The D.C. Council is considering six separate bills that would amend the District’s rent control laws. Among these six, B23-873, the Rent Stabilization Program Reform and Expansion Amendment Act of 2020, which reflects the policy proposals of the “Reclaim Rent Control” platform, offers the most comprehensive and sweeping changes, affecting every aspect of the law including the number of eligible units, the calculation and timing of rent increases (including increases on vacant units,) and the petition processes housing providers use to raise rents in order to make improvements to their buildings. If enacted, the bill would impact a wide array of housing providers in the city, including the rents they could charge, the returns they could realize, and the future valuations of their buildings. These changes—particularly the impacts on building valuations–would affect the tax revenue the city collects.

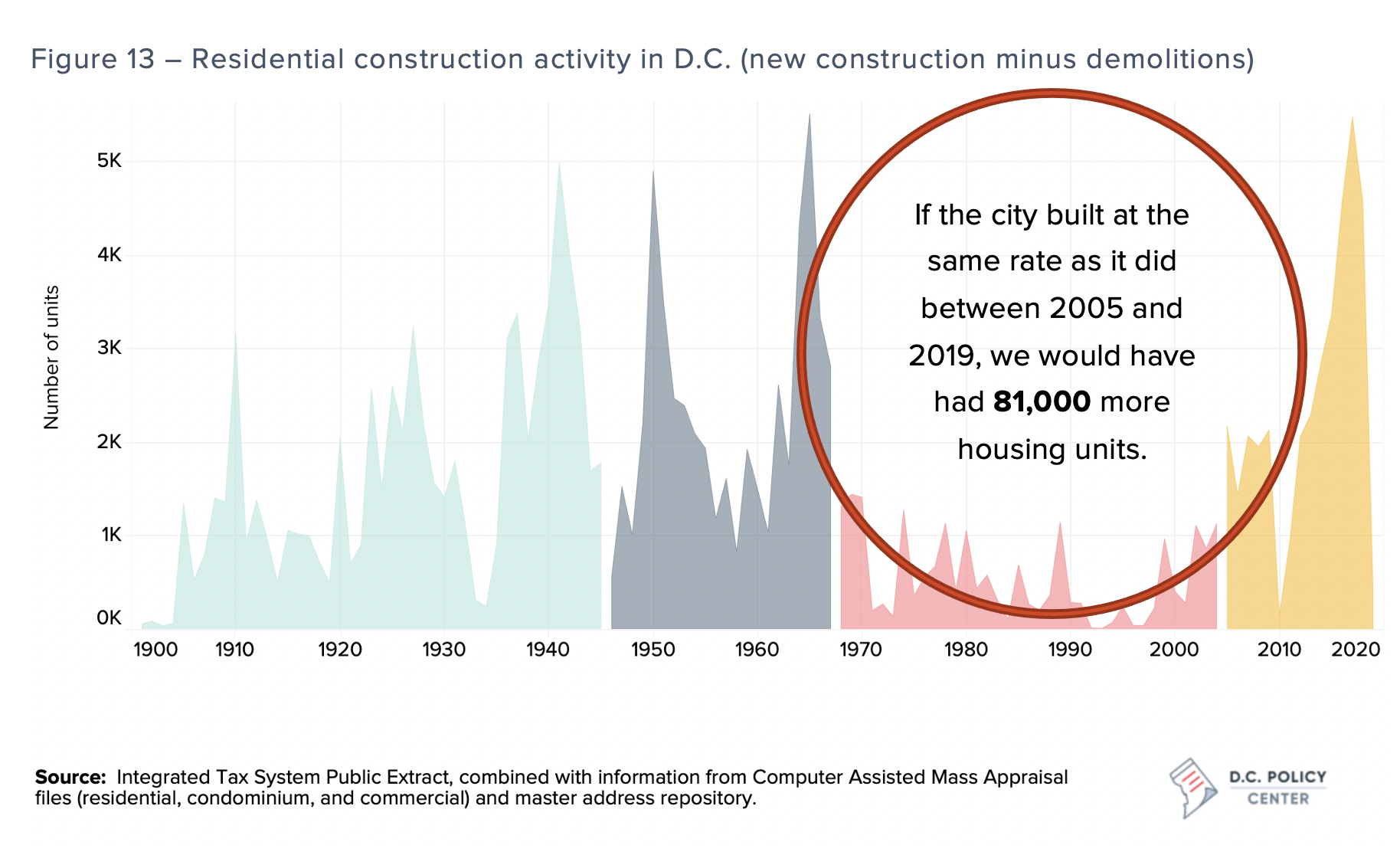

By the end of 2019, the District had an estimated 113,281 taxable rental apartment units. These units were collectively valued at $22.5 billion and generated annual tax revenue of $192 million for the city. Since 2006, the city has been adding a net average of 2,000 rental units per year, increasing yearly assessed values by $615 million. Rents for these buildings have grown at an average rate of 3 percent between 2006 and 2020.

Using the rental housing database compiled by the D.C. Policy Center for its comprehensive review of rental housing in the District, this policy brief examines the bill’s potential impacts on the District’s rent-controlled stock, rents, property valuations, tax revenue, and the future of the city’s rental housing.

