The Washington region today seems unimaginable without Metro, but the system we have today was hardly inevitable.

Initial proposals for a subway system date back to the FDR administration, when the federal government’s expansion during the New Deal and World War II led to an increase in the District’s population. It still took another four decades before Metro’s first segment—the downtown portion of the Red Line—opened in 1976.

The path to where we are today was a long one full of characters with their own visions—some more pragmatic than others—on how to connect the Washington region. Here are the D.C. transit systems that could have been.

The early days

Starting in 1938, a Smithsonian biologist named Waldo Schmitt spent several decades pushing for a commuter rail tunnel under downtown Washington. He was invited to present his proposals to Congressional committees on improving traffic in Washington, but the idea never gained significant traction.

Instead, D.C. Director of Highways Herbert Whitehurst argued that increases to road capacity would be sufficient to solve the District’s traffic issues. In 1942, though, Whitehurst did call on Congress to fund a study of possible streetcar grade separations for the District, like the one eventually built at Dupont Circle.

In 1944, the resulting study by J.E. Greiner Company produced the first detailed, professional proposal for a subway system for the District, consisting of three tunnels to carry streetcars to underground stations in downtown. By 1946, however, the original seven-mile proposal had been cut down to roughly half its original length to save money. By 1948, the project was essentially dead.

A call for modern rapid transit

While the District’s population started declining soon after World War II, the region’s population continued to rise, and suburban workers driving to downtown jobs continued to choke the road network.

To American planners in the 1950s, the natural solution to this sort of problem was a network of urban freeways. The 1956 Interstate Highway Act provided the funding for many American cities to build these freeways, eviscerating the walkable—and often predominately black—neighborhoods that separated downtowns from the new post-war suburbs.

In 1955, the Eisenhower Administration launched a study of the Washington region’s traffic problems, called the Mass Transportation Survey, with the goal of planning a system of highways and transit that would ensure sufficient capacity for projected numbers of commuters in 1980.

The resulting MTS proposal, released in 1959, was dominated by the extensive freeway network already planned by the District, Maryland, and Virginia highway departments. It also called for eight express bus lines running on freeways, but not in dedicated lanes, perhaps because the proposal was based on traffic modeling that assumed no freeway would ever become congested.

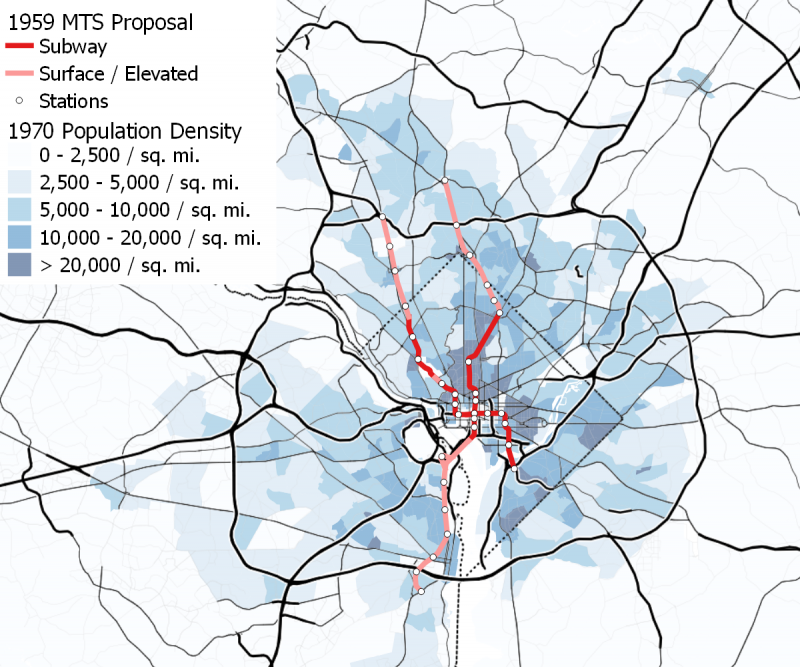

While the MTS proposal was dominated by highways, it did include two rail rapid transit lines, with about 33 route-miles. Interestingly, although this system was much smaller than today’s Metro network, the report introduced the idea of distance-based fares for subways in the D.C. region. It called for flat fares within four miles of the downtown transfer station, and distance surcharges for longer trips.

