc.gov/node/1635216

- https://osse.dc.gov/release/osse-releases-dc-statewide-assessment-results-after-two-year-pandemic-pause Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). (2022, September 2). OSSE Releases DC Statewide Assessment Results After Two-Year Pandemic Pause. Retrieved January 8, 2023, from https://osse.dc.gov/node/1635216

- Students who are at risk are those who qualify for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), have been identified as homeless during the academic year, who under the care of the Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA or “foster care”), and who are high school students at least one year older than the expected age for their grade. See more here: https://osse.dc.gov/page/data-and-reports-0#:~:text=Students%20who%20are%20at%20risk,and%20who%20are%20high%20school

- Bethell, C., Jones, J., Gombojav, N., Linkenbach, J., Sege, R. (2019, September 9). Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Mental and Relational Health in a Statewide Sample: Associations Across Adverse Childhood Experiences Levels. JAMA Pediatr. 173(11). Retrieved January 29, 2023, from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2749336?utm_campaign=articlePDF&utm_medium=articlePDFlink&utm_source=articlePDF&utm_content=jamapediatrics.2019.3007

- Aclu, M., Blinder, A., Cobb, J., Coyle, S., Greytak, E., Hinger, S., Johnson, G., Jordan, H., Mann, A., Mizner, S., Sun, W., Torres-Guillén, S., Whitaker, A. (2019, March 4) Cops and No Counselors How the Lack of School Mental Health Staff is Harming Students. American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/030419-acluschooldisciplinereport.pdf

- Marinelli, J. (2022). “Education Under Armed Guard”: An Analysis of the School-to-Prison Pipeline in Washington, D.C. American Criminal Law Review, 59(1697) (1698-1797. Retreived January 8, 2023, fromhttps://www.law.georgetown.edu/american-criminal-law-review/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2022/05/59-4_Marinelli-education-under.pdf

- Student Fair Access to School Amendment Act of 2018, D.C. Law 22-157 (2018). https://code.dccouncil.gov/us/dc/council/laws/22-157

- Christle, Christine A., Jolivette, K., Nelson, C.M. (2005) Breaking the School to Prison Pipeline: Identifying School Risk and Protective Factors for Youth Delinquency, Exceptionality, 13(2), 69-88. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327035ex1302_2

- Gray-Lobe, G., Pathak, P.A., & Walters, C.R. (2022). The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 138(1), 363-411. Retrieved January 8, 2023, from https://www.nber.org/papers/w28756?utm_source=npr_newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_content=20210517&utm_term=5393820&utm_campaign=money&utm_id=46842767&orgid=&utm_att1=money

- American Psychological Association. (2014). What is Parent Engagement? https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/programs/safe-supportive/parental-engagement

- Title Ischools are schools in which children from low-income families make up at least 40 percent of enrollment are eligible to use Title I funds to operate schoolwide programs that serve all children in the school in order to raise the achievement of the lowest-achieving students. (https://www2.ed.gov/programs/titleiparta/index.html)