This report analyzes the District’s Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) using data from multiple sources, including housing and tax records, multifamily sales data, and reports on subsidized housing. It evaluates sales and data on tenant association formations from 2012 and 2023 to measure TOPA’s effectiveness. Additionally, qualitative insights from thirteen interviews with key stakeholders provide a broader perspective on TOPA’s impact. Access a pdf version of the full report here and the one-page summary here.

Executive summary

The District’s Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) was enacted over 40 years ago, during a time of minimal rental housing construction and widespread condominium conversions, prompting concerns about tenant displacement. TOPA gave tenants an opportunity to purchase the units they lived in and stay in place.

Initially, TOPA provided tenants a “right of first refusal” to collectively purchase their units. Over time, its scope expanded: a 1995 amendment allowed tenants to transfer purchase rights to housing providers, permitting units to remain as rentals. Although tenant purchases remain possible under the law, they are rare because lenders have little interest in funding tenant purchases and the logistics of acquiring, owning, and maintaining an apartment building are very complex.

In 2005, TOPA was amended to broaden the definition of “sale” to include recapitalizations or internal ownership changes, making many more transactions subject to TOPA even when there is no change in building management. And in 2018, single-family homes were exempted to streamline sales. Meanwhile, the District’s rental housing picture also changed considerably. Rental housing construction surged after 2007, adding 42,980 units—31 percent of the city’s total rental stock—primarily in large buildings within newly developed neighborhoods like NoMa, The Wharf, Capitol Riverfront, and Union Market.

Today, TOPA laws lack a clear objective. While the original intent was to prevent displacement and preserve affordable housing, TOPA is now used to negotiate for repairs, new amenities, rent concessions, or cash awards for existing tenants. The most important task for our elected officials is to define clear goals for TOPA, legislate accordingly, and collect comprehensive data on TOPA outcomes to ascertain the conditions under which TOPA laws can successfully serve their purpose.

Where is TOPA most viable?

To evaluate the effectiveness of TOPA laws, it is essential to understand the composition of D.C.’s rental market. The District’s stock in rental apartment buildings is essentially made of two parts: older, smaller, rent-controlled buildings built before 1978 and newer, larger apartment buildings constructed after 2007.1

Approximately 53 percent of D.C.’s rental units (73,136 units) and 76 percent of rental buildings (2,292 buildings) were built before 1978 and fall under rent-control. These buildings tend to be small (86 percent have fewer than 50 units) and offer lower rents due to their age and limited amenities.2

Since 2007, 201 new market rate rental apartment buildings were built in D.C., adding 34,117 more units (with the average building containing 150 units). Subsidized affordable housing production has also been strong: various programs have created an additional 20,486 units with committed affordability over the past decade.

These numbers underscore one striking feature of the District’s rental apartment stock: only 21 percent of all rental units are truly market rate, or without any government subsidies, affordability requirements, or rent restrictions.

There is no comprehensive data that tracks TOPA outcomes, including no systematic recording of sales, negotiated repairs, or settlements, making it difficult to assess whether the law is working as intended. To get a clearer picture, we looked at sales data and the formation of tenant associations (TAs), which are required for tenants to exercise their TOPA rights.

We found that half of all TA formations occurred in Wards 7 and 8. Smaller buildings dominated—71 percent of TA formations and 65 percent of transactions subject to TOPA occurred in buildings with fewer than 20 units. Expanding that to buildings with fewer than 50 units, the numbers rise to 88 percent of TA formations and 82 percent of transactions. Most of these buildings are more than 50 years old: 96 percent of TA formations and 94 percent of transactions occurred in properties built before 1978.

What are the concerns with current TOPA laws?

TOPA can help preserve affordability and facilitate repairs or improvements in older, smaller buildings, but it introduces delays, increases costs, and creates uncertainty—factors that discourage investor and lender interest in new developments and major renovations. Additionally, given current market conditions, TOPA struggles to reduce displacement or preserve affordability, even when mission-driven housing providers are interested in a property. These challenges stem from a lack of dedicated funding to support such projects, growing tenant arrearages (especially for affordable housing providers), and the inability of affordable housing providers to compete with cash offers to tenants.

Investor concerns

Sales data indicate that in buildings constructed after 2007, all transactions subject to TOPA occurred within the first 10 years of ownership. This likely reflects how these projects are financed. Large apartment buildings require significant upfront investment, with housing providers relying on equity partners who may hold up to 90 percent ownership in a market rate properties and 99 percent ownership in a Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) properties.

These investors typically exit within five to fifteen years to rebalance their portfolios,3 forcing the managing partner to recapitalize—a process that triggers TOPA under current law.4

Interviews with investors and brokers highlight how TOPA discourages financing for new developments and major rehabilitation projects:

- Delays and financial risk: Changing market conditions, prolonged negotiations, and potential lawsuits can disrupt transactions and tie up earnest money, causing financial losses.

- Equity partner challenges: Large projects have difficulty in attracting new investments or recapitalizing projects due to TOPA’s broad definition of a sale.

- Ownership change complications: Even partial ownership changes can trigger TOPA proceedings, delaying deals and adding costs.

- Refinancing obstacles: The Notice of Transfer requirement further complicates refinancing, making D.C. less attractive to investors compared to markets with clearer capitalization and exit strategies.

Challenges for tenant associations and housing providers

TOPA lacks dedicated funding to support TAs or to aid mission-driven housing providers in acquiring buildings. While TAs once played a more active role in purchasing buildings, they now face growing financing challenges, particularly for larger buildings. Even when acquisition loans are secured, permanent financing is increasingly difficult to access without dedicated support from the District.

Additionally, many properties purchased by TAs in the past have struggled financially due to underinvestment and inadequate capital reserves, raising concerns about the long-term viability of these transactions.

Cost and negotiation issues

TOPA negotiations often impose high costs on housing providers and investors. In some cases, securing the transfer of purchase rights requires large payouts to tenants—sometimes as much as $100,000 per unit—before a sale can proceed.

- These payments are not tied to long-term affordability or building improvements but instead serve as compensation for tenants.

- In some instances, cash payments can undermine affordable housing goals, as tenants may prefer cash offers rather than affordable housing deals that lack comparable financial incentives.

Lack of clear definition of success

As the process and outcomes of TOPA have evolved, its impacts have shifted away from its original intent of preventing displacement. Today, there is no widely accepted definition of what constitutes a successful TOPA outcome. Success could be measured by the preservation of affordable housing, displacement prevention, negotiated repairs, or financial payouts to tenants. Furthermore, there is no consideration of the potential impacts on new housing production.

To improve transparency and decision-making, the District should enhance data collection and reporting on TOPA-related actions, making information publicly accessible. Better data would allow for a clearer assessment of the law’s effectiveness and inform future policy adjustments.

Moving forward

TOPA has shifted from a tool designed to promote tenant ownership to a broader mechanism for negotiating repairs, building improvements, rent concessions, and cash settlements. While it has had successes, it also creates challenges that discourage housing investment in D.C.

Modernizing the law could help strike a better balance between preserving affordable housing and attracting new investment. Clearer guidelines for investors, alongside continued tenant protections, are especially crucial now. External pressures, such as high interest rates, and local policy challenges—like eviction regulations and limitations on Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) funds—have reduced investor confidence in the District. At the same time, rising foreclosure risks threaten existing housing providers.

A sharp decline in housing permits signals that production is set to plummet, further exacerbating the city’s housing shortage. To address these issues, elected officials must define clear objectives for TOPA, align the law with these goals, and ensure tenant associations and housing providers receive necessary support. A well-calibrated approach will help protect affordable housing while encouraging continued housing development and investment.

I. Introduction

When a rental building is sold5 in Washington, D.C., tenants have unique rights under the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA), a law embedded in the Rental Housing Conversion and Sale Act of 1980.6 Under TOPA, tenants can:

- Buy the building themselves, either as individuals or as a cooperative.

- Transfer their purchase rights to the original buyer or a buyer of their choice, potentially securing better terms for the tenants than the original offer.

- Negotiate for benefits such as repairs, rent concessions, or cash payouts before a sale closes.