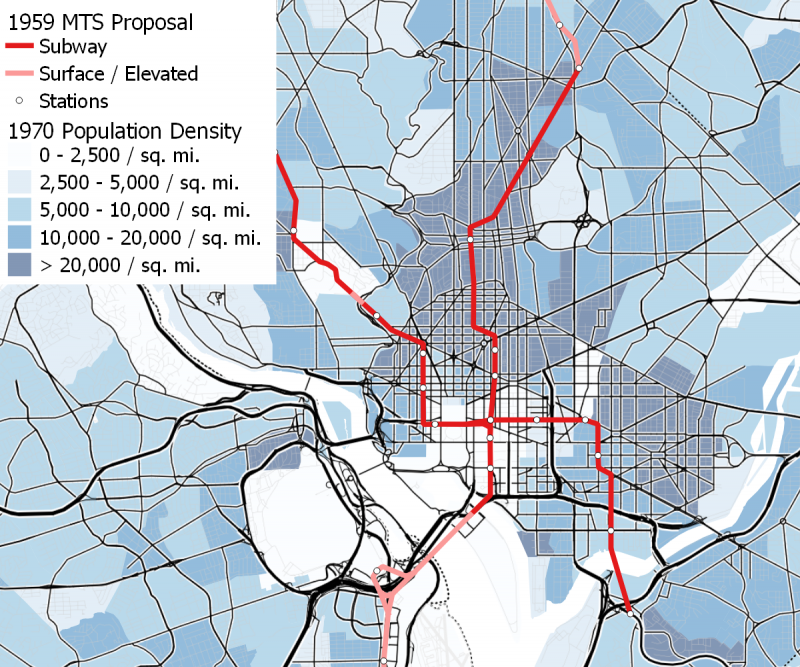

From Wheaton to near Fort Totten, the system’s longer line would have run in the median of the planned North Central Freeway, then south through the 14th Street and 7th Street corridors north of downtown. When it reached downtown, it would go underground and follow a route similar to Metro’s Yellow Line, then across a bridge over the Potomac to Arlington, where it would serve the Pentagon on an elevated loop, and finally south to Alexandria. Because the line was primarily intended to shuttle suburban passengers downtown—and because much of the city north of downtown was set to be demolished for freeways—the only station proposed between Logan Circle and Fort Totten was in Columbia Heights.

A shorter line was proposed starting at Pook’s Hill Road, near the I-270/Beltway/Rockville Pike interchange in Maryland. It would have run south in the median of the planned Northwest Freeway to Friendship Heights. From there, the line continued in a subway under Wisconsin and Massachusetts avenues, with stops at Tenleytown, the National Cathedral, Kalorama Heights, and Dupont Circle. Then, it would head south under 19th Street to Farragut Square and a station just west of the White House.

The line would then run east under E Street, to a transfer station to the longer line at 12th Street and additional stations at Judiciary Square and Union Station, before heading south to stations on the east lawn of the Capitol, near the Navy Yard, and in Anacostia.

The 1959 MTS proposal (below) is shown here superimposed over 1970 population density, the earliest available. The two northern branches to Montgomery County were to follow the then-proposed Northwest and North-Central freeways, while the southwestern branch largely followed existing railroad rights-of-way, but with some elevated portions. Maps of the 1959 MTS Proposal by the author.

The downtown portion of the 1959 MTS proposal is shown below, superimposed over 1970 population density, the earliest available. Image by the author.

Dreams of a monorail

Shortly after the Mass Transportation Survey was released in May 1959, an alluring midcentury idea emerged.

O. Roy Chalk, the owner of D.C. Transit—the company that operated the District’s bus and streetcar network—countered with his own proposal for a 116-mile monorail network. He claimed it could be built for roughly half the cost of the MTS transit proposal.

This was not the first time that Chalk had expressed interest in monorails: In 1956 and 1957, the Washington Post quoted him advocating for a monorail line to connect downtown D.C. to BWI, then known as Friendship International Airport.

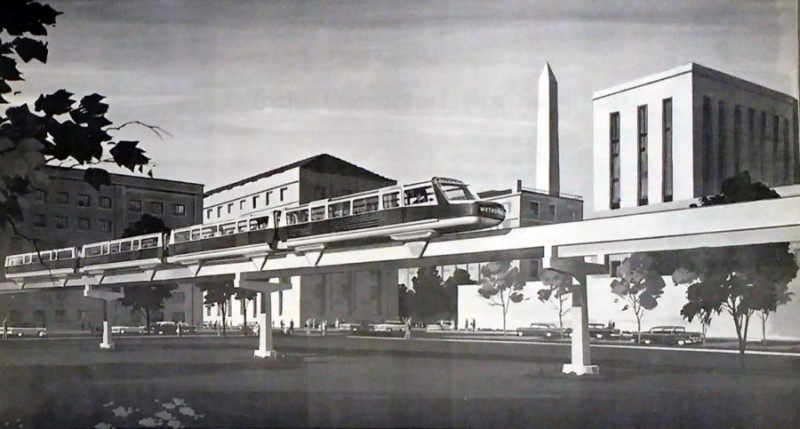

In his opposition to the MTS proposal, Chalk called rail rapid transit outdated “19th Century planning” and described monorails as “beautiful, silent-operating … suspended on graceful pylons for the most part.”

It seems likely that he was enraptured by the promise of futuristic new technology. Monorails loomed in the popular consciousness as the urban transportation of the future, leading to the construction of the Seattle Center Monorail in 1962.

