Mayor Bowser’s recently-announced budget includes $3.8 million for additional student supports through school-based mental health programs. The announcement of this investment comes at a critical time as students, teachers, and families struggle with the impacts of COVID-19 and its associated mental health challenges. While schools invested in supports like hiring additional staff and providing social-emotional integration trainings during the 2020-21 school year, many students and families reported challenges when trying to access mental health resources.

It is difficult to know from system-level data whether the mental health services that are offered to students and families are sufficient to their needs and what barriers students may face when trying to gain access to mental health supports.

In this latest installment in our D.C. Voices series, we hear directly from students, researchers, and administrators to learn more about the barriers students may face when accessing services and how available mental health services currently meet needs.

Related reading

- State of D.C. Schools, 2020-21 (full report)

- D.C. Voices: Mental health supports during school closures

- Challenges outside of school for D.C.’s students and families during the pandemic

Mayor Bowser’s recently-announced budget includes $3.8 million for additional student supports through school-based mental health programs. The announcement of this investment comes at a critical time as students, teachers, and families struggle with the impacts of COVID-19 and its associated mental health challenges.

A year of virtual learning last year during the COVID-19 pandemic introduced and exacerbated issues for students’ mental health, as summarized in State of D.C. Schools, 2020-21.1 In the 2020-21 D.C. State Board of Education (SBOE) Report of the Student Advisory Committee, mental health was identified as a major concern for students due to loneliness, family issues, heightened anxiety, technology troubles, excessive workload.2 The report suggested that mental health issues contributed to lower levels of class participation, engagement, and overall productivity.

Local education agencies (LEAs) invested in additional mental health supports last school year. In the summer of 2020, teachers and staff at 16 of 55 LEAs (which collectively enroll 69 percent of students) received additional training on how to integrate social-emotional learning practices into their curriculum.3 Many LEAs also planned to hire additional staff, engage with external mental health organizations, embed wellness checks within daily lessons, or assign a wellness coach to each student. In addition, LEAs implemented systems to identify students who need additional support and refer them to in-house practitioners or third-party counselors. Schools connected with counselors from community-based organizations or the Department of Behavioral Health (DBH). However, even during this current school year, 2021-22, LEAs continued to work to fill counselor positions. As of March 2022, 20 schools had vacancies for their DBH clinicians and 69 had vacancies for clinicians from community-based organizations.4

While LEAs offered a variety of different supports, students and families reported challenges when accessing services and a mixed level of awareness of what supports are available to them. In D.C. Policy Center focus groups, high school students shared that it was challenging during school year 2020-21 to get to know a counselor through a virtual platform and that it was difficult to find a private space at home to participate in counseling.5 Parents in focus groups shared that they found it challenging to navigate the referral process through their children’s schools – this led some parents to seek help from private providers. In a PAVE end-of-school year survey from 2021, 54 percent of parents answered “yes” when asked whether their children’s school had access to a mental health professional/clinician; 41 percent of those surveyed replied that they weren’t sure.6

