Last week was truly difficult. The potential loss of the Capitals and the Wizards to Virginia’s suburbs is a disquieting turn of events for the District’s already struggling Downtown. This news, as wounding as it is, shines a bright light on how the policy discourse in the District of Columbia must reset and refocus on the fundamentals of success: economic growth, competitiveness, and opportunity. The teams will still be playing in the Capital One Arena for at least the next four years. This gives the city time enough to reimagine and reengineer Downtown. But it will require the hard work of coordinated action and disciplined prioritization.

Why is the Arena (and the teams) such a big deal?

A lot of us were upset when we heard that the teams we love could move away. But the economic loss associated with such a departure is much greater than the loss of the teams and their games. It was the Arena that revitalized the Chinatown neighborhood and contributed to the general improvement of the city’s economy when it opened in 1997. It changed the trajectory of not just Chinatown, but neighborhoods nearby as well, catalyzing the development of residential and office buildings, and the creation of a strong local service economy.

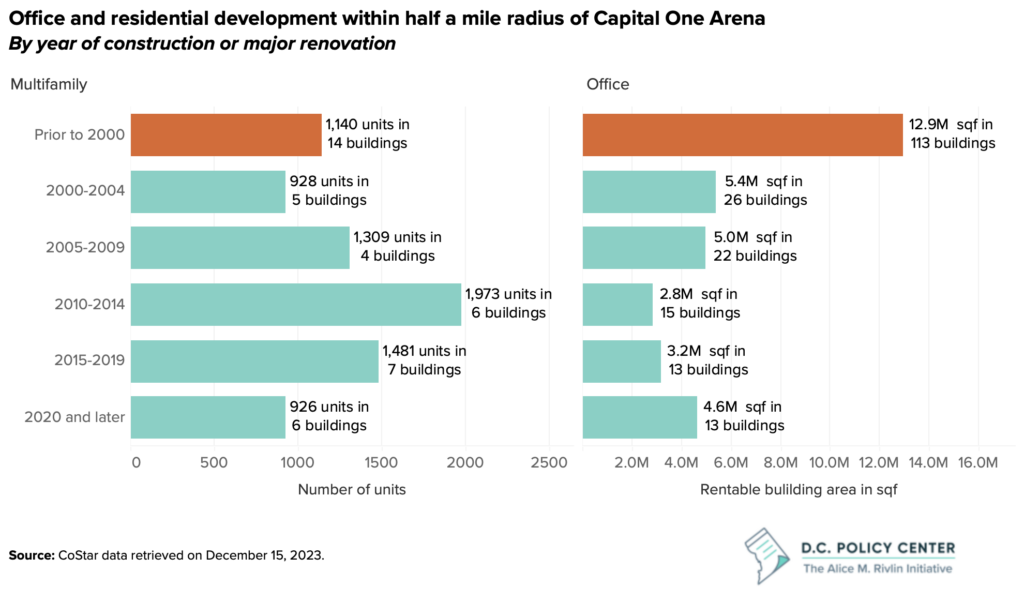

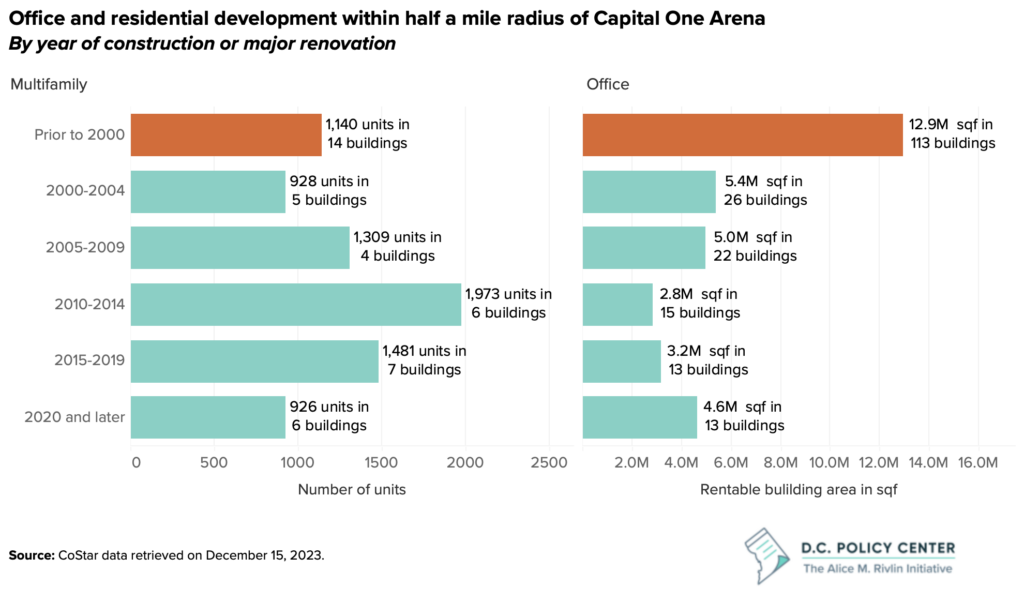

When the Arena opened in 1997, there were 14 residential buildings with 1,140 units within half a mile radius of its location. Since then, the city added 28 new residential buildings with 6,616 units in the same geographic area. This is an increase of an order of magnitude, not just in the number of households that can live within half a mile of the Arena, but also in the income and sales taxes collected from these households and property taxes collected from the buildings in which they live.

Similarly, at the time the Arena opened, there were 113 office buildings within half a mile radius with 13 million square feet of office space. Since then, the city added 94 more office buildings with 23 million square feet of space in the same radius. Again, this is a difference of an order of magnitude, and it has provided significant tax revenue that was invested in government services and supports.

