The nonprofit and advocacy sector in the District of Columbia employs over 70,000 employees.[1] While some of these organizations are focused on national policy, local nonprofits play an important role in service delivery—from out-of-school time programs, to community collectives providing services to the most vulnerable residents.

The D.C. Policy Center implemented a questionnaire between March 19 and March 25, 2020 on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the region’s nonprofits. The questionnaire was distributed through various channels including foundations, grant-making organizations, and nonprofit networks. This write-up highlights some of the key themes that emerged in the responses, along with external data on the nonprofit community where available. Please note that the findings from this questionnaire are qualitative and should not be viewed as representative of the experiences of nonprofits in the region.

Main themes

- Nonprofits see a greater need for their services both in the near term and throughout recovery, but have fewer means to meet these increased needs. They emphasize that the government and other philanthropic organizations must do more to ensure that resources in their issue areas are not cut back.

- Nonprofits worry that their organizations and other nonprofits would be financially harmed in ways that would make it difficult to come back during recovery. Many nonprofits had to cancel events and fundraisers during what is generally a busy fundraising season. Some have lost other revenue sources (closing of retail activities such as thrift stores, and cancellation of revenue generating programs or cancellation of contracts), and do not have the means to build a different revenue model. While most nonprofits appear to have a staying power of at least three months, many (correctly) foresaw that the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic will last much longer.

- Nonprofits quickly acted in response to the pandemic, but do not appear to have a long-term strategy. Many nonprofits switched to online services and remote work; changed the way they interact with their clients but are not confident that the “virtual” model can be sustainable.

- Nonprofits that provide digital literacy training and computer access have found the shift to virtual environments a particular challenge. “Our students, by definition, need basic computer skills and most do not have computers at home,” one wrote.” Ideally, we could offer on-line instruction given our team of dedicated volunteer instructors. However, we do not have enough donated computers to refurbish and provide to students. … [A] grant to purchase either low-cost refurbished computers or much less expensive Chromebooks would help fulfill the need.” Another respondent said that they were most concerned about “isolated, lonely, depressed seniors” during this time of shutdowns and social distancing, “and trying to find the effective way to contact them, since many of them are not using technology.”

- Some quickly found that regulatory barriers (online privacy laws, telemedicine regulations among others) and lack of access to technology further impaired their work.

- Nonprofits predict that the crisis will expand inequities in the District. A great many of them are worried that their clients are facing a greater degree of danger from COVID-19. They also raised concern that if the government budgets are cut in face of falling state and local revenue, these cuts would further worsen the life outcomes of their clients and the most vulnerable residents in their jurisdictions.

Immediate response to COVID-19 crisis

We inquired about the immediate actions nonprofit organizations took in response to the COVID-19 crisis. The respondents were provided a set of actions and were asked to choose those that would best describe their immediate response to the COVID-19 pandemic. They were also given the opportunity to add a free response. We also inquired how nonprofits shifted their operations in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We summarize the findings below.

There has been a swift shift to telework and mode of delivery has changed for many organizations. Most of the respondents said that they moved to telework immediately. Along the same lines, many organizations mentioned that they have changed their mode of operations, sometimes entirely closing their physical locations, and sometimes eliminating walk-in services, to adjust their protocols to minimize health risks. A notable share of the organizations had moved some services online, but many reported that they were still trying to figure out how to adapt to the new conditions.

One respondent wrote, “We are serving some clients through video conferencing and email. We provide legal services to low-income clients so technology access [is] still an issue for them. Clients are still able to drop papers off etc. We have cancelled most of the new client appointments and [are] only servicing existing clients.” Many respondents who provide direct services also noted that they are more engaged in advocacy.

“We have moved all staff to telework, and we’ve reduced our core working hours to 10-3 to give staff flexibility to manage their own health and well-being,” another nonprofit wrote, noting that “Many staff have young children at home and are finding it difficult to work a routine 8-hour day.”

Some nonprofits also said that some of their previous services are no longer deliverable, and they have shifted to new supports—for example, shifting from student services to at-home supports, such as grocery deliveries, or moving from home-visits to virtual meets for wrap-around services. “We have suspended all regular after school and adult programming and are instead focusing right now on contact-free food and diaper distribution, along with sending students tailored learning packets and figuring out a way to do virtual tutoring,” one nonprofit respondent wrote.