TOPA emerged in response to a rental housing crisis. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, D.C. faced a surge in condominium conversions, particularly in Wards 2 and 37 where gentrification pressures were high.8 Between 1977 and 1980, 4.5 percent of the city’s rental stock converted to condominiums,9 a trend that accelerated to nearly 10 percent between 2000 and 2007.10 Meanwhile, new rental housing construction remained stagnant: between 1970 and 2000, only 7,800 net new rental units were added, a third of which are city-owned or tax-exempt. With limited housing production, conversions intensified competition for rental units and raised displacement risks.11

TOPA was meant to counteract these trends by giving tenants the first right to purchase their buildings, preserving rental housing and enabling tenant ownership through condominium and cooperative conversions. But over time, key amendments have reshaped its impact:

- 1995: Allowed tenants to assign their purchase rights to a housing provider, enabling properties to remain rentals.

- 2005: Expanded the definition of a “sale” to include internal ownership shifts and recapitalizations, making more transactions subject to TOPA.12

- 2018: Exempted single-family homes from TOPA, simplifying sales for individual property owners.

These changes have blurred the definition of a “successful” TOPA outcome. Potential measures of success include tenant inclusion in the sales process, tenant ownership, preservation of affordable housing, preservation of tenant tenure, negotiated repairs, or monetary payouts. These objectives often conflict, and without systematic data collection, it is unclear whether TOPA consistently achieves its intended goals.

TOPA’s impact on housing investment

TOPA has been most effective in older, smaller buildings, where tenants have successfully engaged in the process. But its application to larger, newer buildings is more controversial. The law can prolong sales, disrupt financing and recapitalization, and deter investment. This matters even more in today’s economic climate—higher interest rates and post-pandemic demographic shifts have weakened investor confidence in the District. Housing production is already suffering, and regulatory hurdles like TOPA may add further disincentives.

Recent research from the D.C. Policy Center finds that investor interest in D.C. has waned. Responses to the Quarterly Business Sentiments Survey conducted by the D.C. Policy Center’s Alice Rivlin Initiative for Economic Policy & Competitiveness indicate:13

- Businesses expect weaker growth in the District’s economy than the regional or national economies.

- The real estate sector is especially pessimistic.

- Many large investors and businesses reported in 2024 that they are unlikely to invest in D.C. in the next six months.

- Compared to pre-pandemic levels, businesses now place greater emphasis on regulatory and tax conditions when making investment decisions.

While TOPA is just one piece of the District’s regulatory framework, its impact extends beyond slowing transactions for existing buildings. Interviews suggest that institutional investors hesitate to finance new housing projects in D.C. due to concerns over TOPA-related delays and potential lawsuits when they eventually need to rebalance their portfolios. This, in turn, makes it harder for housing providers to secure funding for new development.

What’s next for TOPA?

Reforming TOPA could better align the law with current policy goals—preventing displacement, preserving affordability, and ensuring necessary repairs—while also providing clarity and predictability for developers. The challenge is striking the right balance: preserving tenant protections without discouraging the investment needed to produce more housing. Without adjustments, the District risks exacerbating its housing shortage while further eroding investor interest.

II. The origins, evolution, and the process of TOPA

TOPA was enacted in 1980 in response to minimal rental housing production and a wave of rental-to-condominium conversions. This provided existing tenants very little opportunity to find an affordable rental in the city if they had to leave their current buildings. Legislative reports from both the law’s original passage and subsequent amendments indicate that TOPA’s primary goal was to protect lower-income and elderly tenants from displacement during property sales.14

Originally, TOPA allowed tenants in rental apartment buildings to match third-party offers and purchase their units under favorable terms. This gave tenants more control over the sale process and strengthened their negotiating position.15 While there is no publicly available data on the number of tenant purchases or tenant associations formed, accounts suggest that cooperative formations and tenant purchases were initially more common. However, in recent decades, tenant purchases have declined—likely due to weaker community ties within buildings, rising purchase prices, and limited financing options.

How TOPA has changed

Over time, TOPA has undergone major amendments that have shifted its outcomes including allowing tenants to assign their purchase rights to housing providers rather than purchasing the building themselves (1995), and redefining what constitutes a “sale” to include recapitalizations and certain internal ownership changes (2005).

Importantly, in 2018, The D.C. Council exempted single-family homes from TOPA to simplify sales for individual homeowners. Previously, all single-family home sales were subject to TOPA, though under slightly different rules and timelines than larger rental properties. However, the Council found that applying TOPA to single-family homes did not effectively achieve its original goals of expanding homeownership for lower-income tenants, preserving affordable rental housing, or preventing displacement.

Several factors contributed to the decision to remove single-family homes from TOPA, many of which reflect broader challenges within the program:

- Tenants rarely purchased the homes, largely due to high costs.

- Many tenants used the full TOPA timeline to negotiate cash settlements rather than pursuing homeownership.

- Some individuals falsely claimed TOPA rights by misrepresenting themselves as relatives or caregivers of tenants.

- There was little interest from third-party buyers in purchasing single-family homes while keeping existing tenants.

- Community-based organizations (CBOs) lacked the resources to support tenants through the process.

- Fewer homeowners were willing to rent out single-family properties due to concerns about delayed sales and legal complications.

The Committee report stressed that TOPA was never intended to serve as a tool for wealth transfer to tenants or to unfairly interfere with private home sales. It also noted that applying TOPA to single-family homes distorted the real estate market by shifting equity from homeowners to tenants who were both fortunate enough to live in a home being sold and knowledgeable about the law.16

Additionally, many large-scale housing projects, including those supported by the D.C. Council, have been exempted from TOPA over the years. Exempted projects including notable affordable developments such as Jubilee Maycroft,17 Anna Cooper House,18 Karin House,19 N Street Village,20 Paul Laurence Dunbar Apartments,21 and Jeremiah House and Shalom House.22 One additional exemption is the Housing in Downtown Program (HID) which exempts new development downtown from TOPA requirements for the first sale within 10 years of the final Certificate of Occupancy.23

Today, nearly 95 percent of sales where a tenant association (TA) forms result in an assignment of purchase rights, meaning most properties remain rentals.24 (For a timeline of significant changes to TOPA, see Appendix.)

Four possible outcomes of a TOPA sale

Under the current law, there are four possible outcomes of a TOPA sale:

- Tenant purchase and condominium conversion:

- Tenants buy the building and convert units into condominiums.

- A condominium association takes over management and maintenance.

- Tenant purchase as a limited equity cooperative (LEC):

- Tenants collectively purchase the building as a cooperative, sharing ownership.

- The cooperative manages the property and often imposes resale restrictions to maintain affordability.

- Assignment of rights (95 percent of cases):25

- Tenants assign their purchase rights to the original buyer or a developer of their choice.

- In exchange, tenants may negotiate building repairs, rent concessions, or cash payments.

- Monetary payments are common and are typically split between the TA and legal representation (if applicable).26

- No tenant association forms:

- If tenants do not register a TA within 45 days, the sale proceeds as a standard transaction.

The TOPA process: Stakeholders, timelines, and legal considerations

TOPA transactions involve multiple participants, including:

- Sellers, buyers, and tenants organized as a TA;

- Alternative buyers to whom tenants might assign their rights;

- Community-based organizations (CBOs) that help tenants organize;

- The D.C. Office of the Tenant Advocate, which informs tenants of their rights and provides legal aid;

- Financial institutions and D.C. government agencies that may provide financing for tenant purchases;

- Lawyers representing either the TA or the building owner; and

- Title companies, which ensure compliance with TOPA procedures before approving a sale.

TOPA requires strict adherence to procedures and timelines. Failure to comply may result in title companies refusing to insure the property or legal challenges. TOPA involves multiple steps:

- Offer of Sale notification. Before selling, transferring, or recapitalizing almost all rental buildings with more than five units,27 an owner must issue tenants an Offer of Sale that announces the owner’s intent to sell, transfer, or recapitalize more than 50 percent of the interest in the building. This document includes:

- A third party offer price (or bona fide price);28

- The terms of the sale;

- A statement that the tenants have the first right of refusal to purchase and of their TOPA rights;

- Sources of assistance to tenants; and

- A statement that the owner will provide tenants with financial information on operations and maintenance upon request.

- Tenant Association formation (first 45 days). Tenants must form a TA and submit a registration application to the building owner and the D.C. Department of Housing and Community Development’s (DHCD) Rental Conversion and Sale Division.

