To aid with pandemic recovery in D.C.’s schools and meet students’ needs, the combination of an influx of $540 million in ESSER federal grants for recovery, local non-formula resources, and increases to the student funding formula base (UPSFF) has contributed to a 56 percent increase in funding for schools between fiscal years 2019 and 2024 while enrollment grew by 9 percent. This additional funding has allowed D.C. schools to hire additional staff, promote accelerated learning activities and strategies, support student and staff well-being, and more. However, ESSER federal grants will end in September 2024 (with an extension for some spending). There is also significant uncertainty around the renewal of local non-formula funds.

This report explains the sources of growth in school budgets, indicators of future fiscal distress, continued need for recovery for D.C.’s students, and city-level factors that could influence future budgets, closing with suggested strategies for future school spending.

Quick Links

- Access a printer-friendly PDF version of the full report here.

- Access the 1-page report summary here.

- View the launch event, here.

Executive Summary

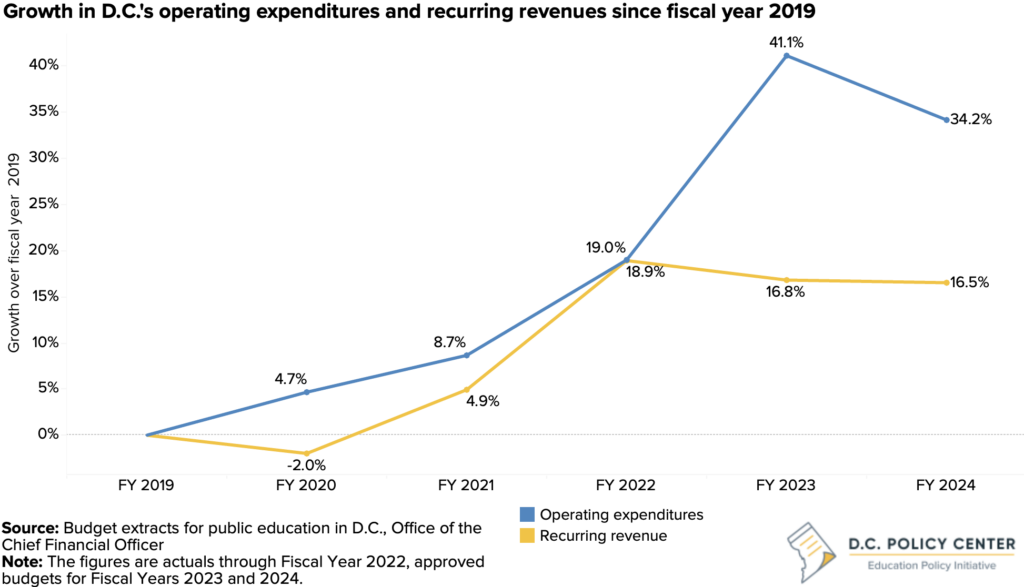

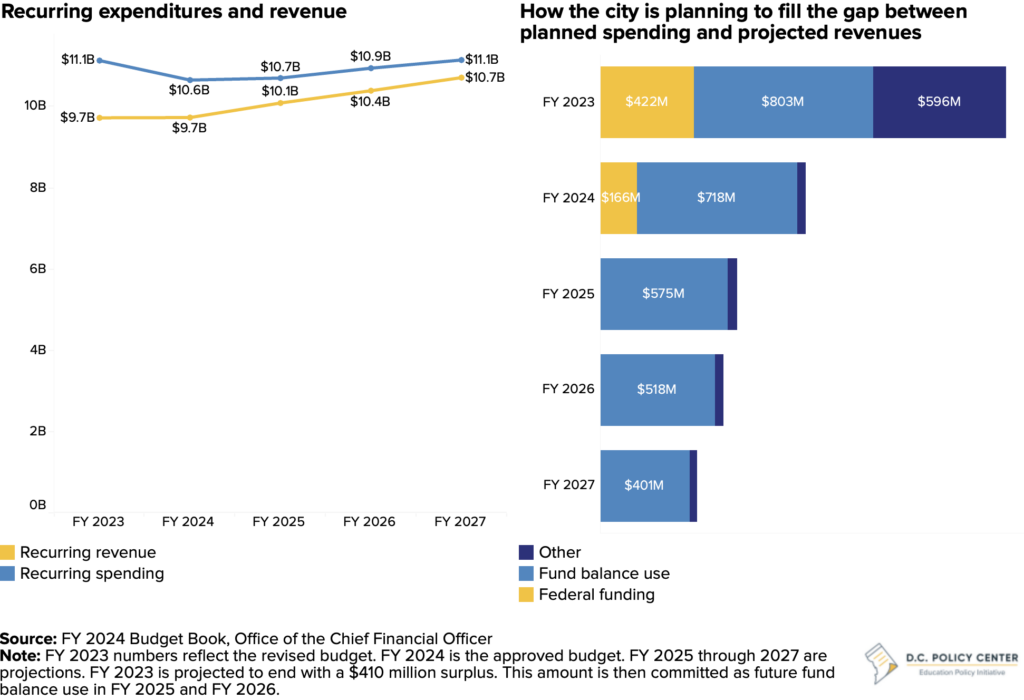

The fiscal landscape of the District of Columbia has experienced a significant transformation in recent years. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic’s swift and adverse impact on residents and the economy, the District’s finances initially remained strong, buoyed by a substantial federal fiscal aid package during fiscal years 2020-2024. Federal aid, coupled with substantial reserves, allowed the city to grow its local budget by 34 percent between fiscal years 2019 and 2024, while the city’s local revenues grew half as fast at 17 percent.

Throughout the pandemic, school budgets became increasingly reliant on non-formula funds.

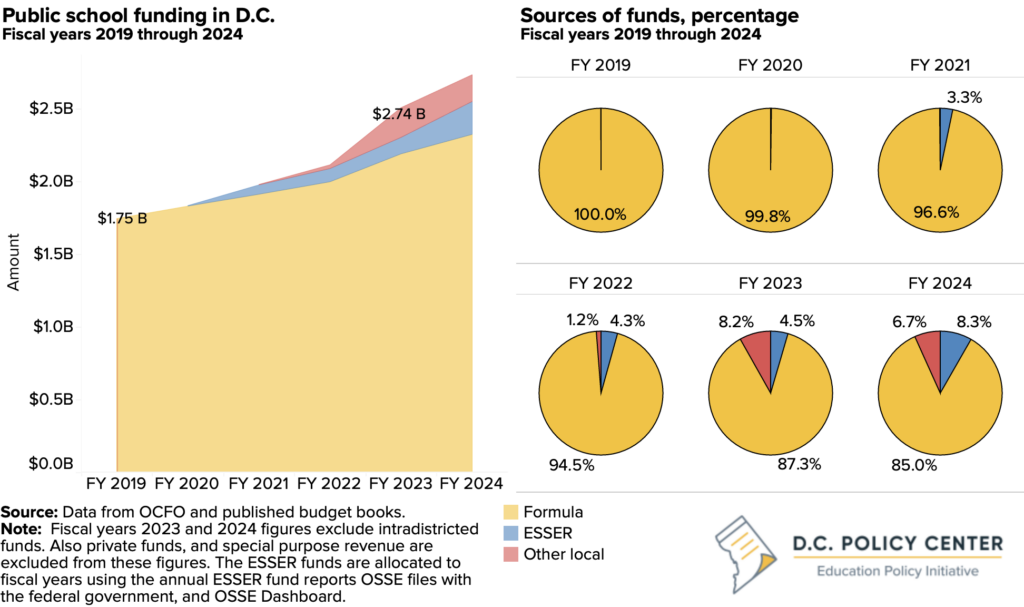

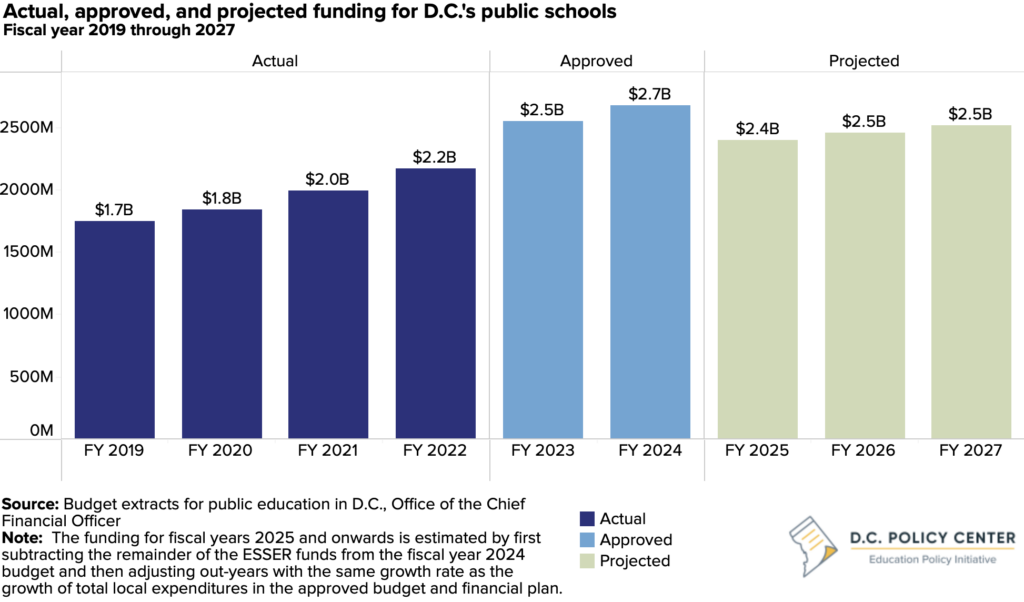

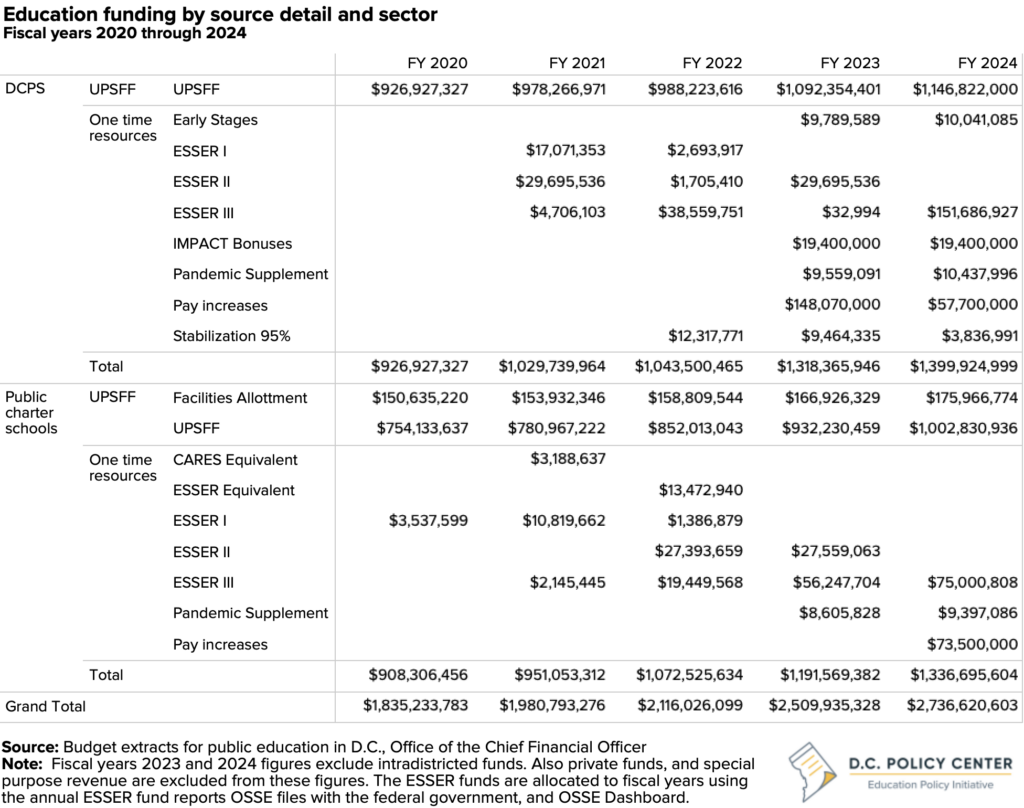

Public school funding in D.C. has grown even faster than the general city budget. From fiscal year 2019 to fiscal year 2024, local education agency (LEA) budgets, which include both the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) and public charter schools, increased from $1.7 billion to at least $2.7 billion. The budgets show a 56 percent increase in spending while student enrollment grew by approximately 9 percent in the same period.

Growth in school budgets was not solely due to increases to the Universal Per Student Funding Formula (UPSFF). It also resulted from federal fiscal aid like the Elementary and Secondary Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER) and additional local funding LEAs received for various purposes including budget stabilization, pandemic supports, and negotiated teacher salary increases (in the case of DCPS) and other salary increases (in the case of charter LEAs). Prior to fiscal year 2021, these non-formula dollars made up a negligible share of LEA budgets. However, by fiscal year 2024, their share had increased to an estimated 15 percent.

ESSER and most of the local non-formula funds are expiring in fiscal year 2025, leaving schools with significant resource gaps. It will be difficult to make up for these gaps through a formula funding increase. The District government itself will no longer have access to federal fiscal aid, and the city will have to tackle additional fiscal challenges such as weakening revenues, declining reserves, and a budget gap at the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA). As a result, LEAs must now prepare and develop strategies to dampen the consequences of the impending fiscal cliff.

The two key sources of future fiscal distress are enrollment and staffing.

While all schools will face tough decisions in fiscal year 2025, schools serving a larger share of economically disadvantaged students, especially at earlier grade bands, will face greater fiscal distress. LEAs with a larger population of economically disadvantaged students received larger amounts of ESSER funds, as ESSER funds were weighted more heavily for economically disadvantaged students. These LEAs will see larger gaps when ESSER funds expire. Future enrollment growth can ease some of this fiscal pain, but schools serving earlier grade bands did not see any enrollment growth in recent years. Key indicators—declining births and weakening cohort retention rates—suggest this will continue to be the case in the next few years to come.

