D.C.’s Capital Bikeshare was one of the first big bike share systems in the United States, on the heels of similar systems installed in Paris and Montreal.[1] Offering docks full of bikes all over the central part of the District, with some additional service in outlying neighborhoods and in the suburbs, it allows people to bike without owning their own bicycle, for a small subscription fee.

Since its opening in 2010, other American cities have opened their own systems. The biggest is by far New York’s Citi Bike, and today Capital Bikeshare and Chicago’s Divvy are in a near-tie for second place.

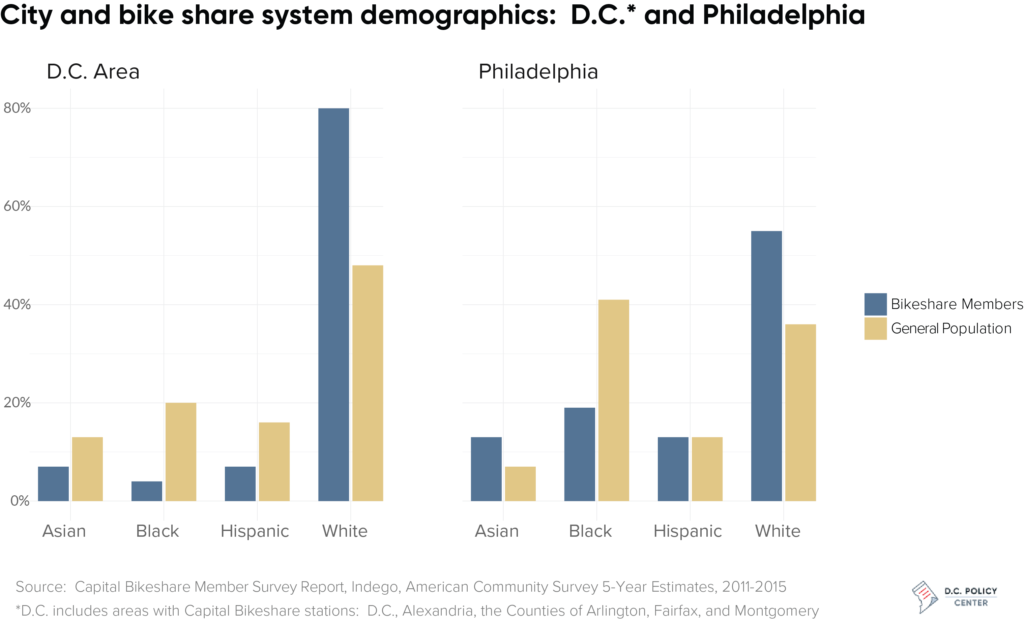

Yet despite its general success, looking at Capital Bikeshare’s users reveals stark disparities by race and ethnicity. The District is 36 percent white and 48 percent black; counting Arlington and Alexandria, which have extensive Capital Bikeshare service as well, the core is 35 percent black.[2] But a survey from 2016 reveals that 80 percent of subscribers are white (and just 4 percent are black), and 52 percent of subscribers are in households earning more than $100,000 a year.