- The TA must represent at least 51 percent of heads of household, excluding:

- Households where no member has lived in the unit for at least 90 days; or

- Households where any member was an employee of the building owner within the past 120 days.29

- All tenants may join the TA, but once it is registered, the TA becomes the sole entity with exclusive TOPA rights under the law.30

- The TA must represent at least 51 percent of heads of household, excluding:

- Decision to purchase or assign rights (next 120–360 days):

- The TA has 120 days to assign its rights to a buyer or register its intent to purchase the building.31

- If the TA moves forward with an intent to purchase:

- The owner can request a deposit of up to 5 percent of the purchase price, refundable if the sale does not go through or if the TA assigns its rights to a buyer.

- The TA then has another 120 days to finalize financing (180 days for Limited Equity Cooperatives).

- If the TA secures a letter of interest from a lender, the deadline extends to 240 days.

- If the TA fails to meet these deadlines, its TOPA rights expire.

- Finalization or restart of the process:

- If no sales contract is signed within 360 days of the initial Offer of Sale, the process must restart.

- Legal challenges, ranging from major contract disputes to minor procedural violations, can extend the timeline indefinitely.32

The impact of TOPA on housing transactions

In practice, TOPA can delay sales by up to 420 days. One estimate found that sales involving a registered TA were delayed by an average of 5.3 months.33 However, if legal disputes arise, transactions can be stalled for years. Such complaints, which may range from major contract disputes to minor procedural issues, can postpone sales for years while litigation is ongoing.

It is also important to note that TOPA is not triggered solely by building sales—it applies to:

- Recapitalizations

- Refinancing

- Extensions of Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) deals

- Certain ownership transfers, even when control of the building remains unchanged

III. The landscape of rental housing in rental apartment buildings in the District of Columbia

TOPA laws are broad and apply to all sales of rental apartment buildings. Therefore, it is important to understand the landscape of rental housing in the District to fully assess the impact of TOPA.

Rental housing production in D.C. slowed dramatically after 1978, just before the enactment of TOPA, and did not resume at a significant scale until 2007. As a result, the city’s rental housing stock is largely divided into two categories: older, smaller buildings that are subject to rent control and newer, larger buildings constructed since 2007. Rental buildings built in the last 20 years are generally much larger than those built before 1978 and are concentrated in specific areas of the city.

Most of D.C.’s rental housing—63 percent of all units (87,866 out of 138,392) and 87 percent of all buildings (2,621 out of 3,006)—was built before 1978. Nearly all of these older buildings (86 percent) contain fewer than 50 units and are subject to the rent control regulations established in 1985. Under these regulations, annual rent increases for occupied units are restricted. To be included in the rent-controlled stock, a building must have received its construction permit before 1976. This means many properties completed in 1976 and 1977 are also covered. For simplicity, this analysis uses 1977 as the cutoff to estimate which buildings fall under rent control.

Between 1978 and 2006, very little rental housing was built, accounting for only 5 percent of the total rental stock. Several major policy changes during this period reshaped the housing market. The Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA), enacted in 1980 as part of the Rental Housing Conversion and Sale Act, was amended multiple times, including changes in 1989, 1995, and 2005 that expanded the definition of a sale and allowed tenant associations to transfer their purchase rights to housing providers while keeping the units as rentals. Other key policies included the introduction of rent control under the Rental Housing Act of 198534 and the creation of the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) through the Tax Reform Act of 1986.35

Housing permits began to increase again in 2005, with substantial production starting in 2007. Over the past 17 years, 42,980 rental units—31 percent of the total rental stock—have been built in 300 buildings, representing 10 percent of all rental properties. Since 2007, new construction has primarily consisted of large buildings, with 50 percent of buildings containing 100 or more apartments and 15 percent in buildings containing 50 to 99 units. This shift toward larger, high-cost developments has fueled the creation of entirely new residential and mixed-use neighborhoods, including the Capital Riverfront, NoMa, Mount Vernon Square, The Wharf, and more recently, Union Market. These projects have been heavily supported by institutional investment. In contrast, only 14 percent of rental buildings constructed before 1978 contain 50 or more units.

Current stock of multifamily rental apartments in D.C.

As of 2024, there are 3,006 apartment buildings in the District of Columbia, containing 138,392 rental units.36 While these buildings represent only 3 percent of all housing structures in the city, they account for 69 percent of all rental housing units.37 These buildings are spread across the city, with the highest concentrations in Wards 7 and 8, which together house 46 percent of all rental apartment buildings with five or more units, though they contain only 26 percent of the total units. Ward 3, which is primarily zoned for single-family homes, has the smallest share of these buildings.

The District’s rental apartment stock is regulated differently depending on when buildings were constructed, with key policies including rent control and inclusionary zoning (IZ).

Approximately 53 percent of all rental units—73,136 units in 2,292 buildings—were built before 1978 and are subject to rent control, which limits annual rent increases for occupied units.38 Additionally, public tax records show 8,849 rental units in publicly owned buildings built in this period, though some of these units are not in use due to disrepair.39

Since 2015, the D.C. government has reported the creation of 20,486 affordable units through various programs, with another 5,077 units under construction and 11,334 more in the pipeline.40 Our dataset specifically identifies 8,329 units in 107 buildings developed with funding from the District’s Housing Production Trust Fund.41 Another 10,100 units in 61 buildings receive subsidies such as Housing Choice Vouchers or tenant-based rent supplements.42 While these buildings advertise market-rate or rent-controlled rents, tenants with subsidies pay reduced rates. Regardless of when these buildings were constructed, subsidized units are not subject to rent control.

The remaining 25 percent of rental units in buildings with five or more units are classified as market-rate. This includes 247 market-rate buildings with 34,117 units. However, about 4,400 of these units are subject to inclusionary zoning (IZ) requirements.43 This leaves only 21 percent of all rental units (29,717 units) as truly market rate, or without any rent restrictions, government subsidies, or affordability requirements.

Affordability of units in rental apartment buildings

Rental prices in D.C. vary significantly across different buildings and market segments. CoStar, a major source for rent data, provides information on approximately 1,808 buildings, covering 94,000 units. This represents about 60 percent of buildings with five or more units and 68 percent of all rental units in such buildings. Of these, detailed rent information is available for 1,077 buildings (36 percent of all buildings) and 83,858 units (61 percent of total units).

According to this data, median rents in D.C. are:44

- $1,580 for studios;

- $1,597 for one-bedroom units;

- $1,960 for two-bedroom units; and

- $2,108 for three-bedroom units.

Rent variability across market segments

The available rent data tends to overrepresent subsidized units, which may result in reported median rents that are lower than actual market-wide averages. Rent data is most frequently available for buildings that accept vouchers and tenant-based subsidies, which account for 10 percent of the rental stock. In this segment, data is available for nearly all units in 9 out of 10 buildings.

For other types of subsidized housing, including properties funded through the Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF) and Section 8, rent information is generally more accessible than for market rate buildings, except for publicly owned housing where data is less comprehensive.

Rent data coverage varies across different types of buildings:

- Rent-controlled buildings: Data is available for 36 percent of buildings, covering 60 percent of units in this segment.

- Market-rate buildings: Data is available for 39 percent of buildings, covering 53 percent of units in this segment.

Because of these discrepancies, reported rent figures may not fully reflect market conditions, particularly in non-subsidized buildings.

Rents vary significantly across different market segments. For example, the median rent for a market-rate studio is $1,992, which is about 30 percent higher than the median rent for a rent-controlled studio. In contrast, studios in buildings funded by the Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF) or that accept Section 8 vouchers typically rent for 25 percent less than rent-controlled units. Studios in publicly owned buildings have even lower rents, averaging 50 percent below those in rent-controlled buildings.

The rent gap between market rate and rent-controlled units widens as unit sizes increase. A market-rate one-bedroom rents for 62 percent more than a rent-controlled one-bedroom, while a market-rate three-bedroom—though relatively uncommon—can rent for 2.6 times the rate of a rent-controlled three-bedroom. At the same time, the relative rent discounts for publicly owned and subsidized units shrink as unit sizes increase.

While rental price differences are often associated with policy programs, factors such as building age, amenities, and location play a larger role in determining rents. Rent-controlled buildings are older and may lack the high-end features and prime locations of newer market-rate properties, contributing to significant price differences beyond just regulatory restrictions.

