On May 21, 2021, D.C. Policy Center’s Executive Director Yesim Sayin testified before the Special Committee on COVID-19 Pandemic Recovery to share ideas on how the District can gradually transition out of the public emergency and wind down safety net supports in the least disruptive ways. You can read her testimony below or download a PDF version here.

Good morning, Councilmember Allen, Councilmember Gray, and the members of the Special Committee on COVID-19 Pandemic Recovery. My name is Yesim Sayin Taylor, and I am the Executive Director of the D.C. Policy Center—an independent non-partisan think tank advancing policies for a strong and vibrant economy in the District of Columbia. I thank you for the opportunity to testify on how the District could transition out of the public emergency by using its current resources to create a more equitable and prosperous future.

In the last fourteen months, the D.C. Council has taken important actions to minimize the destabilizing impacts of the pandemic-induced economic downturn on District residents. These measures—such as the eviction moratorium—offered protections for households experiencing financial hardship.

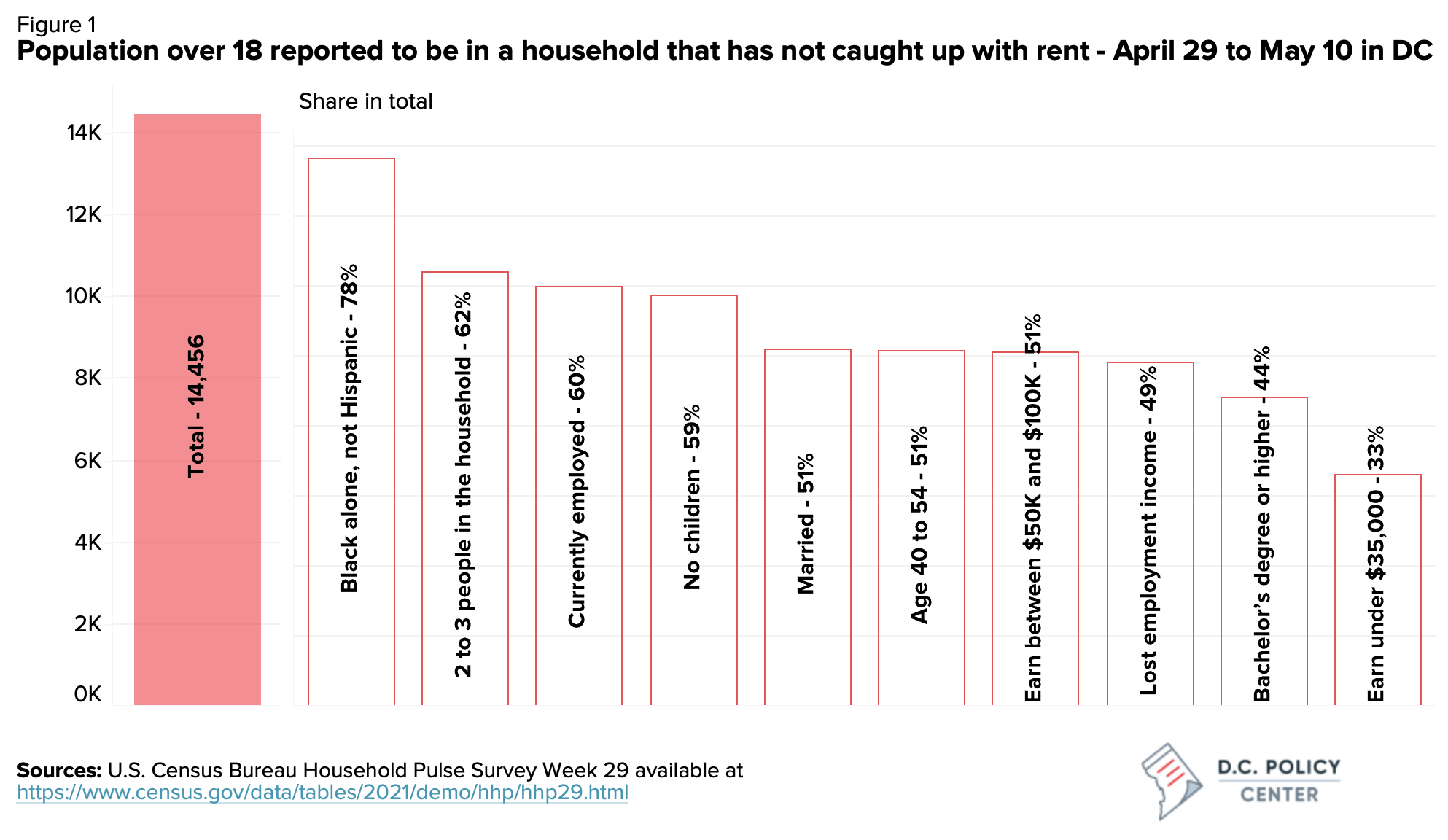

A difficult byproduct of these measures is that they create a future liability: many residents currently face a daunting prospect of paying back months of missed rent without extra financial resources. What is different now, from the beginning of the pandemic when these measures were first employed, is the District’s access to significant federal resources[1] that can be deployed to aid renter households in distress and pay for much of this liability. Unfortunately, some of this federal money has a timestamp on it: the current round of Emergency Rental Assistance funds must be spent by September of 2021,[2] and the District could lose both the unspent amounts and future federal rental assistance if the city cannot get the assistance to renters.[3]

