The pandemic has upended lives across the country including in the District of Columbia. D.C.’s public school students have been directly impacted by the pandemic, with all students learning from home in the spring of 2020, and most continuing at least some form of distance learning in the fall of 2020 and winter of 2021. Home and school have been integrated during a time of extreme stress and health risk, often amplifying preexisting inequities in access to resources across the city and within the household.

A companion article to State of D.C. Schools, 2019-20, which focuses on distance learning experiences, this analysis gives background on health, mental health, employment, and household resources that could influence how students have been navigating this past year.

Health

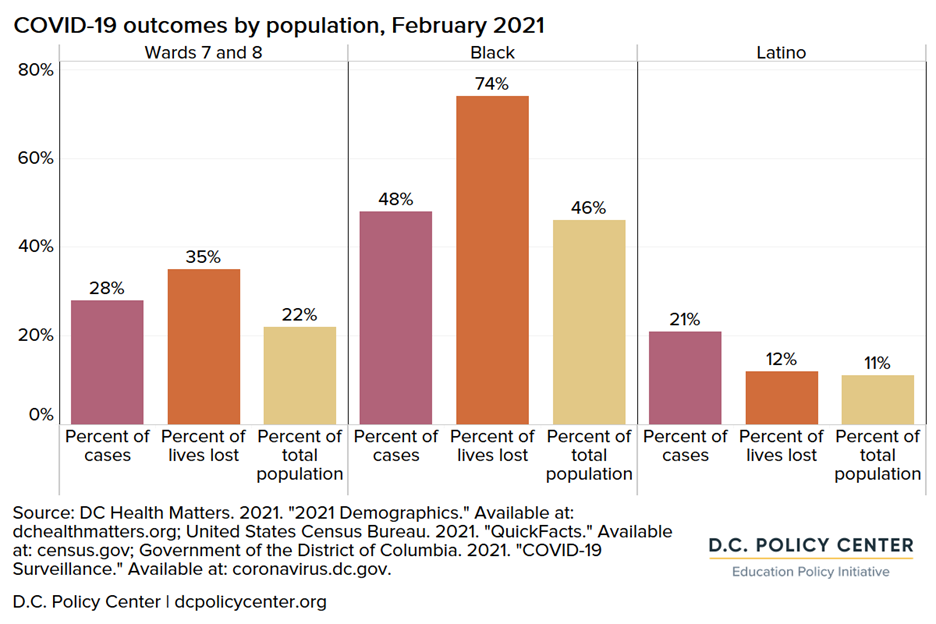

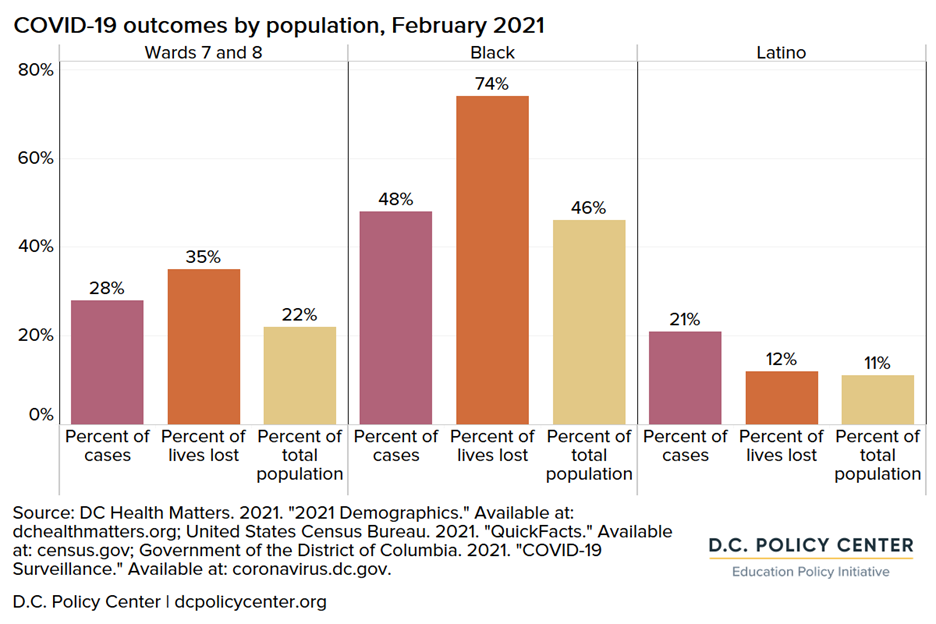

The health impacts of the pandemic have been concentrated among Black and Latino residents, likely related to unequal access to healthcare and essential work status across race and ethnicity lines, among other factors. As of February 15, 2021, residents of Wards 7 and 8 accounted for 28 percent of the District’s COVID-19 cases and 35 percent of deaths, but just 22 percent of the population. Latino residents, who make up 11 percent of the population, have also experienced a disproportionate number of cases (21 percent). The consequences of COVID-19 have been more extreme for many Black residents, who comprise 48 percent of COVID-19 cases, but a disproportionate 74 percent of lives lost as of February 2021.