Another indicator of future fiscal distress is staffing growth. Between school years 2019-20 and 2022-23, total enrollment across all LEAs that were eligible for ESSER funds grew by 333 students, while staffing (including teachers and other types of employees) grew by over 1,631.1 LEAs that have used a larger share of their temporary funding to expand staff will likely have to cut positions, which might disrupt school programs and learning.

Despite significant investments in recovery-related programs, full academic recovery is far from complete.

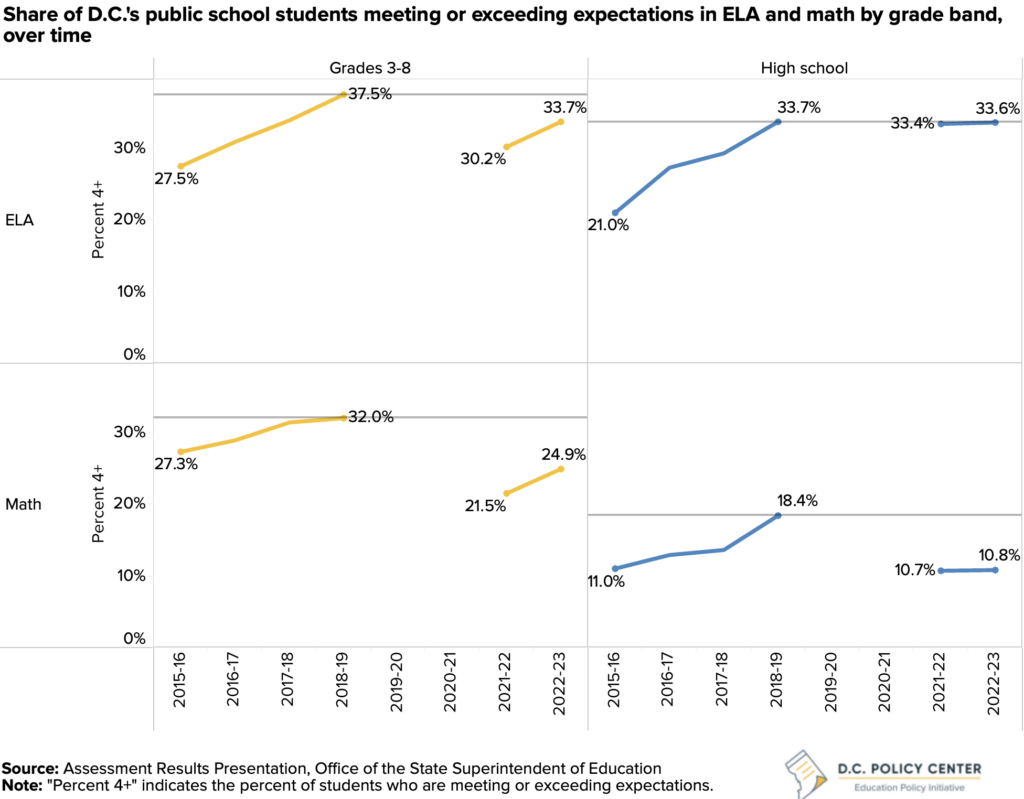

Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for Collage and Careers (PARCC) scores on the statewide assessment suggest returning to pre-pandemic academic achievement levels may take many years, particularly for high school students. Elementary and middle school students showed some improvement in English Language Arts (ELA) and math scores. However, high school students have not shown progress, with current proficiency levels comparable to or worse than those from several years ago. Slow improvement rates suggest a prolonged recovery period during which students will need additional supports but funding will be unavailable.

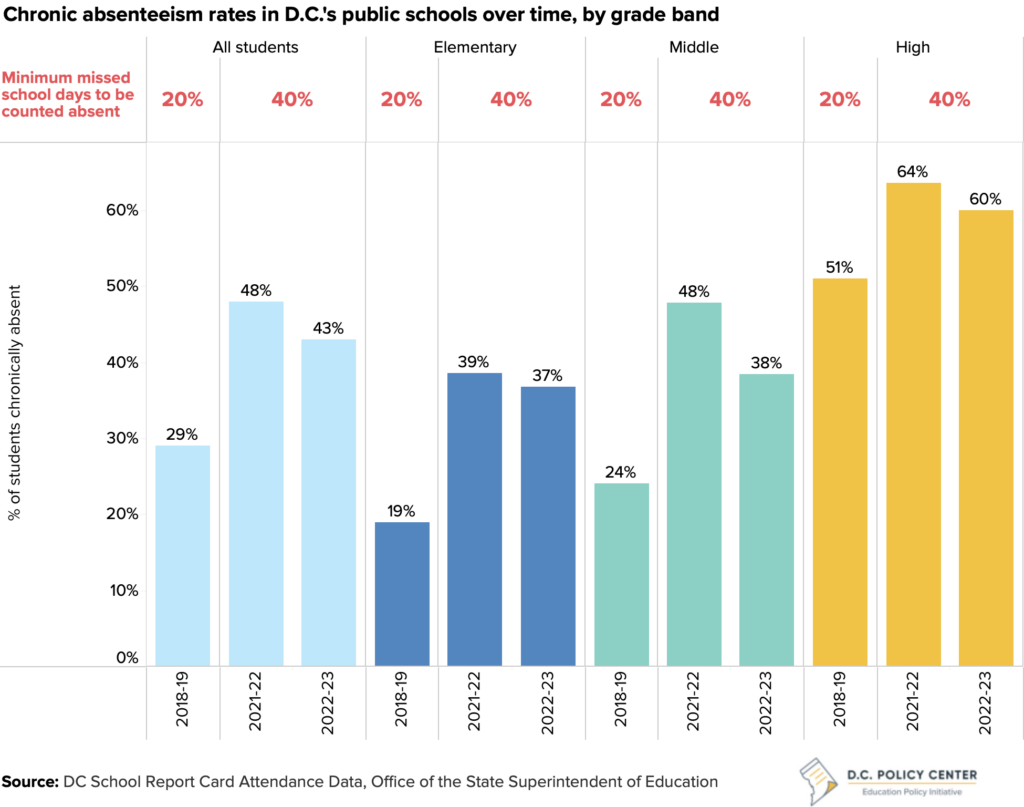

Compounding the challenges around academic recovery, 44 percent of students were chronically absent (missing 10 percent of school days or more) in school year 2022-23. This marks a significant increase from the last school year prior to the pandemic (school year 2018-19) when 29 percent of students were chronically absent. This comparison is further complicated by a recent change in the District’s absenteeism policy, which increased the share of the school day a student can miss before being counted as absent from 20 percent to 40 percent.

Chronic absenteeism is particularly acute among high school students. Across D.C.’s high schools, 60 percent of students were chronically absent in school year 2022-23, and a third of 9th graders missed more than 30 percent of school days.

Absenteeism is arguably the greatest impediment to recovery as it undermines the effectiveness of educational investments. When students are absent, they miss critical instructional time and other resources, hindering their academic and socio-emotional development.

D.C.’s public schools must prepare for a difficult fiscal future.

Increased reliance on temporary and supplementary funding sources, combined with growing demands on school budgets, create a complex and challenging financial future for D.C.’s public schools. Across the entire public school system, LEAs are collectively relying on an estimated $410 million in non-formula funds for school year 2023-24. To fully match these non-formula funds for school year 2024-25, formula-driven resources must increase by an estimated 15 percent. It is worth noting that this fiscal cliff is atypical, and caused by well-intended funds for supporting students during pandemic recovery—and not a result of historical overspending, for example.

Executing such an increase under the current fiscal picture would be a tremendously heavy lift. The city’s own revenue is projected to grow at 2.8 percent from fiscal year 2024 to fiscal year 2025. If formula-driven school funding were to grow at the same rate, it would generate an estimated $70 million in additional funding, or about one fifth of the non-formula funds schools are receiving during the 2023-24 school year.

Under this new fiscal reality, as federal aid expires and financial pressures intensify, LEAs must adopt new fiscal strategies to navigate challenges effectively. School leaders will not know the full extent of the resources they will have for school year 2024-25 until the District’s own fiscal year 2025 budget is adopted in June 2024. In the meantime, they can prepare for challenging times by preparing early and planning conservatively.

For LEAs facing cuts, it will be important to communicate changes in budgets with staff, families, and communities as early and as clearly as possible and seek feedback that can help leaders set priorities. Given the rapid expansion of staffing at schools in recent years, school leaders should adopt smart retention policies and plan ahead if staff reductions are going to be a part of their budget strategies. At the systems level, measuring the impact of different investments schools have undertaken since the beginning of the pandemic can help leaders identify and prioritize high-impact and high-value programs. School leaders can create a softer landing by using their remaining ESSER funds to meet future needs. Smaller single-site LEAs can contemplate resource sharing with other small LEAs that serve similar students or share a mission.

Introduction

Although COVID-19’s impact on the District’s residents and its economy was swift, the city’s finances did not immediately suffer. The District government, along with other state and local governments, received a substantial federal fiscal aid package for fiscal years 2020 through 2024, so the city could invest in programs necessary to support its residents through an extremely difficult period. In the case of the District of Columbia, this meant access to $4.7 billion in federal funds in addition to direct supports to residents and businesses.2 To put this in context, the annual local revenue for the city has averaged $9.2 billion between fiscal years 2020 and 2024. Spread over this five-year period, the federal fiscal aid was the equivalent of 10 percent of the District’s local revenue.

Additionally, years of conservative revenue estimates and lower-than-expected spending left the city with substantial end-of-year surpluses which resulted in growing reserves that were then used to balance future budgets. Consequently, between fiscal years 2019 and 2024, the District’s own revenue is projected to grow by 17 percent, but its operating expenditures are increasing twice as fast, at 34 percent.

D.C.’s public school budgets grew even faster. In fiscal year 2019, District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) and public charter schools collectively received $1.7 billion through the District’s budget. This amount was determined by the Universal Per Student Funding Formula (UPSFF), which has traditionally been the only locally funded budget source for public schools.3

By fiscal year 2024, the total budget allocated for public schools rose to at least $2.7 billion, with varying increases for DCPS and public charter local education agencies (LEAs). This marked a 56 percent increase from fiscal year 2019, while enrollment grew by about 9 percent during this period.4

About two-thirds of the growth in school budgets was driven by a substantial increase in resources schools have received through the UPSFF. The remaining one-third was the result of funds that DCPS and public charter schools received outside the formula. Starting in 2022, about 4 percent of school budgets have been financed by federal grants from the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER). Additionally, schools received other local resources outside the formula for purposes like budget stabilization, pandemic relief, and teacher salary increases. In fiscal year 2019, the contribution from such local non-formula sources was minimal. However, the share of non-formula local dollars increased to 8.2 percent in fiscal year 2023 and is projected to be 6.7 percent in fiscal year 2024.

The District of Columbia is now preparing to adopt its budget and financial plan for fiscal years 2025 through 2028. Fiscal year 2025 marks the first year since the pandemic’s onset when the District will not have any federal fiscal aid. The city faces added fiscal challenges such as weakening revenue projections, financial demands from the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) to fund public transit for the region, and other budget pressures. The financial plan indicates that to balance its projected budget with projected resources, the city’s total spending from local sources in fiscal year 2025 must remain the same as in fiscal year 2024.5 If applied equally across all agency budgets, this would imply zero growth for the locally funded portions of school budgets and an effective decline of 6 percent in school funding due to the loss of ESSER funds. This would be a significant shift from the recent trend of an average 9 percent annual increase in school budgets.

Teacher salaries add another layer of financial strain. In 2023, the District signed a collective bargaining agreement with the Washington Teachers’ Union (WTU), which includes DCPS teachers only. Although the agreement is new, it is backward looking and covers a four-year period between 2019 and 2023. Negotiated pay increases under the contract are expected to cost $92 million in fiscal year 2025 and $103 million in fiscal year 2026.6 Currently, these costs are covered largely by the Workforce Investment Fund, not the standard formula funding.7 Including these salary increases for DCPS and public charter schools in the funding formula cannot be accommodated in the current financial plan without cost-cutting elsewhere in the D.C. government.8

Moreover, these concerns do not account for any additional wage increases that might be negotiated for 2024 and beyond.

The financial outlook for schools could improve in coming years if local revenue increases rapidly, but the current picture is not particularly bright. In fiscal year 2025, the District’s local revenue is projected to increase by 2.8 percent,9 or $280 million. To put this number in context, in fiscal year 2024, schools are relying on an estimated $410 million in combined ESSER and non-formula funds.

The expiration of federal fiscal aid, combined with a weakening revenue picture and lackluster enrollment growth, points to a loss of significant resources and a potential fiscal cliff for the District’s public schools. The size of this cliff will vary across LEAs. LEAs that serve a large share of economically disadvantaged students, especially at earlier grades, will experience the biggest fiscal shocks. These LEAs received larger amounts of ESSER funds per-pupil and will therefore experience larger losses when ESSER funding expires. Given birth and cohort retention trends, schools that serve earlier grades are also least likely to make up for this loss through enrollment growth. LEAs that have spent a larger share of their ESSER funds on staff salaries will face particularly complex decisions. Finally, smaller, single-site LEAs will likely see bigger impacts on instructional programs.

This report examines the sources of growth in school budgets in D.C.’s public school budgets in the last five years, quantifies the amount of temporary funds in school budgets, and identifies indicators of future fiscal distress, including the acute needs that have not yet been fully met. It also describes the fiscal environment in which the District must operate in the coming years and provides recommendations on what schools could do to prepare for the upcoming leaner years.

What are the sources of growth in the District’s public school budgets?

Since fiscal year 2019, school budgets, on average, have grown by 9 percent each year. This rate is twice the combined average annual growth in enrollment (1.2 percent) and the consumer price index (3.2 percent). During this period, about two thirds of the growth in school budgets were the result of increases to the UPSFF. The rest was financed by a combination of local funding outside the formula and pandemic related federal fiscal aid.