That said, a major part of Chalk’s opposition to the MTS report seems to have involved the fact that it called for publicly built and operated transit, creating competition for his for-profit public transit company. While he called on Congress to provide funding for his monorail proposal, he made clear that he intended it to be privately built and operated by D.C. Transit, and he described the MTS proposal for publicly operated transit as “creeping socialism.”

The monorail proposal that Chalk promoted in 1959 was relatively light on technical data. As National Capital Planning Commission William Finley noted, it was largely based on a sales brochure from Lockheed, the manufacturer of the trains.

O. Roy Chalk’s 1959 proposal for a Lockheed-built monorail on elevated tracks along Maryland Avenue SE, by District of Columbia Public Library Washingtoniana Division; used with permission.

The proposal was built around the idea of building rapid transit “on the cheap,” with almost the entire system elevated on pylons that Chalk claimed—and Finley doubted—would only take up 30 inches of right-of-way in existing roadways. Finley also commented that the monorails, which were estimated to have a capacity of 24,000 passengers per hour, would have roughly half the estimated capacity of the rapid transit trains the MTS report called for.

Furthermore, the portion of the system south of Florida Avenue, where Congress banned overhead wires, called for 30-foot-wide open trenches rather than subways along Connecticut Avenue, 7th Street NW, and I Street NW. On 7th Street and I Street, those trenches would have taken up the majority of the width of the roadway.

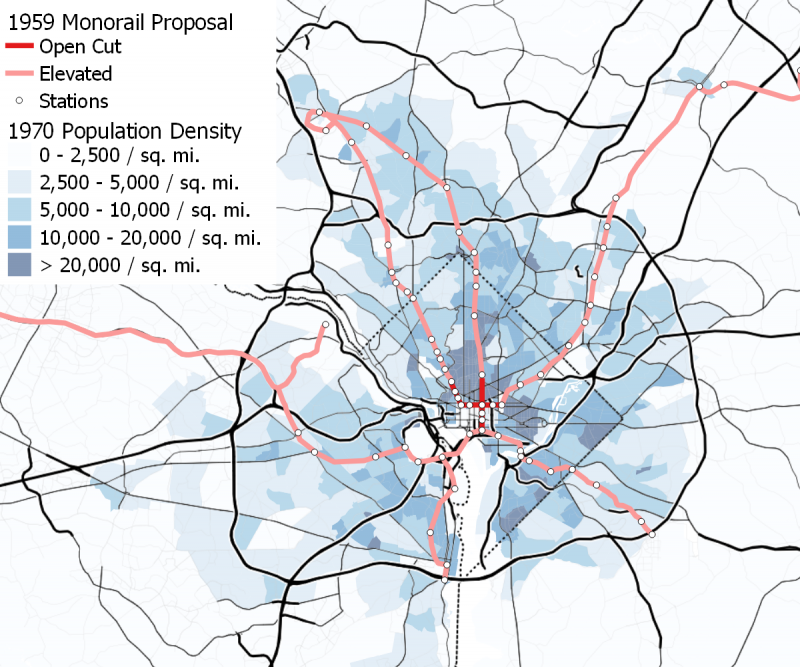

Despite the focus on cheap construction, the monorail proposal was ambitious in its geographic scope: each of the two lines was to be roughly 50 miles long. One line would run down Rockville Pike and Wisconsin Avenue, from downtown Rockville to Chevy Chase, then down the length of Connecticut Avenue in the District, across downtown on I Street, and northeast along railroad lines to Rhode Island Avenue. It would follow the streetcar right-of-way from Mount Rainier to Beltsville, where it would continue along US-1 and Maryland Route 198 to Fort Meade, and then to Friendship Airport.

The other line would also begin in Rockville, but would run along Viers Mill Road, Georgia Avenue, and 7th Street to the railroad tracks that run along Virginia Avenue and Maryland Avenue. From there, it would run southeast to Andrews Air Force Base and southwest to the Pentagon, with branches running to Alexandria, CIA Headquarters, and Chantilly (now Dulles) International Airport.

The federal and District governments seem not to have taken the monorail proposal particularly seriously, criticizing its dependence on untried technology and sketchy engineering details—at one point in late 1959, NCPC Director Finley issued a challenge to Chalk to actually build a monorail from Wheaton to downtown without government money if he was serious about his proposal. Meanwhile, the MTS report’s call for rail rapid transit alongside a massive freeway network was broadly accepted, and led to the creation of a federal agency intended to carry it out.

