This article is a follow up to Exit & Voice: Perceptions of the District’s public schools among stayers and Leavers.

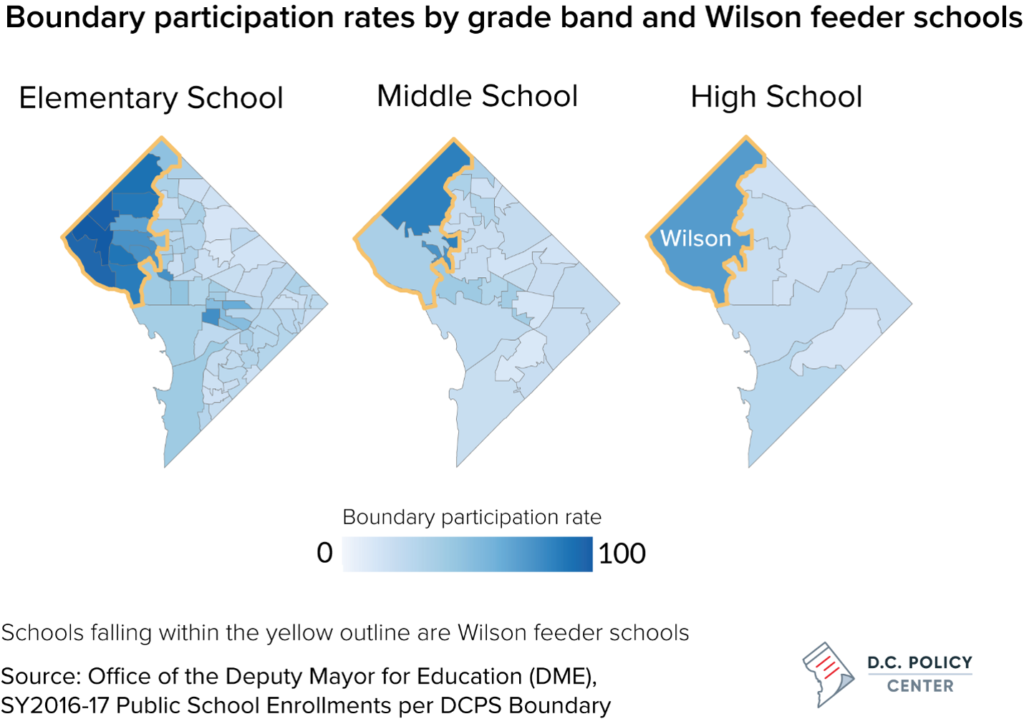

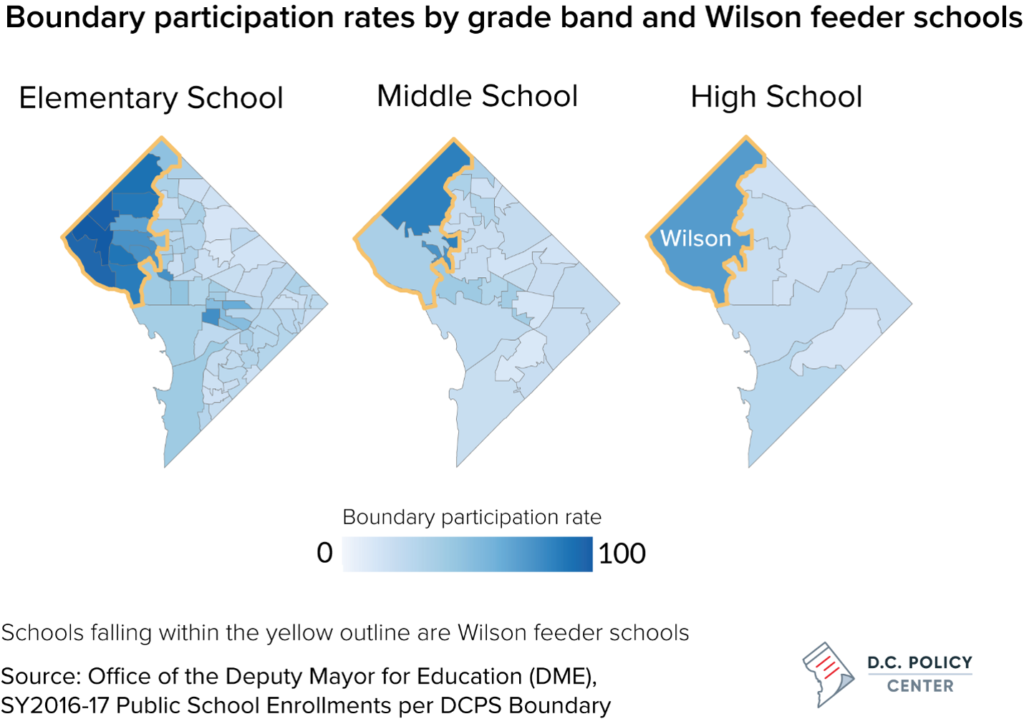

Many of D.C.’s public school students change schools at some point between pre-kindergarten and grade 12, transferring into a different feeder pattern. At the final transition point, which is between 8th and 9th grade, the most popular school-to-school feeder pattern in the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) system is Wilson High School,1 where 54 percent of students in 8th grades of feeder middle schools continue on to grade 9 at Wilson High School.2 All other DCPS high schools have a lower percentage of 8th graders continuing to the 9th grade in their feeder pattern. This is partly due to the popularity of DCPS citywide and application high schools, and partly because public charter high schools draw some 9th graders.

Unlike DCPS, most public charter schools do not have clear feeder patterns for students. Only about 68 percent of 8th graders who attend a public charter middle school have a feeder high school.3 But among some of the largest charter schools (and here we refer to LEAs),4 there are established feeder patterns, and thus feeder retention rates are higher: 70 percent of 8th graders at KIPP DC PCS and 55 percent of 8th graders at Friendship PCS made the transition from grade 8 to grade 9 in their respective feeder patterns.5

A recent Brookings Institution analysis of school choice discussions in a popular online forum found that feeder patterns are mentioned in about one in five posts and are often linked to conversations around residential moves—showing that for some families, feeder patterns factor into school decisions.6 In a regional survey that explored perceptions and satisfaction with DCPS and public charter schools and how parents choose a school for their child, the D.C. Policy Center asked parents questions about the extent to which feeder patterns influences parents’ decisions to choose public schools in D.C.7 We examined these aspects in detail for two parent groups: D.C. parents (particularly those with all children in public schools as stayers) and Leavers (especially those who moved out of D.C. to areas nearby in Maryland and Virginia.

Feeder patterns do not deter parents from choosing D.C.’s public schools.