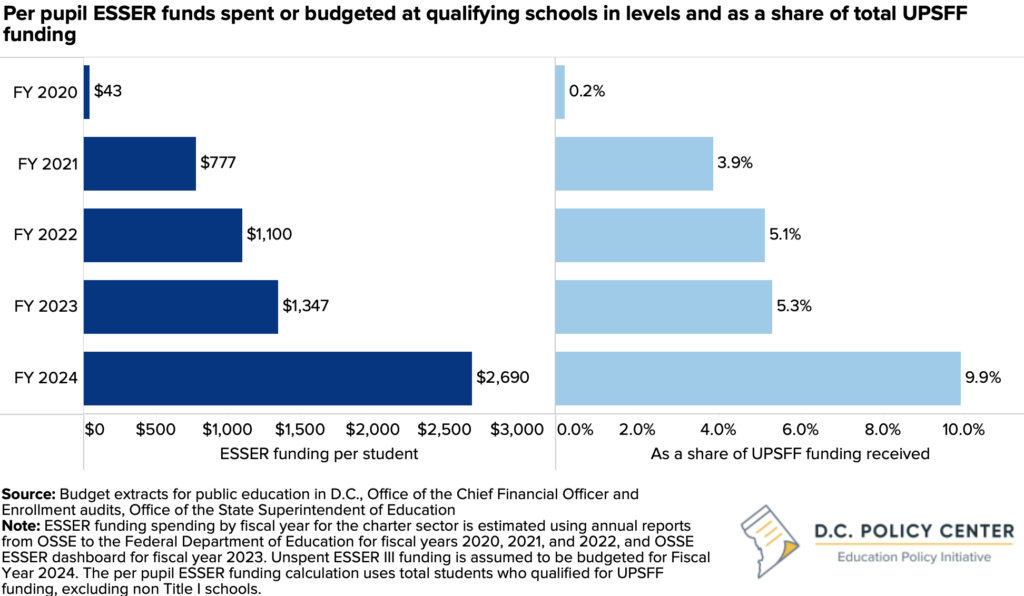

Prior to the pandemic, funding outside of the formula was rare. In fiscal year 2019, for example, non-formula local funds made up under 0.1 percent of total public school funding. In fiscal year 2023, this share was 8.2 percent, and fiscal year 2024, it was 6.7 percent. Additionally, beginning fiscal year 2020, most public schools began receiving federal grants known as ESSER funds. While ESSER funds were relatively small in fiscal years 2020 and 2021, starting fiscal year 2022, they have been accounting for over 6 percent of total school budgets.

How has public school funding grown in D.C.?

The primary funding mechanism for the District’s public schools is the UPSFF. The formula determines the budgets based on factors such as the number of students, their grade levels, and specific student characteristics. Formula funding is distributed at the LEA level, which refers to the entity that has administrative control over the schools. LEAs can have multiple schools (such as DCPS or KIPP DC PCS) or a single site with just one school (like 39 percent of public charter schools in school year 2021-22).

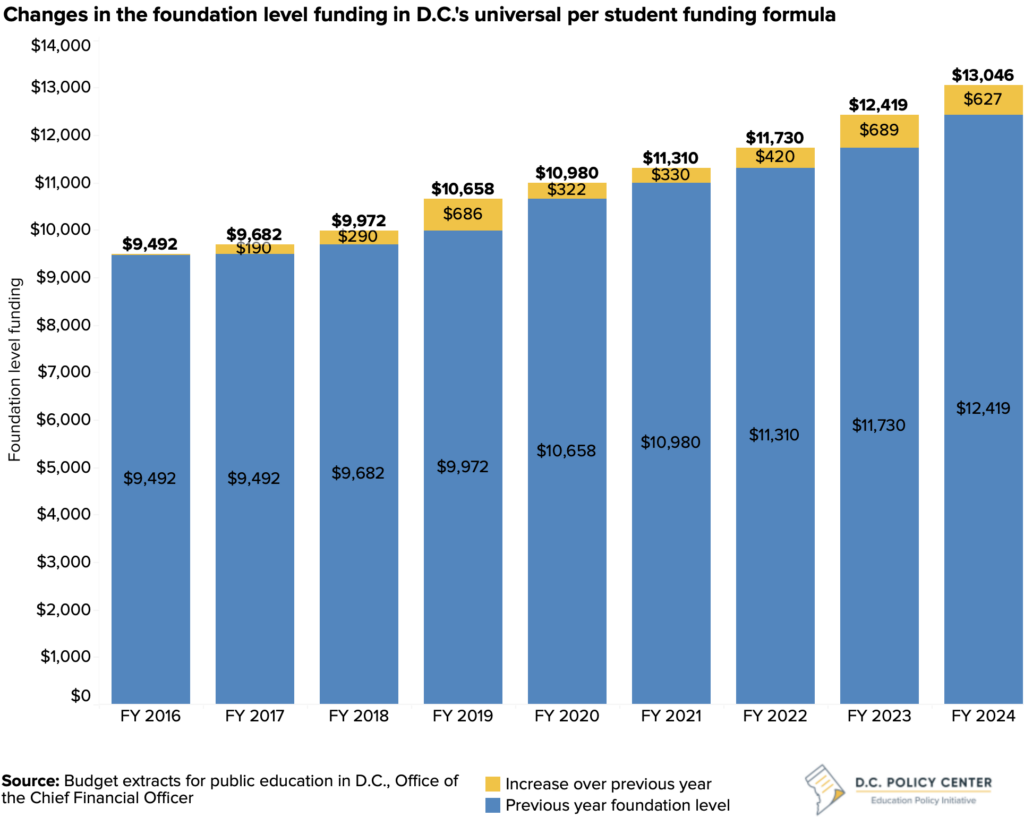

Each year, the city sets the foundation level funding, the base amount to which the city’s funding formula is applied.10 Schools receive base level funding for each student, with adjustments made for different student characteristics. For example, in fiscal year 2024, the foundation level funding was $13,046 per student. Schools received this amount for each student enrolled in grades 1 through 5, because students at these grade levels are assigned a formula weight of 1. However, for PK3 students, who are assigned a formula weight of 1.34, LEAs received $17,872.

In addition, schools receive more money for students who are considered at-risk,11 are English learners, or have disabilities. Schools with a high concentration of at-risk students also receive more funding through the formula via additional weights based on the school’s percentage of at-risk students.

Growth in UPSFF funds

Since the beginning of the pandemic through fiscal year 2024, school funding allocated through UPSFF increased by nearly $600 million. This is approximately 33 percent above formula-driven funding in the fiscal year 2019 budget.

About two thirds of the growth in formula funding has been driven by the increases the District made to the foundation-level funding. Since fiscal year 2019, the foundation level funding for UPSFF increased by 22 percent, with most of this growth happening in the last two years. In fiscal year 2020, the UPSFF foundational level increased by $322 per student, or 3 percent. In fiscal years 2023 and 2024, it grew by $689 and $627 respectively, or over 5 percent. These increases are on par with higher annual inflation in these years.

During the same period, average per-student funding that public schools received through the funding formula (after the application of weights) increased from $18,777 to $23,553 (average of the per student weighted funding), marking a 25 percent increase. The total per-pupil funding increased faster than the foundation level funding because of weight adjustments for at-risk students, an increase in the share of at-risk students, and other changes to weights.

Increases outside the funding formula

From fiscal years 2020 to 2024, D.C.’s public schools have received a new influx of at least $900 million from sources other than the standard funding formula. This extra money accounted for 7 percent of the total school funding during this period. Out of this amount, approximately $540 million came from federal ESSER grants. The remaining funds are from various local sources distributed outside the funding formula to address specific needs in public schools.

The proportion of spending from federal ESSER funds and local non-formula funds is higher for DCPS compared to charter schools. Between fiscal years 2020 and 2024, 10 percent of DCPS budget has been funded from these non-formula sources. For public charter schools, this share was 6.4 percent.

ESSER funds

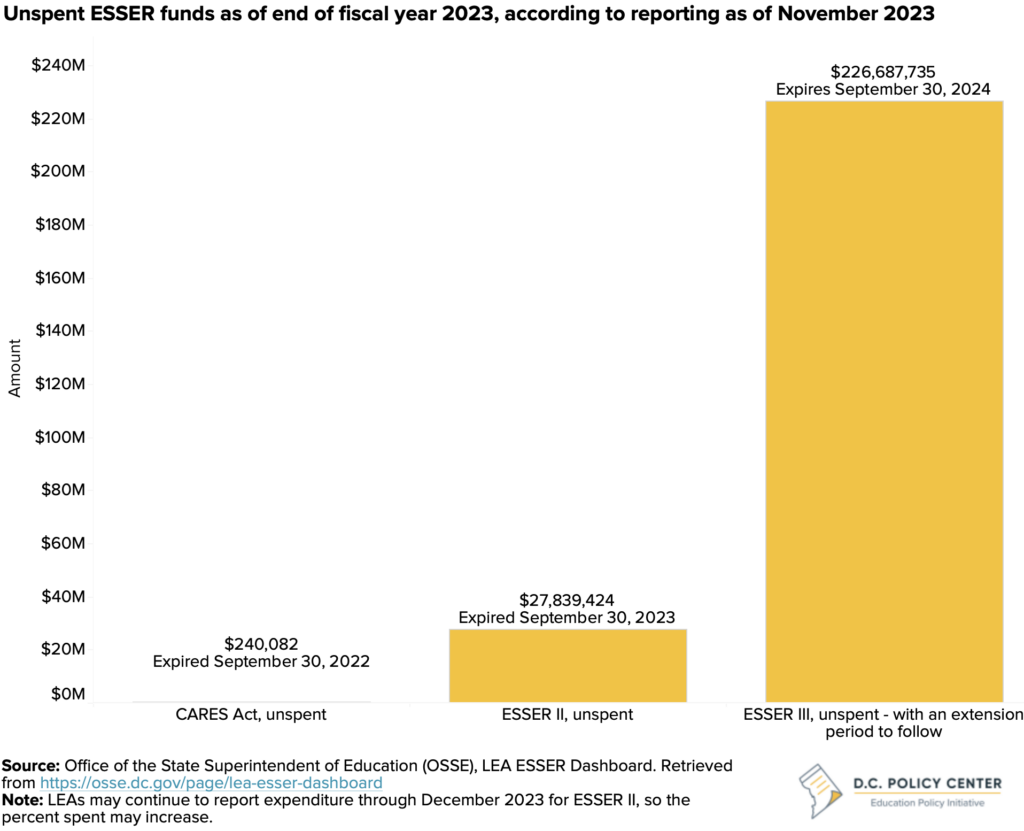

By the end of fiscal year 2023, 48 LEAs in D.C. designated as Title I schools (meaning at least 40 percent of their students are low-income), received and spent an estimated $286 million of ESSER funds.12 This averages to $1,134 per pupil each year between fiscal years 2020 and 2023 and is distributed over three rounds. This is a sizable amount—10 percent of foundation level funding, and 5.3 percent of all per-pupil funding schools received through the formula (after the incorporation of weights).

According to the spending data reported on OSSE’s LEA ESSER Dashboard, $226 million of ESSER III funds remain unspent across all eligible LEAs, which must be used or obligated by September 30, 2024.13 If LEAs spend all of the $226 million in school year 2023-24, they will effectively gain $2,690 per enrolled student. This amount is the equivalent of 20 percent of their foundational level funding and 9.9 percent of their total per-pupil funding for the 2023-24 school year, as calculated by the UPSFF.

ESSER spending

As a part of their Department of Educated mandated reporting, LEAs must provide a brief description of how their ESSER-supported programs and interventions respond to students’ academic, social, and emotional needs. An analysis of these brief descriptions identifies the following common themes:14

- Targeted interventions and tutoring: Many LEAs have implemented targeted tutoring and intervention programs focusing on reading and math skills to address learning gaps. These programs often involve small group or one-on-one instruction and use evidence-based methods to support students from underserved communities.

- Enhanced staffing: To reduce the student-to-teacher ratio and provide more personalized instruction, schools have hired additional staff members, including special education teachers, interventionists, and classroom aides.

- Professional development: Schools have invested in training teachers in various educational approaches, such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL), to better engage and support all learners, especially those from diverse backgrounds and with disabilities.

- Use of data: Schools also report an increased use of data-driven strategies to identify students who need support and to track the effectiveness of interventions.

- Social-emotional support: Schools have invested in social-emotional learning (SEL), counseling, and mental health resources.

- Curriculum enhancements: Schools report adoption of new curricula and educational materials, including computerized programs, to support skill development in key areas like reading (including investments in Science of Reading).

- Equity and access: Schools report investments that are accessible to all students, particularly those from historically underserved groups, such as racial and ethnic minorities, low-income families, and students with disabilities.

- Parental and community engagement: Some schools have offered training for parents to help support their children’s academic performance, aiming for community involvement in student success.

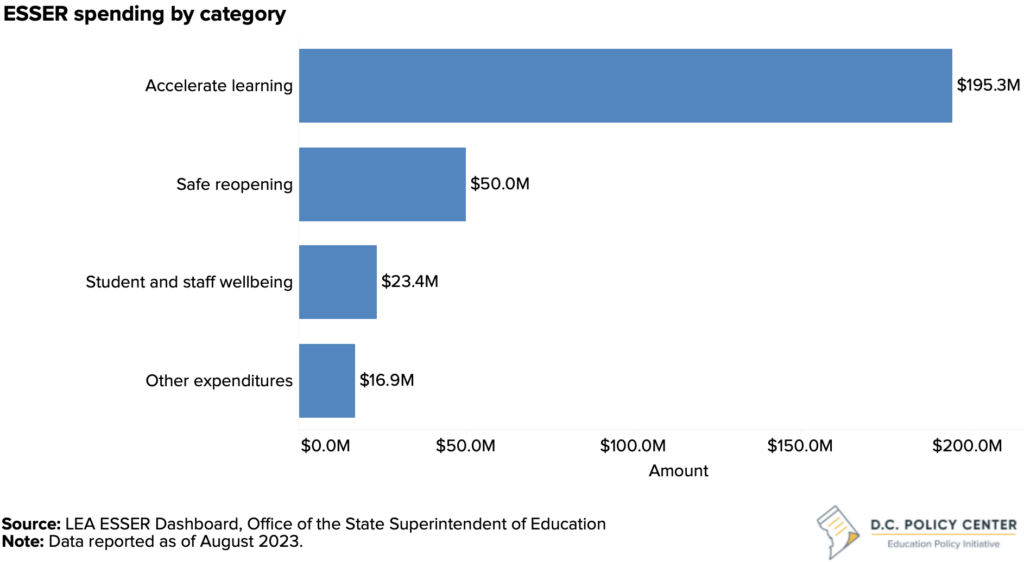

According to data from OSSE’s LEA ESSER Dashboard, by the end of fiscal year 2023, LEAs have reported investing $195 million of their ESSER funds in accelerated learning supporting in programs like high impact tutoring, summer programs, and teacher training.15 Another $50 million had been invested in safe school reopening, which includes building upgrades and the purchase of necessary supplies.