In my testimony I will offer two potential policies that can help support an equitable recovery and maximize the use of federal dollars. The D.C. Policy Center is researching more ideas on investments that could further contribute to an equitable recovery. We will share our findings with this Committee when this work is complete. I have also included a third recommendation on the gradual relaxation of pandemic related restrictions, which can help support a healthier housing market as the economic recovery begins.

1. Provide tenant’s cash incentives to participate in rental assistance applications

The District of Columbia—like many other municipal and state governments—is having a hard time moving the federal funds quickly to aid renter households.[4] Tenant participation, which is necessary for final approval of rental assistance, has reportedly been slow. This could, of course, change with more time and more outreach.

Just this week, the D.C. Council considered ending the eviction moratorium as a means of creating greater urgency for the tenants to participate in the application process. After much debate, the Council put off deciding the fate of the moratorium, partly to better understand why tenant participating might be low, and partly to look for the least disruptive way of ending the moratorium. Unfortunately, the city does not have much time to find answers: the federal deadline makes the cost of waiting too high.

The goal of the federally funded rental assistance program should be to get assistance to qualified tenants as quickly as possible before the federal deadline. To this end, the city should consider incentives: research shows that cash incentives increase participation in various government—specifically human services—programs.[5] Based on this research, paying tenants to apply for rental assistance would not only help increase public awareness and participation, but it would also get cash in the hands of lower-income households.

We estimate that such a program would have modest costs, especially when compared to the federal funds at risk. At an average monthly rent of $2,250, for example, the $200 million committed from the federal government is sufficient to pay for 91 thousand months of rent. This would cover six-month’s worth of rent for 15,000 renter households. If the District offered cash incentives of $500 to each applicant, these incentives would cost the city $7.5 million, or four percent of the total federal funding.

The incentives could be paid from the unrestricted federal fiscal aid and can be administered through the Office of Tax and Revenue in the form of stimulus checks. By design (given the eligibility requirements of the federal funding), such incentives would be targeted to low-income households and communities of color, contributing to an equitable recovery. `

2. Build up the Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund

The pandemic took a big toll on the District’s unemployment system. In January of 2020, the District’s Unemployment Trust Fund balance was $525 million; at the end of 2020, it was down to $63 million.[6] While claims have declined significantly from their peak from a year ago, the number of weekly initial claims (1,583 as of May 1) and total claims (39,400 as of April 24) are still much higher compared to their levels prior to the pandemic (about 500 weekly initial claims and 7,100 continuous claims). The District has already moved to the highest possible tax rate in its current unemployment tax schedule, but the monthly benefits paid (about $21 million) still exceed monthly tax collections (about $15 million).

Building up the District’s Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund could take many years. Even during the years with the strongest labor market outcomes, the District added about $41 million each year to its Trust Fund Balance.[7] Even if the labor market were to improve to match these conditions, it would take over ten years to get to pre-pandemic levels of fund balance.