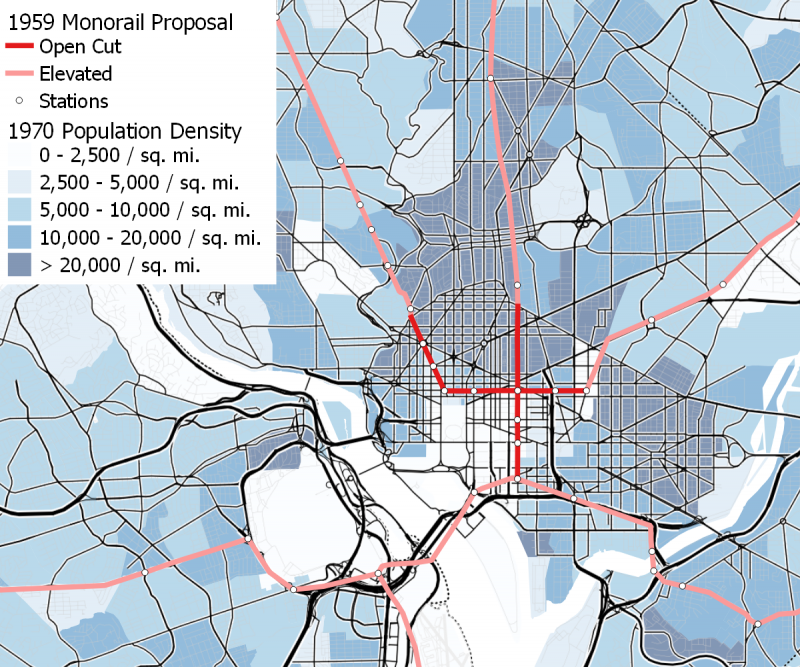

O. Roy Chalk’s 1959 monorail proposal is shown below, superimposed over 1970 population density, the earliest available. Station locations are estimates based on the list of “areas served” given in the proposal pamphlet. The branch that runs off the page to the west goes to Dulles Airport and the branch that runs off the page to the east goes to BWI airport. Image by the author.

The downtown portion of O. Roy Chalk’s 1959 monorail proposal is shown below, superimposed over 1970 population density, the earliest available. Station locations are estimates based on the list of “areas served” given in the proposal pamphlet. Image by the author.

1962 National Capital Transportation Agency proposal

In 1960, Congress created the National Capital Transportation Agency (NCTA) to refine the MTS proposals. Although it was initially essentially a continuation of the MTS organization, President Kennedy appointed more pro-transit leaders for the agency after his inauguration in 1961. In particular, Kennedy appointed a new director, Darwin Stolzenbach, who had been a freeway opponent as president of the Montgomery County Planning Association. As a result, the NCTA’s planning became more focused on transit as central to—rather than auxiliary to—the region’s transportation network.

In November 1962, the NCTA issued its own proposal for a rail transit network much more extensive than the MTS recommendation, with 89 miles of rapid transit and commuter rail service on what is now the MARC Penn Line between Union Station and Bowie. Like the MTS proposal, this plan involved two subway lines through downtown, but instead of a north-south line under 12th Street NW intersecting an east-west line under E St NW, the NTCA recommended an alignment that looks much more like what was eventually built: two east-west lines to serve the District’s largely east-west oriented central business district, one of which crosses the Mall on 12th St NW to serve the federal buildings in Southwest. The two lines even had a transfer station at the location of the present-day Metro Center station, along with one on the East Lawn of the Capitol.

Although the NCTA plan, like the earlier MTS plan, involved two subway trunks through downtown, its lines were divided into branches outside the central business district. The line, which ran through Southwest, was U-shaped and followed Wisconsin and Connecticut Avenues west of downtown and the B&O Metropolitan Branch railroad east of downtown, much like the present-day Red Line. However, the western side of the line included a branch along Columbia Road to Columbia Heights, much like today’s 42 bus and the streetcar that preceded it; the eastern side of the line included a branch, similar to the Green Line but about a mile to the east, running in the median of the then-planned I-95 inside the Beltway to Cherry Hill Road.

The other downtown trunk—which had stops at Metro Center, Gallery Place, and Judiciary Square—crossed the Potomac and divided into two branches, roughly mirroring the present-day Orange and Blue lines. However, the Orange Line equivalent began running in the I-66 median immediately after a subway stop in Rosslyn—today’s Rosslyn-Ballston corridor was the product of a later push by Arlington County—and ran further west to better serve the City of Fairfax, while the Blue Line equivalent did not serve National Airport. On the eastern end, the line served Pennsylvania SE for a short distance before turning south to serve the Navy Yard and historic Anacostia, and then continuing south through a largely undeveloped corridor in Prince George’s County to Rosecroft Raceway.