While schools often mention student and staff wellbeing as a priority, it has accounted for a relatively small share of total ESSER spending, representing 8 percent of reported spending. One probable reason for this smaller allocation is that schools received separate funding for school-based mental health both from the D.C. government and the federal government through a Department of Education grant.

DCPS, which has been awarded 56 percent of ESSER funds, has reported it allocated these funds both at the central level and directly to individual schools to address the academic, social, and emotional needs of students.16 According to data provided by DCPS, from fiscal year 2021 to fiscal year 2024, DCPS has allocated $21.2 million of its ESSER funds to schools. DCPS schools used ESSER funds to hire staff, purchase instructional resources and materials, and provide teacher materials and professional development aligned with a holistic approach to child development.

At the central level, DCPS has used ESSER funds to support various initiatives including citywide summer programming, teacher training, specific supports for English learner students and their families, high impact tutoring, special education, and support for the Science of Reading and Multi-Tiered Systems of Support.17

Additionally, since fiscal year 2021, DCPS has used $33.7 million of its ESSER funds to enhance safety measures and support operational activities. According to data shared by DCPS, it plans to invest another $19.2 million in the same area in fiscal year 2024.

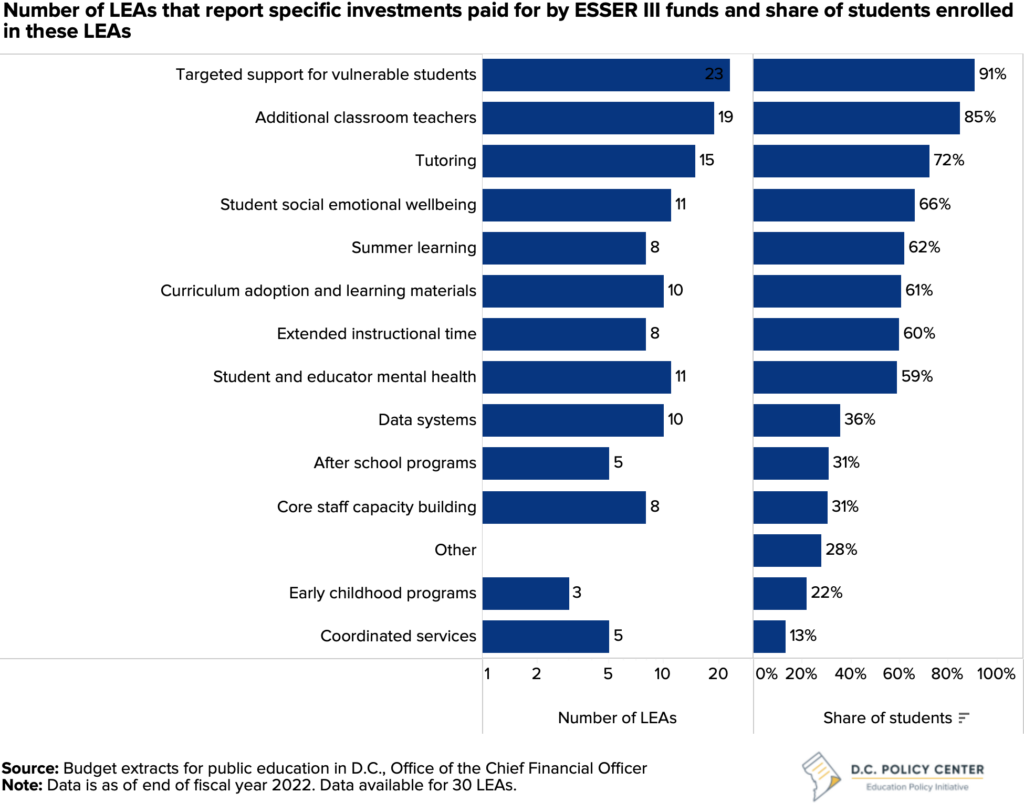

Out of the 48 LEAs that qualified for ESSER funds, 30 LEAs, collectively representing 30 percent of Title I school enrollment, have provided additional information on the specific type of program or activity in which they have invested their ESSER funding.18 These data show that the most common type of investments includes targeted supports for the most vulnerable students, which was mentioned by 23 LEAs. In addition, 19 LEAs reported hiring new staff, and 15 LEAs reported providing tutoring. Student social-emotional wellbeing, summer learning, investments in curricula and new data systems, and extended instructional time are also popular investments. In addition, 11 LEAs reported using their ESSER funding to create more flexibility in teacher schedules, possibly by hiring dedicated substitutes.

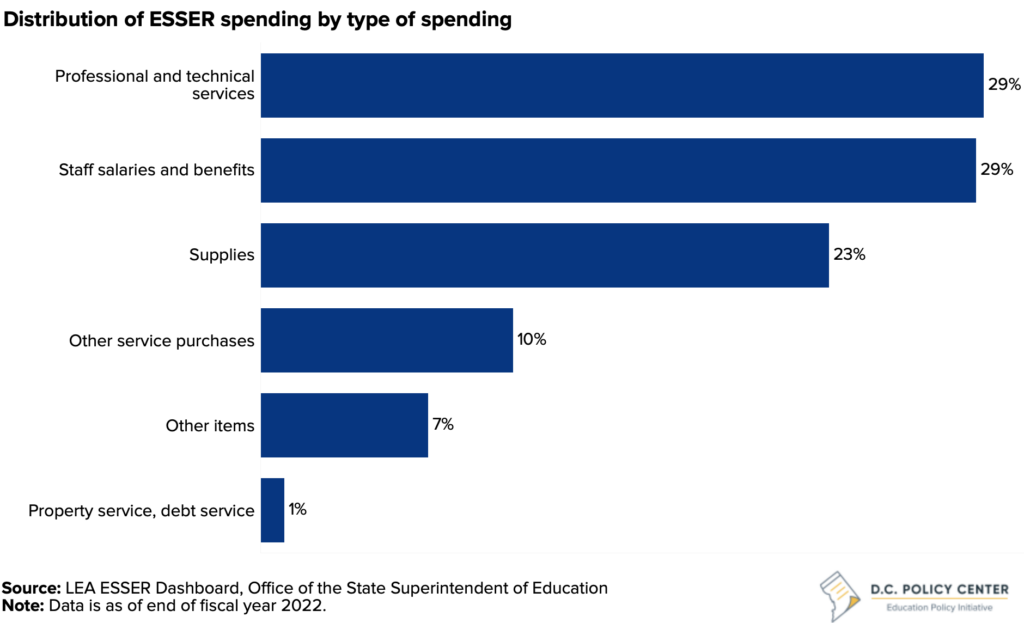

Data on the type of spending across the three ESSER rounds are available for fiscal years 2020 through 2022 only. These data show the most common use of ESSER funds included purchase of professional and technical services and spending on salaries and wages. Through fiscal year 2022, schools spent 29 percent of their ESSER funds in these two categories. Another significant area of expenditure was supplies, accounting for 23 percent of the total spending.

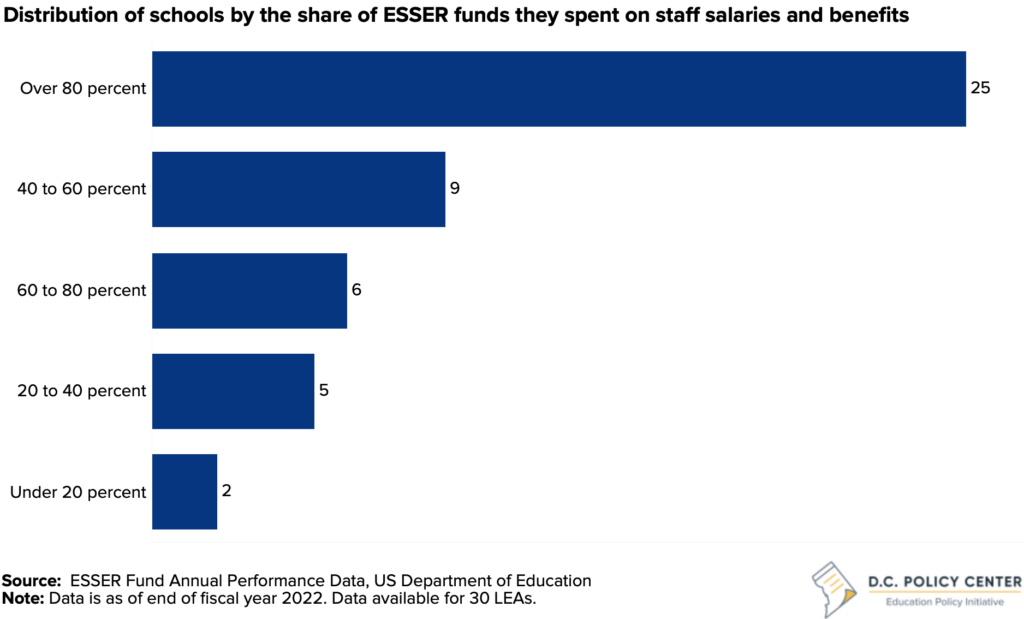

It is important to recognize that spending patterns can vary widely across LEAs. However, data show charter LEAs tended to spend a larger share of their ESSER funds on salaries and benefits—these personnel expenditures were 56 percent of all ESSER spending through fiscal year 2022. Out of the 47 charter LEAs, 18 reported spending more than 90 percent of their ESSER funds on salaries and benefits.

In contrast, DCPS spent a larger share of its ESSER spending on technical services and supplies. Through fiscal year 2022, DCPS had spent only 6 percent of its ESSER funds on personnel expenditures.

Schools have had varying success in spending their ESSER funds by the expiration dates. Most schools exhausted all of their ESSER I funds before the September 2022 spending deadline. Collectively, of the $37.8 million in ESSER I funds, 99 percent were spent by the deadline with only four LEAs not being able to spend all their money.

However, the situation was somewhat different for ESSER II. Schools collectively were approved for $155 million through the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSA) enacted in December 2020, with a spending deadline of September 30, 2023. According to publicly available data from OSSE’s LEA ESSER Dashboard, LEAs had collectively reported spending 127 million, or 82 percent of the allocated amount. Of the 48 LEAs that received funding in this round, 14 were not able to fully spend their ESSER funds, and four LEAs left more than 20 percent of their money unspent.

It is important to note that expenditure may increase: Available public data does not reflect final fiscal year 2023 expenditure totals, and some unspent ESSER II funds may be eligible for liquidation extension under U.S. Department of Education guidelines.

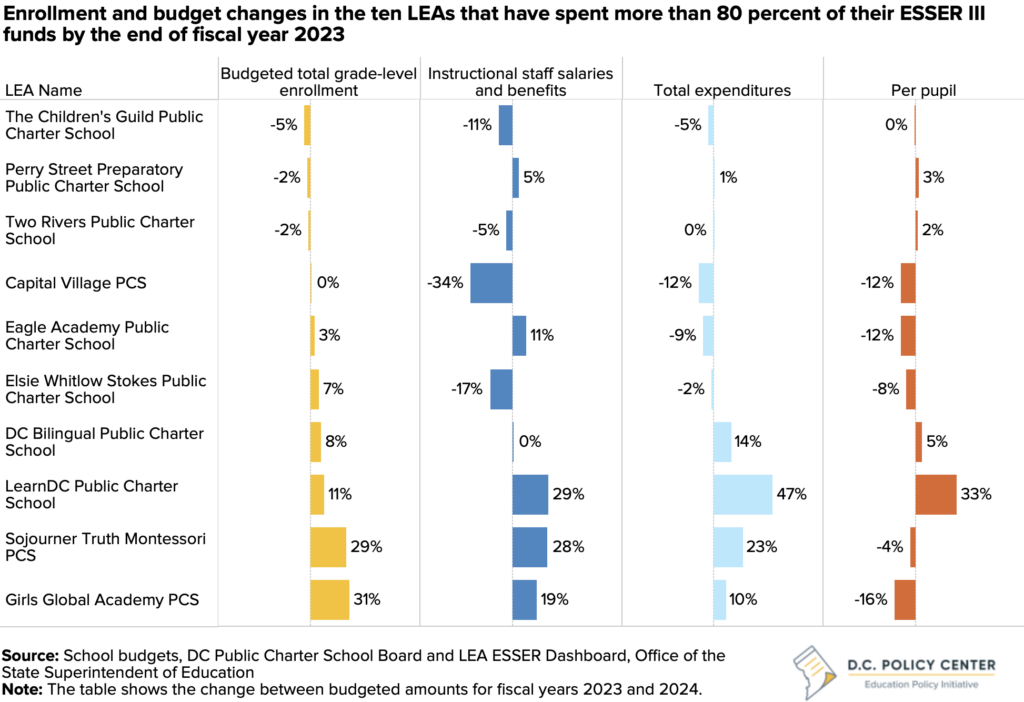

For ESSER III, the execution rate across all recipients was 34 percent by the end of fiscal year 2023 (with the same caveat that these figures could change). Fiscal year 2024 is the last year during which LEAs can use these dollars.19 Currently, 44 LEAs reported any type of ESSER III spending, and among those, 10 had already exhausted 80 percent or more of their ESSER funds and 6 depleted almost all.

For these LEAs, the fiscal cliff is already happening during the 2023-24 school year. An examination of fiscal year 2023 budgets (which include ESSER funds) in comparison to 2024 budgets (which do not include ESSER funds) for these ten LEAs reveals that, even though their collective enrollment is projected to increase by 5 percent in the 2023-24 school year, budgeted spending for staff has decreased by 1 percent and per pupil spending has dropped by 3 percent.