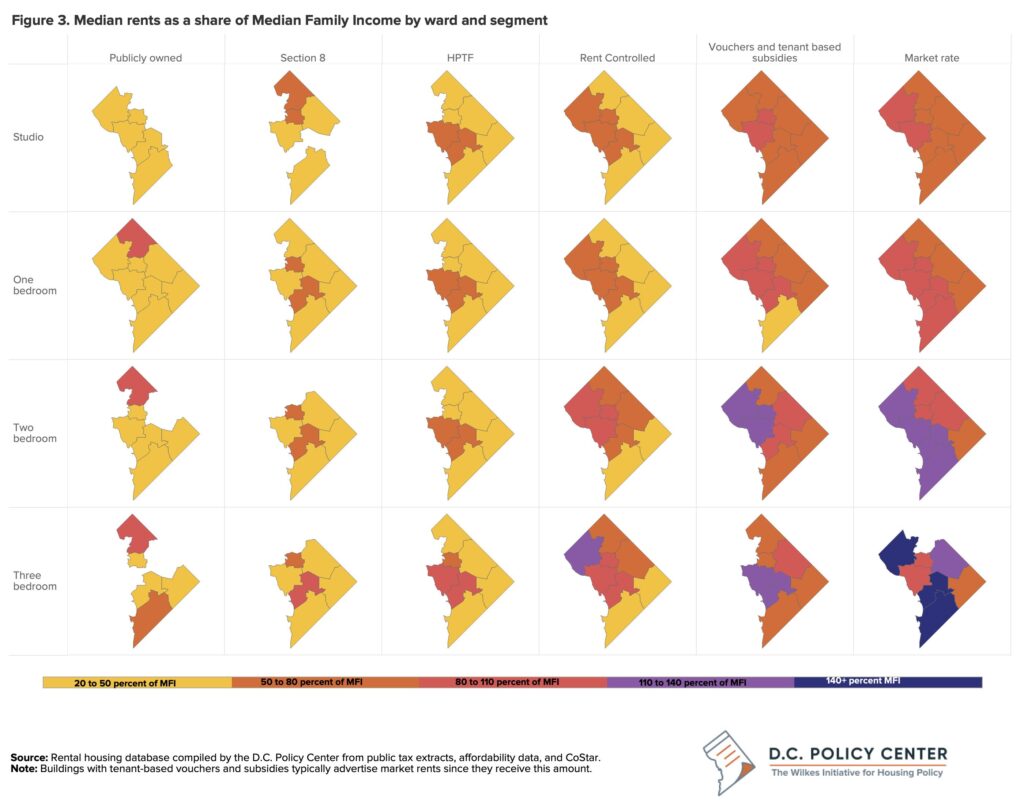

Ward-level rent analysis

A ward-level breakdown shows how rental prices vary across different market segments, influencing affordability. Across all eight wards, median rents in publicly owned buildings, Section 8 properties, and buildings funded by the Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF) remain affordable for households earning at or below 80 percent of the Median Family Income (MFI). These units, totaling just over 20,000, are concentrated in specific areas (represented by yellow and orange areas on the maps). However, as unit sizes increase, the availability of these more affordable buildings declines, making it harder for larger households to find options within this price range.

Rent-controlled buildings are widely distributed throughout the city and provide about 67,500 studios and one-bedroom units that are affordable to households earning 80 percent or less of MFI.

In contrast, market-rate units are generally more expensive. Outside of studios, most market-rate apartments require incomes between 80 and 110 percent of MFI, and in many neighborhoods, the income needed to afford these units is significantly higher. This pricing dynamic makes it particularly difficult for middle-income and lower-income households to secure larger units without rental assistance.

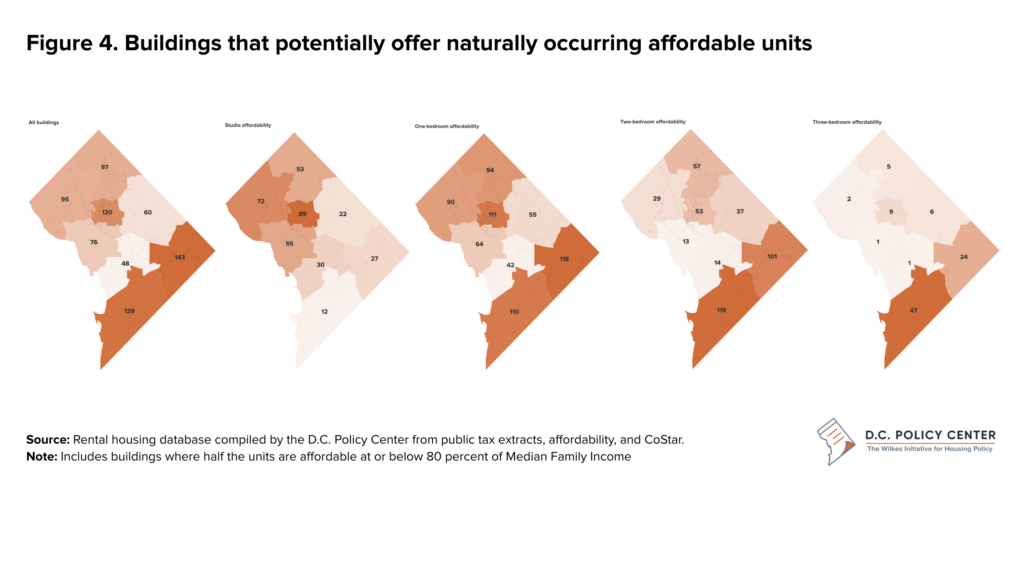

Affordability without subsidies

There are an estimated 773 buildings in D.C. where rental units are naturally affordable—meaning they are unsubsidized and have no rent restrictions—for households earning 80 percent of the Median Family Income (MFI). These buildings are not evenly distributed across the city. About 50 percent are located in Wards 1, 7, and 8, while another 25 percent are in Wards 3 and 4. Wards 5 and 6 have the smallest shares of naturally affordable housing.

Most of these buildings primarily offer smaller units. In 82 percent of cases, the only affordable options are studios and one-bedrooms. Two-bedroom units are available in about half of these buildings, while three-bedroom units are much rarer, found in fewer than 12 percent of naturally affordable properties.

The overwhelming majority of buildings—738 buildings, or 95 percent—were built before 1978 and are rent-controlled. Only 5 percent were constructed since 2007, reflecting a sharp decline in the availability of naturally affordable housing in newer buildings.

These buildings also tend to be small to mid-sized. About 70 percent (552 buildings) contain fewer than 50 units, while only 14 percent (110 buildings) have 100 or more units. Large, newer buildings are particularly scarce. Among properties built since 2007, only 20 buildings with more than 100 units are naturally affordable, representing less than 2.5 percent of all unsubsidized affordable buildings in the city.

Multifamily market sales trends in the region

One common argument against TOPA is that it reduces both sales volume and property values. To assess these claims, we analyzed real estate trends in submarkets across the D.C. metropolitan area that contain at least 6,000 multifamily units.45

Data from CoStar indicate that since 2000, multifamily inventory has grown by more than 50 percent in D.C., Maryland, and Virginia. Asset valuations have followed a similar trajectory, with declines during the Great Recession and again starting in 2022, as the D.C. metropolitan area faces increased competition from other regions for housing demand and investor interest.

However, sales volume in D.C. has declined sharply since 2015. Several factors may be contributing to this trend, including:

- More attractive investment opportunities in suburban markets, where per-unit values may offer better returns.

- The reduced importance of commute times due to telework, shifting demand to suburban areas.

- Regulatory challenges such as TOPA, which can complicate and delay property transactions.

Diverging trends: Sales volume vs. asset valuations

A comparison of sales volume and overall asset valuations highlights shifting trends. In the early 2000s, D.C.’s annual sales volume was about 1 percent of total asset values, largely due to limited new construction. That began to change in 2010, when the construction boom increased available inventory. Between 2010 and 2018, sales volume as a share of asset valuations rose to 3 percent, bringing D.C. in line with Maryland and Northern Virginia submarkets.