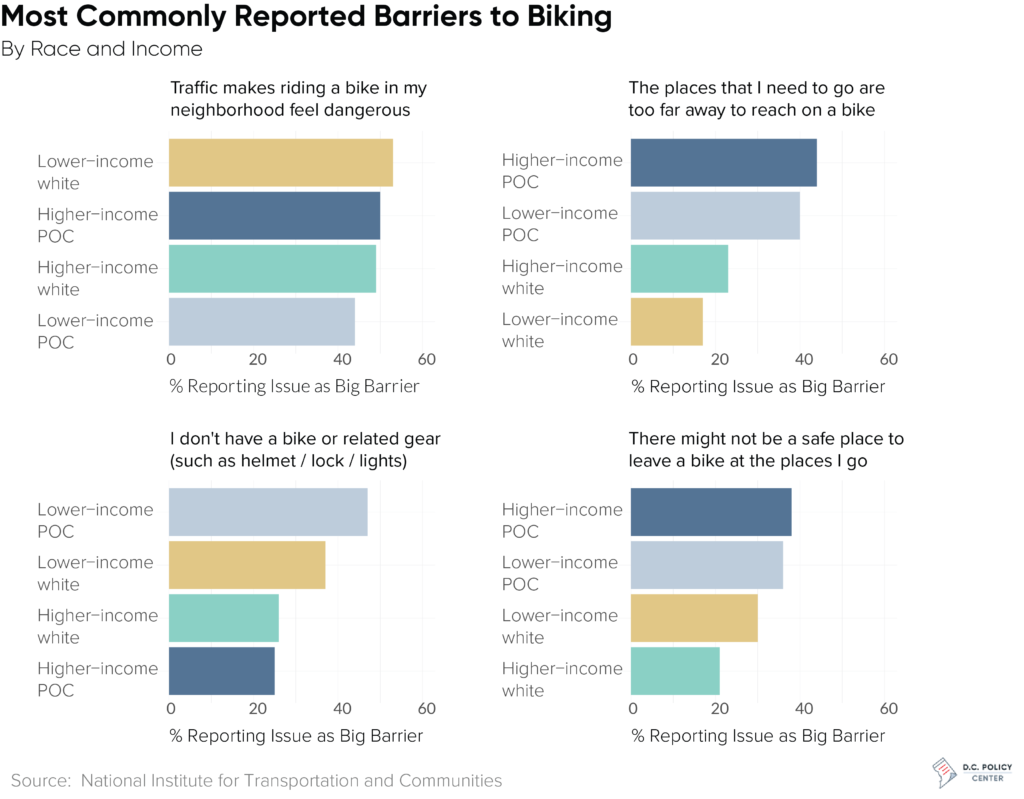

A recent study of residents living in predominantly low income and/or nonwhite neighborhoods in Philadelphia, Chicago, and Brooklyn found that “the biggest barrier to bicycling generally is concern about traffic safety, regardless of race or income.” This is a major underlying issue that extends beyond bike share system design, and one that cities should address directly so that all residents can safely navigate the city without a car. However, other frequently-cited barriers involved issues that an affordable, well-designed bike share system would be able to address: more than a third of lower-income respondents of color said that a barrier was lack of equipment (such as a helmet), destinations being too far away, the expense of owning a bike, and the lack of a safe place to park or store a bike at home or at their destination.[3] (It’s also worth noting that for the whole sample, women were significantly more likely to voice all of these concerns than men.)

Disparities in bikeshare usage aren’t unique to D.C., and there are lessons to be learned from other cities that have sought to improve access and usage of their local bike shares. Among the better practices that Capital Bikeshare should adopt, many have been implemented in Philadelphia, whose Indego system has had more success in reaching out to nonwhite city residents.

Coverage: How widely should Capital Bikeshare spread its docks?

Bikeshare systems face a tradeoff between bike density and coverage. Cities can choose to blanket one central area with docks with many bikes each, or they can spread bikes around many neighborhoods, with a few docks in each community center. Citi Bike is an extreme example of prioritizing density: despite being the largest bike share system in the United States, it is only now beginning to serve Harlem, just three miles north of Midtown Manhattan. Other American systems, including D.C.’s, aim to provide a compromise between density and coverage.

In Capital Bikeshare’s case, this means a very high density in a central zone roughly from the Capitol to Rock Creek, and lower density elsewhere. There are approximately 30 docks east of the Anacostia River, particularly along major streets, but they are relatively sparse. There are also relatively few docks in D.C.’s farther northeastern reaches, such as Langdon, Woodridge, and Michigan Park, in the northernmost neighborhoods around Rock Creek Park, and in the Palisades and other neighborhoods along the Potomac.

The D.C. area’s pattern of high bike density in the core and low density outside is also common in Chicago. However, there are two crucial differences. First, Divvy’s high-density zone in Chicago is larger, at the cost of slightly less density there than in Washington near Metro Center and Farragut. And second, Divvy’s lower-density areas, mainly on the South Side, still offer docks roughly on a half-mile grid; Capital Bikeshare has about the same density east of the river, but the docks there are haphazard, with long gaps in coverage.

Capital Bikeshare could aim to provide a regular grid east of the Anacostia River, but this would run into a complication that does not exist in Chicago—hills. Chicago is flat, but D.C. neighborhoods east of Anacostia are hilly, and do not have an easy street grid. One possible way around this would be to place docks along the busiest roads at regular intervals, offering an alternative to bus service. Docks on major streets are highly visible to people who now walk or ride public transit, and the system already uses this approach in Northern Virginia, in Georgetown, and along 14th Street Northwest.