In contrast, seven LEAs, including DCPS, have reported spending less than 20 percent of their ESSER III funds. Again, these numbers could change when the OSSE LEA Dashboard is updated with full fiscal year 2023 spending. Without better strategies, these LEAs will most likely end fiscal year 2024 without exhausting all their funds.

ESSER and CARES equivalent funding for non-Title I schools

For the 20 non-Title I LEAs that were not eligible for ESSER funding, the District set aside approximately $10 million from a combination of different federal sources, mostly in fiscal years 2021 and 2022. This allocation is the equivalent of $866 per enrolled student over two years, roughly accounting for 3.7 percent of the foundation level formula.

Other local funding

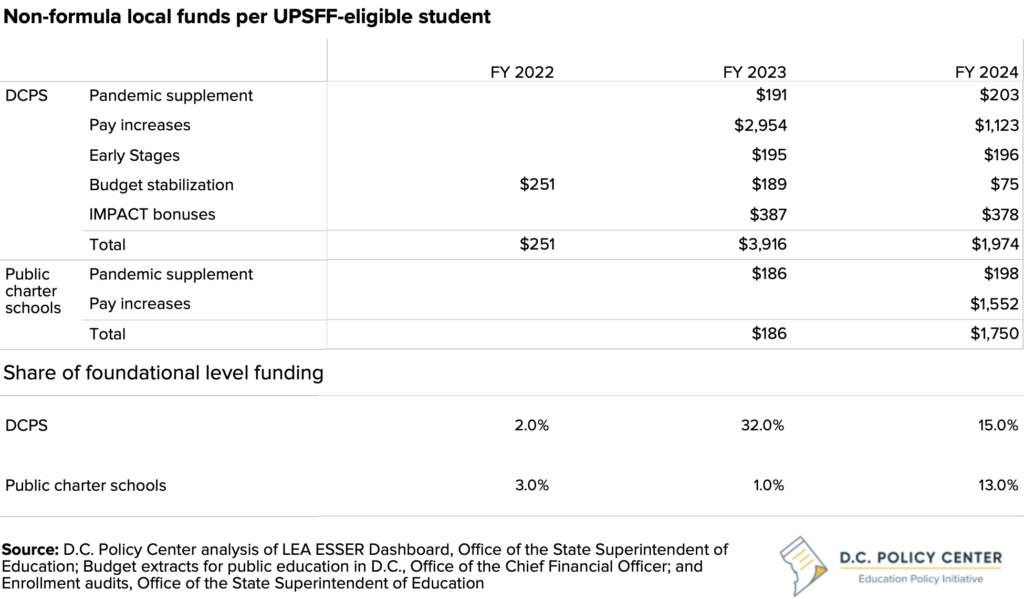

Since fiscal year 2022, D.C.’s public schools have been receiving an increasing amount of non-formula local dollars, a source rarely used in previous years outside of budget emergencies. In fiscal year 2022, the per pupil funding schools received from non-formula dollars was $251. In fiscal year 2023, this amount ballooned to nearly $4,000 for DCPS, and in fiscal year 2024, it was close to $2,000 for both DCPS and charter LEAs.

These non-formula local funds have been used to pay for the following:

- Pandemic Supplement: Both DCPS and public charter schools received $38 million through fiscal years 2023 and 2024 to help manage pandemic-related costs. On average, this provided about $196 per DCPS student and $192 per charter school student over the two years.

- Pay Increases: A new collective bargaining agreement in 2023 between DCPS and the Washington Teachers’ Union (WTU) covered a four-year period from 2019 to 2023, resulting in retroactive salary increases. Existing resources in DCPS’s budget were not sufficient to pay for the pay increases including the retroactive pay. In fiscal year 2023, DCPS received an $148 million outside the formula to meet the agreement’s requirements, including back pay. Another $57 million outside the formula was allocated for fiscal year 2024. For charter schools, the city approved a one-time, $73.5 million for fiscal year 2024, which can only be used to pay for salary increases. DCPS is set to receive another $195 million for salary increases during fiscal years 2025 and 2026, but no continued funding is specified for charter schools.

- Early Stages: DCPS receives funding to run Early Stages, a center that evaluates young children for developmental delays and disabilities for children intend to attend DCPS schools. The funding equates to $195 per student.

- Budget Stabilization: Additional local funds were allocated to ensure that no DCPS school’s budget decreases by more than 5 percent from the previous year. The total set aside for this purpose was $25 million, with the per-student impact varying yearly. A new legislation enacted in 2023 mandates that no DCPS school receives less funding than the previous year’s level unless enrollment declines to justify staff reductions.20 This aims to provide stability for individual schools but may prove to be challenging overtime if enrollment doesn’t grow while budgets remain inflexible.

- IMPACT Bonuses: DCPS received $38.8 million in impact bonuses over fiscal years 2023 and 2024, translating to approximately $380 per student.

In summary, these non-formula funds have been crucial in supporting schools’ operations, teacher salaries, and special programs, but they also represent a significant shift from the traditional funding mechanism.

Spotlight on DCPS21

DCPS, serving over half of D.C.’s public school students, is a critical case study in the potential budget pressures the District’s public education system may face when temporary funds are no longer available to LEAs. For DCPS, funds received through the traditional funding mechanism has increasingly become a smaller source of resources. Between fiscal years 2016 and 2021, formula funds made up 82 percent of resources set aside for DCPS (including the intra-district funds). In fiscal year 2024, UPSFF funds will account for 71 percent of DCPS’s funding.22 The rest is coming from a mix of sources that are often ad hoc and available for a limited time, including other local funds distributed outside the formula, federal grants and payments, private grants, and special revenue funds. DCPS is also expected to receive $352.8 million budgeted elsewhere and not included in DCPS’s official budget numbers. These resources include intra-district funds from other agencies’ budgets, from the Workforce Investment Fund and American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) resources for teacher pay increases per the WTU contract, and any unspent ESSER funds.

The heavy reliance on out-of-formula funds and federal fiscal aid will likely make fiscal year 2025 budgeting extremely difficult especially with the expiration of federal fiscal aid and the need to sustain teacher pay increases that are not accounted for in the city’s financial plan.

Indicators of future fiscal distress

The District’s public schools have been able to increase their spending at a rate faster than their enrollment has grown, primarily due to access to extra money received beyond the standard funding formula allocations. These additional resources sometimes paid for one-time needs, and other times for instructional programs and the hiring of additional staff. This means, once these funds run out, schools will face difficult decisions and may be forced to cut back on programs and staffing.

The fiscal cliff will be larger for some LEAs, and smaller for others. The LEAs that will face the greatest pressures are those who serve a larger share of economically disadvantaged students, especially at earlier grades. These LEAs not only received more ESSER funding on a per pupil basis but are also facing the poorest enrollment growth prospects. LEAs that have used a significant portion of their one-time funds, like the ESSER funds, for recurring expenditures, such as hiring new staff, will also see greater strain. Additionally, LEAs operating at a single location may face greater challenges, as they do not have the scale economies, especially for administrative functions from which larger, multiple-location LEAs benefit.

Enrollment pressures

Typically, school budgets are expected to grow in line with enrollment growth and the yearly increase in the foundation level funding. However, due to the availability of additional funding through ESSER and non-formula resources, school budgets grew much faster.

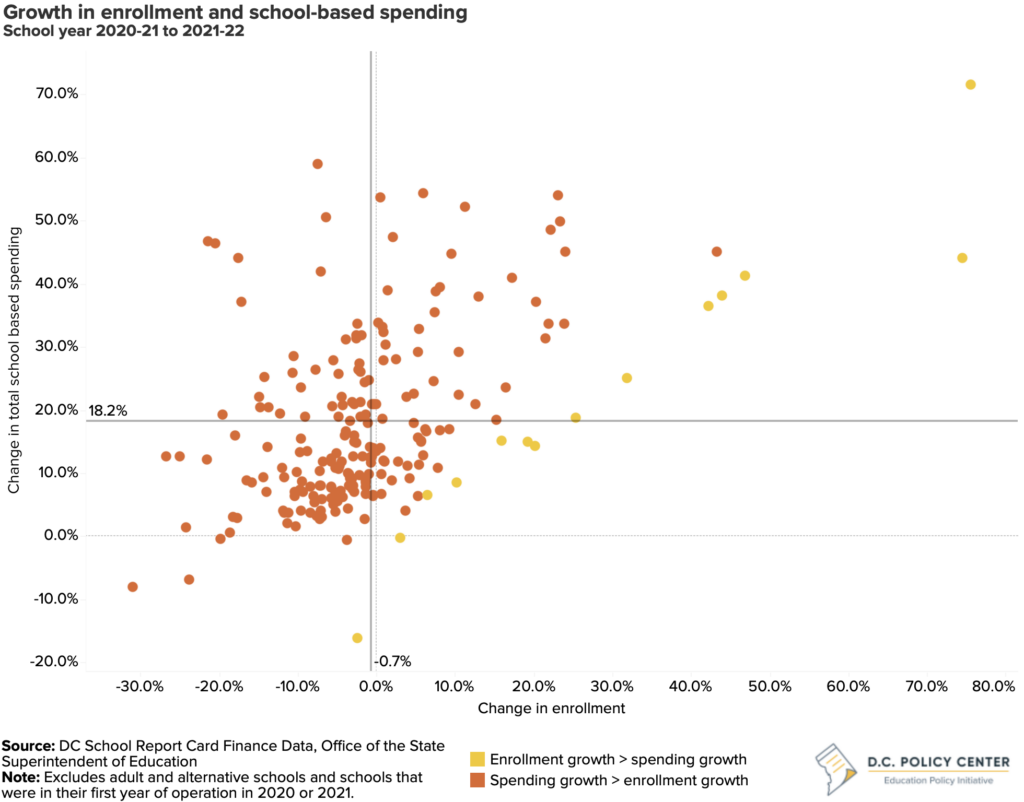

While the most recent school report card for school year 2022-23 does not provide financial data, a comparison of enrollment and finance data from the preceding two years reveals a noticeable pattern: many schools had fewer students but substantially higher spending. Between school year 2020-21 and 2021-22, on average, schools saw a 0.7 percent drop in enrollment but an 18.2 percent increase in spending. Specifically, 30 DCPS schools and 20 public charter schools across 13 LEAs experienced enrollment drops while their budgets increased beyond the growth in the base foundation formula for that year.

Trends for schools serving a high percentage of economically disadvantaged students

The financial challenges pose particular difficulties for schools that serve a high percentage of economically disadvantaged students, especially those in Wards 5, 7, and 8.

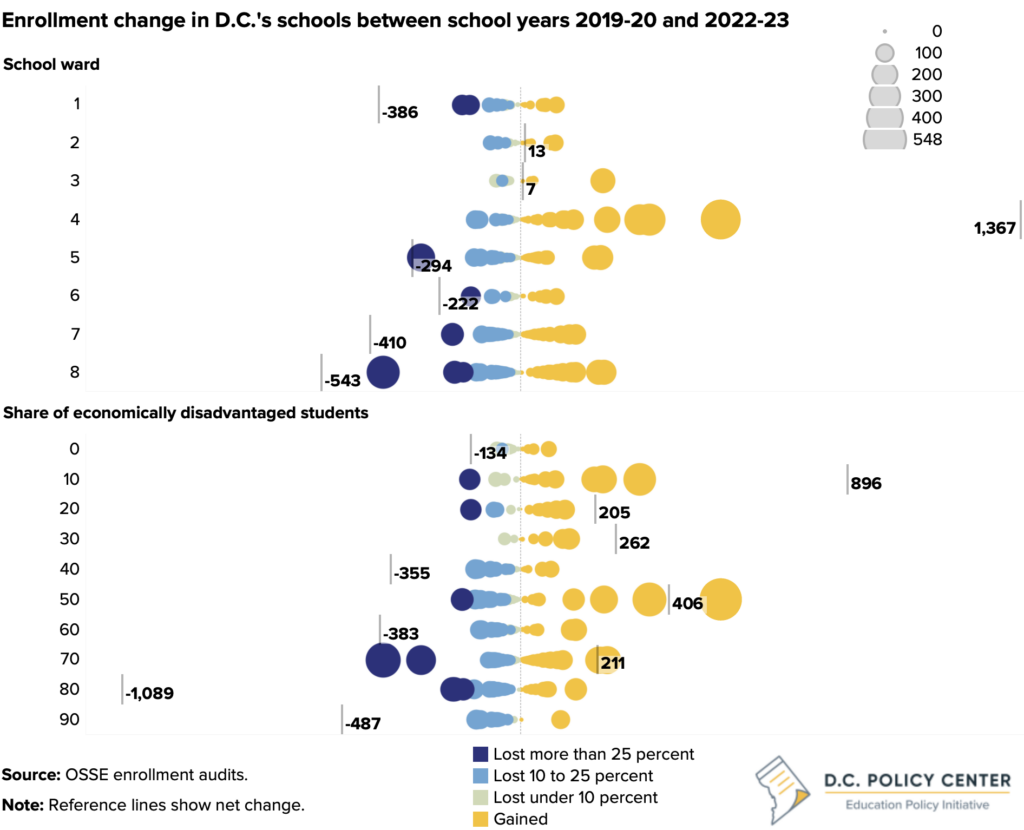

An examination of the 218 schools that were open in both school years 2019-20 and 2022-23, shows that 125 experienced a decrease in student numbers over these three years. Specifically, 75 schools saw their enrollment drop by at least 10 percent, and 24 schools lost at least a quarter of their students. Most of these schools with significant enrollment declines are in Wards 5, 7, and 8. Additionally, the schools facing the most significant drops in student numbers are also those serving a larger population of economically disadvantaged students. These schools are more likely to have received and spent more ESSER funds, making them more vulnerable to severe budget shortfalls as these temporary funds run out.