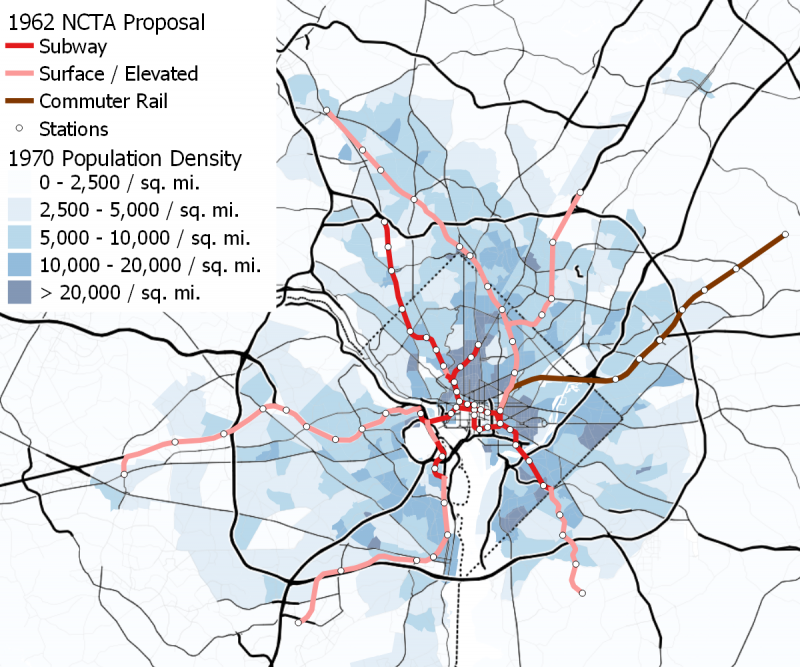

The 1962 NCTA proposal is shown below, superimposed over 1970 population density, the earliest available. The line to Fairfax was to be built in the median of I-66, and the line to College Park was to be built in the median of I-95, while the line to Rockville was to follow the Metropolitan Branch Railroad right-of-way, some of which would also have a freeway built along it; the Alexandria line would be built along the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad. The construction techniques for the Suitland and Bethesda lines were not clearly indicated in the report, but it appears that elevated tracks were contemplated for the former and a subway for the later. Image by the author.

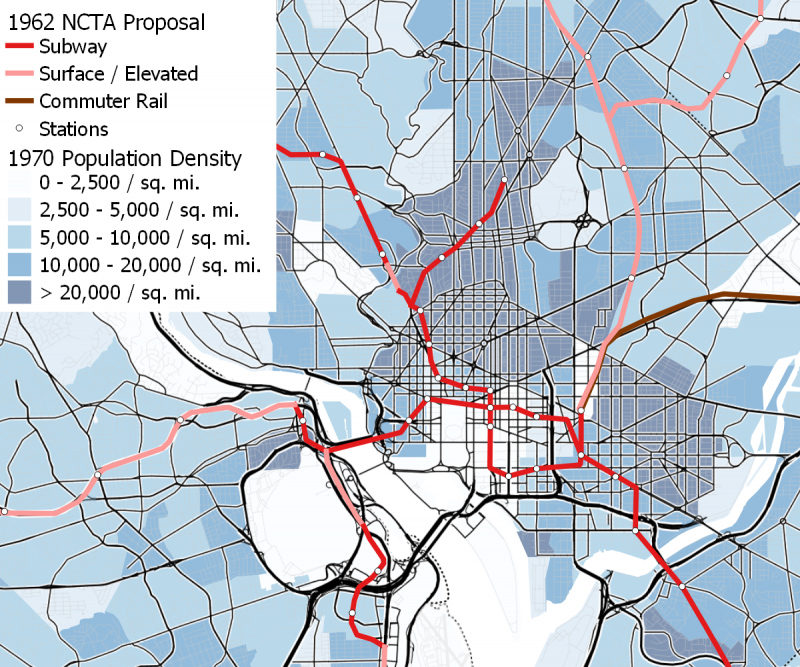

The downtown portion of the 1962 NCTA proposal is shown below, superimposed over 1970 population density, the earliest available. Image by the author.

Chalk and D.C. Transit continued to propose monorails in 1962 and 1963

Chalk’s 1959 proposal failed to gain traction, but he continued to propose monorails into the early 1960s. In 1962, he released a proposal for a line to Dulles Airport using a hybrid type of monorail called “superail” by its inventor, which was supposedly capable of running on standard-gauge rails as well as monorail beams.

The superail line to Dulles Airport would have made use of the right-of-way of the Glen Echo trolley from the Georgetown Car Barn to Glen Echo. This right-of-way had become available because the trolley had been abandoned in early 1960 due to a Congressional requirement that D.C. Transit eliminate all of its streetcars by 1963. From Glen Echo, it would have crossed the Potomac to serve CIA Headquarters, and then run along Virginia Route 123 and the Dulles Toll Road to Dulles.

In several respects, this plan was significantly less practical than Chalk’s 1959 monorail proposal, and the November 1962 report in which the NCTA introduced their initial recommendation for an 88-mile system includes an appendix outlining three reasons why the NCTA did not feel the proposal—which they noted “like most other so-called monorail systems…uses two rails, placed close together”—merited serious consideration.