The main findings of this report are the following:

Limiting exemptions from rent control will likely expand the stock and shift it toward Wards 5 and 6.

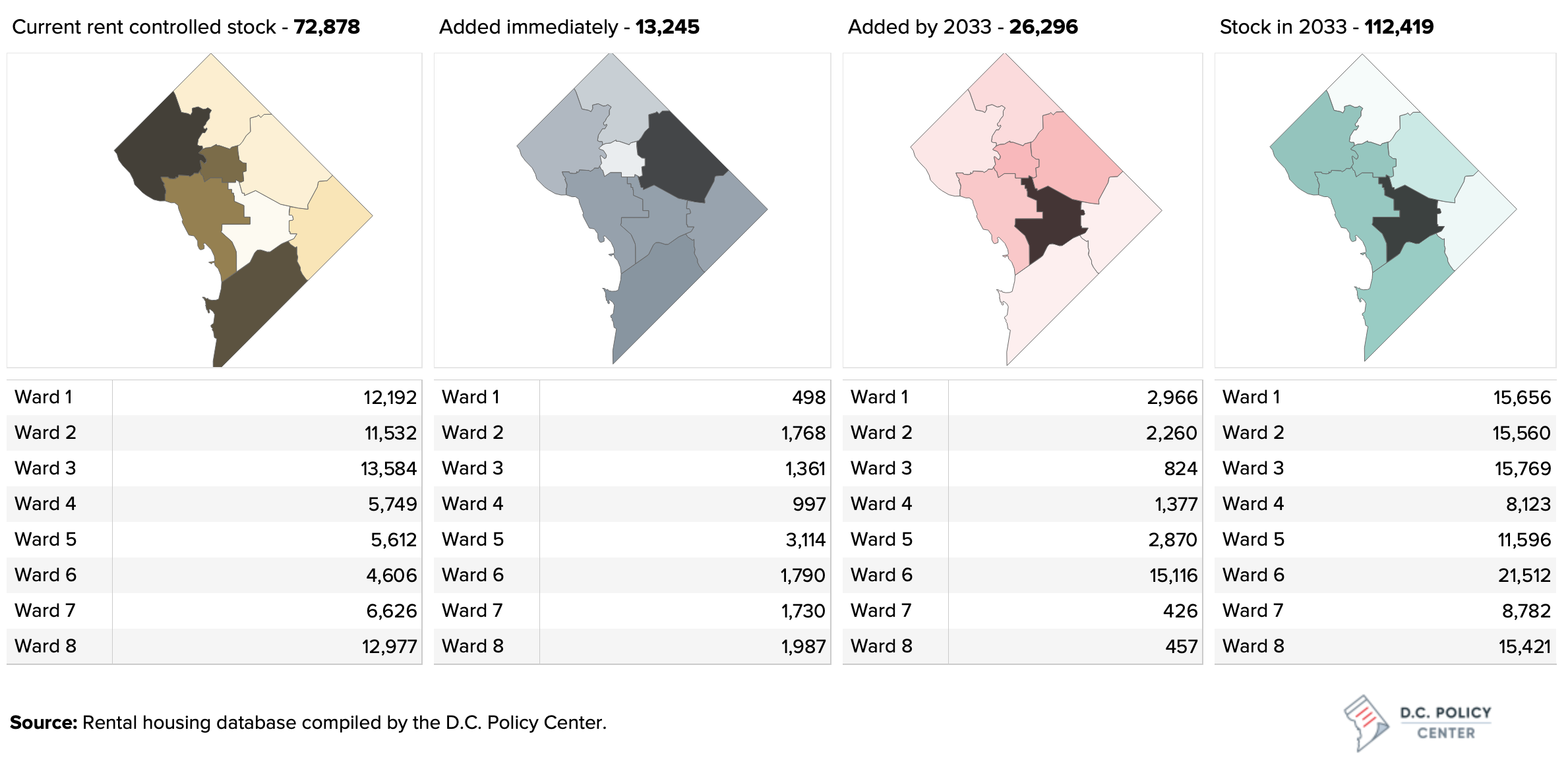

Current law exempts from rent control buildings that acquired their construction permits after 1975, and housing providers who own fewer than five units. With these exemptions, the city has an estimated 72,878 rent-controlled units in 2,157 rental apartment buildings. B23-873 would limit the exemptions to buildings built in the last 15 years and to housing providers who own fewer than four units.

Limiting exemptions to large multifamily buildings built in the last 15 years would immediately expand the rent-controlled stock by 4,705 units (a 6 percent increase). Each year following the possible adoption of B23-873, additional buildings and units would be subject to rent control. For example, 14 years following the adoption of B23-873, an additional 25,006 units in 157 buildings would become subject to rent control, potentially increasing the rent-controlled stock by 42 percent from its current (2020) level.Ward 6 could see the largest increase in rent-controlled stock from the proposed 15-year rolling exemption. 58 percent of the units in large multifamily buildings built since 2005 are in Ward 6

Limiting the exemptions to providers with fewer than four units (compared to fewer than five units under current law) could add 2,164 buildings with 8,656 units to the rent-controlled stock (an 11 percent increase over the current base). As the majority of these buildings were built before 1977, this impact would be immediate. Wards 5, 7, and 8 would see the largest impacts from expanding rent control to providers with four units. Three quarters of such small buildings are in these three wards.