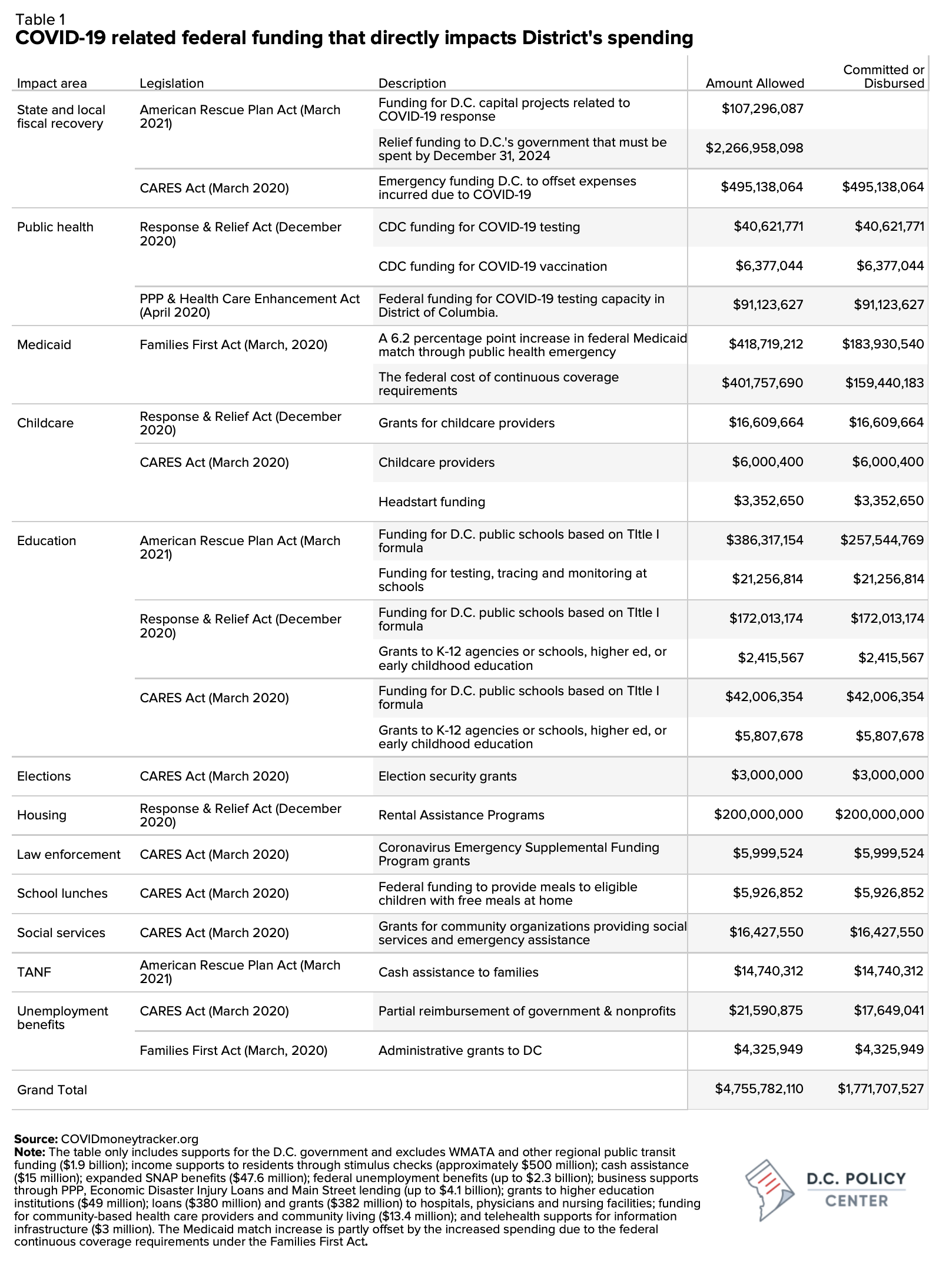

The District should consider allocating some of the federal fiscal aid (see the sources of funding from the federal government in Table 1 below) to build up its Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund. This is an appropriate use of the federal fiscal aid because it would help quickly solve a fiscal problem directly linked to the pandemic, matching a one-time resource to a one-time need.

This policy would also have the benefit of delaying or preventing tax increases on businesses at a time when the economy is ailing, especially benefiting the businesses that have been hurt the most throughout the pandemic. While the investment will be one time, the impacts would have long-term effects on the cost of hiring in the District of Columbia. Research shows that small businesses owned by Black residents have experienced greater negative impacts from the pandemic than businesses owned by white residents.[8] Increasing taxes in future would only create additional barriers to Black entrepreneurship.

3. Supporting a healthier housing market by removing rent freezes on vacant units

Current rules related to the public health emergency includes a provision that prevents housing providers from increasing rents, including rents on vacant units. In rent-controlled buildings, providers are ordinarily allowed to raise rents by 10 percent (20 percent if the previous tenant had occupied the unit for longer than ten years). This higher rent increase allowance permits providers to bring rents closer to market rate (especially if the unit previously had a tenant with a long tenancy), while staying true to the price stabilization goal of rent control.

Housing providers are reporting that they are responding to the rent freeze on vacant units by not putting their vacant units up for rent.[9] This is because under current rules, providers would have to offer their vacant unit at the same rental rate paid by the previous tenant. This may not be a big problem if the previous tenant was in the unit for a year or two, but if that tenant had occupied the unit for a very long period, then the rents allowable under the rent freeze provision could be too low to make it worthwhile to lease and operate.

The impact of income loss on housing providers—especially smaller providers–can be substantial. For example, a loss of $150 in monthly rental income due to the vacancy freeze may seem modest, but its impact on the housing provider’s asset value is $36,000 (at a capitalization rate of 5 percent). By holding back the unit for three months, providers might forgo some rental income, but would not take the significant hit to their asset values.

The equity impact of the rent freeze on vacant units is at best, debatable. And when units are taken out of the market, the outcome is nor supportive of low-income renters. Fewer units mean higher rents, and fewer units in rent-controlled buildings take away supply of the District’s affordable housing stock.[10] The Council should seek more information on this, and consider eliminating the rent freeze provision on vacant units.

I thank you for the opportunity to testify. I am happy to answer any questions you might have.