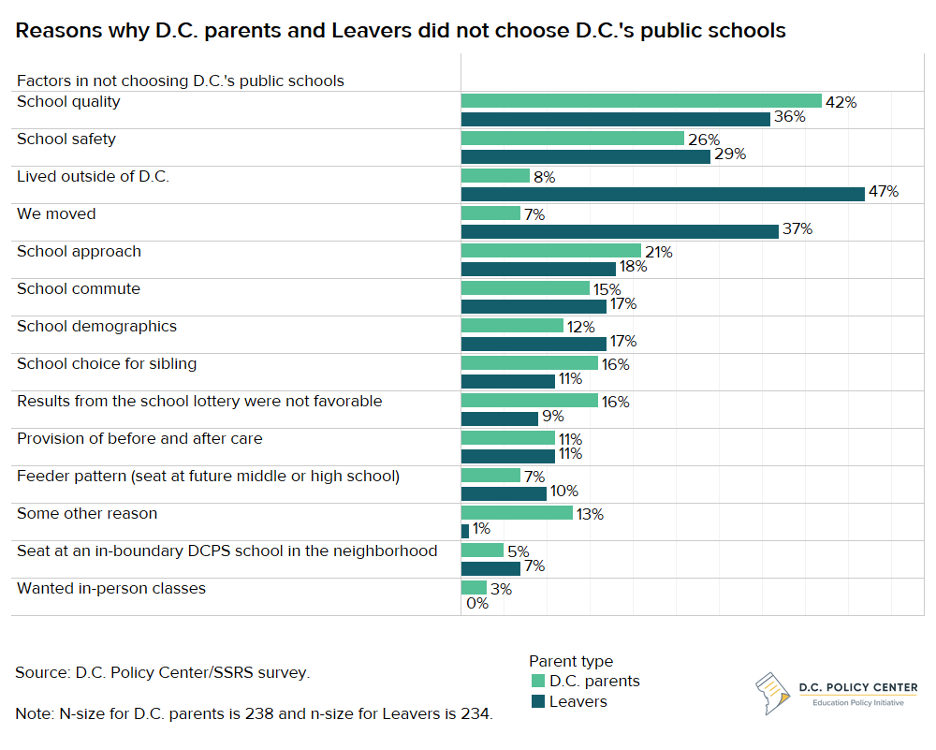

For parents who chose to leave D.C.’s public schools, feeder patterns themselves did not seem to be a major push factor: just 7 percent of D.C.’s parents who did not choose public schools cited feeder patterns as a factor in their decision. By comparison, 42 percent of this group mentioned school quality as a factor in why they did not choose public schools, followed by 26 percent who mentioned school safety. Of the Leavers group who moved to Maryland or Virginia, just 11 percent mentioned feeder patterns as a factor.

However, feeder patterns are also not a factor pulling parents into D.C.’s public schools.

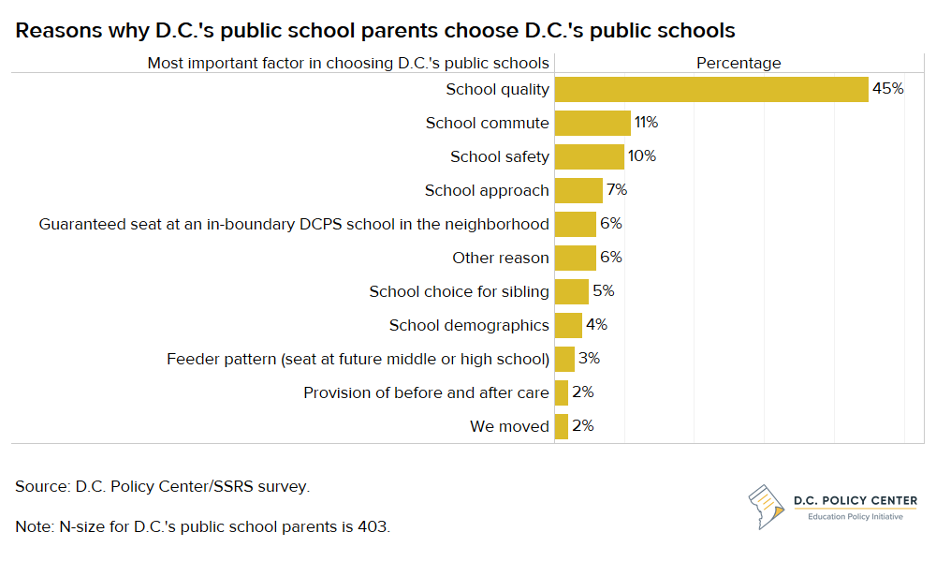

In addition to not being a major push factor for parents who leave, feeder patterns are not a major pull for parents who stay. Just 3 percent of D.C.’s public school parents mentioned feeder patterns as a reason why they chose D.C.’s public schools. Similar to those who left for private options or for schools in Maryland and Virginia, school quality was also the top reason why parents chose D.C.’s public schools (45 percent), followed by school commute (11 percent), and school safety (10 percent).

Many parents expect that their child will stay in D.C.’s public schools but may at some point move to a school outside of their feeder pattern.