However, since 2018, D.C.’s sales volume relative to its asset values has declined and is now half the levels seen in Maryland and Virginia. This suggests that while the overall value of D.C.’s multifamily market remains strong, fewer properties are being sold relative to the total value of the asset base.

Potential revenue impact

If D.C. aligned its sales volume with Maryland and Virginia levels, it could generate significant additional revenue through deed transfer and recordation taxes. Between 2019 and 2023, D.C.’s annual sales volume averaged $1.06 billion, producing $30.8 million in deed transfer and recordation taxes.

If sales volume as a share of asset values increased to match that of suburban submarkets, total sales would more than double, generating an additional $37 million in tax revenue.46 This underscores the potential economic impact of policies that encourage easier property transactions in the District.

IV. What kinds of buildings have gone through TOPA?

Accessing, analyzing, and interpreting data on TOPA transactions is difficult due to limited public reporting and restricted data access. The D.C. Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) publishes a weekly report listing Offers of Sale and Tenant Association (TA) registrations, but detailed building-level data are available only to D.C. government employees.47 No publicly accessible reports track key outcomes such as tenant purchases, assignment of rights, negotiated repairs, or affordability covenants.

In November 2023, the Coalition for Nonprofit Housing and Economic Development (CNHED)—now called The Coalition—released a study analyzing 354 TOPA transactions from 2006 to 2020.48 While the report provided some insights into TA formation, assignment of rights, and affordability covenants, it lacked building-specific details. The D.C. Policy Center requested access to the underlying data for further analysis but was denied.

To better understand the types of buildings involved in TOPA transactions, the D.C. Policy Center obtained sales and transaction data from Greysteel, a real estate investment firm. Greysteel compiled:

- CoStar sales data from January 2012 to February 2023;

- TA registration data from DHCD weekly reports (starting August 2016) and internal records dating back to 2013;49 and

- Data verification through interviews with housing providers.

Despite these efforts, determining actual outcomes of TOPA transactions through available data remains nearly impossible due to the way the data are structured. Even in cases where TOPA led to tenant purchases or assignment of rights, the available data does not clarify:

- Which of these outcomes occurred;

- Whether affordability restrictions were introduced or preserved;

- If repairs were negotiated; or

- Whether tenants received cash settlements.

This lack of transparency makes it difficult to evaluate whether TOPA successfully prevents displacement, preserves affordable housing, or secures financial or repair benefits for tenants.

Adding to the complexity is the role of voluntary agreements, which were allowed under D.C.’s rent control laws until a 2020 moratorium. These agreements enabled landlords to propose rent increases for new tenants in exchange for building improvements, provided 70 percent of existing tenants approved. They offered an alternative method for tenants, sellers, and buyers to negotiate affordability and repairs outside of the TOPA process.

While there is no universal agreement on what constitutes a successful TOPA transaction, one common requirement is the formation of a Tenant Association (TA). Without a TA, tenants cannot purchase a building, assign rights, or negotiate for repairs or financial settlements.

The dataset used in this analysis includes 419 transactions covering 16,962 units where TOPA would have applied.50 Among these, 158 transactions (representing 7,409 units) were confirmed to have a registered TA, indicating tenant engagement in the process but not necessarily providing clarity on final outcomes.

Prevalence of TOPA transactions in smaller, rent-controlled buildings

Between 2012 and 2023, most transactions subject to TOPA involved smaller, rent-controlled buildings. Among the 419 applicable transactions covering 16,962 units, 65 percent took place in buildings with fewer than 20 units, and 82 percent were in buildings with fewer than 50 units. Nearly all of these smaller buildings were built before 1978, making them subject to rent control—99 percent of buildings with fewer than 20 units and 97 percent of those with 20 to 49 units fall into this category.51

The 394 transactions in rent-controlled buildings in this period represent about 17 percent of the total rent-controlled building stock. In contrast, only 19 transactions involved buildings constructed since 2007, accounting for just 7 percent of all buildings in that segment.

Ownership trends also varied by building age. In more than half of all transactions (226 out of 419), the seller had owned the property for over a decade—but this was almost exclusively the case for older, rent-controlled buildings. For buildings constructed since 2007, every transaction occurred within 10 years of initial ownership.

This pattern likely reflects the financial structure of large, newly constructed buildings. These developments often require substantial upfront investment, with institutional equity partners holding 90 percent of ownership equity. Institutional investors typically operate on a five to fifteen year investment cycle, leading to property recapitalizations that trigger TOPA proceedings, even when the original developer remains in control.52

TA formations are also concentrated in smaller, rent-controlled buildings

Among the 158 confirmed registered tenant associations (TAs), covering 7,409 units, 71 percent occurred in buildings with fewer than 20 units, and 88 percent were in buildings with fewer than 50 units. Larger buildings were far less likely to see TA formations—only 32 TAs formed in buildings with more than 50 units.

TA formations were overwhelmingly concentrated in older, rent-controlled buildings. More than 96 percent formed in properties built before 1978. In contrast, only five TA formations occurred in buildings constructed since 2007, and just one TA formed in a building constructed between 1978 and 2006.

Decline in TA formations due to financing challenges

Tenant association (TA) formations have declined significantly in recent years. Discussions with tenant lawyers and organizations that fund TOPA acquisitions indicate that banks are becoming increasingly hesitant to finance these transactions, even when an affordable housing provider is assigned TOPA rights. This growing reluctance to provide financing may be a key factor behind the declining number of new TA formations.

Sales and TA formations concentrated in Wards 7 and 8

Half of all sales and TA formations took place in Wards 7 and 8, where property values were the lowest. Between 2021 and 2023, the average sale price per unit in these wards was $123,000, which was $60,000 lower than the next most affordable ward, Ward 4.

In contrast, Wards 3 and 6 had the highest per-unit prices—$311,000 and $354,000, respectively—and accounted for only 4 percent and 6 percent of all sales.

Ward 4 had the highest rate of TA formations, occurring in 47 percent of all sales. This is likely due to the high concentration of smaller apartment buildings, which make TA formation and tenant purchases more practical compared to larger, more expensive properties.

V. Assessing the impact of TOPA laws in D.C.’s current housing market

D.C.’s high housing costs have raised concerns about gentrification and displacement. To stabilize prices and improve the city’s housing supply, policymakers must focus on both preserving affordable housing and promoting new market-rate development.

The rise of remote work has reshaped housing demand, weakening the traditional link between where people live and work. Unlike in the past, many people now move to D.C. for housing rather than jobs, making housing a key economic development tool. To attract and retain residents, the city needs a diverse and abundant housing supply at various price points and across different neighborhoods.

However, even before the pandemic, demand for D.C. housing was softening, driven in part by competition from lower-cost states with fewer land-use restrictions and housing regulations. This shift has reduced investor interest across all segments of the market, making it harder to finance new development, preserve existing affordable housing, and sustain overall affordability.

These challenges not only affect today’s housing market but could also worsen long-term affordability. The supply of naturally occurring affordable housing in the future depends on robust market-rate production today, just as today’s expensive housing stock is a direct result of limited construction between 1970 and 2005.

The role of TOPA in D.C.’s housing market

The Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) is a key part of D.C.’s housing regulations. While it is not the sole factor behind declining investor interest and slowing housing production, it does introduce uncertainty into the market. Modifying TOPA could provide greater predictability for investors and developers while impacting only a small share of transactions.

TOPA has been in place for over 40 years with mixed results. It has helped preserve affordable housing by giving tenants significant bargaining power, particularly in older, smaller buildings. However, the process is often lengthy and complex, discouraging investment. Extended sale timelines create financial uncertainty, especially in fluctuating markets, and recapitalization often triggers TOPA, making it harder to secure financing. These challenges make multifamily investment in D.C. less attractive, potentially limiting the city’s future housing supply.

TOPA’s early success: creating tenant ownership

During the 1980s and 1990s, TOPA played a key role in expanding tenant ownership, particularly in rental buildings that were being converted to condominiums. It empowered tenants to either purchase their units individually, or collectively by forming cooperatives. The extended timelines provided tenants time to organize, secure financing, and learn how to manage buildings.

However, tenant ownership has become much less common in recent decades. Attorneys and lenders report that purchases are now rare due to lack of lender interest in financing tenant purchases. Interviewees noted barriers including a lack of community cohesion and management experience among tenants and high purchase prices. Unfortunately, no publicly available data exists to verify the decline in tenant purchases, making it difficult to assess this trend quantitatively.

