COVID-19 has changed migration trends across the entire country, pushing an increasing number of people outside of high-cost areas like the D.C. region, to lower cost, smaller metropolitan areas. When these folks move, do they take new jobs close to their new homes? Or with remote work taking hold, are they moving away but keeping their existing jobs in the region?

Understanding this trend is important because remote work may disguise the extent of the talent shifting away from places like the Washington metropolitan area to elsewhere in the country. With workers gone, but still working their jobs here, the impact on the region’s workforce would not be immediately obvious.

This chart of the week is a publication of the D.C. Policy Center’s Alice M. Rivlin Initiative for Economic Policy & Competitiveness, which provides an in-depth and objective look at the factors that influence the District of Columbia’s attractiveness and competitive position in the region and the nation.

We wish to thank Fort Lincoln Realty Company, Inc., The Kimsey Foundation, Monumental Sports & Entertainment, Quadrangle Development, and Tishman Speyer for their support of the Rivlin Initiative’s work.

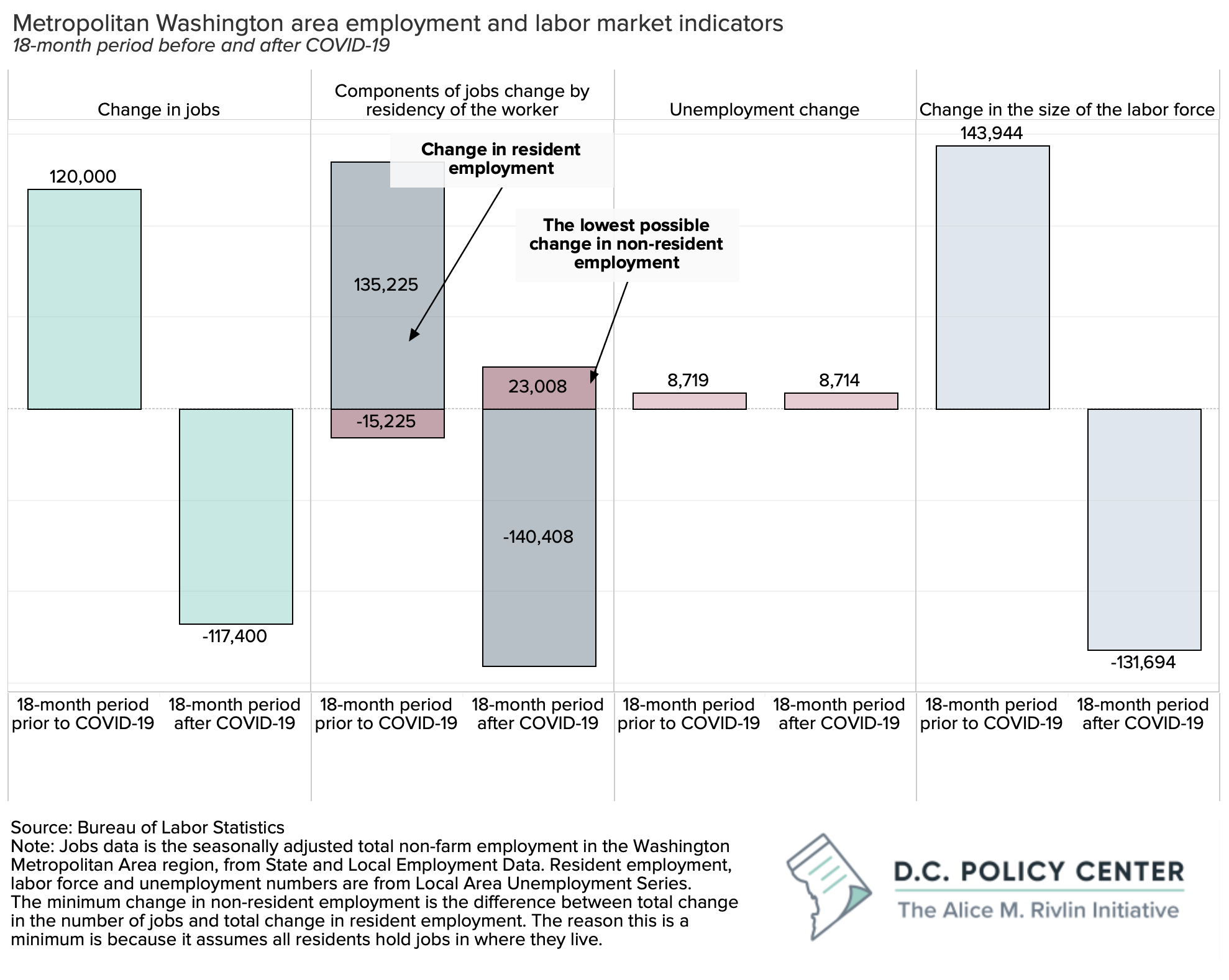

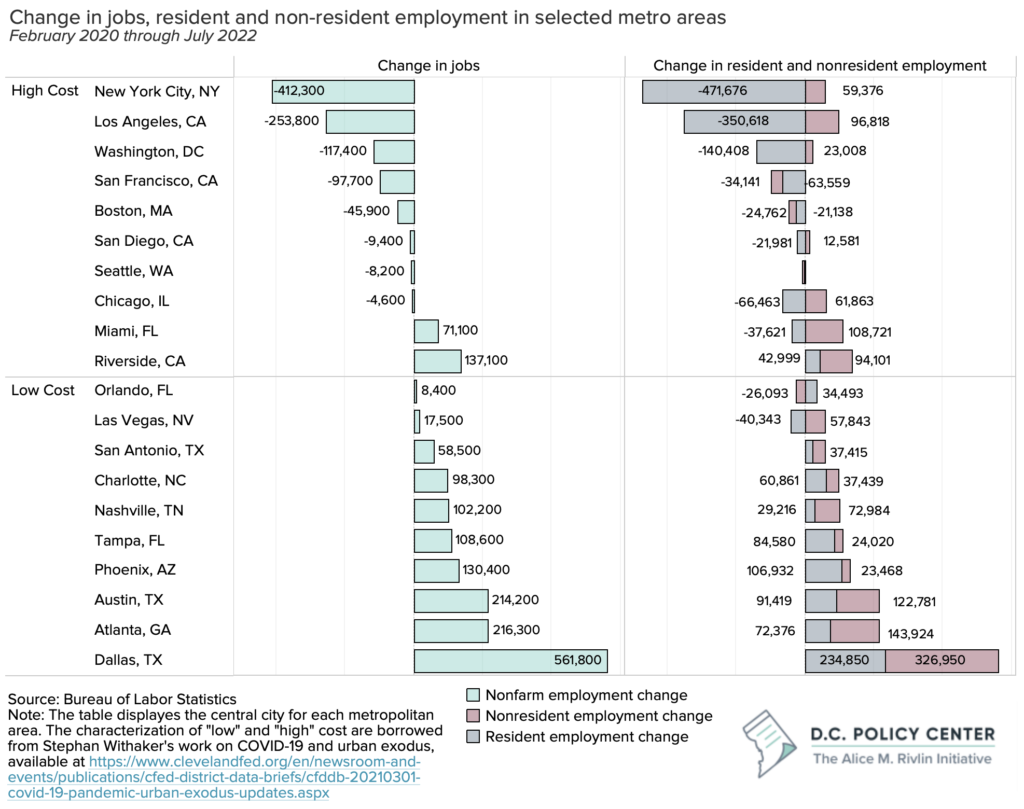

Since the beginning of the pandemic (the 18-month period between February 2020 and July 2022 for which we have data), the Washington metropolitan area has lost 117,400 jobs. During the same period, resident employment has declined even faster, by 140,408. This means non-residents are potentially holding 23,000 more jobs (the difference between the change in all jobs and change in jobs held by residents of the region) than before the pandemic began.1 These jobs might be held by entirely new workers, commuting from nearby places like Baltimore, or they could be held by residents who have left the region, but kept their jobs here.