The “CPI-only” rule will lower future rent trajectories.

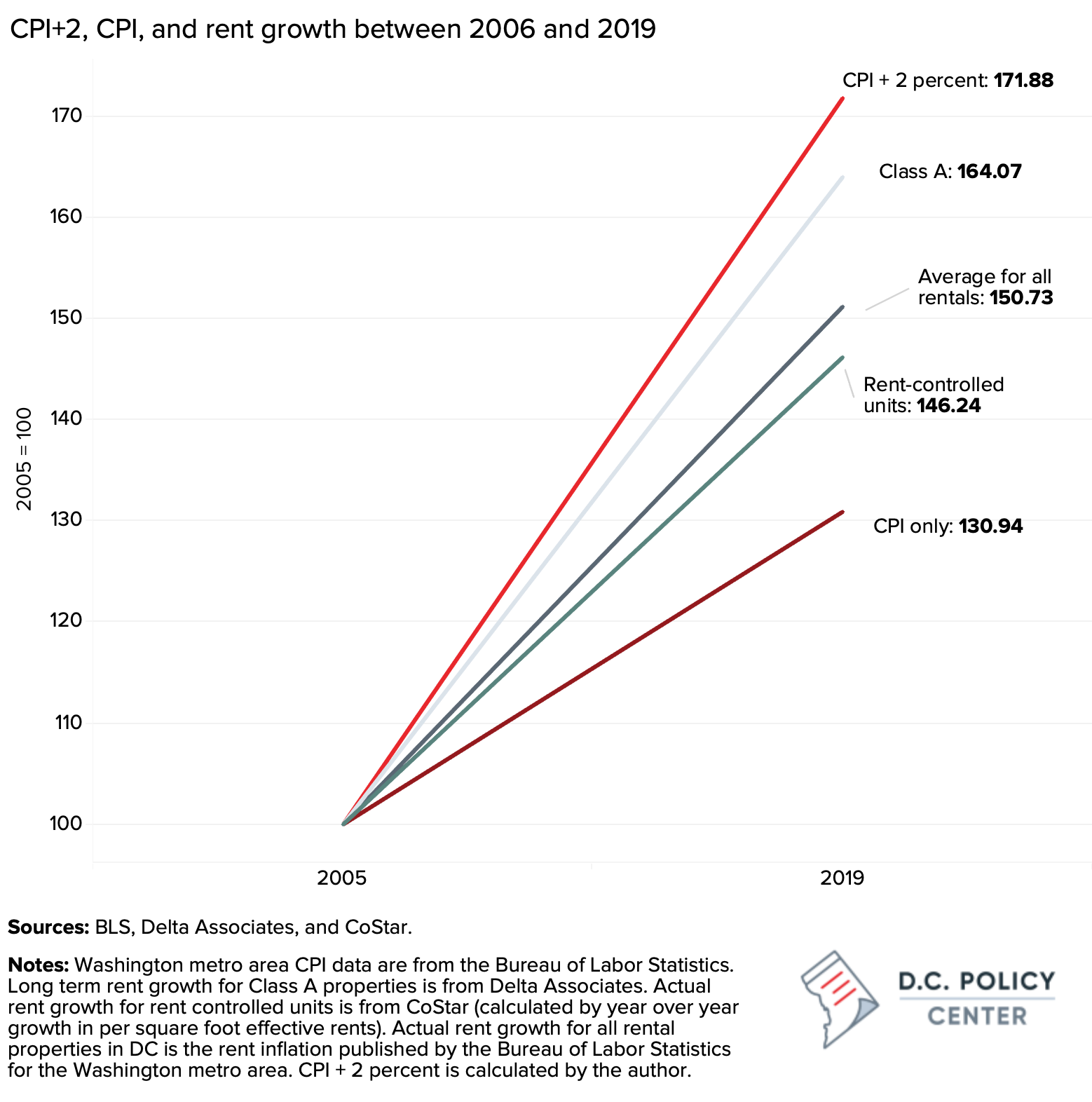

Over the years, the average rent growth in rent-controlled apartments has generally remained under the legislated Consumer Price Index (CPI) + 2 percent cap. Average annual rent growth across all rent-controlled buildings in D.C. between 2005 and 2019 was an estimated 2.8 percent. Had rents grown at CPI+2 percent, as allowed under the current rent control law, the average annual rent growth would have been 4 percent. Average annual rent growth in Class A apartment buildings during the same period was an estimated 3.6 percent.