TOPA’s current success: a negotiating tool in older, smaller, buildings

In 95 percent of transactions where a Tenant Association (TA) forms, tenants do not purchase their buildings. Instead, they assign their purchase rights to the original buyer or another housing provider, allowing the property to remain as a rental. As a result, TOPA now functions primarily as a negotiation tool to improve building conditions, secure repairs, add affordability protections, or negotiate financial settlements for tenants.

Research from the Coalition found that:

- 84 percent of sales occurred in buildings more than 25 years old;

- 73 percent of TA registrations were in buildings built before 1970;53

- Half of all buildings involved in TOPA transactions contained fewer than 15 units.

Greysteel data supports these findings, showing that:

- 94 percent of transactions subject to TOPA were in buildings built before 1978;

- 96 percent of TA formations were in buildings over 50 years old (built before 1978);

- 71 percent of TA formations were in buildings with fewer than 20 units; and 88 percent were in buildings with fewer than 50 units.

Most buildings where a TA formed are over 50 years old and under rent control. These properties tend to have below-market rents, making tenant purchases and affordable housing deals more feasible. According to CNHED, approximately 40 percent of the units where there was an assignment of rights of tenant purchase resulted in preserved or newly added affordable units, often through Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) financing, Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF) subsidies, D.C. Housing Finance Agency (DCHFA) loans, or a combination of those. Another 40 percent of these transactions did not add affordability restrictions54 but remained under existing rent control protections.55

Many buildings that go through the TOPA process are older and require repairs. Negotiations can be an effective tool for ensuring building preservation and improvements. According to CNHED data, 78 percent of the units where tenants negotiated either a purchase or assignment deal—almost all of which were in buildings with fewer than 15 units—were renovated or repaired.56

However, there is no publicly available data tracking the outcomes of TOPA negotiations, including how often repairs are secured as part of the process. There is also no information on whether similar repairs would have taken place in the absence of TOPA negotiations. This lack of information makes it difficult to assess the effects of TOPA on housing conditions.

Findings from stakeholder interviews

The D.C. Policy Center conducted structured interviews with 13 stakeholders about their experiences with the implementation of TOPA laws. Participants included market rate and affordable housing providers, investors including those with a mission to preserve affordability, brokers, tenant and landlord attorneys, and title agents. The following takeaways are based on comments, observations and suggestions gathered by stakeholder interviews, supported by the analyses presented in this report.

TOPA creates uncertainty that may discourage investment in multifamily rental housing.

Interviews with brokers and investors indicate that uncertainty surrounding TOPA has made investors hesitant to finance new development and major rehabilitation projects in D.C. One of the biggest concerns is the difficulty of exiting the market.

Major equity partners typically invest for a set period after which they exit the project, requiring the property to secure new financing or new equity partners. This process triggers TOPA, adding layers of complexity to the transaction.

Extended timelines and financial risk

TOPA’s lengthy process creates significant financial risks for building owners and buyers.

- On average, TOPA proceedings delay transactions by 5.3 months, but in some cases, they can stretch up to 420 days.57

- Interest rate fluctuations during this period can make financing more expensive or cause deals to fall apart entirely.

- Buyers must place earnest money in escrow, which remains inaccessible during the TOPA process. This ties up capital, making D.C. less attractive to investors, especially during high-interest-rate periods when funds could be invested elsewhere for better returns.58

Legal challenges and uncertainty

Legal disputes can prolong transactions for years, even after a deal has been negotiated.

- Any individual tenant59 60 can allege non-compliance with TOPA, delaying the sale indefinitely.

- In some cases, a single tenant or a small group has threatened legal action even after the tenant association (TA) has reached an agreement with the purchaser.61 62

- This uncertainty makes title companies hesitant to insure transactions and can lead to exploitative lawsuits, as attorneys only need to find one tenant willing to contest the process to initiate litigation.

Impact on investment

These challenges make D.C. multifamily housing less attractive to investors compared to markets with clearer exit strategies and less regulatory risk. The combination of long delays, financing uncertainty, and legal exposure discourages investment in D.C. multifamily housing, potentially reducing new housing supply and rehabilitation efforts in the city.

TOPA negatively impacts recapitalizations, transfers of interest, and internal ownership changes

TOPA creates uncertainty around recapitalizations and transfers of ownership interest. Large equity partners and institutional investors, who often own 90 percent or more of the equity in a building, typically operate on an investment cycle of five to fifteen years. When their investment period ends, a property must secure new financing or equity partners to recapitalize. Under current TOPA laws, this routine recapitalization process triggers TOPA proceedings,63 even if control and management of the building remain unchanged.64

How TOPA affects recapitalizations

Previously, TOPA was triggered only when 100 percent of a building’s ownership interest changed. However, a 2005 amendment lowered the threshold to 50 percent to prevent staggered transfers designed to avoid tenant involvement.65 This can create barriers for buildings to securing financing needed to finance substantial repairs or renovations.

How TOPA affects partial transfers and ownership restructuring

Even partial ownership transfers below 50 percent can lead to delays and legal risks. When this happens:

- The seller must file a Notice of Transfer, informing tenants that TOPA does not apply.

- Tenants then have 45 days to register a claim and another 30 days to file a legal complaint, extending uncertainty for up to 90 days.

- This statutory Notice of Transfer period can be exploited with frivolous lawsuits, further discouraging investment in the D.C. housing market.

A key example of TOPA-related legal delays occurred in the 2019 case of Williams v. Kennedy.66 In this case, the D.C. Court of Appeals ruled that TOPA does not apply when one partner buys out another, as long as no new partner enters the ownership structure. However, the lawsuit delayed the transfer of interest for over two years, even though the case ultimately confirmed the transaction was not subject to TOPA. While this is legal statute, similar cases have been held up by litigation. This creates uncertainty for investors and housing providers who fear costly litigation and prolonged delays, even when transactions comply with existing laws.

The market consequences of investor concerns

By complicating recapitalizations and ownership transfers, TOPA discourages long-term investment in D.C.’s multifamily housing market. The risk of litigation, financial losses, and regulatory hurdles makes D.C. less attractive to investors compared to markets with clearer and more predictable exit strategies. This could limit new housing development and rehabilitation efforts, further straining the city’s already tight housing supply. These impacts are partly evidenced by lower multifamily sales volume adjusted for asset size in D.C. compared to other large multifamily markets elsewhere in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area.

TOPA creates challenges in affordable housing preservation

Two main ways through which TOPA has helped preserve affordability are purchases by tenants and assignment of rights to mission-driven housing providers with commitment to preserving long-term affordability. One of the biggest limitations of TOPA is the lack of dedicated funding for such purchases. For example, in the past, tenant associations (TAs) were able to purchase buildings more frequently, but today, they struggle to secure financing, especially for larger buildings.

Purchasing a building typically requires:

- Short-term financing (acquisition loans) to cover the initial purchase.

- Long-term financing to replace the acquisition loan within three to four years.

Currently, short term loans are provided by the Housing Preservation Fund, which is partially funded by the city and managed by LISC, Capital Impact Partners, and the Low Income Investment Fund (LIIF).67 Long-term financing typically comes from sources like the Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF) and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program.

However, for TA purchases, securing long-term financing has become increasingly difficult, even when tenants successfully obtain acquisition loans. As a result, many HPF loans originally intended to be short-term have not been repaid and now function as long-term mortgages. This leaves the Housing Preservation Fund with fewer available resources for new tenant purchases.

Financial struggles of tenant-owned buildings

Many buildings purchased by TAs and converted into condominiums or cooperatives in past decades are now facing financial difficulties due to:68

- Undercapitalization, leaving little room for major repairs.

- Unpaid condo dues, making it harder to maintain buildings.

- Lack of reinvestment, leading to deteriorating conditions over time.

Smaller buildings (typically under 50 units) tend to navigate the TOPA process more successfully, while larger tenant-led purchases often face both financial and community management challenges. Insufficient capital and unpaid dues can contribute to building deterioration, making long-term affordability and sustainability more difficult.

One way to address this issue is by allowing mission-driven housing providers to use HPTF resources to purchase these buildings. This approach could:

- Preserve affordability more effectively than relying on tenant-led purchases.