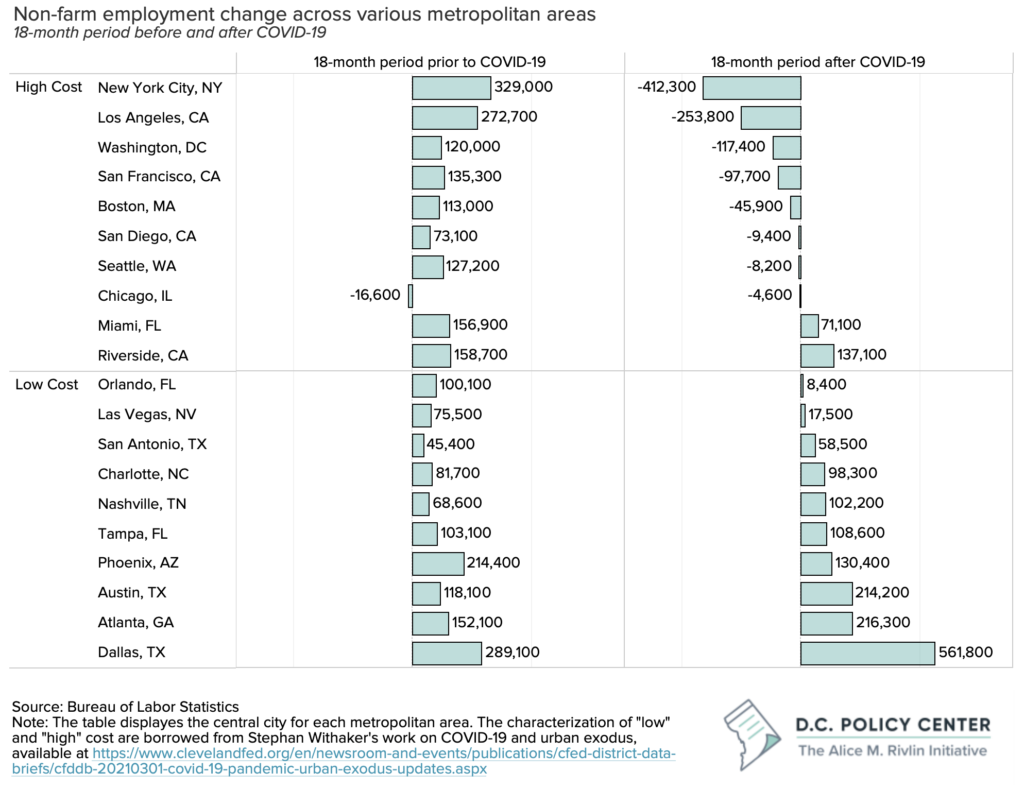

Compare this to the 18-month period right before the beginning of the pandemic—from September 2018 through February 2020. During this time, employment in the region was growing, and resident employment was growing even faster. This means talent was moving to the Washington metropolitan region: some of these new workers came to the region taking jobs previously held by non-resident workers, and some were already working in the region, and decided to move closer to their work.