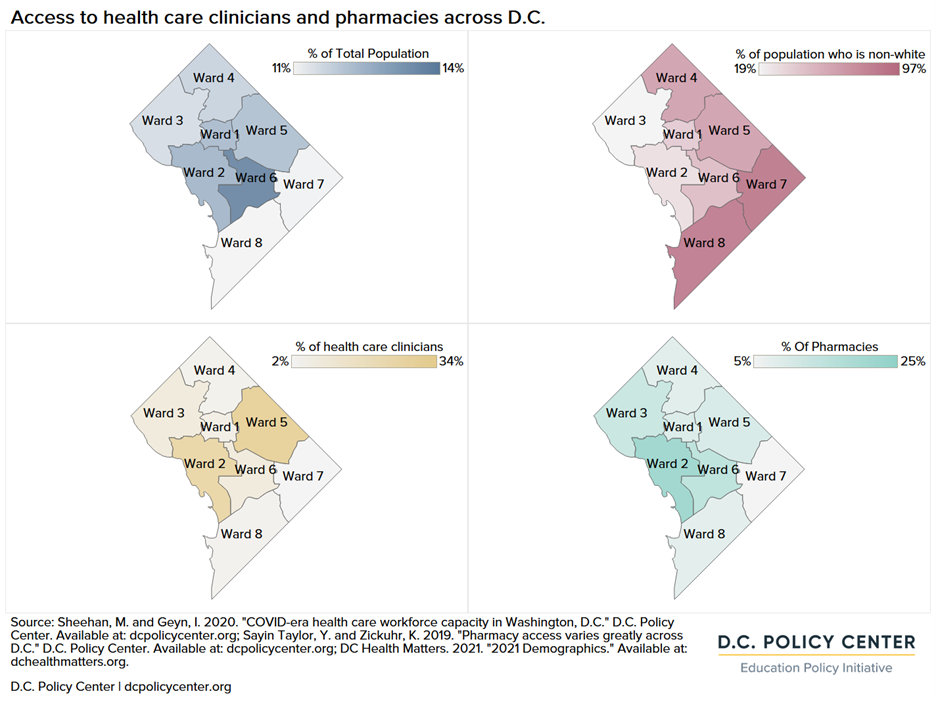

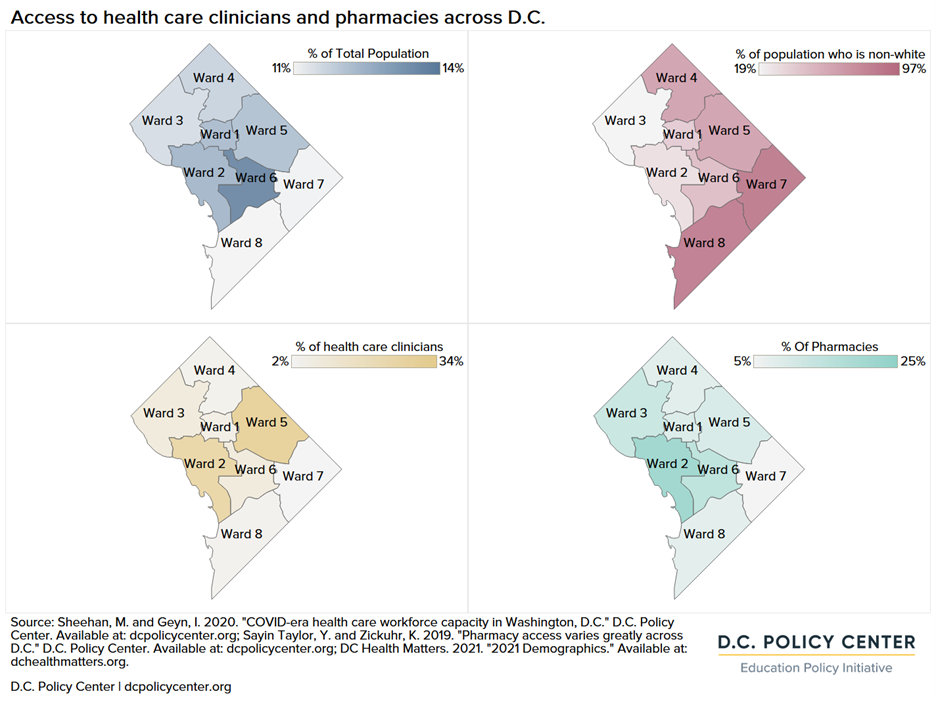

Some communities that have been disproportionately hurt by the virus also have lower access to healthcare resources. Wards 4, 7, and 8 have the highest shares of residents who identify as people of color and also lack equitable access to healthcare resources. In 2018, Wards 4, 7, and 8 had less than half the provider capacity necessary to serve their residents for primary care visits: 5 percent of D.C.’s health care clinicians are in Ward 4, compared to 12 percent of the city’s population; 2 percent are in Ward 7 compared to 11 percent of the population; and 4 percent are in Ward 8 compared to 11 percent of the population.[i] Ward 5, on the other hand, has 34 percent of D.C.’s health care clinicians and 13 percent of the population.

These same wards that have low access to primary care physicians often also lack options for pharmacy services. Out of 145 licensed pharmacies in the District of Columbia, 36 were located in Ward 2 and 25 were in Ward 6, while Ward 7 only had seven and Ward 8 had 12 in 2016.[ii]

Insurance status can also act as a barrier to accessing health care. The District has had one the country’s lowest uninsured rate for children — at two percent (a percentage shared with four other states), but the uninsured rate for children living in Wards 7 and 8 in recent years has been higher, at three percent.[iii]

Mental health

Even before the pandemic, a large share of the District’s children and youth up to age 17 had been exposed to traumatic events with the potential to impact their mental health: 23 percent had been exposed to one adverse childhood experience (ACE) [iv] and 21 percent had been exposed to two or more.[v] Exposure to these incidents is much higher among D.C’s Black and Latino children and youth: 17 percent of white students have been exposed to an ACE, compared to 59 percent of Black students and 39 percent of Latino students.[vi]

| Adverse Childhood Experiences |