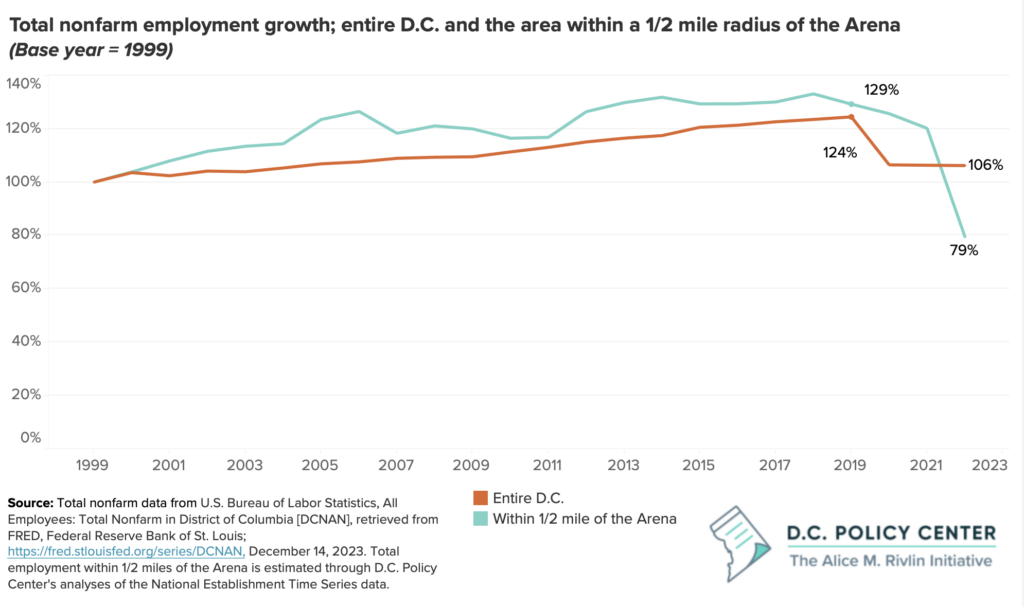

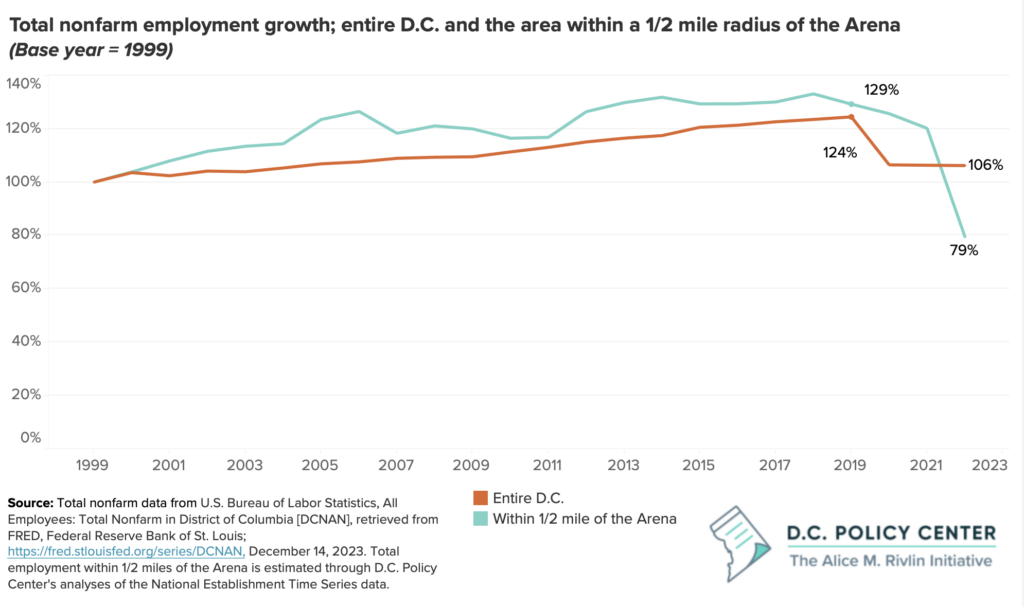

Importantly, this rapid development resulted in employment growth that was faster than the rest of the city up until the COVID-19 pandemic. Between 1999 and 2019, the area within a half a mile radius of the Arena added an estimated 48,250 jobs—an increase of 29.2 percent compared to the 1999 level.1 During the same period, non-farm employment across the entire city increased by 24.4 percent.2