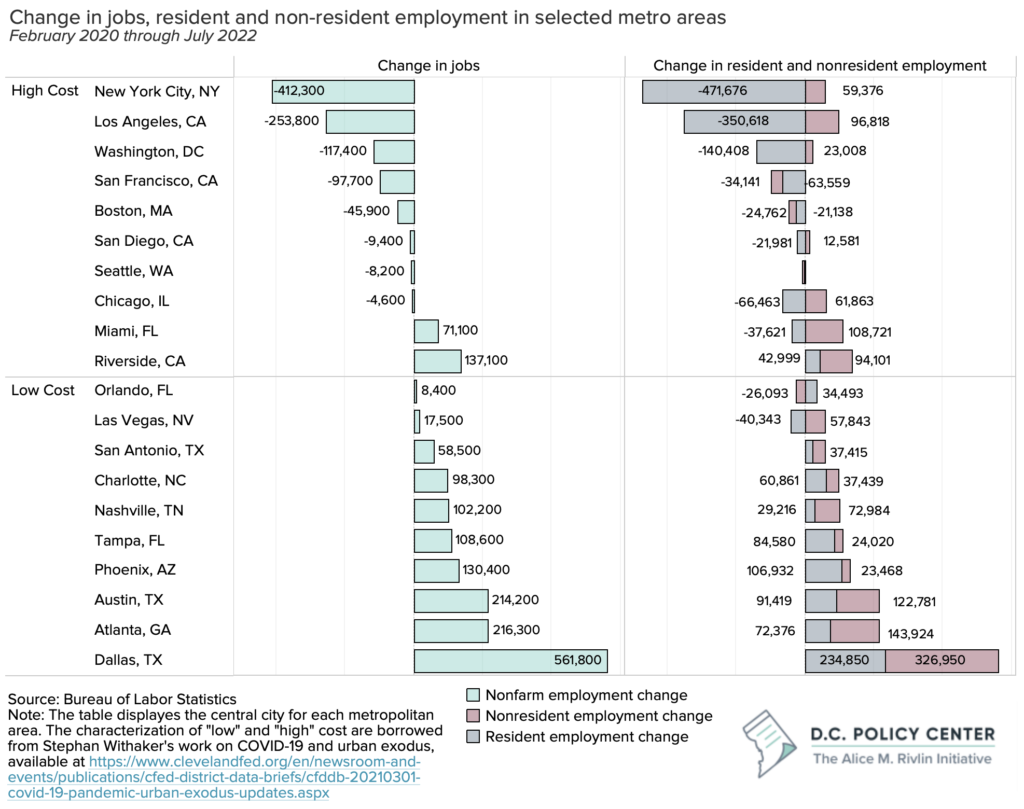

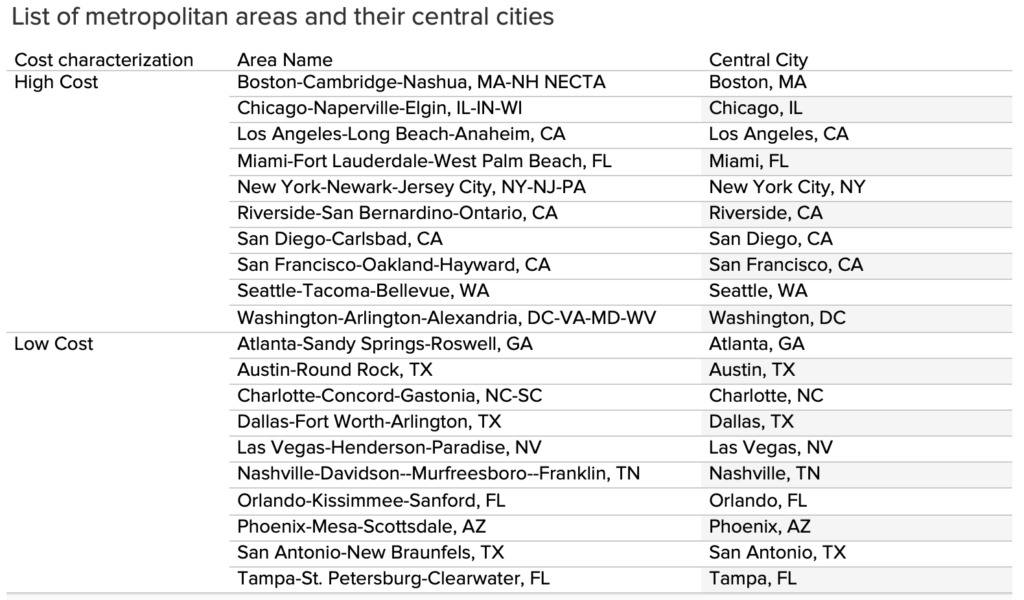

The Washington metropolitan area is not alone in experiencing this trend. Many of the large, high-cost metro areas are losing jobs, with residents leaving at a rate faster than jobs are declining—suggesting that some of these residents are keeping their jobs but moving to new areas. Metropolitan areas surrounding New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and San Diego are also losing resident workers faster than they are losing jobs, and therefore increasingly relying on non-resident workers, some who left these areas but kept their jobs. (And San Francisco, Boston, and Seattle metropolitan areas are losing both resident and non-resident workers).

In comparison, many low-cost, smaller metro areas are experiencing rapid job growth along with in-migration of new workers. However, these smaller metro areas also seem to be relying on an increasing number of non-resident workers to fill open jobs. For example, the Austin-Round Rock metropolitan area in Texas added 214,000 jobs since February of 2020. Potentially more than half of these new jobs are worked by those who live outside the Austin metro region. Similarly, the Atlanta metro area added 216,300 jobs, but only 72,000 are residents of the region including new arrivals, new additions to the labor force, or those previously unemployed. The remaining 144,000 jobs are held by non-residents.

These lower-cost metropolitan areas were growing alongside their higher-cost counterparts prior to the pandemic, but job growth truly took off after COVID-19. Metropolitan areas surrounding San Antonio, TX, Charlotte, NC, Nashville, TN, Tampa, FL, Austin, TX, Atlanta, GA, and Dallas, TX added more jobs in the 18 months immediately following COVID-19 than in the 18-months immediately preceding it. And they are increasingly filling these jobs with non-resident workers. It is possible that these areas are seeing population and housing growth right outside their official boundaries (as defined by the Office of Budget), and if this is the case, these workers may become reclassified as resident employees when the OMB redefines metropolitan area definitions, as it often does).

