On May 25, 2021, D.C. Policy Center’s Executive Director Yesim Sayin testified before the Committee on Business and Economic Development to discuss how the District could examine its tax regime through a lens of racial equity, the information gaps we need to fill, and a potential means of such a review. You can read her testimony below or download a PDF version here.

Good morning, Councilmember McDuffie, and the members of the Committee on Business and Economic Development My name is Yesim Sayin Taylor, and I am the Executive Director of the D.C. Policy Center—an independent non-partisan think tank advancing policies for a strong and vibrant economy in the District of Columbia. I thank you for the opportunity to testify on tax proposals that can help support equitable wealth building in the District of Columbia.

In my testimony, I will first focus on two tax proposals that have been presented to this Committee as a means of achieving racial equity in wealth building. I will then turn to the broader issue of examining the District’s tax regime through a lens of racial equity, including the information gaps we need to fill and a potential way forward.

An income tax increase on high-income households would not address the underlying reasons why tax policies could amplify racial inequities.

As in past years, once again, there are calls on the District’s leaders to increase income taxes on higher-income households during this budget cycle.[1] But unlike past years, racial justice, and not just the need to raise revenue, is a central argument offered in favor of higher individual income taxes.[2] After the tragic deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and too many others to name, the focus on racial equity is vitally important and necessary. And the urge to address racism through a revamped tax code, understandable. However, proposals to increase District’s income taxes in pursuit of racial equity do not address the underlying reasons why tax policies could amplify racial inequities.

Racial inequities in the tax code are not primarily a function of the District’s own tax laws, but are largely tied to the federal tax code, especially to various preferential tax treatments of wealth.[3] For example, mortgage interest deduction—a very popular tax preference—is a transfer from all taxpayers to those who are fortunate to be able to afford a home. Preferential treatment of retirement savings, pensions, and college savings benefit those who can save for retirement or their children’s college, amplifying wealth disparities. Because the District’s definition of taxable income conforms to the federal definition (with a few exceptions), many of the federal laws that reduce federal income calculations for tax purposes also reduce District residents’ taxable incomes.[4]

In contrast, the District’s tax laws—especially its income tax—is far more progressive, and far more targeted to benefit lower-income households, this having many of the elements[5] that can reduce racial disparities. According to ITEP, whose research[6] is offered by advocates to justify income tax increases, the District has one of the most progressive income tax regimes[7] in the country. In addition to progressive income tax rates, the District has a strong Earned Income Tax Credit,[8] a targeted childcare credit, a circuit-breaker program targeting low-income homeowners and renters, all of which provide additional protections for lower-income District residents. Further, unlike the federal government, the District taxes long-term capital gains as ordinary income,[9] and not at a preferential rate. As a result, among the jurisdictions that make up the Washington metropolitan area, the District has the lowest tax burden (income, sales, real property, car taxes combined) for households that earn up to $150,000 annually,[10] and the second highest effective income tax rate on households earning $150,000 or more when compared with the largest city of each of the fifty states.[11]

Even with this information, the District’s options for improving racial equity through an income tax adjustment is unfortunately limited. The obvious alternative to a tax increase is to decouple from the federal law to eliminate such preferential treatments but doing this is politically difficult;[12] makes tax administration harder;[13] and without a change in the federal code, would also significantly reduce the attractiveness of the city and weaken its competitive position in the region, and therefore could end up hurting revenue (and consequently spending). Both Maryland and Virginia conform to the federal definition of income.[14] Thus, for example, if the District decouples from federal law, fewer households will likely relocate in the District if they cannot deduct their mortgage interest from their taxes, and more wealth will be invested elsewhere in the region (in homes, retirement accounts, or college accounts) if tax treatment of this wealth is more favorable.

Increasing property taxes on high-value properties to address wealth disparities needs careful design.