| ACEs undermine a child’s sense of safety and stability. They include abuse, neglect, exposure to violence at home or in the community, substance misuse, and instability due to parental separation, to name a few.[vii] They also include social factors such as economic hardship, homelessness, and discrimination. Decades of research link ACEs to lifelong negative health and social outcomes.[viii] One such study found that people with four or more ACEs – one in six adults – are at increased risk for alcoholism, depression, suicide attempt, severe obesity, and other health hazards.[ix] Another study linked ACEs to five of the top 10 leading causes of death.[x] Exposure to ACEs also leads to reduced educational and occupational achievement.[xi] |

Living through the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic experience in and of itself, but it also puts children at risk of encountering ACEs. Social isolation in response to the pandemic likely increases the chances of anxiety and depression among D.C.’s children and youth.[xii] Some children are also experiencing increased economic hardship, one of the most common ACEs.

Other children are suffering from the effects of compromised parenting caused by the pandemic. According to the Household Pulse Survey[xiii], 31.4 percent of adults in D.C. reported symptoms of anxiety or depression in April compared to 45.6 percent in early November.[xiv] High anxiety and depressive symptoms among parents are positively correlated with child abuse potential.[xv] However, many fear that due to stay at home orders, much of the abuse is going undetected. In D.C. alone, reports of child abuse between mid-March and mid-April were 62 percent lower than in the same period last year.[xvi] School closures also contribute to the underreporting of child abuse, as educators typically report more instances of child abuse than any other group. In 2018, educators were responsible for 21 percent of 4.3 million reports.[xvii]