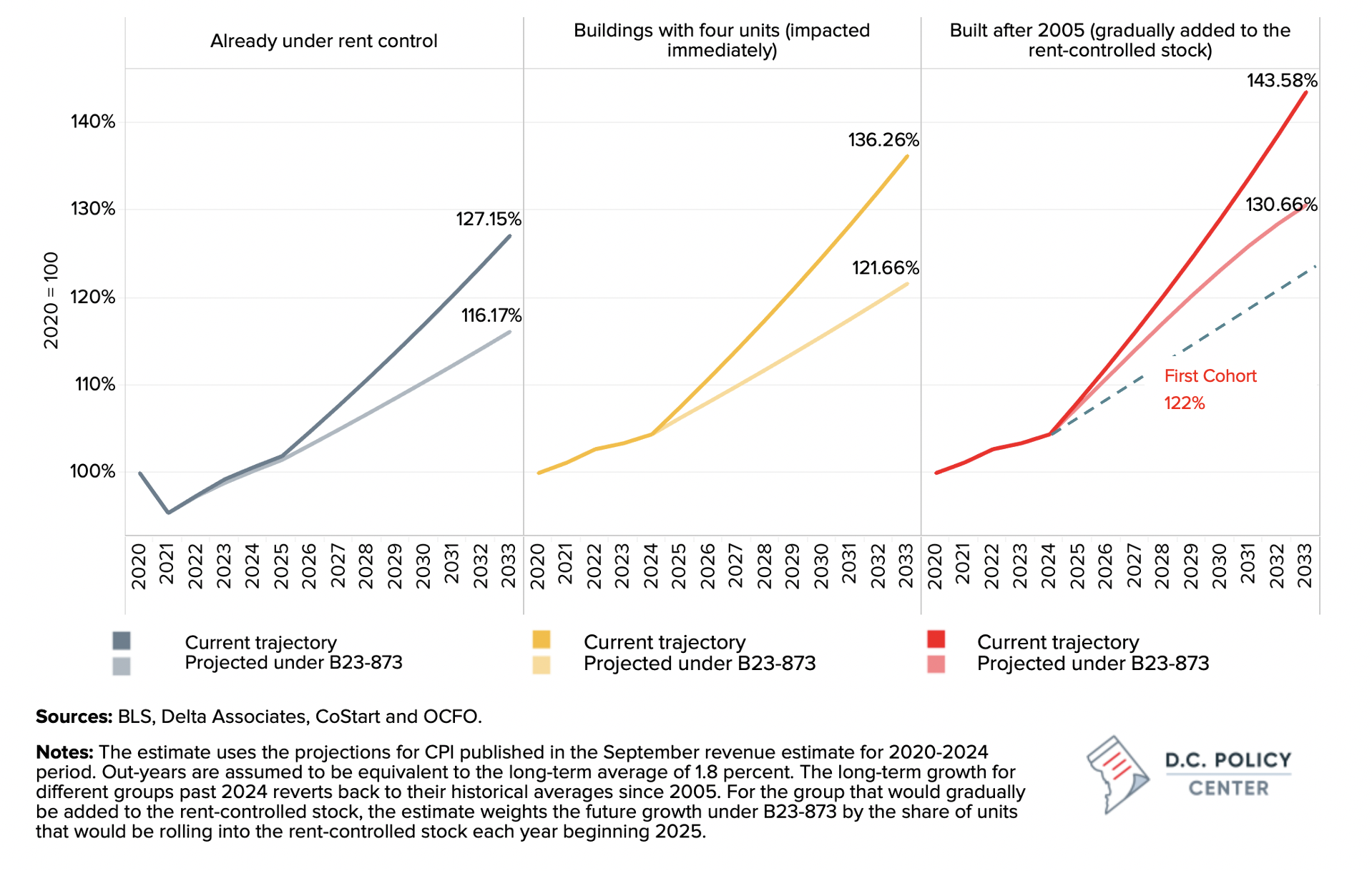

Because B23-873 would remove almost all possible means of raising rents above CPI by (a) eliminating vacancy increases; (b) making it harder to file various petitions; (c) significantly reducing rent increases providers can seek under various petition processes; and (d) limiting landlords to a fixed 30-day period for implementing rent increases each year, the CPI will likely be the ceiling on rent growth. Under B23-873, rents would grow, on average, 0.8 percentage points slower for units that are currently under rent control, if long term CPI remains at the projected 1.8 percent. For units that are not currently under rent control, but would be subjected under B23-873, annual rent growth could decline by 1 to 1.2 percentage points each year.

The immediate impact of B23-873 on rent growth would be muted because the pandemic-induced economic recession is projected to put negative pressure on rents between 2020 and 2022. However, the CPI cap would become binding during the post-COVID recovery. As a result, housing providers who are relying on the recovery to make up for their current losses would not be able to do so under B23-873.

Lower rent growth will reduce net operating incomes, building valuations, and tax revenue.

With limited rent growth, the income generating capacity of rent-controlled buildings would also decline, lowering their value and taxable assessments. Consequently, tax revenue would decline.