Trends by grade band

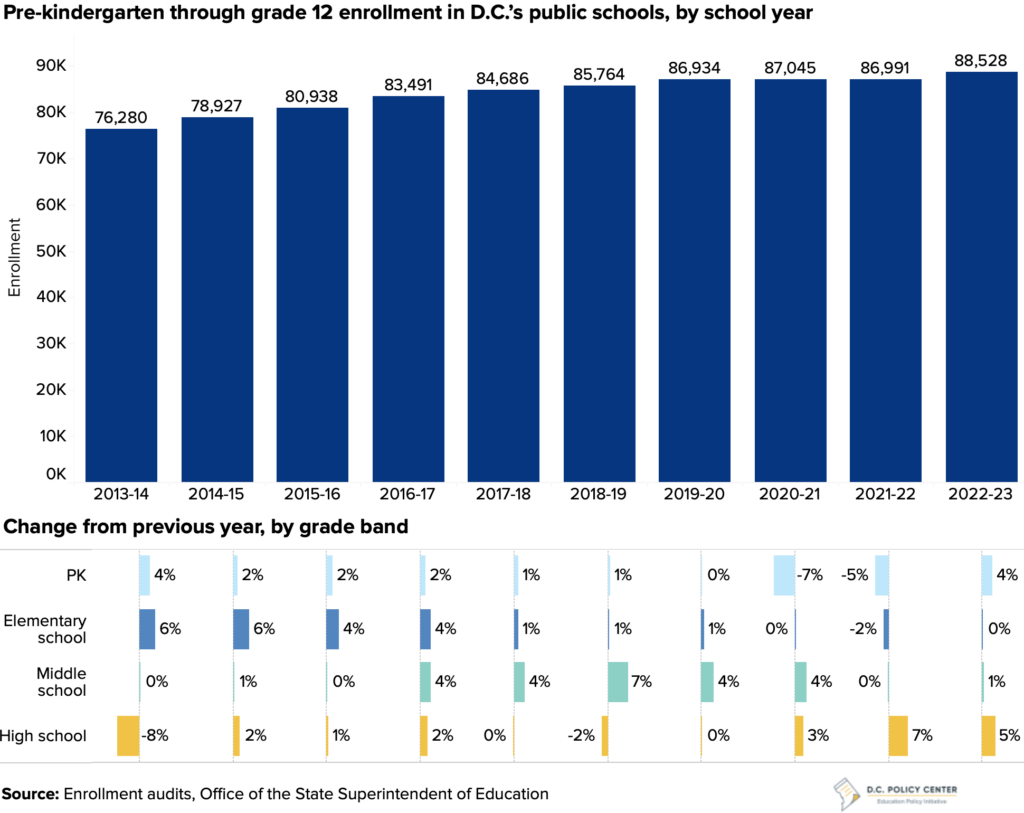

While some schools may hope that a rapid surge in student enrollment will generate sufficient funding to offset the loss of temporary funding, prevailing trends indicate this may not be the case.

Recent data show that after a two-year period of stagnation, the total enrollment across all schools saw a net increase of 1,537 students in the 2022-23 school year. However, this increase is mostly attributable to high schools, which added 840 students. Middle schools also saw an increase of 112 students. Compared to pre-pandemic levels in school year 2019-20, in contrast, elementary and pre-kindergarten schools actually experienced declines of 579 and 1,075 students, respectively.

The decrease in enrollment at earlier grades suggests that schools may continue to contend with lower enrollment in future years, as these smaller cohorts move to upper grades. That is, current reduction in enrollment that impacts the financial stability of schools serving earlier grades, may, over time, threaten the operational and financial strength of schools serving older grades.

Demographic shifts

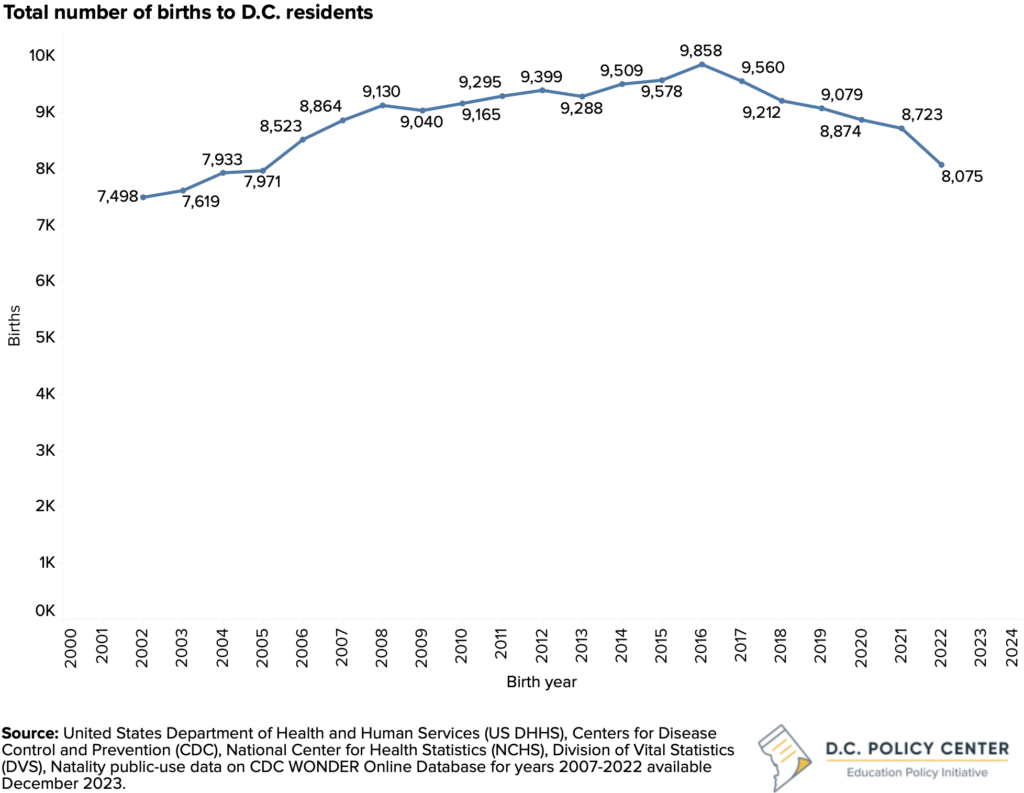

Related, births have declined: in 2022, there were 8,075 births in D.C., a low number not seen since 2005. This decline has been driven by both a decrease in fertility rates in the District and a shrinking population of women demographers characterize as childbearing age.23 24 The declining number of births in D.C. is a contributing factor to reduced enrollment in pre-kindergarten and elementary grades. The cohort of children eligible for pre-kindergarten in fall 2022 was smaller by 779 compared to the peak group in 2016.

Shifts in demand for D.C.’s public schools in kindergarten

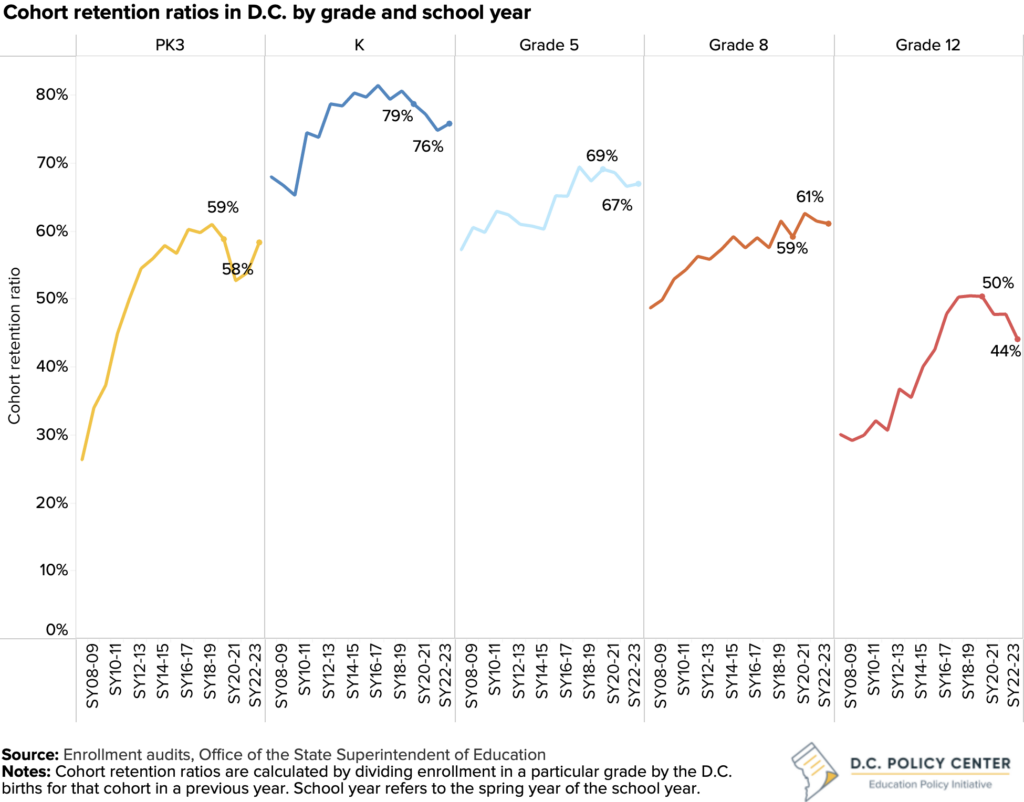

The level of interest in D.C.’s public schools also has an impact on enrollment, and data on the percentage of children born in D.C. who later enroll in its public schools show a declining trend. This metric, referred as the cohort retention ratio, is determined by comparing the number of students enrolled in a specific grade to the number of D.C. births for that age group.

Recent findings show that, except for 8th grade, cohort retention ratios have slightly decreased for most crucial transition grades compared to before the pandemic. Cohort retention, after experiencing a decline, has mostly recovered for pre-kindergarten in the last two years. Retention at kindergarten—the first mandatory school grade—shows a continued lower interest. The current retention ratio shows that enrollment is now at 76 percent, which is down from 79 percent before the pandemic.

Staffing pressures

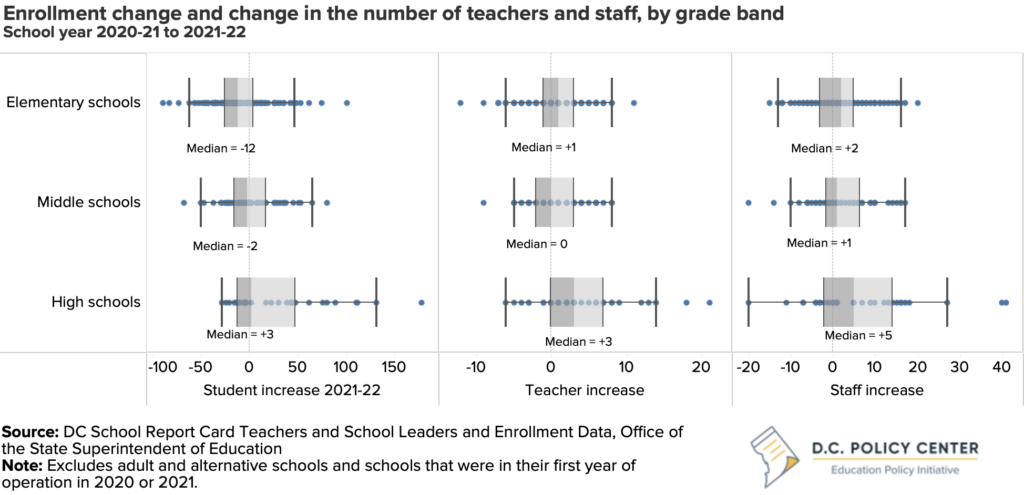

Many schools have used pandemic relief funds to hire more staff and teachers, even in cases when they experienced a drop in student numbers. Between school years 2020-21 and 2021-22, the average school saw a decline in enrollment and still added workforce. Specifically, at the elementary level, a typical school saw a decrease of 12 students but added two new staff members, including one teacher. In middle schools, despite losing an average of three students, they typically hired one more staff member. The average high school gained three students and expanded significantly by adding five new staff members, including three teachers.

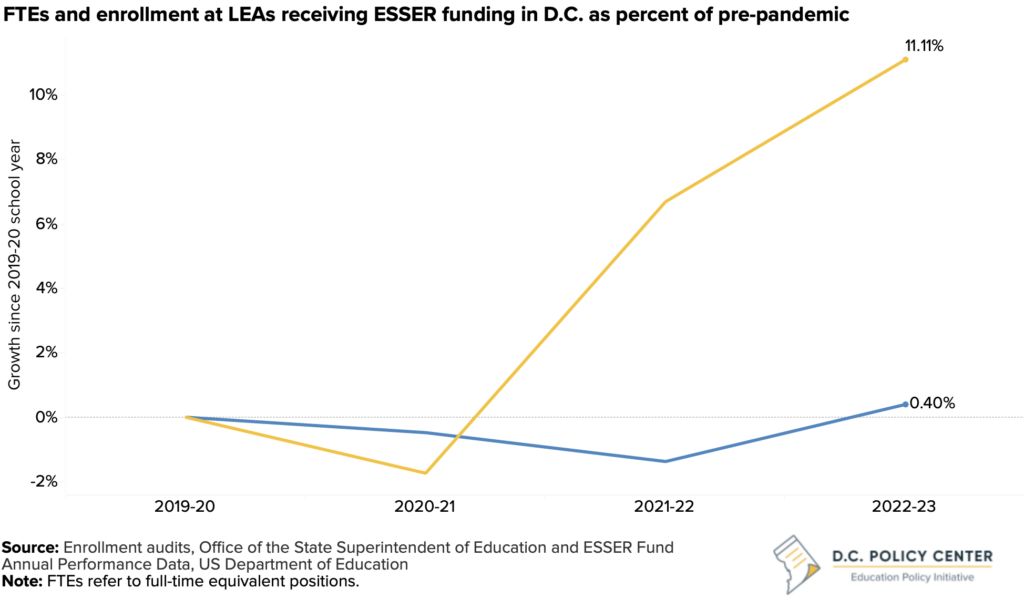

The gap between student enrollment increases and the expansion of school staff is especially pronounced among the 48 LEAs) that received ESSER funds. While these LEAs collectively saw a modest increase of 333 students (a 0.4 percent rise) from school years 2019-20 to 2022-23, their full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) surged by 1,631, marking an 11 percent increase.