While feeder patterns may not have been a major factor when deciding on schools, parents’ satisfaction with feeder patterns may impact exit decisions in later grades. For parents who have children enrolled in D.C.’s public schools, only 55 percent were satisfied with their feeder patterns, compared to 74 percent satisfied with teacher quality, and 71 percent satisfied with communication from the school administration.8

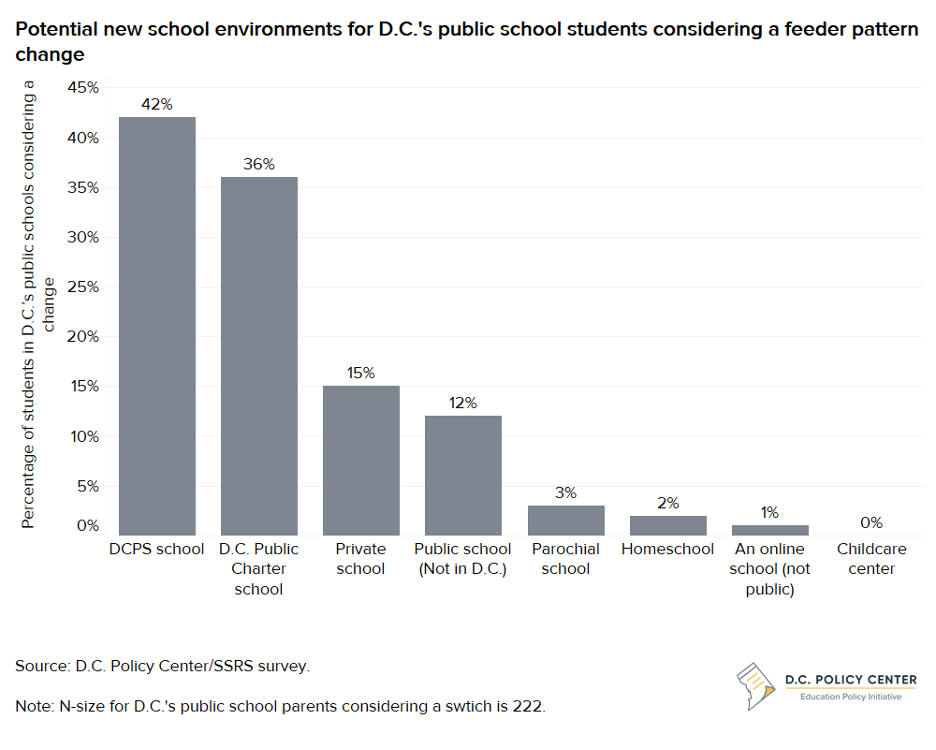

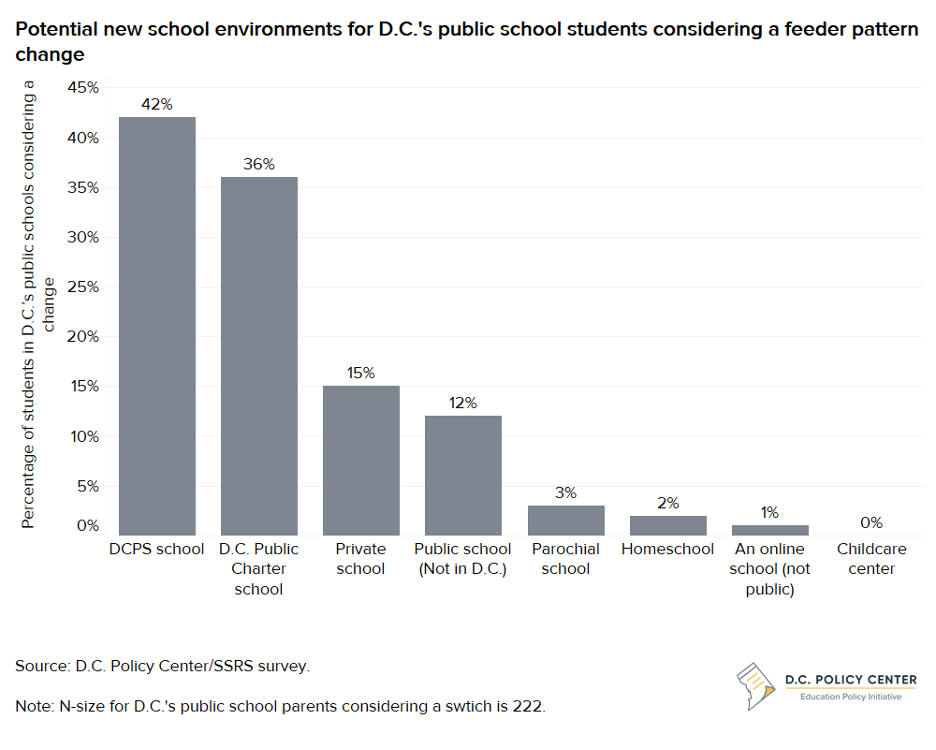

While it is not clear whether parents’ plans to shift feeder patterns are informed by low satisfaction or whether these decisions were planned earlier, we do know that many parents plan to shift feeder patterns over time: Half of D.C.’s public school parents (53 percent) report that they are likely to make a change in the future to a school in a different feeder pattern. Most of these parents (80 percent) are considering another one of D.C.’s public schools, and 27 percent are considering a private school or a public school outside of the District. This suggests that at least half of parents who choose D.C.’s public schools do so with the expectation that they will make a feeder pattern change at some point. When asked why they will make these changes, 47 percent of parents surveyed mentioned school quality, and about one in four parents mentioned transitions to a new school (for example, middle or high school), school location, access to a different feeder pattern, or school demographics.

Despite the attention that feeder patterns receive in some public conversations, surveyed parents seem to consider feeder patterns to be less important than other school aspects like quality, safety, and commute. Even though at least half of D.C.’s public school parents anticipate changing feeder patterns at some point, feeder patterns are not one of the main school-related reasons why parents move out of D.C., nor are they one of the main reasons why parents choose D.C.’s public schools. Looking at enrollment data and movement between schools, feeder patterns might be a minor factor in schools decisions for most parents because feeder patterns are only strong at certain schools with high participation rates (for DCPS in certain parts of the city within Wilson High School9 or for public charter schools like KIPP DC PCS and Friendship PCS, as mentioned earlier). For the majority of students and their families who don’t attend schools with high feeder pattern participation rates or their feeder schools, a high degree of school choice may reduce the importance of feeder patterns, making it something to navigate, rather than a barrier to staying in D.C’s public schools.