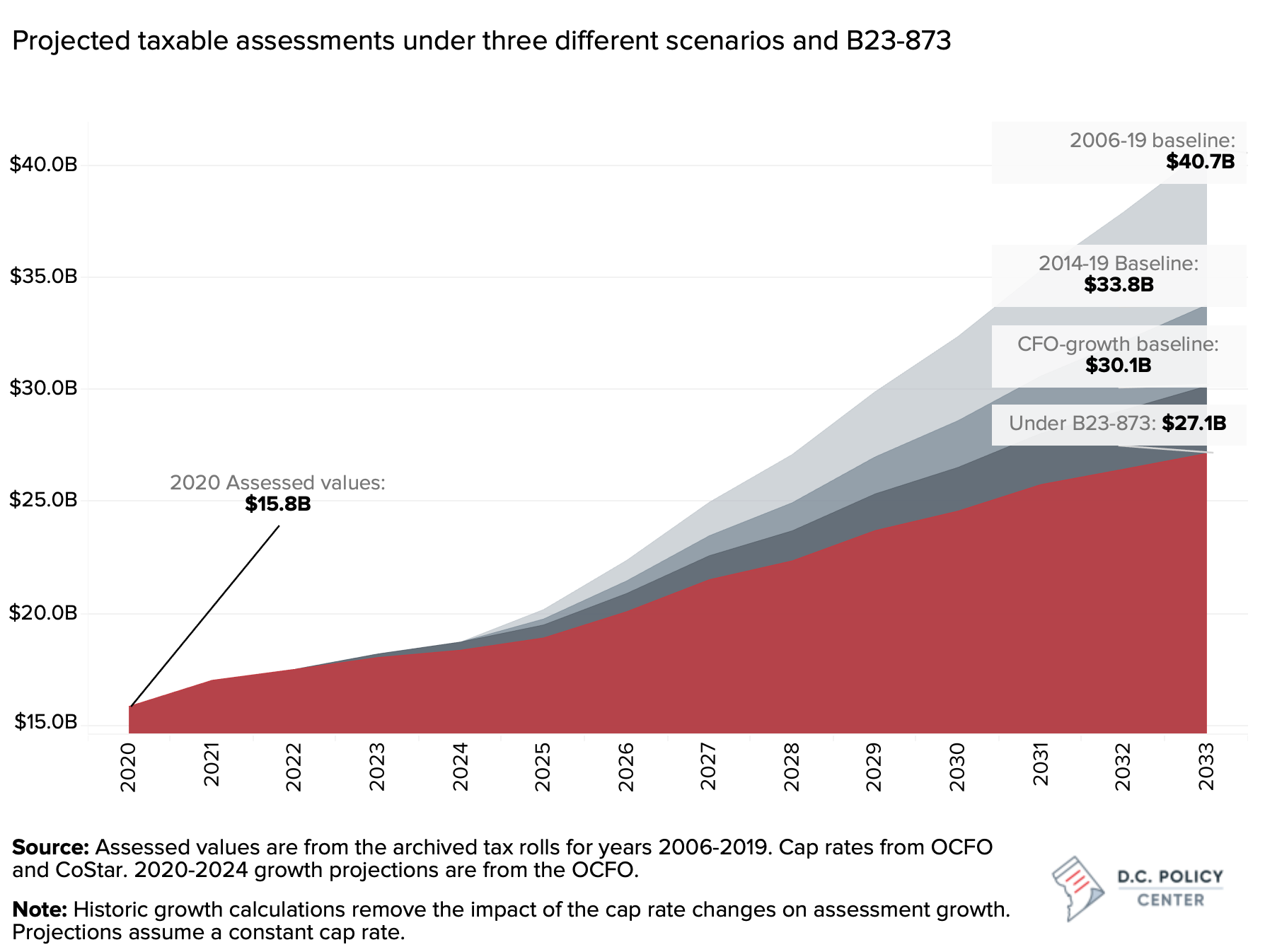

Comparing the projected assessment growth under B23-873 with three different baseline scenarios show that rent-controlled apartment buildings could lose anywhere between ten percent to one-third of their assessed value over the next decade. These losses would grow even faster over time as more buildings become subject to rent control and the impacts of restricted rent growth are compounded.

For this analysis, we built three baseline scenarios: (i) a projection of future assessment growth that replicated the growth patterns among rental apartment buildings during the 2006-19 period; (b) a projection of future assessment growth that replicated the growth patterns during the 2014-19 period; and (c) a projection that uses the estimated real property tax growth in 2024 published in the OCFO’s September revenue certification letter. We then compare the projected growth under B23-873 with these three baselines. We estimated the projected assessment growth between 2020 and 2033 separately for the current rent-controlled stock; large multifamily buildings constructed after 2005, and small, four-unit apartment buildings. This is because these groups have had very different assessment growth histories.

Our projections show that under B23-873, the assessments of rental apartment buildings currently under rent control as well as buildings that would be subjected to rent control, could decline by anywhere between 11 percent to 35 percent by 2033 compared to the baseline scenarios.