- Speed up deal closures, reducing uncertainty in transactions.

- Achieve a lower per-unit cost than constructing new affordable housing.

Impact of TOPA on LIHTC deals

TOPA can disrupt the financing of LIHTC properties, making it harder to keep affordable housing covenants in place. LIHTC projects require a minimum 30-year affordability period, split into an initial 15-year compliance period, followed by a 15-year extended use period. After 15 years, owners have the option to:

- Convert the property to market rate

- Apply for a Qualified Contract (QC), allowing the Housing Finance Agency (HFA) to find a buyer willing to maintain affordability. If a buyer is found, the property remains under LIHTC restrictions. If not, it is released from affordability requirements after a three-year transition period.

Although the D.C. Council passed a TOPA exemption for LIHTC resyndication at 15 years, it requires the original owner to stay on the project, preventing them from receiving federal tax credits.69 Additionally, while investors are exempt from TOPA when they enter the market, they are not exempt from TOPA when they exit. This discourages long-term preservation of affordable housing and makes it harder to secure necessary financing.

TOPA’s broader impact on housing costs

Another challenge with TOPA is that it is not specifically targeted toward low-income tenants, allowing any resident of a multifamily building to benefit. Additionally, negotiated TOPA deals often increase costs for future tenants by excluding them from affordability protections.

Housing costs can increase due to negotiated cash payments in exchange for a TA assigning their purchase rights. These payments can be as high as $100,000 per tenant.70 Some housing providers view these payments as an extra cost or “tax” on transactions, especially in market-rate buildings where TAs are unlikely to secure financing or an alternative buyer. These payments do not contribute to affordable housing development or building repairs. In fact, these payments can price out affordable housing developers who cannot match the cash offers of market-rate developers.

Lack of consensus about what constitutes a success under the law

There is no clear agreement on the intended purpose of TOPA or what qualifies as a successful outcome. Success could be measured by a variety of factors, including:

- Preserving affordable housing,

- Preventing tenant displacement,

- Negotiating building repairs, or

- Providing financial payouts to tenants.

What is considered a successful outcome today may differ significantly from the original intent of the law. Over time, the TOPA process and its impact have evolved, leading to shifting interpretations of its purpose.

Diverging views on tenant payouts

Interviews with stakeholders reveal a deep divide over the appropriateness of tenant payouts.

- Many tenant advocates view financial settlements and payouts as a tool for transferring wealth to tenants, even when the tenants leave the city.

- Many housing providers, investors, and brokers see these payouts as a financial burden that complicates sales and increases housing costs.

This is an important point of disagreement and should be addressed by legislators. Legislative records and committee reports from the time TOPA was created suggest that wealth transfer was not the law’s intended goal.71 However, the D.C. Council must ultimately determine what they consider a successful outcome and legislate accordingly.

Lack of meaningful evaluation due to limited data

One of the biggest challenges in assessing TOPA’s effectiveness is the lack of reliable data.

- Weekly public reports on TOPA filings and Tenant Association (TA) formations contain limited and often unclear information, making them difficult to interpret.

- Detailed data are available at the discretion of government agencies or can only be obtained through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. Even then, the information is often incomplete or inconsistent, preventing a comprehensive analysis of outcomes.72

To support informed policymaking, the TOPA data should be collected, reported, cleaned, and made publicly accessible. This data should include:

- TA formations

- TA purchases

- Assignment of rights

- Sales prices and subsidy information

- Outcomes of TA-negotiated deals, including:

- Rent concessions

- Building repairs

- Affordability commitments

- Financial payouts to tenants

Accurate, timely, and detailed data would enable data-driven analyses of TOPA laws, allowing policymakers and stakeholders to make better-informed decisions about the program.

Conclusion

TOPA has evolved significantly since its enactment over 40 years ago, shifting from a tool designed to facilitate tenant ownership into a broader mechanism for negotiating repairs, rent concessions, and financial settlements. While it has contributed to preserving some affordable housing, it has also introduced regulatory complexities that discourage investment in multifamily housing and hinder housing production. The law’s expanded scope, particularly its impact on recapitalizations and investor exit strategies, has created uncertainty that deters both market-rate and affordable housing investment.

The data show that TOPA is primarily used in smaller, older, rent-controlled buildings, with 96 percent of all TA formations occurring in properties built before 1978. This suggests that TOPA is most viable in buildings where tenants have below-market rents, making tenant purchases or affordability protections more feasible. However, the law has discouraged investment in newer, larger buildings that often require large amounts of equity.

Investor interest in D.C.’s multifamily market has declined due to TOPA-related delays, legal uncertainties, and financing risks. By including recapitalizations and transfers of interest in the definition of a sale, TOPA complicates routine financial transactions that are necessary for maintaining and reinvesting in housing stock. The threat of litigation further discourages investment, as any tenant can challenge the process, leading to prolonged legal disputes that stall sales for years. These barriers make D.C. less competitive compared to neighboring jurisdictions with clearer, more predictable real estate regulations.

Perhaps most significantly, there is no clear consensus on what constitutes success under TOPA. Without clear objectives, policymakers cannot effectively measure the law’s impact or determine whether it meets its intended goals. Furthermore, the lack of comprehensive, publicly available data on TOPA transactions prevents meaningful evaluation of its effectiveness.

Moving forward, D.C. lawmakers must clarify TOPA’s purpose, define measurable success metrics, and improve transparency by reporting transaction outcomes. Policymakers should consider targeted reforms that balance tenant protections with investment incentives, ensuring that TOPA serves as a tool for affordability preservation without stifling housing production and rehabilitation. By streamlining processes, expanding data collection, and aligning the law with current housing needs, the District can better support both tenants and the long-term stability of its housing market.

Appendix

Timeline of significant changes to TOPA laws

TOPA laws have changed significantly over time. The following timeline does not include all changes to TOPA, many of which have been determined by the outcomes of court cases, but it does include major legislative changes and large changes to the law’s application.

- 1989 – The original legislation lacked a definition of what quantifies as a sale. This clarification said a sale could include relinquishing possession of the property, a lease with an option to purchase at the end, and transfers of interest.73

- 1994 – A sale was defined as the transfer of 100% of assets to a single person or entity.74

- 1995 – TOPA was amended to allow tenants to assign TOPA rights to a developer or housing provider, permitting the property to remain as rental. The law dictates no rules about how a deal may be structured.75

- 2005 – In response to complaints about sellers evading TOPA through multistep transfers,76 the definition of what constitutes a sale was expanded, making a broader set of transactions subject to TOPA requirements. The definition of a sale was expanded to include transfers of 50 percent of the interest in the property, or a transfer of ownership to another entity of the “principal asset.” This amendment also exempted some transactions from TOPA including foreclosures, bankruptcy sales, transfers from court ordered settlements, and LIHTC investors entering into a project. This amendment also codified the requirement for a Notice of Transfer for smaller transfers of interest where the owner believes it is not subject to TOPA. These notices of transfer allow tenants to challenge whether a minority transfer of interest should require TOPA proceedings.

- 2015 – The Bona Fide Offer Amendments77 require either a third party contract, or an independent appraisal(s) of the property to determine its value.78

- 2018 – Single family units were exempted from TOPA proceedings. The committee report cites the lack of purchases from tenants, and determined that the delays from sales and tenant payouts interfered too much with housing sales and worked against the provision of affordable housing as it discouraged rentals in the District.79

Other modifications include adjustments to timelines and additional supports from the D.C. government for tenant associations.

Appendix tables

Appendix graphs

About the data

Data on rental housing units was compiled using data from CAMA ARU Derived Counts and excluding all owner-occupied housing (estimated using the homestead exemption code). The D.C. Policy Center also compiled a database to determine rents and market segmentation using a combination of public tax extracts, data on affordable housing units (available at opendata.gov) and CoStar. This database was constructed in October, 2024 and reflects the data available at that time.

Data on sales and TA formation for this paper was collected by Greysteel, a middle market real estate firm for private and institutional investors. Sales data was collected from January 2012 to February 2023 from CoStar, and matched with data on tenant association formation that was acquired from DHCD weekly filings (dating back to August 2016) and internal records (dating back to 2014). Duplicate records were removed, as were condominium sales, and transfers of interest that did not trigger TOPA. Greysteel employees then conducted interviews to determine the outcomes of each transaction. The data included in this paper represents 16,890 units in 425 sales. Of these sales, there were 158 instances in which a tenant association formed, representing 7,409 units.