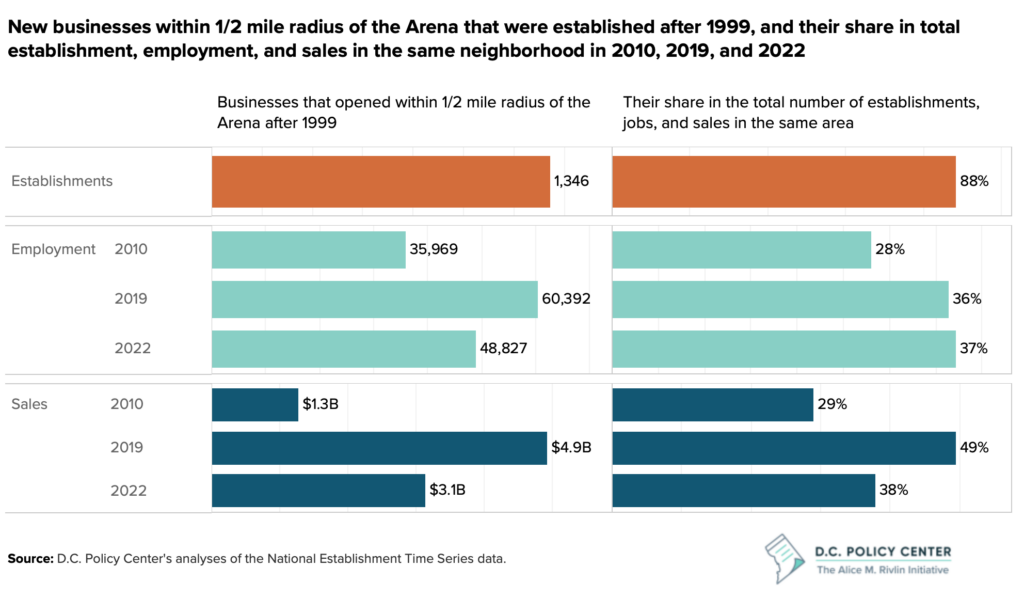

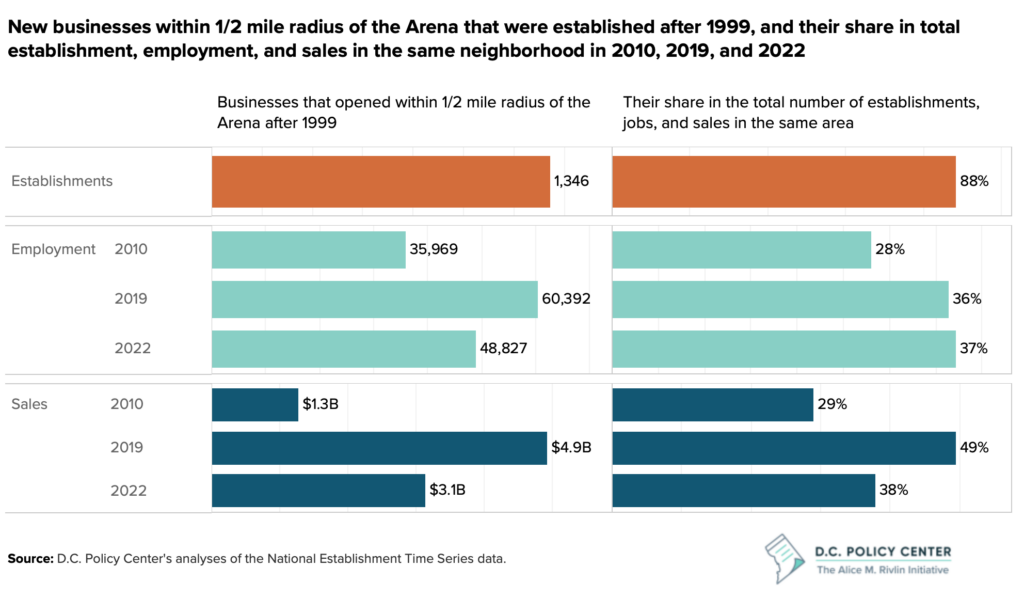

A lot of the economic activity and growth around the Arena have been propelled by new businesses. Since 2000, 1,346 new businesses started up within half a mile of the Arena. These businesses account for 88 percent of all business establishments that opened and operated in the same area since 1980 (the same share for entire D.C. is 60 percent).3

By 2010, these new businesses were accounting for 28 percent of all employment and 29 percent of all sales within half a mile of the Arena. And, by 2019, they were hiring 36 percent of all workers within that area and generating nearly half the sales. Unfortunately, many of these businesses did not survive the COVID-19 pandemic and its damaging impacts. By 2022, only 864 out of the 1,346 new businesses that were established after 1999 were still active, and the area had lost 12,000 employees and nearly $1.8 billion in annual sales.

These numbers underscore the transformational changes that happened in Chinatown and nearby neighborhoods between 2000 and 2019. The growth in business activity created jobs and economic opportunity and contributed substantially to public resources that pay for important government investments. The presence of the Arena especially contributed to the creation of smaller businesses such as restaurants and retail stores in Chinatown and nearby neighborhoods. These establishments created jobs for workers without sufficient credentials to work in the highly competitive fields of professional, technical, and business services, finance, information, or the public sector. In 1999, for example, there were 69 restaurants within half a mile of the Arena. Since then, 139 more opened (some replacing existing ones). Unfortunately, today only 98 restaurants remain. Should the Arena significantly reduce the number of events held there, many of these could also close or move elsewhere, resulting in the potential loss of up to 2,250 jobs and $76 million in annual sales.

What are some of the opportunities for the redevelopment of Downtown?

While the potential loss of the teams would be significant, it need not define the future of Downtown or the city. The District has important advantages over other cities and jurisdictions, which, if used well, can help chart a stronger course for the future.

A unified government