Employment and labor force participation

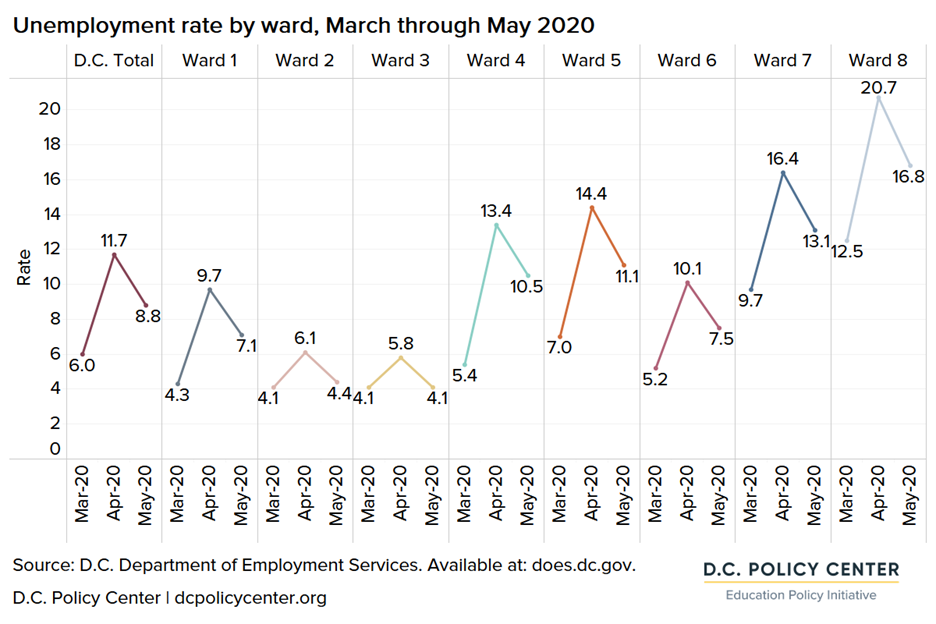

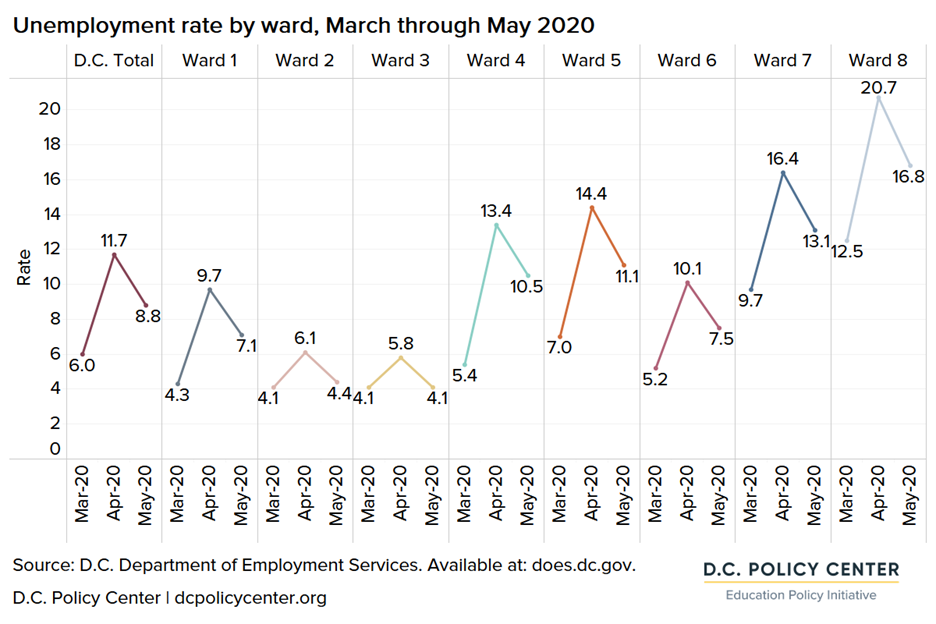

Immediately following the declaration of a public health emergency in mid-March 2020, the unemployment rate[xviii] in D.C. increased by 5.7 percentage points, to 11.7 percent by mid-April – the highest rate in recent history. All wards experienced job losses, but the unemployment rate was highest in Ward 8, at 20.7 percent. Over the same period, 39,619 residents lost their jobs, and 18,052 residents exited the labor force.[xix] This exit explains some of the declines in the unemployment rate as of May, a metric that only incorporates those residents who are either employed or actively looking for work. For example, in Ward 2 and 3, the unemployment rate returned to pre-pandemic levels in a matter of weeks, not because employment opportunities returned, but because a larger share of workers dropped out of the labor force, citing the need to take care of a child or an elderly parent.[xx]