“We have gone 100 percent virtual, serving our students remotely,” another organization told us. “We are providing webinars and Google classroom workshops as well as one-on-one coaching. We are helping them deal with online learning challenges, apply for SNAP benefits, get home from studying abroad and from college, and with the mental health issues due to this epidemic as well as with the derailment of their college dreams.”

Many nonprofits engaged in healthcare made a swift shift to telemedicine but have also struggled with regulatory barriers and an overall reduction in funding. “We will look into teletherapy, but only two of our programs are eligible,” one provider said.

“DC government has done a lot of helpful things so far,” another respondent wrote, including “changing payment expectations for our homeless services to ensure that telephone visits ‘count’ for payment. They have also changed Medicaid regulations to allow for telehealth as billable visits. We will need some financial assistance, however, to help us meet gaps, especially depending on how long this situation continues.”

Similarly, education providers are trying to figure out how online education can be conducted given the requirements of federal legislation such as the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), which applies to how companies collect personal information online from children under age 13, and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), which addresses how personally identifiable information about students is used, stored, and disclosed.

Volunteer programs have been cancelled or reduced significantly to reduce the risk of transmission. Half the respondents have reduced the number of their volunteers or entirely cancelled their volunteer programs. Among those, the hardest hit organizations are those primarily engaged in organizing volunteers. One nonprofit wrote that their biggest concern was that one of their volunteers would contract the virus, noting that the “age of our volunteers creates a critical vulnerability,” as many volunteers are older or retirees.

A small number of organizations have replaced their volunteers with contract workers or staff to reduce the impacts while limiting exposure of volunteers to potentially dangerous situations. One organization mentioned that they even stopped taking certain types of donations such as unpackaged food to reduce contamination risks.

Many organizations reduced hours of operation, and cancelled events or programs. A notable share of the respondents reported that they have reduced hours of operation, which is linked to their need to cancel programs. Some have been able to shift operations online, or increase services provided when needed, but others have had to cease operations entirely. For example, many out-of-school time providers and other providers of onsite, in-person services had to entirely close operations. Some respondents operating in the criminal justice and legal aid space have stopped taking new cases. In housing, providers report the challenge of continuing wrap-around services for residents as they serve.

Along with these changes, organizations are doing everything they can to contain costs. Some reported furloughs and staff cuts; many cut back non-personnel costs by not purchasing supplies, or cancelled orders or contracts with vendors. A small share of respondents had delayed payment of bills. “Cash flow/operating reserves are the biggest issue for our organization,” one respondent wrote. “We are concerned that since we have had to cancel programming, we will need to return restricted grant dollars while being unable to bring in additional revenue. As a result, we anticipate that we will need to reduce pay and/or furlough employees.”

Many organizations are facing revenue losses because they had to cancel fundraising events, close retail stores (such as thrift stores) or lost contracts. These concerns arise repeatedly, and loss of revenue was among the largest risks nonprofits are facing among this group of respondents. “We see our donations stream as our biggest risk to the organization,” one nonprofit wrote. “If donors decide to delay anticipated donations, or freeze new donations, this could drastically effect our operations.”

Risks and concerns

We inquired about what the respondents see as the biggest risk or consider as their greatest concern during the pandemic.

The top concern or risk among the respondents is the fiscal future of their organizations. One of the most common concerns of the respondents who answered this question was that the closures will likely be a big fiscal shock for their organizations. They are mostly worried about loss of donations because of the impact of the crises on their donors, loss of revenue due to closures, loss of revenue because they had to cancel fundraising events, and loss of revenue because they would not be able to meet grant expectations from their current donors. The respondents also noted that they see a shift in donor or partner priorities that could create more fiscal risks.

Separately, we inquired about the revenue sources nonprofits rely on. The most common source of funding for the respondents is state and local grants and contracts. This might be a feature of the group, as the respondents included a large share of nonprofits who are direct service providers and who are engaged in education, which typically relies on government grants.

Earned income, which has been identified as a key risk factor, is the second largest source of revenue for respondents: Half of the nonprofits that responded to the survey normally derive at least a third of their revenues from earned income and ten percent of their revenues from events. One respondent wrote that lack of funding was a major concern going forward, as “donations and grants make up 70 percent of our budget and we had to postpone annual gala which normally covers 10 percent.”

Respondents were also concerned about organizational and staff risks. Many are worried about the impact of the crises on staff morale and staff health. Those serving in areas of human services, housing, homeless, and health were more likely to mention this concern. This was particularly an area of concern for those organizations that rely on a volunteer base, as they did not want to expose their volunteers to additional risks. These concerns are compounded by fiscal difficulties as many organizations noted that staff could be demoralized if they expect their paychecks will shrink or disappear in the coming days.