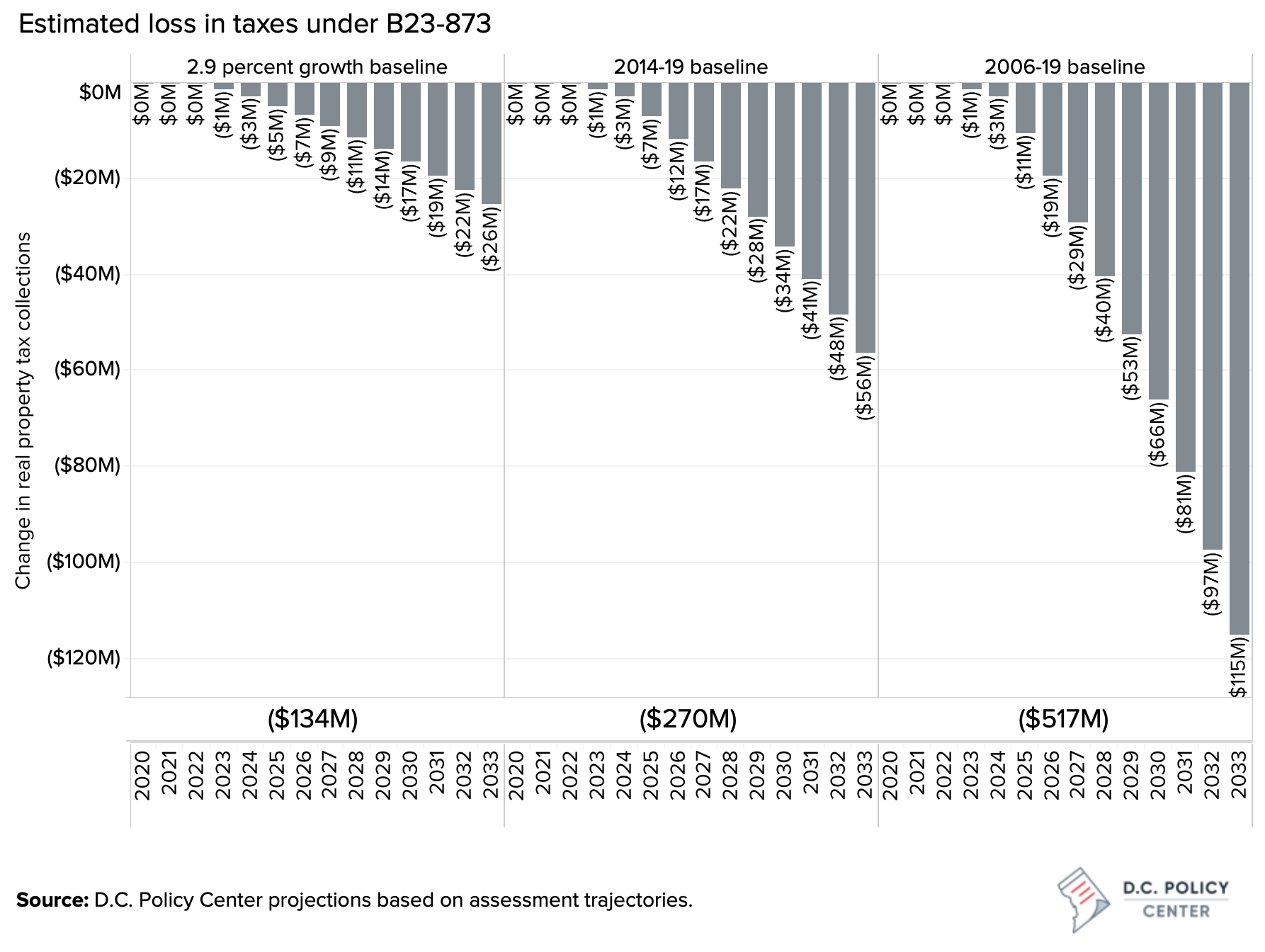

Because the pandemic-induced economic recession itself is putting negative pressure on assessments, the immediate impacts of B23-873 on tax collections may be minimal. But over time, revenue losses would become significant. Even compared to a conservative scenario with a 2.9 percent annual growth in real property taxes (the CFO’s projected growth rate for real property taxes in 2024), B23-873 could cost the District a combined $134 million over the next 11 years. To put this number in perspective, this is greater than the total real property taxes paid by all taxable rental apartment buildings in 2020 (an estimated $112 million). And if the District’s future assessment growth were to replicate its experience between 2006 and 2019 period, Bill 23-873 could depress revenue by over half a billion dollars between now and 2033.

The bill will impact the future of housing by changing the decisions made by renters, housing providers, developers, and investors.