Schools have reported using about 29 percent of their ESSER funds to hire new staff. However, this figure is skewed by the spending patterns of DCPS, which received more than half of the ESSER funds but used only 5 percent of its ESSER money for teacher salaries and benefits. Among the other 47 public charter LEAs for which data is available, 25 used over 80 percent of their ESSER funds for staff salaries and benefits, and 13 used all. These schools are likely to face significant challenges and potential disruptions to their teaching programs once the ESSER funding runs out—noting that with ESSER spending guidelines are flexible, it is possible that LEAs have preserved other resources for future needs.

Many of the acute problems produced by the pandemic are still present

The additional funding schools received between fiscal years 2020 and 2024 was intended to help them safely reopen schools and bring back their students, address the learning loss students experienced during the first two years of the pandemic, and meet the needs of their students and staff.

While recovery-related funds are expiring, the recovery is not complete.

Academic achievement

The most recent PARCC scores indicate that, at current rates of improvement, it will take multiple years to fully recover from disruptions caused by the pandemic, particularly for high school students.

School year 2022-23 marked a return to normalcy after continuous COVID-19 related disruptions. This year’s statewide assessment indicates achieving full recovery from these educational setbacks will be a lengthy process. The percentage of students meeting or exceeding standards in English Language Arts (ELA) and math showed a modest increase of 3 percentage points compared to the 2021-22 school year.25

These improvements are similar to the yearly academic growth rates students experienced before the pandemic implying a return to usual yearly improvements but not necessarily achievement levels. The share of students meeting or exceeding expectations has returned to the levels of nine years ago in math and five years ago in ELA.

A deeper dive into these numbers shows that elementary and middle school students have shown a stronger rebound with their ELA scores increased by 3.5 percentage points and their math scores by 3.4 percentage points. These rates of improvement for ELA are consistent with those seen before the pandemic, and the increase in math is surpassing the pre-pandemic annual growth.26 However, high school students have not demonstrated any improvement during this period in either subject.

Absenteeism

Chronic absenteeism is a persistent problem across D.C.’s public schools. While absenteeism was already high prior to the pandemic, it became an even bigger problem post-pandemic, partly due to changing attitudes towards the need to attend school. In D.C. Policy Center’s listening sessions, students and parents reveal that they are attributing less importance to in-person attendance in school. The increase in absenteeism poses a significant challenge because it undermines all the investments schools have made to improve academic and socio-emotional outcomes for students.

Despite a decrease in chronic absenteeism to 43.7 percent in school year 2022-23 from 48.1 percent in school year 2021-22,27 the rate remains exceptionally high. It is also higher than pre-pandemic levels; in school year 2018-19, 29.4 percent of students were chronically absent.28

One must exercise caution when comparing this number to the most recent chronic absenteeism rate. The District recently changed its absenteeism policies, allowing students to miss a longer part of the school day before being counted as absent. That is, students who miss more time in school, and would have been marked as absent under the old rules, may be counted in attendance under the new rules.

This issue is particularly severe in high schools, where 60 percent of students are chronically absent, surpassing rates in other grade bands. Alarmingly, almost a third of 9th graders start high school with “profound” chronic absenteeism, missing 30 percent or more of school days.29 This is particularly troubling because research has shown that 9th grade is a critical time for setting the stage for students’ future academic success, timely graduation, and post-secondary success.30

Fiscal year 2025 and beyond

In fiscal year 2024, the D.C. government is planning to use $166 million in federal fiscal aid to balance its budget. In addition, the city plans to tap into $756 million in other one-time sources of funding to support a spending level that is lower than the fiscal year 2023 level.

Given this financial landscape, the discontinuation of the federal fiscal aid beginning fiscal year 2025 could have profound fiscal ramifications for both the D.C. government and D.C.’s public schools. The city’s current financial plan indicates that, for the fiscal year 2025, it will need $615 million in one-time funds just to maintain the same level of spending as in 2024. This trend of relying heavily on one-time funds continues into future years in the financial plan, with recurring revenue never reaching a point high enough to pay for recurring expenditures. While using one-time funds can be a temporary solution to fiscal distress, especially when the city has a lot of money in its reserves (as has been the case for D.C.), it cannot continue forever.

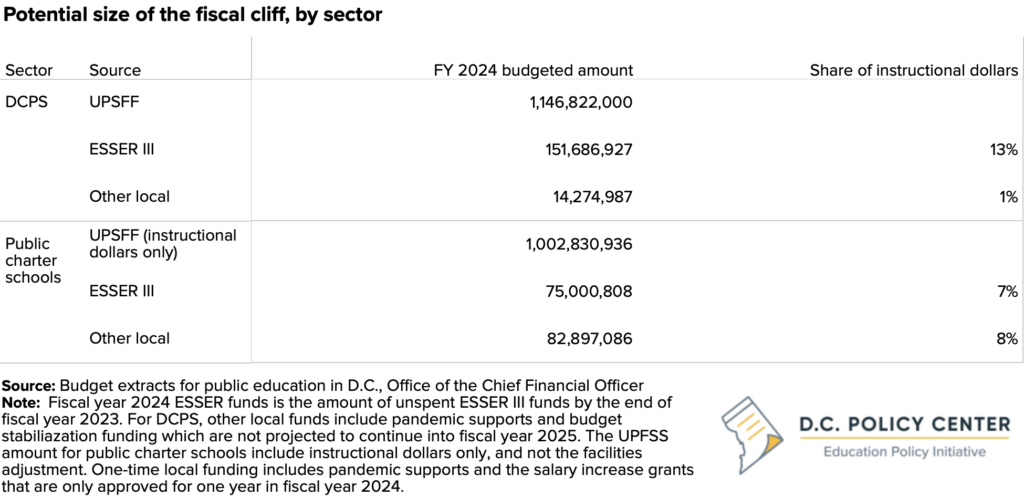

What is the size of the fiscal cliff?

The current financial plan does not foresee a reduction in the local fund budget soon. Beginning fiscal year 2025, public schools would still see a decline, simply due to the loss of ESSER funds. For DCPS, this is the equivalent of about 13 percent of the UPSFF funding in 2024. This is a best estimate of the size of the fiscal cliff for DCPS schools. Other local money that is likely to not continue (stabilization and pandemic relief funds) add another 1 percent to the gap. The cliff could be much deeper if some of the money DCPS receives from other agencies is also paid for by federal fiscal aid.31

For charter schools, the ESSER III funds that remain to be spent in the 2024 fiscal year amount to about 7 percent of their instructional UPSFF funding. While this percentage is smaller than that of DCPS, it only represents half of the fiscal cliff that public charter schools are expected to face. In fiscal year 2024, public charter schools will also receive a significant amount of one-time local funds from D.C. government grants aimed at increasing teacher salaries. If these funds are fully utilized, they will add an additional 8 percent to the fiscal cliff, totaling a 15 percent reduction in instructional funds in school year 2024-25. Additionally, charter schools can only access these funds if they use them for salary increases. While this may provide temporary financial relief today, it will amplify fiscal distress in the coming years.

City-level factors that could influence fiscal year 2025 budget

Beyond economic conditions, several factors will influence the budget situation for D.C. in the 2025 fiscal year, which could either improve or deteriorate given the current financial outlook. These factors include:

- Fiscal year 2023 audit. The District’s Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for fiscal year 2023 was released on February 1, 2024.32 This report shows that while the city ended the fiscal year with a surplus of $419 million, the city’s financial position weakened compared to fiscal year 2022. At the end of Fiscal Year 2022, the District had enough surplus to replenish all the required reserves to meet the goal of having 60 days’ worth of cash in hand, and still had an extra $440 million, which was then used to fund future year budgets. All of the fiscal year 2023 end-of-year surplus would be needed to replenish the required reserves, and even then, the District would still be short $312 million to reach the 60-day goal.33 This means the city will begin the fiscal year 2025 budgeting process without the benefit of extra cash left from the previous year.

- Baseline budget. The Office of the Chief Financial Officer (OCFO) starts the budgeting process by releasing a Current Services Funding Level budget. This Current Services Funding Level budget deducts one-time expenses from the current year’s approved budget, adds back one-time reductions, and adjusts for unavoidable costs like inflation and contractual commitments. This document estimates the funds needed to support the same level of services in the next year, excluding one-time programs. This document is crucial not only for planning but also for identifying the extent of one-time expenditures that lack future financing.

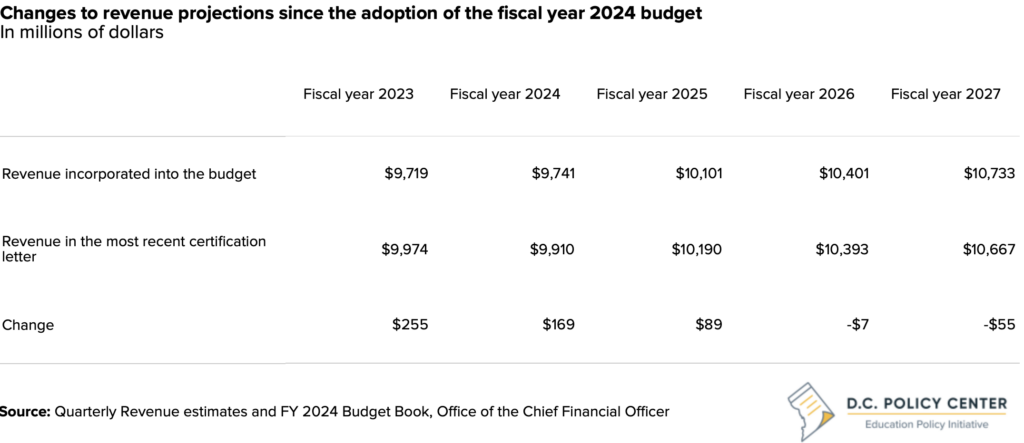

- Revenue projections. The District’s Chief Financial Officer regularly updates revenue forecasts in February, June, September, and December each year. Since the last budget approval, three updates have collectively increased the projected revenue for the 2023-2027 period by $450 million. The upcoming forecast in February 2024 will lay the foundation for the next budget. If these projections stay the same, the city could allocate the additional revenue for fiscal year 2025 and beyond. However, the revenue increase isn’t spread evenly over years, which limits how much can be used for ongoing costs like the UPSFF.

- WMATA funding. The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) is facing its own significant financial challenges and fiscal cliff. It may require up to $750 million as early as June 2024. It is expected that D.C., along with other jurisdictions in the WMATA compact, will share this cost. However, the exact amount D.C. needs to contribute and how it will finance this contribution are currently unclear.

- Advocacy pressures. Just as one-time budget allocations for D.C. public schools are under pressure, similarly funded programs across other government sectors are also at risk of being cut. There will likely be increased advocacy efforts to continue these programs. However, in times of limited resources, the government will face tough choices about which programs to sustain and which to stop.

School and LEA-level strategies

With a deteriorating fiscal picture, D.C.’s public schools will have to adopt new strategies to ensure their limited budgets are used as effectively as possible. This is a new chapter for D.C.’s public schools, which have long been accustomed to growing budgets. Schools have several tools they can employ to temper the impacts of the pending fiscal cliff.

Budget very conservatively for Fiscal Year 2025 and communicate to staff and families early and clearly.

LEAs are now planning their fiscal year 2025 budgets. However, they will not have a complete understanding of the available resources until the District’s own fiscal year 2025 budget and financial plan is approved. This will not happen until June 2024. In the interim, LEAs should adopt a cautious approach and identify potential cost-cutting measures.

It is crucial for LEA leaders to proactively communicate with staff and families about any potential changes in their budgets for the 2024-25 school year as well as any potential program and staff cuts. Typically, staff and families do not know what resources an LEA uses to pay for a program or a teacher, and whether these resources are permanent or temporary. LEA leaders should take the initiative to clearly articulate the changing financial conditions and potential impacts on school budgets and staffing.

Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab34 suggests framing these communications around the amount of ESSER funding per pupil, showing which programs were supported by these funds, and explaining whether schools will maintain, modify, reduce, or eliminate these programs or staff. Additionally, changes in enrollment and expected variations in funding levels for schools experiencing a decline in enrollment should be explained during these communications. LEA leaders should also be open to community feedback as they make these difficult decisions.

Collaborate to measure impact.

Largely using ESSER and one-time funding, LEAs made significant investment in many new programs to help support recovery and student wellbeing. These include tutoring, school-based mental health supports, hiring of attendance coordinators, and other programs. While these programs have been popular, their effectiveness, especially in the D.C. context, has not yet been explored.

School leaders should consider learning from each other on what interventions had more promising outcomes in academic growth, student wellbeing and attendance. District education agencies such as OSSE can be particularly helpful in this area by providing research, guidance, and city-level assessments of new and understudied interventions.

With more information about the outcomes of ESSER-funded investments, LEAs should think more systematically about the tradeoffs including which high-impact activities should be continued using annually recurring federal or local sources, and which to discontinue.

Prioritize ESSER spending today to address future needs.

LEAs have the option to use their current ESSER funds for investments that will decrease their future financial needs. This can include spending on planned capital improvements, building maintenance, buying supplies and instructional materials, or other planned infrastructure projects. By doing so, LEAs can free up more funds for instructional purposes in the future.

Additionally, if LEAs have their spending plans ready by the September 30 deadline, this strategy offers the benefit of extending the use of ESSER funds over a longer period. While ESSER funds cannot be allocated for staff salaries after September 30, 2024, they can be committed (through service or purchase contracts) by that date and then spent over the following 18 months.35

LEAs are encouraged to submit plans that focus on evidence-based learning acceleration strategies, especially increasing attendance, providing high-quality tutoring, and increasing access to extended learning time.36 37

Prioritize ESSER spending today to stretch UPSFF funds into the future for a softer landing.

In addition to paying for future needs, LEAs can use their ESSER funds for current spending that they originally planned to pay for using their local resources. The guidelines for using ESSER funds are flexible. LEAs facing difficulties in using these funds for recovery can instead apply them to other, justifiable operational costs, thus preserving their resources, like UPSFF dollars, for future needs. This approach is particularly useful for public charter schools, which can save unspent funds for later use, if LEAs are afforded flexibility in amending their ESSER spending plans.