Full survey results for other aspect of school decisions and perceptions are available in the full report, Exit & Voice: Perceptions of the District’s public schools among stayers and Leavers.

Endnotes

- Coffin, C. 2018. Schools in the Neighborhood. D.C. Policy Center. Available at: https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/schools-in-the-neighborhood/

- D.C. Policy Center analysis of Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) enrollment audit data for 2016-17 and Office of the District of Columbia Auditor (ODCA) data for the 2016-17 to 2017-18 school years supporting the report, Enrollment Projections in D.C. Public Schools: Controls Needed to Ensure Funding Equity. For more information, visit: https://dcauditor.org/report/enrollment-projections-in-d-c-public-schools-controls-needed-to-ensure-funding-equity/

- Data from school year 2016-17.

- LEA stands for Local Education Agencies, which are individual school districts. In D.C., there are 68 LEAs, including District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) and 67 public charter LEAs that function as independently run nonprofit organizations.

- D.C. Policy Center analysis of Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) enrollment audit data for 2016-17 and Office of the District of Columbia Auditor (ODCA) data for the 2016-17 to 2017-18 school years supporting the report, Enrollment Projections in D.C. Public Schools: Controls Needed to Ensure Funding Equity. For more information, visit: https://dcauditor.org/report/enrollment-projections-in-d-c-public-schools-controls-needed-to-ensure-funding-equity/

- Williamson, V., Gode, J., and Sun, H. 2021. ‘We all want what’s best for our kids.’: Discussions of D.C. public school options in an online forum. The Brookings Institution. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/we-all-want-whats-best-for-our-kids/

- The field work was done in January 2021 and February 2021 in collaboration with research firm SSRS. A representative sample of D.C. parents from all eight wards were recruited through address-based sampling. Leavers living in Maryland and Virginia were identified through survey panels. For more information, visit: https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/school-leavers/

- Coffin, C. and Sayin Taylor, Y. 2021. Exit & voice: Perceptions of the District’s public schools among stayers and Leavers. D.C. Policy Center. Available at: https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/school-leavers/

- Coffin, C. 2018. Schools in the Neighborhood. D.C. Policy Center. Available at: https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/schools-in-the-neighborhood/