Next week, the D.C. Policy Center will publish a deeper dive into how population changes throughout the pandemic have influenced labor market and housing trends in these metropolitan areas. By comparing the changes in a few key recovery indicators across high- and low-cost places, we can see which regions have emerged from the pandemic as more economically competitive. It is possible that out-migration from high-cost, large cities will slow, remote workers will settle, and the impact on the labor market in regions such as the D.C. metro area will be a one-time observation rather than an emerging trend. However, there is also a risk that workforce dynamics will permanently shift to the region’s detriment. Given this risk, a close study of regional workforce dynamics will be important as these challenges present an opportunity for the District to refocus workforce and economic policy to match the realities of the region.

Technical notes

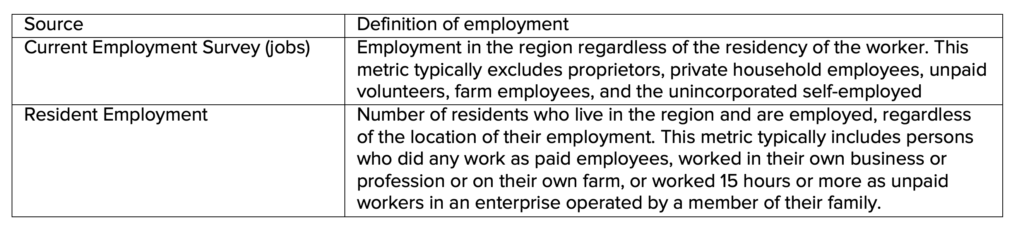

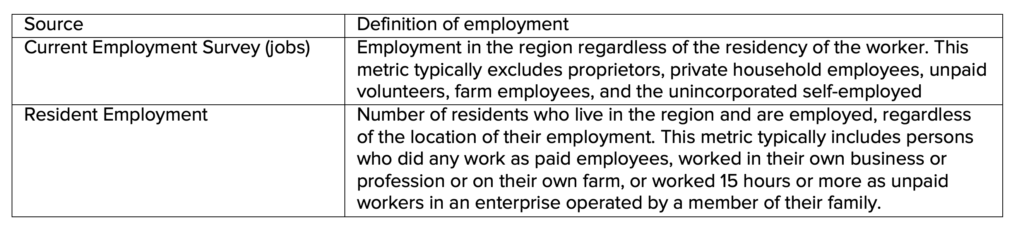

It is important to note that the methodology we use here provides a sense of direction of talent moves, but it also has problems that prevent us from getting to reliable numbers. Specifically, the jobs numbers and the labor force numbers come from two different sources (the first, from the Current Employment Survey, and the second, from the Current Population Survey) that measure employment in slightly different ways as described in the table below, and are subject to errors that are present in every survey. In the Washington metropolitan area, for example, in 2021, there were potentially 180,822 workers who would be counted in the resident employment figure but not in the jobs numbers (ACS 1-year data summary for 2021). But that number increased by only 2,171 between 2019 and 2021. Since our estimates are comparing changes, and not levels, we don’t believe that the definitional differences would make a big enough impact in our analyses to reverse the direction of the change.

We will have to wait for various data releases by the U.S. Census to truly understand the impact of remote work on the local talent in the region.

And the prevalence of remote work will require rethinking job location characterizations in various datasets. With more people working from home, the self-reported “place of work” variable used in the American Community Survey has become increasingly noisy. Similarly, various other data sources like Quarterly Workforce Indicators, Longitudinal Employer-Household dynamics, or Origin-Destination Employment Statistics, which partly depend on employer-reported job locations, may become more challenging to interpret.

The characterization of high-cost an lower-cost metropolitan areas was inspired by the data presented in researcher Stephan Whitaker’s paper “Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Cause an Urban Exodus?”. The high-cost areas include metropolitan areas with populations greater than 2 million and top-quartile median for-sale home list prices per square foot. The lower-cost metro areas are regions that with high net migration from large, high-cost metro areas and are only considered low-cost relative to the high-cost metropolitan areas.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Norton Francis for his valuable comments and insights.

Appendix

Endnotes

- This is a rough estimate, since the employment and labor force data come from two different sources. See the technical note at the end. It is also a low-end estimate, because the calculations count resident job losses towards regional employment losses. Some of the residents lost possibly worked in places outside the Washington metropolitan area. Their departure from the region will be counted in the labor force data but cannot be counted towards the job loss numbers, increasing the gap that must be filled by non-residents.