While this approach can buy some time for adjustments by increasing reserves that can be used for future needs, it is only temporary. Charter LEAs would still have to right-size their budgets to account for a post-ESSER fiscal reality.

Unlike charter schools, DCPS must return unspent funds back to the city’s coffers. However, the city could help by establishing a reserve to retain any DCPS surplus at the end of the 2024 fiscal year, allowing these funds to be used the following year.

Adopt smart retention policies.

In the last few years there has been substantial focus on hiring and retaining teachers in the District of Columbia. While retention suffered, D.C.’s public schools hired new staff even when their enrollment was not growing. This was especially common among the LEAs eligible for ESSER funds. From school year 2019-20 to school year 2022-23, enrollment at these LEAs grew by 333 students, which amounts to a mere 0.4 percent, but their full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) surged by 1,631, or by 11 percent.

LEAs, especially charter LEAs could continue hiring new staff in fiscal year 2024, as collectively they are eligible to receive $73.5 million which they can only use for teacher salaries, recruitment, and retention. But this is a one-time commitment, and charter LEAs that hire new teachers using this funding this year may have to drop these positions or make cuts elsewhere in fiscal year 2025.

Considering the pending fiscal challenges, school leaders may have to change course and prepare for staff reductions for fiscal year 2025. This shift in approach necessitates moving from a focus on hiring new teachers and retaining existing staff to a deeper understanding of what aspects are worth safeguarding. Staffing policies can have multiple objectives, such as improving supports for high need students or increasing diversity among staff. However, with reduced funding, schools will have to set clear priorities.

Careful and early planning can help school leaders in setting these priorities well in advance, ensuring greater transparency, and gathering input from staff, parents, and the community. Early planning also offers schools a more diverse set of strategies than last-minute actions, such as a “last in, first out” strategy. This proactive approach can help schools avoid undesirable outcomes such as furloughs, pay reductions, spending freezes, or relying on attrition to manage staff levels.

Consider resource sharing.

Larger LEAs with multiple schools can spread overhead costs over more students and centralize some services when it is more cost effective. However, this type of economies of scale is not available for smaller, single-location LEAs.38

With a tightening fiscal picture, smaller LEAs should consider sharing resources with other small LEAs that have similar needs, serve similar students, and pursue similar missions. Resource sharing across LEAs can include consolidating administrative operations to optimize operational dollars, colocation to reduce rent or lease payments, and staff sharing to lower personnel expenditures.

Conclusion

The District’s public education system is entering a phase of significant fiscal transformation and challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly altered the District’s financial landscape, with substantial federal aid temporarily bolstering the city’s and schools’ budgets. The federal aid is expiring in fiscal year 2025, and given flat local revenues, it is unlikely that the District can make up for this loss using its own revenue. Many of D.C. public schools are facing a looming fiscal cliff. The potential decline in funding is expected to affect staffing levels, educational programs, and the overall ability of schools to meet the diverse needs of their students.

This situation is particularly acute for schools serving economically disadvantaged students, especially in the earlier grades, where the reliance on additional funding has been more pronounced. For these schools, the prospect of making up for some of the losses through enrollment growth is particularly dim, as key indicators such as number of births and cohort retention point to low or no enrollment growth.

Schools and LEAs in the District must now strategize to adapt to these financial constraints. This includes prudent budgeting for fiscal year 2025, effective communication with staff and families about potential changes, and collaboration to assess the impact of various programs funded by temporary sources. Schools must prioritize the use of their remaining ESSER funds to address future needs and stretch their budgets as far as possible. Additionally, adopting smart retention policies and considering resource sharing, especially among smaller LEAs, will be critical in navigating through these financially constrained times.

The District’s ability to manage these financial challenges effectively will have lasting implications on the quality of education and the equitable provision of educational services. As such, it calls for a collective effort from all stakeholders–including school leaders, teachers, families, and policymakers–to ensure that the quality of education in the District of Columbia is sustained and continues to improve, even in the face of financial adversity.

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared with generous support from Education Forward DC, the Walton Family Foundation, and the Kimsey Foundation. The authors are grateful for the review and comments from Andrew Eisenlohr, Nora Gordon, Derrick Mashore, Phyllis Jordan, and Will Stoetzer. The authors are also grateful to the Office of the Chief Financial Officer, District of Columbia Public Schools, the DC Charter School Alliance, and the Office of the State Superintendent of Education for the data they shared as well as the observations they offered. Their review in no way indicates an endorsement of this report, and all errors are the responsibility of the D.C. Policy Center authors.

We are so appreciative as well of the panelists who discussed these findings at our release event, including Danielle Branson (OSSE), Paris Saunders (OCFO), Pat Brantley (Friendship Public Charter School), and Betty Chang (ERS).

Appendix A. Key sources of data about schools and public finance in D.C.

The D.C. Policy Center is grateful to present and analyze publicly available data and data requested from the following key sources for this report.

Budget extracts for public education in D.C. (OCFO)

- The OCFO publishes annual budget and financial plan books that include information on actual past expenditures and approved budgets. The D.C. Policy Center was grateful to request and receive the data behind these tables for spending on public education generally and District of Columbia Public Schools in more detail. The data included actuals through fiscal year 2022 and approved budgets for fiscal year 2023 and 2024, with information as available by funding source, program title, activity title, and service description.

DC School Report Card (OSSE)

- First published for school year 2017-18, the OSSE DC School Report Card presents key school-based information for all of D.C.’s public schools. The report cards provide an overall rating and more than 150 data points to communicate how a school is doing with all of its students, in addition to information about the school itself. This report uses publicly available information from these datasets: Aggregate Enrollment, Teachers and School Leaders, Assessment, Finance, and Attendance.

ESSER Fund Annual Performance Data (US Department of Education)

- The US Department of Education requires all ESSER grantees to report on ESSER funds received under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act; CRRSA; and ARPA. Grantees must submit an annual report describing how the state and subrecipients used the awarded funds during the performance period. Annual Performance Report Data is published on an annual basis following the completion of each fund’s respective annual data collection period. These data were publicly available for fiscal years 2020 and 2021. The D.C. Policy Center was grateful to request and receive from OSSE a preview of the data for the fiscal year 2022 submission.

LEA ESSER Dashboard (OSSE)

- OSSE’s LEA ESSER dashboard depicts the 90 percent of ESSER funds granted by OSSE to D.C.’s LEAs via formula grants. The dashboard shows data by LEA, four funding categories, and the three rounds of ESSER grants. The expenditure data in this dashboard and spreadsheet is updated quarterly and based on reimbursement requests submitted by LEAs to OSSE. This report references the data available as of November 2023. These data are publicly available.

Public charter school budgets (DC Public Charter School Board)

- The DC Public Charter School Board publishes LEA budgets with budgeted enrollment, revenues, expenses, and cash flows for each public charter LEA presented in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). This information is publicly available.

Endnotes

- The employee count includes full-time equivalents, or FTEs.

- This analysis is based on data from https://www.covidmoneytracker.org. For details, see the Appendix.

- Schools also receive private grants, and occasionally emergency funding when facing budget pressures, but these are small. In addition, schools receive federal funds and grants. In addition, DCPS has benefited from other local services such as facilities maintenance and contributions towards teachers’ retirement, but it did not have any control over these funds.

- This number is different from what could be calculated using the approved budget funds because of the change in budgeting practices. In 2023 and 2024, DCPS budgets, for example, no longer showed intra-districted funds at DCPS. To make year-to-year comparisons valid, we added onto the DCPS budget these intra-districted funds using information DCPS releases for intra-districted grants that exceed $10 million.

- The total approved expenditures in the local portion of the District’s budget is $10.69 billion in fiscal year 2024, and projected to grow by only $4 million—virtually a rounding error—in fiscal year 2025.

- This information is from the fiscal impact statement prepared by the Office of Revenue Analysis on the Compensation and Working Conditions Agreement between the District of Columbia Public Schools and the Washington Teachers’ Union, Local #6 of the American Federation of Teachers Approval Resolution of 2023. Available at: http://app.cfo.dc.gov/services/fiscal_impact/pdf/spring09/FIS%20DCPS%20WTU%20Compensation%20Agreement%20Approval%20Resolution%20of%202023.pdf

- Of this, in fiscal year 2025, DCPS will receive $66 million from the Workforce Investment Fund. This is the equivalent of $1,287 per enrolled student in school year 2023-24.

- Similarly, public charter schools received one-time funds for teacher salary increases in fiscal 2024, but this support is not expected to extend into fiscal 2025. Approved in the Fiscal Year 2024 budget and authorized under Subtitle (IV)(G) – Public Charter School Teacher Compensation Amendment Act of 2023 of the Fiscal Year 2024 Budget Support Act of 2023.

- D.C. OCFO December 2023 revenue certification letter published on December 29, 2023. Available at https://cfo.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ocfo/publication/attachments/Dec%202023%20Revenue%20Estimate%20Letter_12%2029%202023_FINAL.pdf

- This is codified in the D.C.’s Official Code, and can only be changed by legislation.

- Students are defined as at-risk if they qualify for public benefits (Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, TANF, or Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, SNAP), experience homelessness, are involved in the foster care system, or are overage in high school.

- OSSE LEA ESSER Dashboard, available at https://osse.dc.gov/page/lea-esser-dashboard. Data retrieved on January 28, 2024.

- These numbers are preliminary. According to OSSE, the current reporting in the ESSER dashboard may not reflect the full amount of spending in fiscal year 2023. If LEAS report additional spending for that fiscal year, the numbers for fiscal year 2023 will increase, and if some of this is for ESSER III funds, the numbers for fiscal year 2024 could decrease.

- Fiscal year 2022 USED Annual ESSER Reporting, received from OSSE.

- These numbers could change if schools report additional fiscal year 2023 spending.

- Data from USED Annual ESSER Reporting available at https://covid-relief-data.ed.gov/profile/state/DC for fiscal year 2020 and 2021. Fiscal year 2022 report was received from OSSE.

- Data shared by DCPS on the actual and planned use of ESSER funds.

- This information is available for ESSER III only. Fiscal Year 2022 USED Annual ESSER Reporting, received from OSSE.

- Recent guidance from the US Department of Education has allowed schools the same type if liquidation extension as was available under ESSER II. Further, LEAs will have an additional 18-month liquidation period so long as they can obligate this spending by September 30, 2024. The extension cannot be used for salaries and wages. Additional information is available at the US Department of Education website, https://oese.ed.gov/files/2024/01/ARP-Liquidation-Extension-Letter-1.9.24-final-for-signature-v3.pdf

- B24-0570 - Schools First in Budgeting Amendment Act of 2021 D.C Act 24-0785, DC Law 24-0300. Effective from Mar 10, 2023.

- Sayin, Y. 2023. “Loss of pandemic-related resources will test DCPS’s budgeting practices.” D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/dcps-fiscal-headwinds/

- This differs from the approved budget data as it includes intra-district funds for DCPS which are no longer shown in the budget books as a part of DCPS budget. We include them in this analyses to ensure that we can compare across years.

- Coffin, C. and Rubin, J. 2022. Declining births and lower demand: Charting the future of public school enrollment in D.C. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/enrollment-decline/

- And 2023 births could even be lower. Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which provides this data, hasn’t released the birth numbers for 2023 yet, the most recent estimates from the Census Bureau indicate there were approximately 7,627 births between July 1, 2022, and June 30, 2023. For details, see Burge, D. (2023) The most recent population numbers in three charts. Available at https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/population-in-three-charts-2023/

- Coffin, C. 2023. “Chart of the week: New PARCC data show overall gain for DC students last year—but high school progress remained flat.” D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/parcc-data-gains/

- Coffin, C. 2023. “Chart of the week: New PARCC data show overall gain for DC students last year—but high school progress remained flat.” D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/parcc-data-gains/

- Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). (2023, November 30). DC School Report Card – Attendance. Retrieved from https://schoolreportcard.dc.gov/state/report/explore/102

- Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). 2022. DC School Report Card Data. Retrieved from https://osse.dc.gov/dcschoolreportcard

- Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). (2023, November 30). District of Columbia – Attendance Report 2022-23 School Year. Retrieved from https://osse.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/osse/publication/attachments/2022-23%20Attendance%20Report_FINAL_0.pdf

- Easton, J, Johnson, E, & Sartain, L. (2017, September). The Predictive Power of Ninth Grade GPA. Retrieved from https://consortium.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/2018-10/Predictive%20Power%20of%20Ninth-Grade-Sept%202017-Consortium.pdf

- Alternatively, the cliff could be smaller if DCPS cannot spend the substantial amounts of ESSER III funds it has not yet spend. This, hopefully, will not happen given how flexible federal rules are for spending ESSER money.

- District of Columbia Government (2024), FY 2023 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report, available at https://cfo.dc.gov/node/1704691.

- The cash in hand is the equivalent of 51 days of working capital. For details see Testimony of Glen Lee, Chief Financial Officer, at the Public Briefing on the Fiscal Year 2023 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report before the Committee of the Whole, delivered on February 1, 2024. Available at https://cfo.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ocfo/release_content/attachments/Public%20Hearing%20on%20the%20FY%202023%20Annual%20Comprehensive%20Finanical%20Report.pdf

- Edunomics Lab. 2024. “2024: A Big Year For Ed Finance.” Edunomics Lab. Retrieved from https://edunomicslab.org/

- Previously, the deadline for committing funds for future use was 120 days, but the U.S. Department of Education has recently extended this period to 18 months, provided LEAs have established spending plans.

- For more information, please see U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education September 18 2023 Letter to Grantees and U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education January 9 2024 Letter to Grantees.

- LEAs would have to request these extensions through OSSE. The letter describing the terms for granting these extensions can he found here. https://www.aasa.org/docs/default-source/advocacy/USED-ARP-ESSER-Response-Letter

- D.C. Policy Center’s analyses of spending data at the LEA level shows that there is a strong negative correlation between school size and per-pupil spending across D.C.’s public schools. For example, in school year 2021-22, multicampus schools spent $1,100 less on a per-pupil basis compared to single-site schools. This gap remains at a sizable $700 when one excludes DCPS.