Organizations expressed concern that their presence in the community will diminish, undoing years of work they have done. One service provider wrote, “If this goes on for more than a month or so, without help, we won’t be able to get restarted. I’m also worried about the staff and if they will return.” Looking beyond the immediate impacts of the pandemic, many also worried that in areas they serve, budget cuts will amplify the impacts over the years. This was a very common concern of those serving in the education and housing spaces.

Finally, respondents also cited their concerns regarding their clients and the communities they serve. Many organizations are worried about increased stress on their clients, and the risk of contracting the disease. “We are concerned about food supplies and having enough to meet the needs of the community,” wrote one nonprofit that had dramatically increased its food distribution. “We are concerned about having enough grant funds to provide direct assistance in the form of rent/utilities as our demand spikes.”

Several nonprofits noted that among the communities they serve, underlying health problems increase the risk of fatalities. One wrote that their main concern was “maintaining the health of our patients; keeping them safe and also out of the ER.” Many also worried about the children in unstable living conditions will be further harmed. Nonprofits also mentioned that among groups they serve, disruption of services will lead a to permanent decline in clients, especially in areas where client engagement was difficult in the first place, such as homeless and mental health services.

Expectations from the government

We inquired about the government interventions that could help support the nonprofits. The question was framed as supports from the District (and other state and local) governments.

Nonprofit respondents most frequently expressed their need for financial support from the government. Respondents commonly noted that the government can help most directly by providing grants and financial support. Nonprofits also mentioned that flexibility on their deliverables under government contracts, and relief from obligations would also help them get through this period. For example, one respondent wrote that their organization would benefit from “loosened restrictions on government grants and issuing advanced payments (rather than reimbursing expenses),” as well as “[no-interest] loans to fund essential expenses.”

Respondents also said they need the D.C. government to maintain budget levels in areas they work on. They expressed worry that additional budget cuts would further impair their work. Other areas of government service that were mentioned were expanding the availability of free internet service, and cutting down on red tape.

Many respondents also said they need the government to step up and be an advocate for the nonprofit community. These include a specified quarantine location, if necessary, and guidelines on crucial in-person services such as childcare. Nonprofits also noted that government support as a guarantor for loans, and legislative changes that incentivize charitable giving, could be of great use to them. Some nonprofits emphasized the importance of leadership from the government in providing guidance in their areas of work.

One respondent also highlighted the importance of a partnership between the government, business leaders, and the nonprofit sector in developing a recovery plan, including “developing VERY CLEAR guidelines about how to handle a second wave. It seems like there is some chance this could hit again in the fall, and shame on us if we don’t figure out better ways to handle it.“

Expectations from philanthropic organizations

The survey also inquired about what kinds of actions from philanthropic organizations can best help them through the COVID-19 crisis. The needs from the philanthropic community centered around financial support for organizations, financial support for the clients, and increased leadership.

Nonprofits need philanthropic organizations to keep their current commitments, relax rules around giving, and provide emergency relief. The most frequently mentioned support that respondents requested from philanthropic organizations is to convert restricted program grants to unrestricted grants. The second most common request was emergency relief. Nonprofits also said that they would want clear indications from grant-making organizations that they would honor existing commitments. Many said that a simplified grant application process would also be helpful.

Nonprofits want philanthropic organizations to increase supports for their clients. Some nonprofit respondents said that gift cards and financial assistance for their clients would be helpful, as well as supplies. There were specific requests for the philanthropic community to increase funding for virtual programming and critical research. Nonprofits also noted that funding for supplies for their staff would help them continue serving their clients.

Respondents were also clear that this is not only a short-term crisis. “From a philanthropic perspective,” one respondent said, their priority was for funders to be “working to understand the immediate needs, as well as planning for the long-term needs. We don’t know what this will look like in three, six, [or] nine months and the true impact that it will have. As much as money needs to be moved immediately, we are in this for a long haul, and funders will need to plan for that/balance that.”

Nonprofits want philanthropic organizations to serve as leaders. Over a quarter of the respondents asked philanthropic organizations to share resources and increase coordination. They also noted that philanthropic organizations should serve as advocates for increased giving by creating funding channels and marketing funding channels.