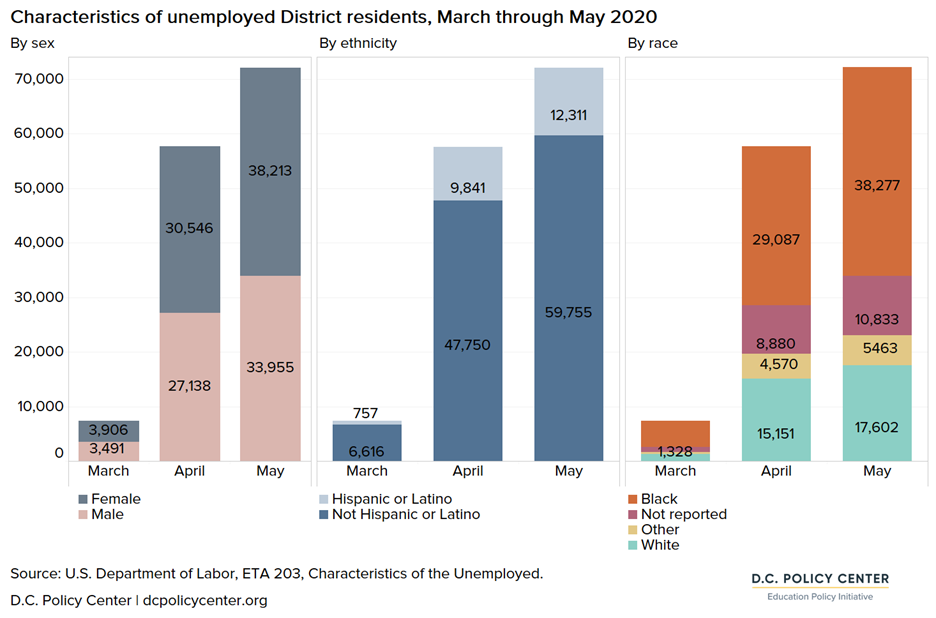

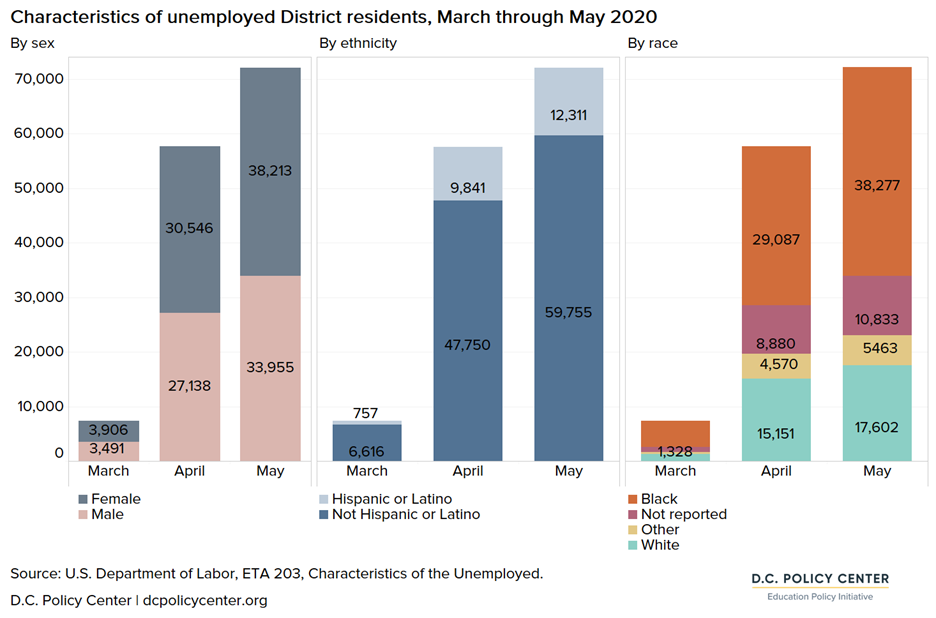

Throughout the pandemic, women and Black and Latino residents experienced the worst economic losses. According to Department of Labor data on individuals receiving unemployment insurance benefits, women in the District experienced greater job losses than men. In March 2020, women and men were unemployed in roughly equal numbers, but by April, unemployed women outnumbered men by 3,408. The number of Hispanic or Latino unemployment claimants was 13 times higher in April than in March, increasing from 757 to 9,841. Black workers receiving unemployment benefits saw a five-fold increase, compared to a ten-fold increase among white workers, but Black workers had made up the largest share of recipients in April 2020.