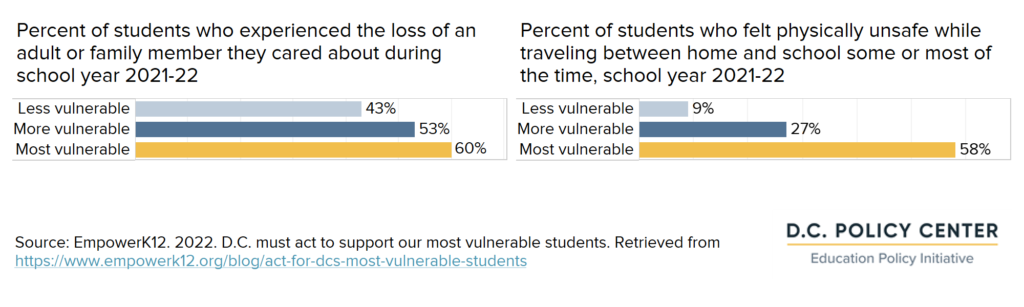

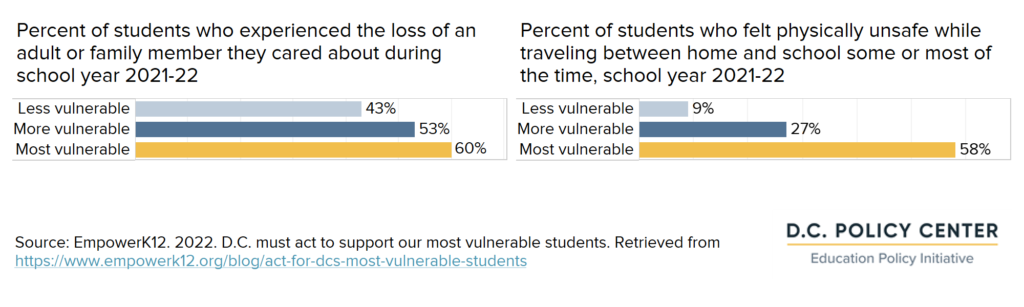

While some of students’ mental health concerns may have been helped by a return to in-person learning in school year 2021-22, many students have continued to struggle. A recent survey released by EmpowerK12 suggests that the most vulnerable students—classified as those who may be experiencing food insecurity, feel they live in an unsafe neighborhood, or have home situations that are not stable— have lower overall levels of wellbeing than their peers. Sixty percent of the surveyed students designated as most vulnerable reported that they had experienced the loss of an adult or family member they care about since the start of the school year, compared to 43 percent of those students designated as less vulnerable. Of the most vulnerable students surveyed, 58 percent said that they felt physically unsafe while traveling between home and school either most or some days, compared to just nine percent of less vulnerable students.7 Both of these sources of stress may have negative impacts on mental health, and affect students’ mental capacity to engage with school.8

It is difficult to know from system-level data whether the mental health services that are offered to students and families are sufficient to their needs and what barriers students may face when trying to gain access to mental health supports. To find out more, the D.C. Policy Center reached out to students, researchers, and administrators to ask how the available mental health services currently meet needs.

Mikalei Miller, Senior, Thurgood Marshall Academy Public Charter High School

I think things can improve if the mental health providers speak up more and encourage students to come to them when they have mental struggles.

At my school, I am aware that there are a few counselors and therapists that are available for students. I do not think these services meet the needs of my peers because there is a mixed awareness about these services. I have had many mental health challenges but I received support from outside sources, and I improved my mental health by taking a day or two off from school. Personally, I did not seek help from my school because I did not know about any school-based therapists. I also did not feel comfortable approaching any school staff. I think things can improve if the mental health providers speak up more and encourage students to come to them when they have mental struggles. Many students suffer with issues like anxiety which make them hesitant and uncomfortable to reach out to school-based mental health providers. Implementing mental health days and reminding students of school-based support is a great way to approach this issue.

Department of Behavioral Health and Office of the State Superintendent of Education

OSSE and DBH are expanding technical assistance opportunities for schools to strengthen crisis prevention and intervention and schools’ ability to address and respond to root causes of educator stress. These timely and targeted investments will help schools meet acute student mental health needs exacerbated during the pandemic, as well as support school communities as they move from recovery to restoration.

Over the past four years, Mayor Muriel Bowser has made a significant investment in ensuring there are adequate mental health services in all District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) and public charter schools. Using a public health approach, the District makes a range of behavioral health services available to every child through prevention, early intervention and treatment. Schools start the year by using the school data and stakeholder input to complete a school strengthening tool and create a work plan. School mental health teams use this information to create a work plan that addresses the mental health needs of the school community. Although the mental health support needs of the students continue to unfold during this process of recovery and restoration, the current school-based behavioral health services are aligned to address grief and loss/trauma; violence prevention/emotional regulation and problem-solving; suicide prevention; and substance use disorder (SUD) prevention and treatment. Schools are also using the input from students and parents to develop programming around specific concerns that they have. One specific example comes from a DCPS middle school where the mental health team worked together during the pandemic and distance learning to develop presentations on mental health topics for the entire seventh-grade class. Students enjoyed the presentations and requested that the team continue to present on various topics. The students contributed their ideas to topics they wanted to be discussed. The mental health team expanded the presentation to all grade levels, have continued the presentations when returning to in-person learning and divided the months among the whole team.