The first advantage that the District of Columbia has is that it is a single level of government that has both local level responsibilities such a schools, firefighters, and police (though public safety functions are shared with the federal government) and state level responsibilities such as public transportation, public health, and human services. These functions are fragmented across multiple levels of governments in other states and cities. Similarly, D.C. has sole control of its tax regime, with taxing powers that are usually split between state and local governments in all other jurisdictions.

District’s unified government can be a tremendous source of strength and competitiveness for the city: it can open doors to holistic policies that can recognize interdependencies—such as those between housing, education, transportation, and economic development—and can do so without the jurisdictional tensions observed between state and local governments elsewhere. It can also help the city deploy stronger economic development tools that can, for example, mix tax incentives with government supports, so long as the city can execute them with stronger coordination between the executive and the legislative branches.

Unique access to publicly owned assets

The second advantage the city has is its access to a unique set of assets. The District’s downtown is home to a number of publicly-owned assets that can be redeveloped in collaboration with the federal government and the private sector. The District has successfully leveraged public assets before, at the Yards (originally a federally-owned property flanked with industrial neighborhoods, and financed by a PILOT), the Wharf (another federal land disposition financed by a combination of a TIF and a PILOT), the City Center (the old Convention Center), just to point out a few examples.

One important asset the city could redevelop in collaboration with the federal government and the private sector is the Edgar J. Hoover Building—the FBI headquarters—which comprises an entire city block at the heart of Downtown. At present, this is a low-rise office building, with singular security features that are designed to repel, and not attract, people. This 5-acre land is large enough to redevelop with a mix of uses with a clear connection to the Chinatown/Gallery Place area. Redeveloping this property will require federal buy-in, but its value proposition for both the District and the federal government can lay the ground for common cause. Another example is Union Station, which can unlock tremendous economic development opportunities, but it too will require federal support and collaboration.