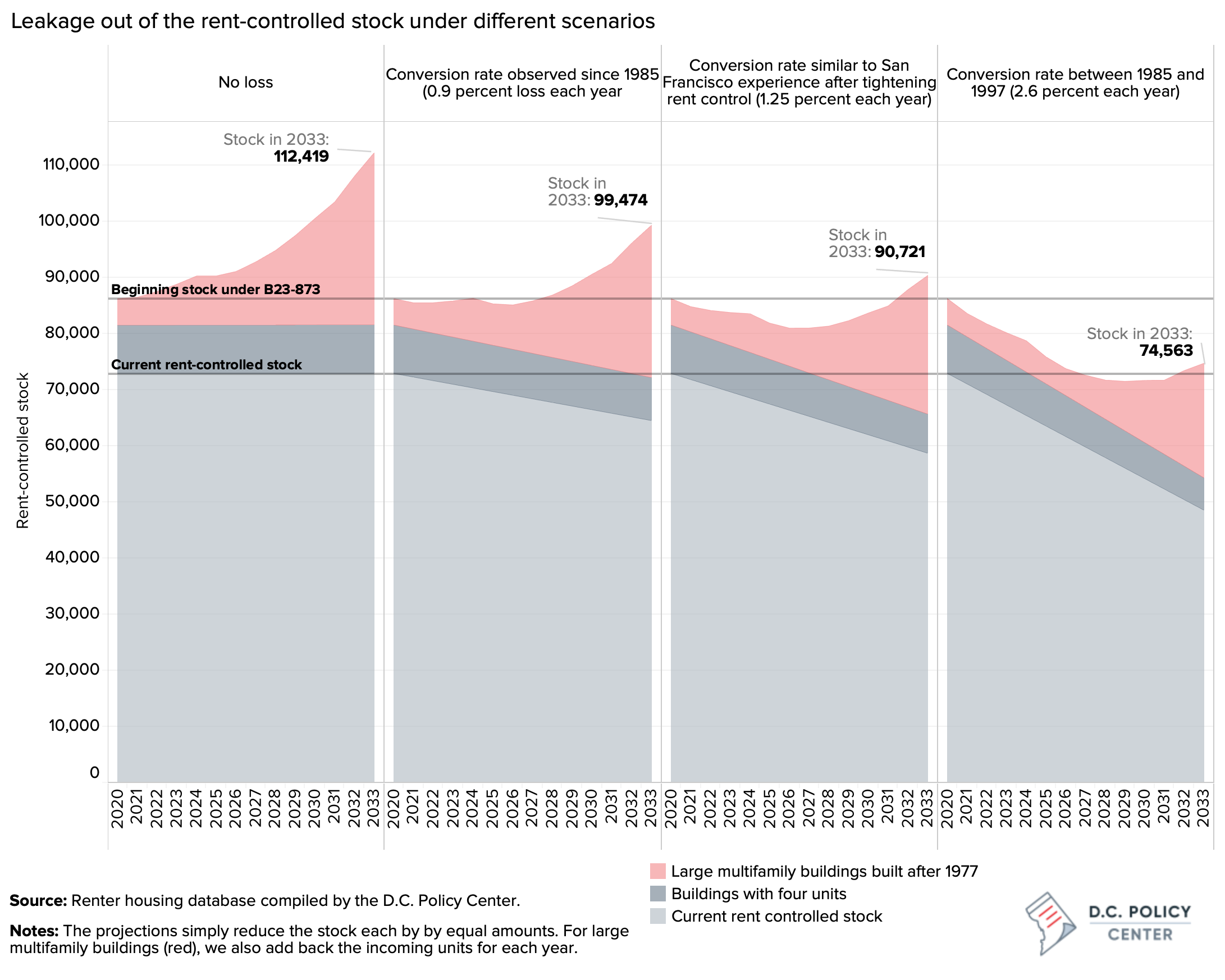

Under B23-873, approximately 112,400 units could be subjected to rent control by 2033. But the actual rent-controlled stock could be smaller.

First, some units could be taken out of the rental market. Limited rent growth and lower returns will likely push some housing providers to convert their buildings into condominiums or co-ops. This has already happened in the District of Columbia. Since the enactment of the Rental Housing Act of 1985, the stock of rent-controlled units declined by an estimated 31 percent. This is the equivalent of an approximately 0.9 percent loss each year. Further, our analysis of apartment building directories published in early 1990s show that much of this exodus happened in the first seven years after the enactment of the bill. As best as we could tell, by 1997, the rent-controlled stock had already declined from its estimated size of 107,000 units in 1985 to under 90,000 units–a leakage rate of 2.6 percent each year.

For example, between 2021 and 2033, if providers were to convert their units from rentals to condominiums at the same rate as observed since 1985, the actual rent-controlled stock could be approximately 97,000 units by 2033. If this leakage rate mimicked what the District experienced between 1985 and 1992, the stock would only reach 74,750 by 2033—close to its current size.

Second, other units may never be constructed. The impacts of B23-873 would also be felt on future development, for example, shifting construction activity from rentals to condominiums, and when condominiums do not make financial sense, impairing future development. These changes will increase the cost of housing—at least for some residents who lose their rent-controlled units—in the District of Columbia, affecting both the development of market rate units and the production and preservation of affordable units.