DBH and providers from community-based organizations are active members on their school’s mental health team and are creatively engaged in strategies to promote awareness of school-based behavioral health providers and their services and support youth and families in being comfortable talking about behavioral health. School teams remain engaged in strategies to reduce stigma and increase the promotion of available services. One example of creative ways to promote and engage was done by the DBH clinician at a DCPS middle school. The clinician placed signs around the building asking if anyone was “feeling stressed, overwhelmed or having a hard time coping.” At the bottom of the sign was a tear-off with a QR code that linked to the counseling page explaining how to get in contact with the counseling team.

In furthering Mayor Bowser’s investment in school-based mental health, the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) works as a supportive and collaborative partner with DBH. Recognizing that school is often a place where youth mental and behavioral health needs are addressed, OSSE seeks to equip all schools with strategies to help address student mental health and wellbeing. These tools and resources include written guidance to assist local education agencies (LEAs) in developing and adopting policies and procedures for handling aspects of student mental and behavioral health, professional development for educators and school behavioral health staff, and curriculum and implementation resources to support schools with delivering education, prevention, and intervention services.

Given the known impact of the pandemic on youth mental health on top of an already troubling landscape of trauma and suicidal ideation among District young people, OSSE has utilized federal stimulus funding to deepen investments in trauma-informed approaches to care and suicide prevention education. Staff training and student curriculum are available at the elementary, middle and high school level and support schools with building a positive school culture that allows every member of the school community to thrive. OSSE and DBH are expanding technical assistance opportunities for schools to strengthen crisis prevention and intervention and schools’ ability to address and respond to root causes of educator stress. These timely and targeted investments will help schools meet acute student mental health needs exacerbated during the pandemic, as well as support school communities as they move from recovery to restoration.

Schools are already witnessing the impact of these investments. One public charter middle school reported that delivering the suicide prevention curriculum this school year not only helped educate students and staff about depression and suicide risk but also helped school staff identify nearly 40 high-risk students with a previously unreported suicide attempt, connect them to services and strengthen their connection to trusted adults. A DCPS middle school team shared how they integrated the curriculum into the health class and used the OSSE training to help prime the health teacher to facilitate discussions with students and to promote help-seeking behavior. And, a school behavioral health provider at a charter elementary school described students engaging in bibliotherapy with social emotional books such as, “My Friend is Sad,” by Mo Willems and “Sometimes I’m a Pillow,” by Susan Lovett, LICSW.

“The scholars loved the book and they understood that everyone has different feelings and different emotions at different times. Our instructors incorporated [the curriculum] into their Morning Meetings to remind and continually teach scholars that we all have feelings and emotions every day. Sometimes the emotions can be happy and positive as well as not as being sad. We always want our scholars to know that we will develop with them a creative way to help them utilize their words when dealing with an emotional need.”

These critical conversations normalize talking about mental health in safe, non-judgmental ways. While barriers to mental health care remain present in the lives of the District’s youth and their families, the coordinated and collaborative efforts put forth by DBH and OSSE seek to reduce these barriers and present youth and families with multiple pathways to access appropriate and timely care.

District families may continue to rely on the Access HelpLine, 1(888) 7WE-HELP or 1(888)793-4357, as the easiest way for families to get connected to services provided by DBH and its certified behavioral health care providers. The Access HelpLine can also activate mobile crisis services and support families with getting connected to services available at their child’s school. Families are also encouraged to contact their child’s school directly and ask for the School Behavioral Health Coordinator to learn more about available services and to discuss their child’s needs.