“Nonprofit networks and foundations could greatly assist us by connecting us with additional funders,” one nonprofit wrote, especially “individual donors and foundations, who may be able to provide emergency response funding or in-kind donations of critical supplies (i.e. hand sanitizer, toilet paper, etc.)” They added, “Nonprofit networks could also connect us with opportunities for our families to access food and other resources within their neighborhoods.”

About the data

In mid-March, the D.C. Policy Center shared a questionnaire about how nonprofit organizations are responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. These questionnaires, distributed primarily through existing nonprofit networks, issue-based groups, and other existing networks by email, were not meant to be representative surveys. Instead, they were an opportunity for area nonprofits to tell us, in their own words, their concerns about their future in an uncertain economic and public health environment.

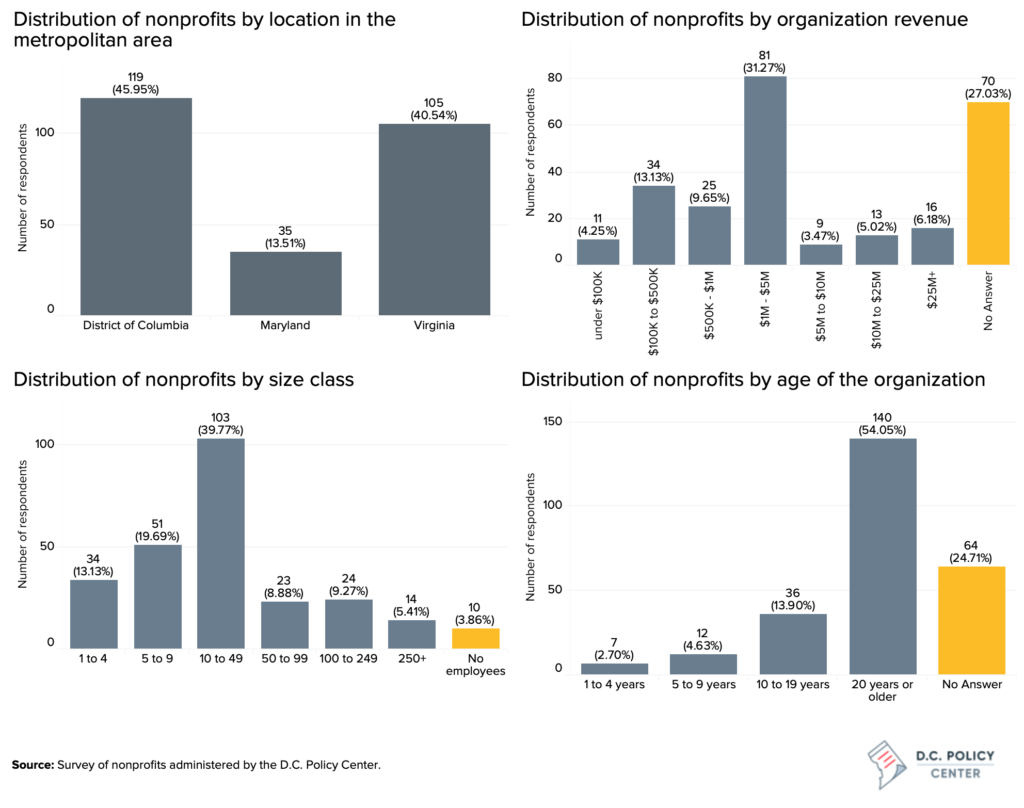

Overall, 259 organizations completed the questionnaire (with acceptable rates of omissions and errors). Of this group, a majority were in D.C., followed by Maryland. The most common nonprofit size was between 10 and 49 employees (40 percent), and the majority had fewer than 50 employees overall. The most common annual revenue category was between $1 million and $5 million (31 percent), although an almost equal share (27 percent) did not share their annual revenue amount. Most of the nonprofits that responded to our survey were older entities, with over half reporting that they have been operating for at least 20 years.

Nonprofits focused on human services and education constituted the largest share of respondents, although respondents could choose more than one focus area or self-describe their issue areas. Among those who self-described, economic security and housing were the most frequent responses. It is important to note that these areas also overlap with human services, so others engaged in this area might have noted “human services” as their focus.

Share your experiences

Going forward, we will continue to work closely with nonprofit organizations, business leaders, community groups, foundations, partners in the D.C. government, members of the Council, and others deeply involved in the District’s response to this crisis. If you would like to learn more, or would like to collaborate in these efforts, please contact Yesim Sayin Taylor at yesim@dcpolicycenter.org or leave a voicemail at (202) 202-2233.