This appendix pointed out that the route into D.C. ran through the lowest-density corridor possible, meaning that the entire route would need to depend almost entirely on airport traffic; it observed that it would make more sense to serve the airport with an extension of the rapid transit system proposed by the NCTA, which would run through more densely-populated areas and actually connect to downtown, rather than requiring passengers take a bus or cab from the Georgetown Car Barn to downtown; and calculated if superail vehicles were to run in the NCTA’s proposed subways, their complicated dual-running gear would require the tunnels be a foot and a half higher than otherwise required, increasing construction costs by $24 million ($200 million today).

Superail was not Chalk and D.C. Transit’s final monorail proposal, either. In the spring and summer of 1963, D.C. Transit proposed two purely suburban monorail lines that would collect passengers in the suburbs and take them to transfer points to express buses to downtown.

The first proposal, in March 1963, was for a monorail on Viers Mill Road from Wheaton to Randolph Road, with potential extensions to Rockville and along Georgia Avenue to Silver Spring. Although Montgomery County officials seem to have initially been supportive, the plan was killed by the Maryland’s State Highway Administration and attorney general, who decided that D.C. Transit could not place monorail supports in the median of a state highway.

In July 1963, D.C. Transit followed up with an alternate proposal to get around this decision: a monorail from Mount Rainier to Branchville (near Greenbelt Road in College Park) along the recently-abandoned 82 trolley right-of-way, some of which is now the roadbed of Rhode Island Avenue and some of which is now the Hyattsville, Riverdale, and College Park Trolley Trails. The line would then have headed west to serve the then-under-construction Beltway Plaza Mall, though it is not clear how it would have gotten there without running on Greenbelt Road, which was also a state road.

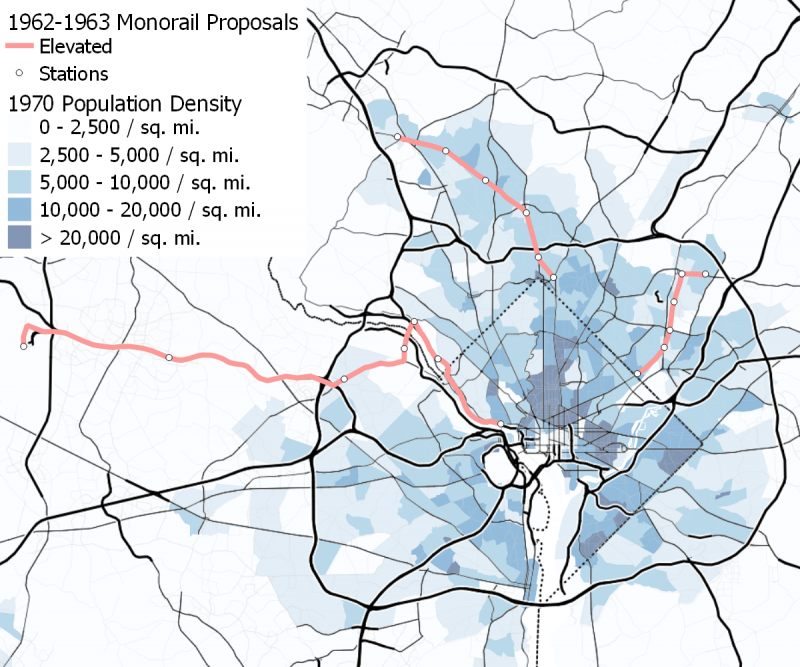

O. Roy Chalk’s three monorail proposals from 1962 (“superail” to Dulles Airport) and 1963 (Rockville-Silver Spring and Greenbelt-Mount Rainier) are shown below, superimposed over 1970 population density. Station locations for Superail are taken from the map included in the proposal; station locations on the Maryland routes are based on stations proposed in the 1959 monorail plan. Image by the author.

The 1965 National Capital Transportation Agency “bobtail” plan

Although the 1962 NCTA transit plan was less ambitious than what was eventually built, Stolzenbach’s desire to cancel freeways and build more transit was unpopular with other leaders. His tendency to make enemies of his opponents didn’t help matters.

In 1963, in an attempt to save the plan, the NCTA pushed Congress to authorize a truncated “bobtail” version of the network. This plan had no I-95 line, truncated the Silver Spring-Rockville line at Silver Spring, had only three Virginia stations (in Rosslyn, at the Pentagon, and in Pentagon City), and truncated the other branches at Anacostia, Van Ness, and 19th Street and Columbia Road.

The two downtown trunks were consolidated into one north of the Mall, but the commuter rail line to Bowie remained intact. Despite these changes, the House of Representatives rejected a bill to fund the initial bobtail plan that December.

The NCTA plan was not dead, however. In 1965, the new Congress passed a modified version of the “bobtail” plan, with the full Columbia Heights branch—which served some of the densest parts of the District—restored, the Rosslyn and Pentagon branches consolidated into a single line, and the Anacostia branch rerouted along a route similar (but not identical) to the current Orange Line to a station at Minnesota Avenue.

