Most students in the District of Columbia have been learning from home since the COVID-19 pandemic began in March of 2020. School closures have likely been more challenging for students living in low-income households than for those in higher income households – households in Wards 7 and 8 are less likely than households in other wards to have access to a device for distance learning and less likely to have broadband internet access.[1] Additionally, early data show that at-risk students (most of whom are eligible for TANF or SNAP) were likely to experience more learning loss by the fall of 2020 than not at-risk students.[2]

These disparate learning experiences for students living in low-income households usually coincides with disproportionate economic effects of the pandemic.[3] Economic disruption, like stay-at-home orders, affects job security, especially for lower-income jobs.[4] In the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic as many cities and states closed restaurants, bars, and public spaces, many residents scrambled for extra supplies and food – and this was more challenging for households with less money available to do so.[5] As the pandemic continues, job losses are expected to push many families into extreme poverty. In April 2020, Pew Research reported that over 43 percent of families in the U.S. experienced income loss by a member of the household.[6] In D.C., in November 2020, the unemployment rate was 2.2 percentage points higher than the previous year around the same time.[7]

Furthermore, experiencing poverty prior to the pandemic puts families at a disadvantage to fulfil their needs. Low- and middle-income families are least likely to have funds set aside to cover expenses in case of an emergency like loss income or unemployment.[8] Further, from July 9 through July 21, 2020, about 63,000 (or 12 percent) of adults in the District reported living in a household where there was not enough food to eat in the last seven days. The rate more than doubled to 25 percent for adults in D.C. households with children over the same period.[9]

COVID-19 has been widespread in the District of Columbia. As of November 30, 2020, at least 21,685 residents have tested positive for COVID-19, an estimated three percent of the population.[10][11] Nine percent of the District’s positive cases are young people under the age of 18.[12] Given the reach of COVID-19, students are likely to have personally or had a family member contract and transmit COVID-19, develop other illnesses and diseases after contraction, or have had a family or friend die because of COVID-19 related complications.[13]

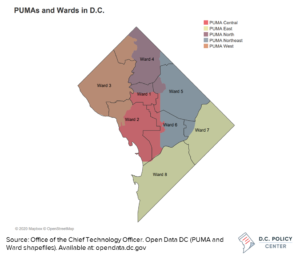

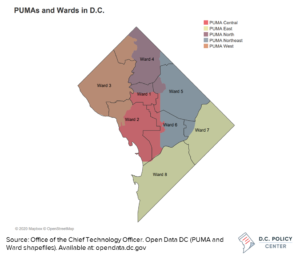

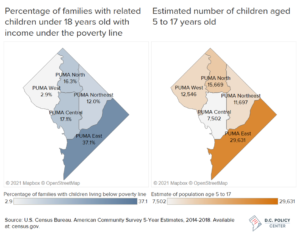

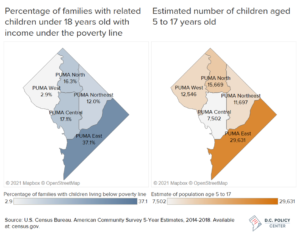

There are also several factors that could make some children in D.C. more vulnerable to COVID-19’s economic impacts. This analysis uses 2014-2018 data from the American Community Survey at the PUMA (Public Use Microdata Area) level to reveal where in the city students might be most affected by the pandemic. Census data divides D.C. into five PUMAs, the unit of interest for this analysis, but D.C. is divided into eight wards for municipal purposes. The map below shows the overlap between wards and PUMAs in D.C.

Children in the District are more likely to live in lower income neighborhoods

In D.C., PUMA East, the area corresponding to Wards 7 and 8, is home to the highest number of families with school-aged children as well as the highest number of families living below the poverty level.[14] In PUMA East, 37.1 percent of families with children had incomes below the poverty level, while the city average is 20.1 percent. On the other side of the city in PUMA West, only 2.9 percent of families with children have incomes below poverty level.[15] Of families living below the poverty level, 43 percent of families in PUMA East, 30.3 percent of families in PUMA Central and 19.2 percent of families in PUMA Northeast had school-aged children. Living below the poverty line during a pandemic can mean not being able to pay for unexpected financial costs, not being able to purchase enough food, and puts families at higher risk for not being able to pay rent.

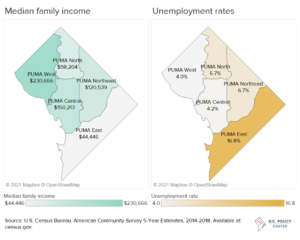

In addition, PUMA East has the highest unemployment rate of 16.8 percent, compared to D.C.’s overall unemployment rate of 7.4 percent. PUMA East also has the lowest median income of D.C.’s PUMAs at only $44,446 compared to D.C.’s median income of $106,528. For students, higher unemployment and lower income could mean not having access to stable home conditions or the resources, like internet, needed to be successful in a virtual learning environment.

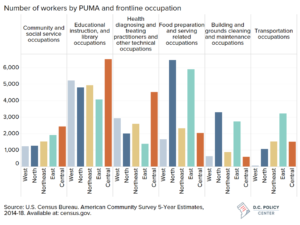

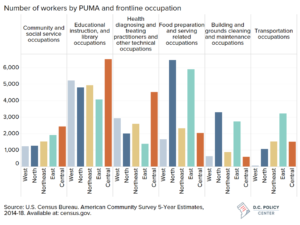

In D.C., PUMA East has disproportionately more workers working in-person in frontline occupations than other PUMAs in D.C.[16] For example, PUMA East has the highest number of workers working in transportation and the second highest number of workers in the food service industry.[17] Frontline occupations do not necessarily translate into higher wages: PUMA East has the largest number of transportation workers but the lowest median income of all transportation workers.[18] These positions also require frequent human interaction that constrains social distancing. As the PUMA with the most school-aged children, this means more students are at risk of contracting COVID-19 as they are more likely to live in houses with frontline workers, or youth could be frontline workers themselves.[19]

As COVID-19 cases continue to rise across the country, it is important that we consider the adverse impacts of COVID-19 and the ways it impacts students, especially as more schools continue to reopen for in-person learning. There are numerous factors that put students at a greater risk of facing economic hardships or being disproportionally impacted economically due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on where a student lives in the District, they may be more likely to live in a household where lost wages and unemployment have impacted income or families may not have the resources to support the entire family during the pandemic.[20] It is important that we consider students in our analysis and policy decisions. Schools that have reopened have already faced challenges with COVID-19 transmissions.[21] However, challenges with learning loss, technology, and family ability to support virtual learning, especially for students that receive additional services (including special education or English learner supports), may require many students to deal with the risk of entering school buildings.[22] The challenges students face are exacerbated by the disproportionate economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, putting low-income students and students of color at a learning disadvantage.