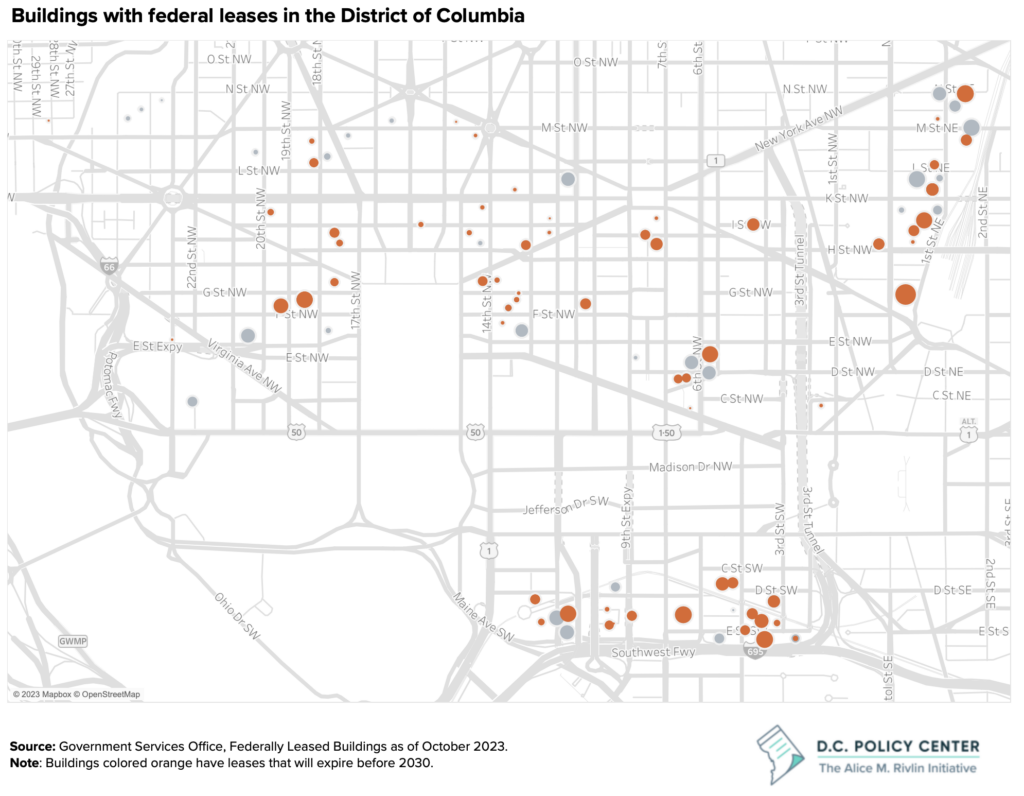

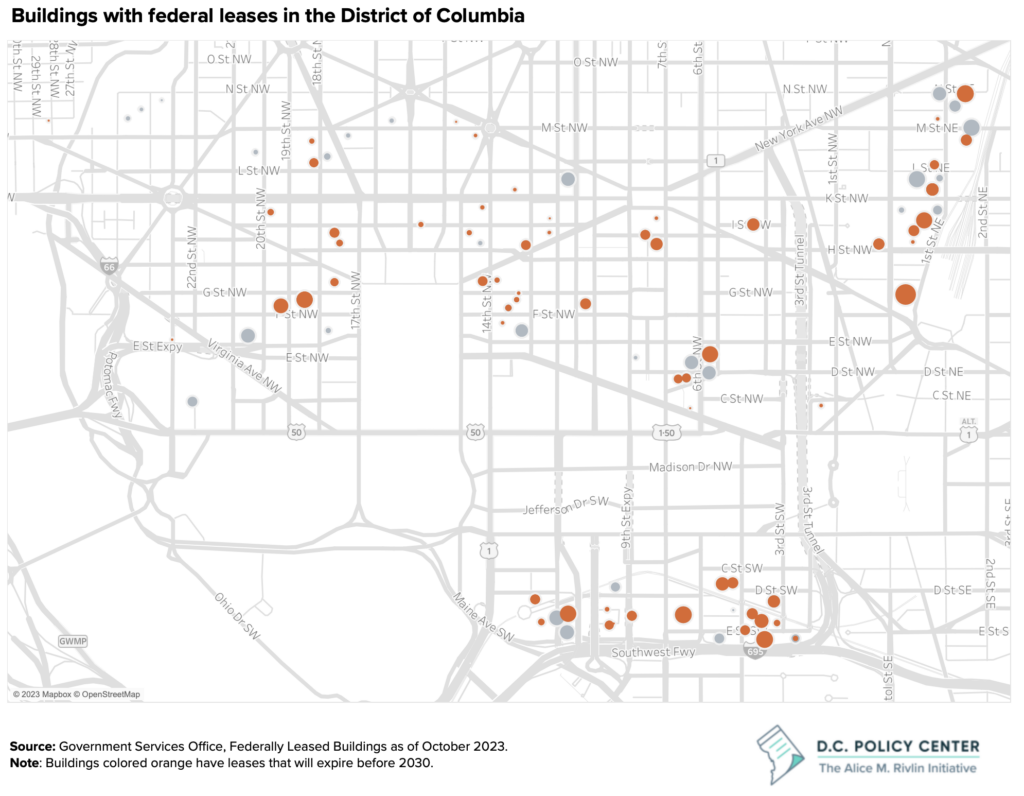

There are other opportunities to collaborate with the federal government as well. At present, the federal government leases 175 buildings in D.C., which collectively account for 32 million square feet of office space. These buildings are generally underutilized. A recent analysis from the General Accountability Office found that office occupancy in federally owned and operated buildings remains under 25 percent. Hence, as GSA leases expire, it is unlikely that the federal government will hold on to many of these properties. Data from GSA show that leases will expire in 114 of these 175 buildings before 2030 (accounting for about 20 million square feet). If current occupancy trends continue, many