The commuter rail line to Bowie was also dropped from this portion of the plan. In addition, to allay concerns from labor unions that a government-run transit agency would weaken employees’ collective bargaining rights, the 1965 bill called for a private company to operate the rail system.

The NCTA proposals ended up having a significant role in shaping what was eventually built: the eastern branch of the Red Line from Silver Spring to Union Station, the idea of two east-west downtown trunks, and the route of the Red Line on Connecticut and Wisconsin Avenues from the Beltway to Farragut Square all first originated in NCTA proposals.

Although resistance from Congress and the highway lobby forced it to be cut down significantly, the original 1962 NCTA proposal was also quite similar to Metro as it was originally built: getting regional-buy-in on the plan approved by Congress in 1965 turned out to require putting back in much of what was cut out.

Likewise, D.C. Transit’s and labor unions’ push for a privately-operated system went nowhere in the end, even though the 1965 bill required one. Even bus service—which the MTS and NCTA had never called for a government take-over of—ended up being publicly operated as D.C. Transit became so unprofitable in the late 1960s that O. Roy Chalk himself pushed for the government buy-out.

When WMATA finally took over D.C. Transit’s operations in early 1973, the region’s suburban bus companies quickly asked to be bought out as well, leading to the creation of a region-wide bus system to be operated alongside Metro.

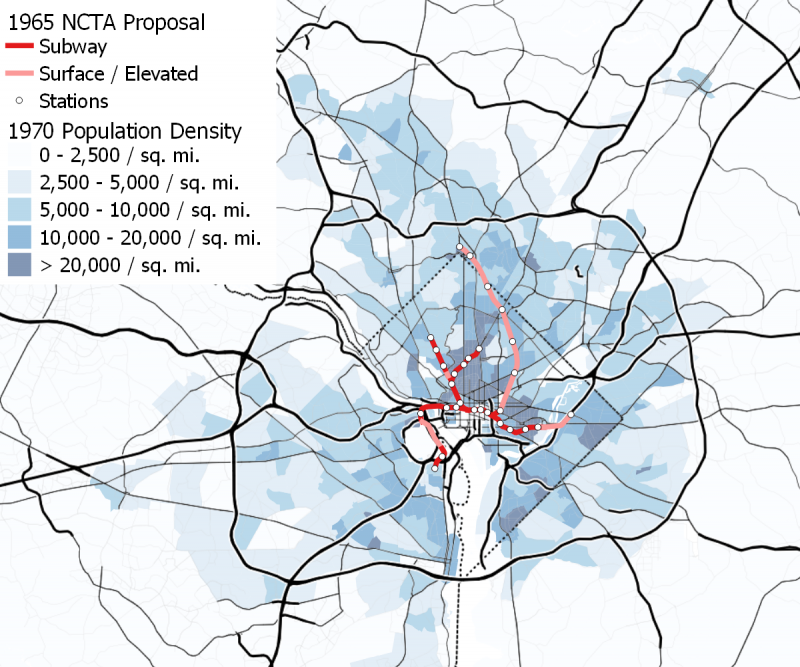

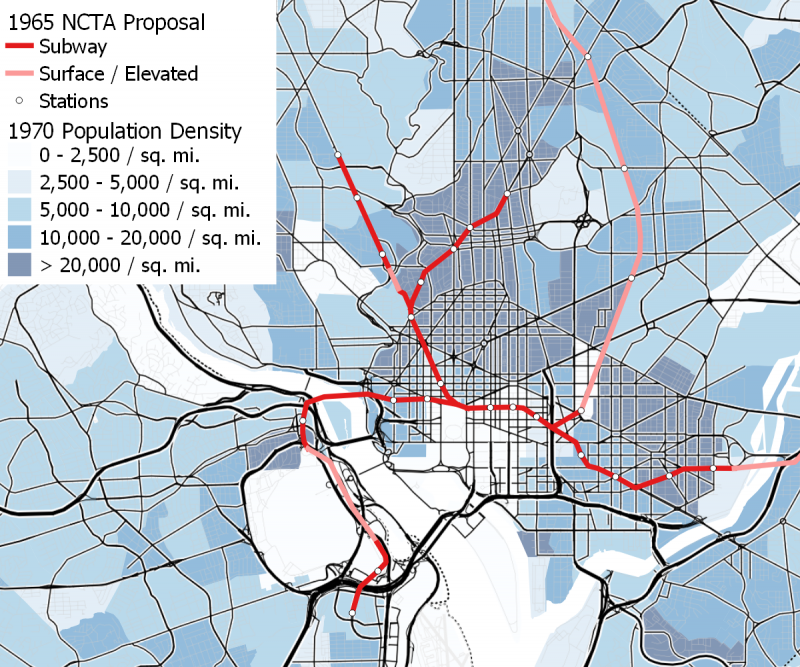

The modified NCTA “bobtail” plan, which was approved by Congress in 1965, is shown below, superimposed over 1970 population density. Image by the author.