The District’s residential property tax rates and tax burdens are lowest in the region.[15] So one proposal receiving attention is to increase property taxes on high-value properties. This is, in fact, the closest the District can get to a wealth tax. Such a tax might cause the least distortions since it would be imposed on an asset (the property), which cannot be moved. Further, it would allow the District to recoup some of the returns on public investments as property values are highly contingent on their proximity to things like good schools, transportation, amenities—all functions of government services.

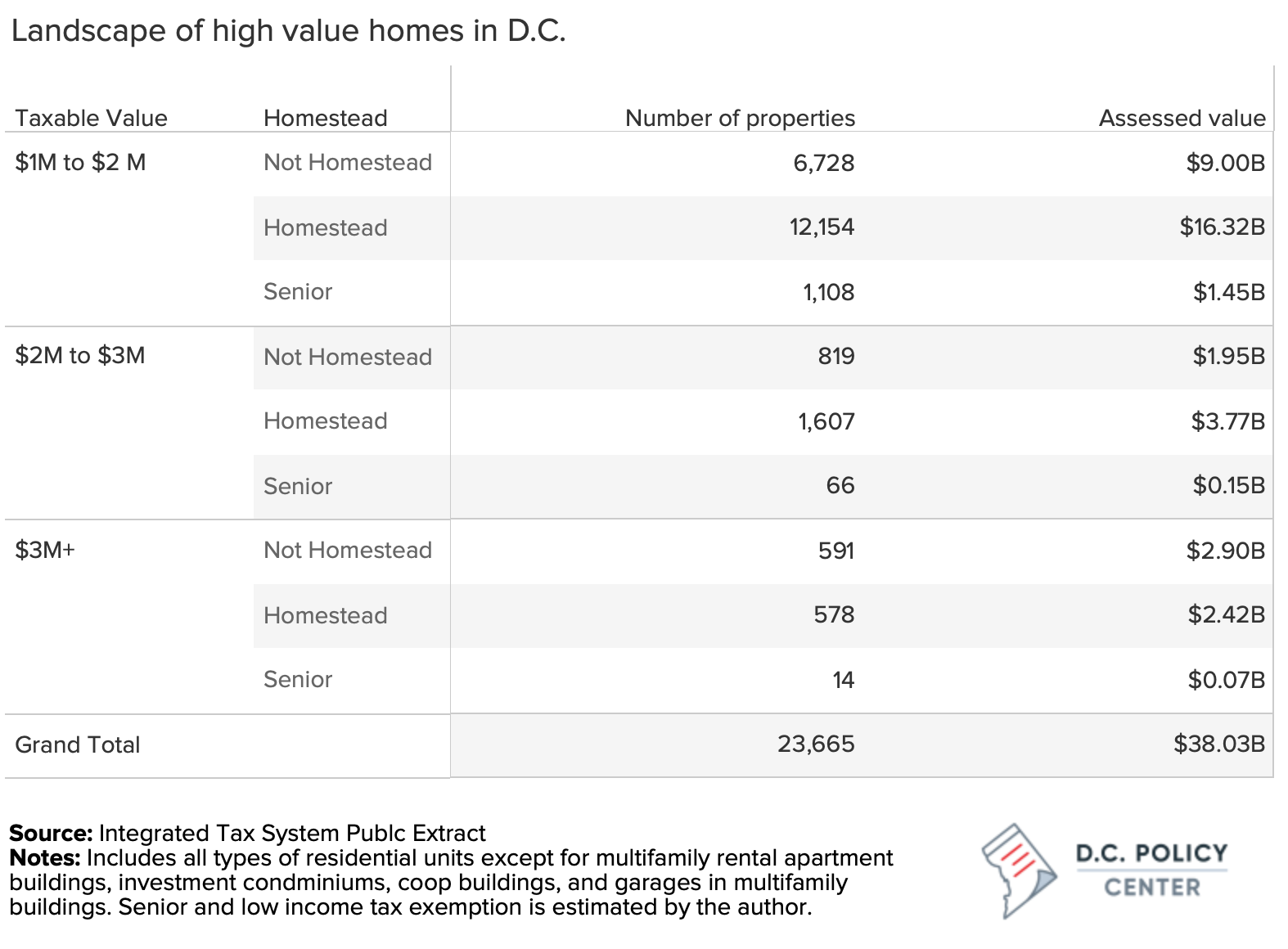

An analysis of the District’s real property tax database shows that there are over 23,665 properties[16] assessed at $1 million or more collectively valued at $38 billion. Increasing the property taxes on these properties, for example, by 1 cent would generate $3,8 million per year. If the high-value threshold were set at $2 million, the base would include 3,600 homes collectively assessed at $12 billion.