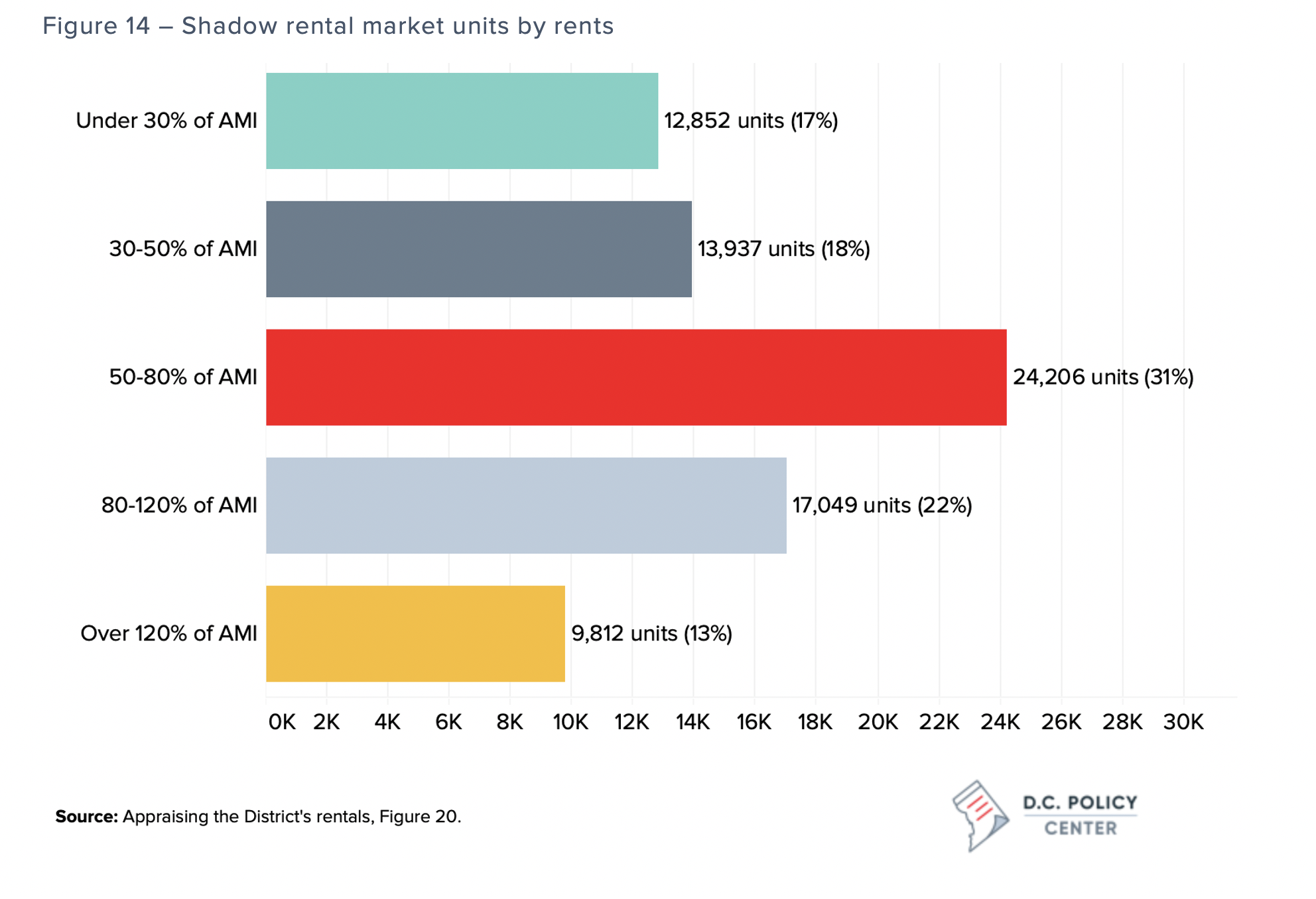

Finally, some lower-income households could see higher rents. Although B23-873 would increase the number of rent-controlled units in the District, and limit their rent growth more severely, rents could end up increasing faster for some households. This is because rental apartments make up only 60 percent of the rental housing in the District, the remainder are in the shadow rental market (which consists of approximately 80,000 single-family homes and condominiums rent by their owners). At present, the shadow rental market is an important source of affordable housing in the city, providing 55,000 units that are within financial reach of households that earn less than 80 percent of Area Median Income. If restricted rents in the rental apartment market reduce availability of rent-controlled units (by reducing turnover, pushing some providers out, or stopping new construction), high-income renters could compete rents in the shadow stock, displacing lower income renters in the shadow rental market.

B23-873 is comprehensive, but its perspective is not broad.

Simply preventing rents from rising will not create affordability in the District’s rental market. Lower rents and returns in rent-controlled buildings will force some housing providers to reduce investments in these buildings and tempt others to take their buildings out of the rental market entirely by converting them into condominiums.

To get renters into units they can afford, the city must first recognize that housing is an ecosystem, and its different parts (rental v. owner-occupied, market-rate v. affordable) work together. Market actors—renters, homeowners, housing providers, developers and investors—respond to policy changes, and their actions collectively shape the housing market. That is, a single policy lever, like rent control, will not operate in isolation and therefore might not be able to bring about the desired policy outcome of getting renters into units they can afford.

The city should make it easier to build new rental units. Rents will grow much slower if there are more rental units, including rental housing for middle and high-income renters. Keeping the District attractive to investors will help continue the housing construction boom that began in early 2000s have added more than 50,000 net new units. More units will be built if the District’s economy remains strong, its population and households keep growing, government services are reliable and the city’s financial management is sound, and if housing policies do not create unnecessary regulatory risk and assure investors of a healthy return on their investments.

Ultimately, the city’s broader perspective for rental housing should recognize that a strong rental housing market relies on convincing a large number of actors to become and remain landlords. These include homeowners who rent out their entire homes, basements or ADUs, or convert their single family homes into residential flats, small landlords of generally older buildings that serve lower income renters, and large housing providers, some with investor backing, that must make a certain return on their investments in order to remain in the market. B23-873, and its companions, ignore these considerations.