Household resources

In the spring of 2020, distance learning meant students were in their homes most of the time, making them more dependent on their households than they had been before–and some household factors presented challenges in weathering the pandemic to continue learning.

First, lack of access to devices and high-speed internet prevented many students from fully participating in distance learning, especially in households with multiple students or parents working remotely. Approximately one in every eight District residents did not have access to a computer or tablet in their household before the pandemic.[xxi] 24 percent of children in D.C. lacked access to broadband internet–and this share was higher in Wards 7 and 8, where 37 percent of children lacked access.[xxii]

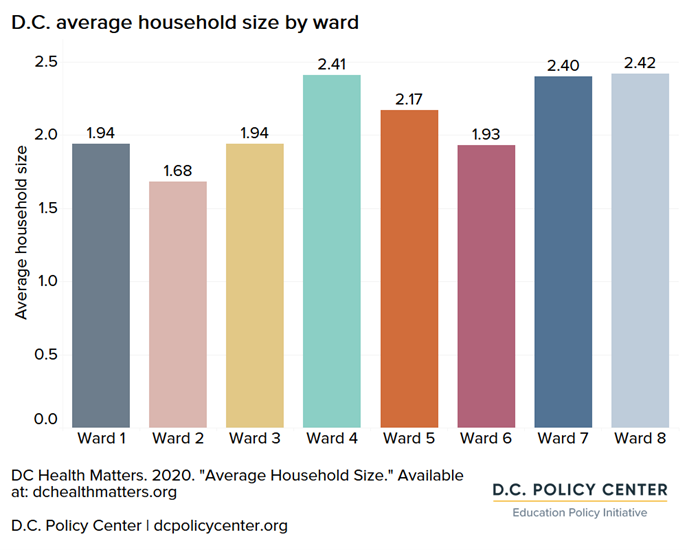

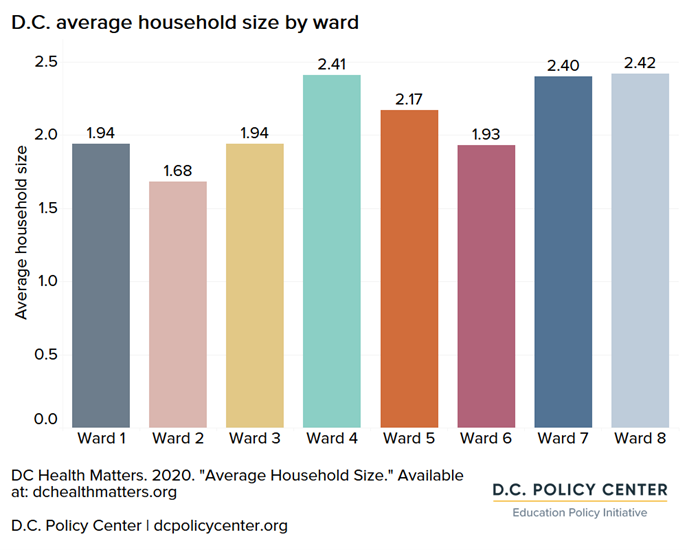

In addition, large households made some students and families more susceptible to contracting COVID-19: one of the strongest causes of COVID-19 transmission has been exposure between members of the same household. Wards 4, 7, and 8 had the highest average household sizes at 2.4 people, compared to 1.6 people in Ward 2, and 1.9 in Wards 1, 3, and 6.[xxiii]

Transportation also became more challenging for many households, making it difficult to commute to work, go to the grocery store, or seek services such as healthcare. An estimated 46 percent of D.C. households do not have a vehicle available, and access to a vehicle is generally lower in many Ward 7 and 8 neighborhoods.[xxiv] Reliance on public transit likely became more complicated during this time, with many Metrobus routes eliminated or scaled back and less frequent Metrorail service. Using public transit became undesirable for many, due to the risk of increased exposure to COVID-19.

Implications for students

The pandemic and distance learning have exacerbated barriers to learning that some students were already experiencing before March of 2020. During the pandemic, students became more isolated and dependent on their households than before, with less access to resources from schools and others. Many households experienced a loss of earnings, more complicated work arrangements, increased levels of stress, COVID-19 infections, or other serious challenges that made learning at home more difficult. Given pre-existing disparities in the District, the pandemic’s impact has likely been even greater for students of color and students from low-income families compared to their peers–and these effects will likely reverberate in the years to come.