I also spoke to two outreach coordinators at Philadelphia’s Indego system, Aaron Ritz and Waffiyyah Murray. They said that one key part of Indego’s strategy is to provide docks for recreational ridership rather than work trips. Ritz said that national surveys show that people of color who ride bikes are more likely to do so for non-work trips, including leisure trips through parks, and also visits to family members outside walking distance. Based on this information, as well as community preferences, Indego installed some of its docks near parks and trails; its aim is to instill habits of regular bike ridership in people, who would later begin to use the bikes to travel to work. While Capital Bikeshare appears to have sufficient coverage of parks, it could add docks at other recreational spaces in low-coverage areas, and increase coverage in residential areas to help people use bikes to visit family and friends.

The challenge of outreach

Research suggests that some of the most common ways people hear about bike share systems are through seeing the kiosk (51 percent) and by word of mouth (40 percent), online (29 percent), from ads on buses or bus shelters (25 percent), and on television (20 percent).[4] However, higher-income white respondents were not only far more likely have heard about these services through all of these channels (except television) than lower-income respondents of color, they were also much more likely to have heard about bike share from more than one source. Systems therefore must make a more concerted effort to reach all communities.

Within the United States, Philadelphia has worked especially hard in community outreach to lower-income and nonwhite city residents. From the start, it aimed at providing at least 30 percent of its stations in low-income neighborhoods. Waffiyyah Murray, one of the outreach coordinators for Philadelphia’s Indego system, said that outreach is critical: “You can develop as many programs as you’d like, but if people don’t know them, it’s pointless.”

Philadelphia’s Indego bike share system is still disproportionately white compared with the city as a whole, but its disparities are not nearly as stark as in D.C. In 2016, Indego’s user base was 55 percent white (compared with 36 percent of Philadelphia residents), 19 percent black (compared with 42 percent of residents), 13 percent Asian (7 percent of residents), and 7 percent Hispanic (13 percent of residents). Meanwhile, as noted earlier, Capital Bikeshare’s users are 80 percent white and just 4 percent black.

Ritz and Murray said that Indego connected with community leaders in each neighborhood it was about to enter, beginning a dialog about how to serve the community. In these conversations, Indego would explain the system, partnering with local organizations to teach bike safety; in the other direction, it would solicit ideas about where to place docks to best serve the community. Ritz explained it as “people who’ve lived in the neighborhoods are experts on their own areas.”

Additional outreach in targeted communities is clearly a first step for any equitable expansion, but it’s also clear that this outreach must be a two-way street. Instead of simply educating or informing residents of the system and how it works, successful outreach must involve listening to residents’ needs and concerns to address them. For some neighborhoods, this may also involve additional marketing and community discussions in Spanish and other languages other than English.

Fare payment and other financial concerns

But outreach cannot by itself convince low-income users to ride the system. There is a real problem with fare payment. Capital Bikeshare, like the other major American systems, offers heavily discounted memberships to qualifying low-income people. However, three major problems remain.

First, applying for reduced-price memberships involves red tape. Whereas other American cities such as Philadelphia, Chicago, and San Francisco offer special programs targeted at low-income users, Capital Bikeshare has an inscrutable mix of financial assistance programs, which require people to go through a community partner organization rather than letting them sign up directly. By contrast, Chicago’s “Divvy for Everyone” has simple eligibility rules (300 percent of the federal poverty line), and Indego and San Francisco’s GoBike offer steep discounts to people eligible for means-tested welfare programs such as food stamps. In contrast, Capital Bikeshare has three distinct systems, with unclear eligibility rules.

Second, the system is intimidating. As the survey of riders in Philadelphia, Chicago, and Brooklyn reveals, one of the concerns low-income residents have is the possibility of excessive fees for not returning a bike; the license agreement deters some users, even if very few users ever actually incur the fines. CityLab reports that Chicago is setting up a fund to cover liability for unbanked members, and outreach can also help ensure potential members understand their options.

And third, there is no easy way to pay for Capital Bikeshare without a bank account and a credit card. While almost everyone in the middle class has access to banking, not every poor city resident does; according to FDIC data from 201, 10.8 percent of households in the District are unbanked. In D.C., 35.3% of households earning less than $15,000 annually are unbanked. There is a cash option at five locations in Arlington, but not in the District, where lower-income households in the system’s current coverage area are concentrated; but the only option Capital Bikeshare offers for unbanked people in D.C. works through opening an account with a credit union. Meanwhile, Divvy for Everyone and Indego and GoBike’s systems all allow qualifying low-income users to pay with cash.