The downtown portion of the modified NCTA “bobtail” plan, which was approved by Congress in 1965, is shown below, superimposed over 1970 population density. Image by the author.

Sources

MTS and NCTA Proposals

The book The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro by Zachary M. Schrag is my main source on the history of the Mass Transportation Survey and the National Capital Transportation Agency.

Details on the MTS rapid transit proposals are taken from—and my map is based on—the “Mass Transportation Survey, National Capital Region: Civil Engineering Report,” issued in January 1959, a PDF of which is available on the website of the Eno Center for Transportation.

Details of the 1962 NCTA proposal are taken from—and my map is based on—the NCTA’s November 1962 report “Transportation in the National Capital Region: Finance and Organization,” which can be found online on the Hathitrust website. Stephanie Diederich provided assistance in overlaying the map of the system shown in the report on a present-day road map to allow the identification of station locations. O. Roy Chalk’s continued opposition to the project and advocacy for monorails was discussed in the Washington Post Times Herald, “NCTA Transit Plan Assailed at Hill Hearing, by Jack Eisen, 26 July 1963, page B1.

Details on the 1965 NCTA “bobtail plan” are taken from—and my map is based on—the NCTA’s 1965 report “Rapid Rail Transit for the Nation’s Capital, a PDF of which is available on the website of the Eno Center for Transportation.

O. Roy Chalk’s Monorail Proposals

The only modern source I have found discussing Chalk’s monorail proposals is a WAMU article by Martin Austermuhle, “The Washington Region Has Metro. But It Could Have Had a Monorail. (Seriously.),” 13 March 2017.

My source on Chalk’s early interest in monorails are two articles from the Washington Post and Times-Herald: “Chalk sees Helicopter Service to Friendship” by Carroll Kilpatrick, 13 December 1956, page A1 and “Transit System in the Air No Bubble” by Robert C. Albrook, 28 July 1957, page E2.

Chalk’s release of his monorail proposal at a Senate subcommittee meeting about D.C. Transit’s sightseeing and transit operations was reported on in the Washington Post and Times-Herald, “Chalk Proposes Area Monorail for Fast Transit” by Jack Eisen, 9 June 1959, page B1. A more detailed description of his proposal can be found in the booklet D.C. Transit produced to publicize it: “A Monorail System for Washington, D.C. Area,” a copy of which was read into the records of the hearing before the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia Subcommittee on Public Health, Education, Welfare, and Safety of the first session of the 86th Congress on bill S. 304 “To Insure Effective Regulation of D.C. Transit System, Inc., and Fair and Equal Competition Between D.C. Transit System, Inc. and Its Competitors” starting on page 201.

NCPC Director Finley’s objections to Chalk’s monorail proposal are detailed in Washington Post Times-Herald, “Finley Dares Chalk to Build Monorail Route as Sample,” by Morton Mintz, 15 November 1959, page B1.

My main source on Chalk’s 1962 “superail” proposal is the report “Proposal for a Demonstration Model of a Controlled High-Speed Superail Transit System for Mass Transportation, Washington, D.C. to Dulles International Airport,” released in January 1962 and co-authored by D.C. Transit System, Inc. and Colonel S. H. Bingham, (Ret.), the inventor of the superail system. While I was unable to find an original copy of the report, a selection of pertinent pages is included as an appendix to Richard David Rush’s Bachelor of Architecture thesis from MIT, dated 23 January 1967.

Bryan Kneedler and the Anacostia Trails Heritage Area’s Twitter account, @mdmilestones first brought Chalk’s 1963 plans for surburban monorails in Maryland to my attention and inspired the research that became this project. The only references to Chalk’s 1963 plans that I have been able to find are several newspaper articles. The Viers Mill Road monorail was introduced at length in the Washington Post Times-Herald, “D.C. Transit Plans Monorail in County” on 24 March 1963. The Mount Rainier-Branchville monorail line was introduced and the reasons for the abandonment of the Viers Mill Road project were mentioned in the Washington Post Times-Herald, “Monorail Considered by D.C. Transit to Link Mt. Rainier and Branchville” on 26 August 1963, page B1 and in the Prince George’s Post, “Test Monorail System is Proposed for Old Streetcar Right of Way” on 29 August 1963, page 9.

Backgrounds for Maps

The 1970 population data shown in the background of my maps is from the 1970 Decennial Census, accessed through the IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System (NHGIS) project at the University of Minnesota. Although the US Census Bureau’s online data portal only provides relatively recent data, NHGIS has digitized a large amount of older data from decennial censuses going back at least to the start of the 20th century. However, the data at the census tract level that I used for these maps is only available starting with the 1970 Census. I previously discussed this data in an article on changes in the D.C. area’s population density since 1970.

The present-day road network shown in the maps uses Stamen Toner Lines map tiles, produced by Stamen Design.

This article also appeared at Greater Greater Washington.