In the context of a high-value property tax, the policy design should consider the following elements:

- Bracket creep: What value qualifies a home as a “high-value” and how should this change over time or be indexed to inflation?

- Cooperative buildings: Should coops be included in the tax base, and if yes, how is the per-unit value calculated?

- Parking: How should units in multifamily buildings with a parking space be treated?

- Other exemptions: Should properties that qualify for a low-income senior tax rates be excluded?

- Income: Should there be a separate circuit-breaker program for high-value homes?

Additionally, the city could examine other tax exemptions that could be removed with similar affects.

A holistic review of all tax policies is needed.

An even better approach to tax policy would be to apply a racial equity lens to all the District’s taxes that (a) considers past and current systemic racial inequities; (b) identifies who benefits or is burdened from a decision, and (c) analyzes data to better understand impacts and outcomes by race.

To successfully incorporate a racial equity lens to tax policy, the District must have the data. At present, the District does not collect race and ethnicity data from taxpayers, and tax proposals considered at the Council rarely include a racial impact analysis.[17],[18] While convincing taxpayers to share information on their race and ethnicity may require significant public education and assurances that the tax agencies won’t abuse this information,[19] the city can obtain at least some of this information by using what it already collects:

For example, the District’s Department of Employment Services routinely collects race and ethnicity data from employers for each employee eligible for unemployment benefits, and this information can be matched to income tax data, covering all District residents who have, at some point in the last 30 years, worked in a salaried job in the city. By merging information from employer filings with tax return data, the District can begin unpacking the racial equity implications of both federal taxes and the city’s own income tax code. Creating this information for real property and sales taxes is more difficult but with some effort, we can know more about racial disparities in burdens associated with these taxes. For real property taxes, for example, the District could consider matching mortgage finance data to real property tax rolls, or match home addresses to individual income tax filings. For sales taxes, it could use credit card data or consider instituting a periodic household expenditure survey.

At the same time, we need to remember that good tax policy raises as much revenue as possible for public services with the least amount of distortions in economic decision-making and disruptions to economic activity. And this means the District must remain competitive in the region, offering a high quality of life for a relatively low price for its current and future residents, workers, and businesses.

The city will be well-served to think through its tax system through a Tax Revision Commission—an institution that has served the city well in the past. The D.C. Council recently passed legislation to establish a new Tax Revision Commission and charged it with considering the racial equity impacts of the District’s current tax code in addition to efficiency and competitiveness factors.[20] This is timely, not just because of the importance of using a racial equity lens, but the growing pressures to increase the District’s competitiveness given the weaknesses in population growth, job losses, increased commercial vacancy rates, and the impact of COVID-19 on the desirability of urban areas, with a resulting spread of work from urban employment centers to smaller cities and suburbs.

The city should consider other policy changes that can reduce the racial wealth gap with greater certainty and longer-term impacts.

A review of fines and fees[21] that disproportionately target communities of color and underserved communities, elimination of restrictive land use policies[22] that make it difficult to build housing and increase displacement, removal of unnecessary professional licensing requirements[23] that close the doors to opportunity, and elimination of barriers to starting new businesses by simplifying business applications[24] and increasing the threshold[25] for Clean Hands background checks are some of the steps the city should take to help the city’s Black and brown communities begin building wealth. All of these are much harder to do than increasing income taxes on the rich, but they are necessary to open doors of opportunity for the District’s most underserved and disadvantaged residents.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify on this important matter. I am looking happy to answer any questions you might have.