The lack of access for unbanked users is a national problem; despite the attempts made in Chicago, Philadelphia, and San Francisco, there is no working model of a city that has been successful in fully serving its low-income residents, and the private companies that provide the infrastructure have not prioritized equitable access for low-income people. But some within the industry have tried, so far unsuccessfully, to provide other options. One possibility is electronic benefit transfer (EBT) cards, which many low-income residents receive for food stamps and other cash benefits. Food stamp benefits can only be used for food purchases, but it is possible to load money into EBT cards independently of the program. Another possibility is library cards; bike share users could load bike share funds on to the cards, provided the public library system agrees to let cardholders spend money on bike share.

Dockless bikeshares systems have many of the same barriers as traditional systems

Dockless companies got their start in China, and are now entering the United States—including D.C. Dockless bikes do not have fixed stations; users unlock bikes with smartphone apps, and can leave bikes at their destination (instead of at a designated station) when they are finished with their trip. With less fixed infrastructure than traditional bike share systems, dockless systems can provide far more bikes for the same budget.

Unlike Capital Bikeshare, which is a public-private partnership, D.C’s dockless services (Mobike, LimeBike, Spin, and JumpDC) are fully private enterprises. Their pricing also differs from that of Capital Bikeshare and other conventional systems: most let users make short trips for $1 per 30-minute ride without any additional commitment, but their unlimited monthly subscription rates are much higher than Capital Bikeshare.[5]

Based on the services’ initial rollout, it appears that two of the three main problems of bike share equity—outreach and fare payment—are even worse for dockless bike share. There does not appear to be much community outreach, and the fare payment options (which require a bank account and credit card) lock out many low-income residents. In addition, dockless systems also require a smartphone for activation. Smartphone ownership is universal among middle-class Americans, but not among poor Americans: according to Pew Research, only 64 percent of American households making less than $30,000 a year have a smartphone.

While dockless systems offer some promise in expanding bike share access through increasing the overall number of bikes available, they are unlikely to solve traditional systems’ problems with economic and racial disparities. It is likely that once enough time has passed for the dockless companies to publish statistics about user demographics, they will turn out to be as white, wealthy, and educated as those of Capital Bikeshare.

Conclusion

The United States adopted the bike share concept from France and French Canada, and imported many technical concepts successfully—such as importing dockless bike share systems from China. But the specific American context around racial segregation and lack of access to banking requires new methods to ensure that bike share can serve the entire city, and not just the white middle and upper class. Fortunately, there are already some good American models for what Capital Bikeshare should do, including some practices that have already been adopted and others that are under discussion.

To improve coverage, Capital Bikeshare needs to expand its coverage in underserved neighborhoods within the District, in line with community needs. This means more stations and more bikes east of the Anacostia River and north and east of Columbia Heights. The precise choice of where the docks should do should involve dialogue with these respective communities, with bikeshare providers actively listening to concerns and trying to make the system more accessible to low-income or unbanked users.

It is not inevitable for bike share to appeal just to the educated urban middle class; in the bikeshare equity study, 74 percent of low-income respondents of color said that their city’s bike share system “is useful for people like me.”[6] There are specific targeted programs concerning pricing, accessibility, and outreach that could appeal to the urban working class. Capital Bikeshare can adopt practices started by Philadelphia and Chicago, and equitably expand the program’s access and use to all D.C. area communities. Just as D.C. pioneered bike share in the United States, it can also pioneer accessibility for everyone, regardless of race, ethnicity, or income.

Footnotes

[1]Capital Bikeshare launched in September 2010, and by the end of the year had over 1,100 bikes in D.C. and Arlington. Elsewhere in the U.S., bikeshares had also already launched in Minneapolis and Denver.

[2]Capital Bikeshare coverage extends further into Virginia and into Maryland, but this piece focuses on areas with extensive coverage.

[3]McNeil et al., “Breaking Barriers to Bike Share: Insights from Residents.” p 100. Responses were among able respondents under age 65.

[4] McNeil et al.

[5] For instance, Spin offers monthly subscriptions for $29, while Capital Bikeshare costs $8 per month with an annual commitment, or $85 per year.

[6] McNeil et al., p 129. Responses were among able respondents under age 65.

Feature photo by Ted Eytan (Source).

Alon grew up in Tel Aviv and Singapore. He has blogged at Pedestrian Observations since 2011, covering public transit, urbanism, and development. Now based in Paris, he writes for a variety of publications, including New York YIMBY, Streetsblog, Voice of San Diego, Railway Gazette, and the the Bay City Beacon. You can find him on Twitter @alon_levy.