The D.C. Policy Center conducted interviews on experience with TOPA with 13 stakeholders in the housing sector including non-profit developers, market rate developers, title agents, tenant attorneys, landlord attorneys, institutional investors, and brokers. These interviews informed the information contained in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This report has been prepared by The Wilkes Initiative on Housing Policy. It has been, in part, supported by The Developer Roundtable. The authors thank the Roundtable for their comments and suggestions, and for the facilitation of meetings and interviews with various stakeholders including housing providers, investors, title agents, and attorneys. Additionally, the authors thank all interviewees that participated in this project and Graysteel for the initial connection of TOPA weekly reports with CoStar data.

The report has benefited from thoughtful review and recommendations from Tom Borger, Patrick McAnaney, David Roodberg, and Forrest Albiston and Roger Winston of Ballard Spahr. Their review does not endorse this report, and all errors are the responsibility of the D.C. Policy Center authors.

Endnotes

- Very few rental apartment buildings were constructed between 1978 and 2007, as housing production declined sharply in 1978, just before TOPA was enacted. Only 5 percent of D.C.’s current rental stock was built between 1978 and 2007, and of a third of these were owned by the D.C. Government or otherwise tax exempt.

- We define affordable as buildings with at least half the units affordable at or below 80 percent of Median Family Income.

- While this timeline was frequently mentioned by investors, investor timelines may vary significantly due to many factors including market conditions, affordability covenants, and details of the sale.

- Under existing regulations, any transfer of interests which “in effect results in the transfer of the housing accommodation” is considered a sale, even if the original developer and property management remain unchanged. In effect, this means any transfer of more than 50 percent of the interest. Transfers of less than 50 percent interest can also potentially trigger TOPA if the Notice of Transfer is challenged.

- This also occurs when tenants are issued a notice to vacate for purposes of demolition or discontinuance of housing use.

- Rental Housing Conversion and Sale Act of 1980 D.C. Code §42-3401.02.

- Rental Housing Conversion and Sale Act of 1980 D.C. Code §42-3401.02.

- Gallaher, C. (2006). The Politics of Staying Put. Temple University Press.

- Cited in the original legislation.

- The numbers reported in the book are 1,147 rental apartment buildings with 26,645. Gallaher, C. (2006). The Politics of Staying Put: Condo Conversion and Tenant Right-to-Buy in Washington DC. 2016.

- This environment is documented in the Official D.C. Code and were based on the research and findings by two legislative study commissions: The D.C. Legislative Commission on Housing and the Emergency Commission on Condominium and Cooperative Conversion. https://code.dccouncil.gov/us/dc/council/code/titles/42/chapters/34

- This change was intended to make sure buyers and sellers cannot avoid TOPA when the intent was to transfer 100 percent of the interest, but the deal was structured with multiple transactions at lower than 100 percent of the interest.

- Burge, D. (April 8, 2024). Business Sentiments Survey 2024 Quarter 1 results. D.C. Policy Center. https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/business-sentiments-survey-2024-quarter-1-results/; Burge, D. (January 15, 2025). Five findings from the inaugural year of the D.C. Policy Center’s Business Sentiments Survey. D.C. Policy Center. https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/five-findings-from-inaugural-year-business-sentiments-survey/

- Committee on Housing and Neighborhood Revitalization Committee Report. (February 23, 2018). Council of the District of Columbia. https://lims.dccouncil.gov/downloads/LIMS/38263/Committee_Report/B22-0315-CommitteeReport1.pdf?Id=62198

- (1) To discourage the displacement of tenants through conversion or sale of rental property, and to strengthen the bargaining position of tenants toward that end without unduly interfering with the rights of property owners to the due process of law; (2) To preserve rental housing which can be afforded by lower income tenants in the District; (3) To prevent lower income elderly and disabled tenants from being involuntarily displaced when their rental housing is converted; (4) To provide incentives to owners, who convert their rental housing, to enable low-income tenants to continue living in their current units at costs they can afford; (5) To provide relocation housing assistance for lower income tenants who are displaced by conversions; (6) To encourage the formation of tenant organizations; (6a) To balance and, to the maximum extent possible, meet the sometimes conflicting goals of creating homeownership for lower income tenants, preserving affordable rental housing, and minimizing displacement; and (7) To authorize necessary actions consistent with the findings and purposes of this chapter. D.C. Code Ann. 42-3401.02

- Committee on Housing and Neighborhood Revitalization Committee Report. (February 23, 2018). Council of the District of Columbia. https://lims.dccouncil.gov/downloads/LIMS/38263/Committee_Report/B22-0315-CommitteeReport1.pdf?Id=62198 p 5

- Act Number: A21-0072 | Law Number: L21-0019

- Act Number: A22-0376 | Law Number: L22-0149

- Act Number: A25-0302 | Law Number: L25-0102

- Act Number: A21-0191 | D.C. Law 20-229; 62 DCR 276

- B25-0608 – Paul Laurence Dunbar Apartments TOPA Exemption Temporary Act of 2023. https://lims.dccouncil.gov/Legislation/B25-0608

- B25-0558 – Jeremiah House and Shalom House TOPA Exemption Act of 2023. https://lims.dccouncil.gov/Legislation/B25-0558

- Washington DC’s Housing in Downtown Program: Program Explainer Deck FY 24. (January 2024). Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development. https://dmped.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dmped/page_content/attachments/Housing%20in%20Downtown_DMPED%20January%202024.pdf#:~:text=The%20HID%20program%20would%20relax%20TOPA%20through,time%2Dlimited%20exemption%20for%20HID%20approved%20projects%20only.

- Sustaining Affordability: The role of the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) in Washington, D.C. (2023). Coalition for Nonprofit Housing and Economic Development. https://cnhed.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/CNHED_TOPAStudyNov09.pdf

- Ibid

- Ibid page 60

- Some TOPA exemptions include adding a new partner for capital contributions in exchange for LIHTC tax benefits (specifically does not include transfer to a new owner for LIHTC), transfers to immediate family members and transfers from estate of surviving family member, transfers from loan foreclosures and establishing deed of trust, tax sales and tax foreclosure sales, bankruptcy sale, change in form of entity as long as no consideration is exchanged, transfers from court order or court approved settlement, and transfers from eminent domain. D.C. Code § 42–3404.02.

- In cases where there is not a sales contract in place, the tenants must be given a “bona fide offer” meanings a sales price that is less than or equal to the appraised value or fair market value. Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Bona Fide Offer of Sale Clarification Act of 2015https://code.dccouncil.gov/us/dc/council/laws/21-26

- Lawsuits over the years have shown that the definition of tenant is not well defined. There are reports of tenants who had previously left buildings joining tenant associations and getting buyouts. Lawsuit in which previous tenant assigned TOPA rights and court recognized it. Lawsuit involving a previous tenant who assigned his TOPA rights despite having waived them in a previous settlement: Papageorge v Stuckey, 196 A3rd 426 (D.C.2018). Other examples of possible tenants: someone who has stayed in the unit temporarily but is not on the lease, reports of having to contact past tenants going back years. This is a bigger issue in buildings where there is a small number of units, such as 2 to 4 unit buildings. In 5 unit or more buildings, it is easier to ensure that the tenant association encompasses the majority of the tenants.

- O’Toole, A. W., & Jones, B. (2009). Tenant Purchase Laws as a Tool for Affordable Housing Preservation: The D.C. Experience. Journal of Affordable Housing & Community Development Law, 18(4), 367–388. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25782856

- This timeline can be extended if information requested by tenants is not provided in the allotted timeframe, if the owner enters into a third party contract within the negotiation period, or if a third party is offered a contract that is more than 10% less than the price offered to tenants. D.C. Code § 42–3404.02.

- While technically a registered TA is the only party with TOPA rights, challenges can arise. First, there have been cases in which there is more than one registered TA, and as there is no current method to certify which TA has legal standing. Second, any tenant can claim non-compliance with TOPA, which has led to situations where a single tenant or a small group threatens legal action even after the TA has negotiated and reached an agreement with the purchaser.