Contributors:

- Charneta Scott, Ph.D. – Project Manager, Prevention and Early Intervention Division, DBH

- Erica Barnes, MSW, LICSW – Branch Chief, School-Based Behavioral Health Program, DBH

- Claudia Price, MSW, LICSW – Project AWARE State Coordinator, OSSE

- Tia Marie Brumsted, MSW, LICSW, NCSSW – Deputy Assistant Superintendent, Health and Wellness, OSSE

Kalkidan Kebede, Junior, Benjamin Banneker Academic High School

With all these resources students still feel anxious, depressed, burnout, and overwhelmed. I think Banneker has a lot of great resources for mental health, but it might not be the solution that Banneker students need.

Benjamin Banneker Academic high school has increased its mental health resources for students and staff, so that those who need help can receive it. Banneker improved and increased mental health resources as there was a rising case of suicide, depression, and anxiety amongst teens nationally.9 Banneker especially wanted its students to receive help during the pandemic.

Resources available for students at Banneker:

- Banneker provides a licensed independent clinical worker, a school psychologist, and a therapist from their partnership with Hillcrest.

- Incoming freshmen attend a summer bridge program called Banneker Summer Institute (BSI). During BSI, freshmen learn about: social-emotional learning, time management, and how to keep healthy relationships while at Banneker.

- During the pandemic, a virtual wellness series was created to teach students about important mental health skills.

- This year DCPS has partnered with Our Mind Matters, an organization dedicated to equipping teens with mental health education, resources and support. With this partnership all DCPS schools have a youth mental health ambassadors club. Mental health ambassadors created flyers and pamphlets to go around the school centered on mental health topics.

With all these resources students still feel anxious, depressed, burnout, and overwhelmed. I think Banneker has a lot of great resources for mental health, but it might not be the solution that Banneker students need. Banneker is an academically rigorous high school which is great but it’s easy for students to easily get overwhelmed. I think students can benefit from more lax policies. I hear many Banneker students share that the school is very strict. I believe adding more extracurricular activities and grade activities—senior trips, school dances, and more—along with the mental health resources that are already in place there could be an improvement in the mental wellness of Banneker students.

Chamiya Carnathan, Sophomore, School Without Walls High School

Knowing that there are plenty of resources that can help me with both my stress and mental health allows me to believe that the services meet both me and my peers’ needs.

School Without Walls provides students the ability to meet with school psychologists, counselors, social workers, and the nurse for their mental health. There is even a class called study skills which provides information on what stress is and how you can cope with it. The school also has worked with George Washington University and developed mental health groups which are designed to help students cope with stress. The groups were led by clinical psychology doctoral students at GWU and they covered topics such as coping skills, mindfulness, time management, and more.

When it comes to mental health, School Without Walls is very thorough with making sure that every student is well aware of the resources that are provided. The room numbers of every available service is posted on the newsletters, announcements, and in some teacher’s rooms. The teachers are also well aware of the stress that students go through and encourage students to use the mental health services, even if it is during class. Knowing that there are plenty of resources that can help me with both my stress and mental health allows me to believe that the services meet both me and my peers’ needs. So far, the mental health services are already the best that it can be. The school constantly talks about the importance of dealing with stress and there are already many people that we can talk to during and after school hours. Personally, getting mental health support from my school is not challenging.

Olga Price, PhD, Associate Professor – Prevention and Community Health Director, Center for Health and Health Care in Schools, Milken Institute of Public Health, The George Washington University

Despite behavioral health workforce shortages and other hurdles that have limited the city’s ability to realize the Expansion’s full potential (yet), the diverse and collective advocacy to address these challenges is strong and visible.

The investment made by city leaders, agency heads, and community advocates to improve student and family well-being has been significant and long-standing in D.C, where school mental health programs have existed for over twenty years. The more recently launched citywide Comprehensive School Behavioral Health Expansion strives to scale earlier efforts to make high-quality and responsive behavioral health interventions available across all 251 public schools in D.C.

Public schools in D.C. have also established partnerships with external organizations and providers. Schools have partnered with qualified community-based organizations (CBOs) to offer a continuum of tiered interventions in schools to minimize the impact of chronic and acute stress experienced by students across our city. Additionally over the last 3 years, the Center for Health and Health Care in Schools at GW has partnered with educators, families, and community organizations to build school and provider capacity to implement known best practices in school behavioral health through a Community of Practice (CoP) approach. This approach highlights the expertise that already exists across the community and utilizes a collaborative problem-solving approach to enhance and sustain strong implementation at the school level.

Unfortunately, barriers to developing and subsequently accessing multi-tiered supports continue due to a number of factors, including limited knowledge and awareness among students and families about the range of services offered at each school or confusion about how or from whom to initiate the referral process. Stigma related to seeking care, although not as pervasive as in years past, still inhibits some from receiving assistance even in cases where resources are evident and accessible. Furthermore, opportunities to join school behavioral health teams have exceeded the number of licensed or license-eligible child providers seeking employment in our local area.

Despite behavioral health workforce shortages and other hurdles that have limited the city’s ability to realize the Expansion’s full potential (yet), the diverse and collective advocacy to address these challenges is strong and visible. Numerous coalitions, advocacy groups, and oversight bodies, such as the Coordinating Council for School Behavioral Health, continue to push for system-wide improvements that will benefit all youth in DC. Recent reports offer some promise about the future impact of this initiative. According to the Hopeful Futures Campaign (2022), a coalition of national mental health organizations, DC has the best school social worker to student ratio in the nation and is among only two areas in the country that have met or exceeded the recommended ratio of psychologist to students.10

Furthermore the State of Mental Health in America report ranks DC as being in the top three jurisdictions with lower prevalence of mental illness and higher rates of access to mental health care for youth compared to all other states in the US besides Pennsylvania and Maine.11 Although these data represent one preliminary step it signals the city’s commitment to attending to the critical components necessary to build a comprehensive school behavioral health system for all DC students.

Endnotes

- Coffin, C. and Rubin, J. 2022. State of D.C. Schools, 2020-21. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/state-of-dc-schools-20-21/

- District of Columbia State Board of Education. 2021. Report of the Student Advisory Committee (SAC) for School Year 2020-2021. DC SBOE. Retrieved from https://sboe.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/sboe/documents/2021-07-14-SAC-Report-Final.pdf

- Coffin, C. and Rubin, J. 2022. State of D.C. Schools, 2020-21. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/state-of-dc-schools-20-21/

- Department of Behavioral Health. 2022. Updated CBO and DBH Clinicians Master List. Retrieved from https://dbh.dc.gov/node/1500291

- Coffin, C. and Rubin, J. 2022. State of D.C. Schools, 2020-21. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/state-of-dc-schools-20-21/

- PAVE. 2021. Summer 2021 PAVE End of Year Parent Survey Report. PAVE. Retrieved from: https://www.dcpave. org/school-leader-covid-19-impact-survey-april-2020/summer-2021-pave-end-of-year-parent-survey-report/

- EmpowerK12. 2022. DC must act to support our most vulnerable students. Retrieved from https://www.empowerk12.org/blog/act-for-dcs-most-vulnerable-students

- Park, Yunsoo. 2020. When students don’t feel safe in the neighborhood: How can schools help? D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/mental-healthsupports/

- According to Mental Health America, suicide is the third leading cause of death amongst adolescents. Mental Health America. 2022. Depression in Teens. Retrieved from https://www.mhanational.org/depression-teens-0

- Hopeful Futures Campaign (February 2022). “America’s School Mental Health Report Card”, Inseparables: Washington, DC.

- Reinert, M, Fritze, D. & Nguyen, T. (October 2021). “The State of Mental Health in America 2022”, Mental Health America: Alexandria, VA.