of these leases will likely not be renewed, putting additional pressure on the District’s already weak office market. The District could work with the federal government and building owners to redevelop these buildings in return for earlier lease terminations.

Access to privately owned assets that need repurposing

Another set of assets that can be a part of Downtown’s transformation is large commercial office buildings that are no longer financially viable, and therefore could be purchased at less than replacement cost. Current conditions in Downtown have compressed office values in unprecedented ways. Recently, four large office buildings have turned the keys over to their lenders, and many are likely to follow suit. 4

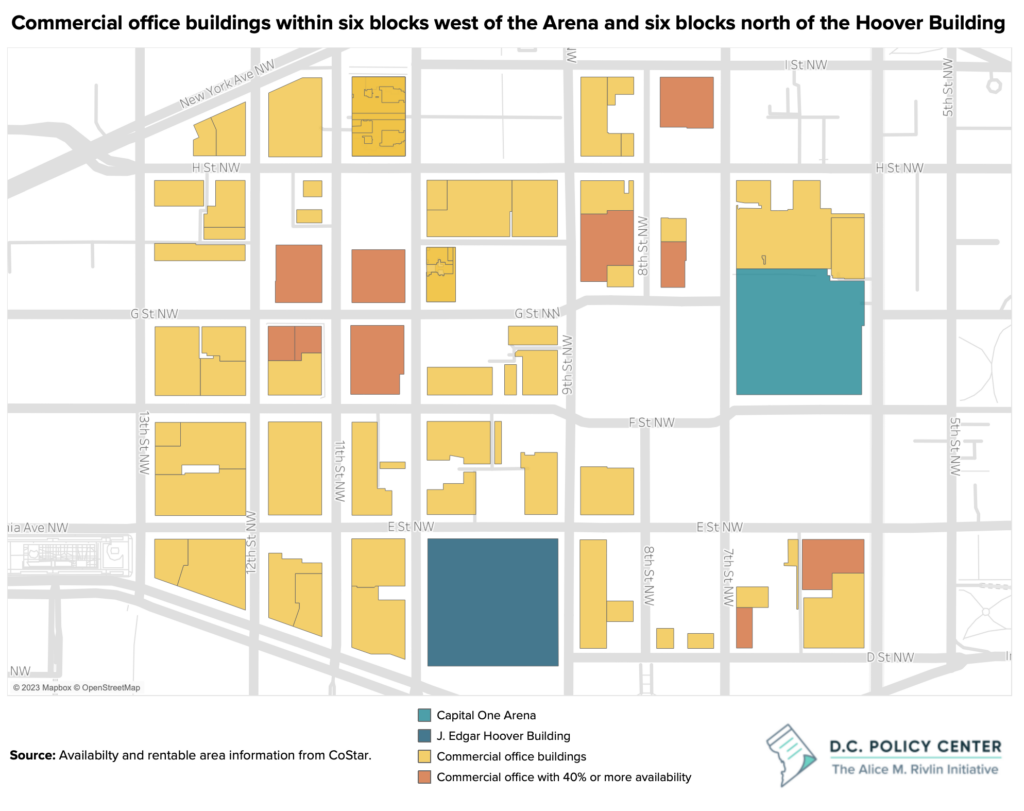

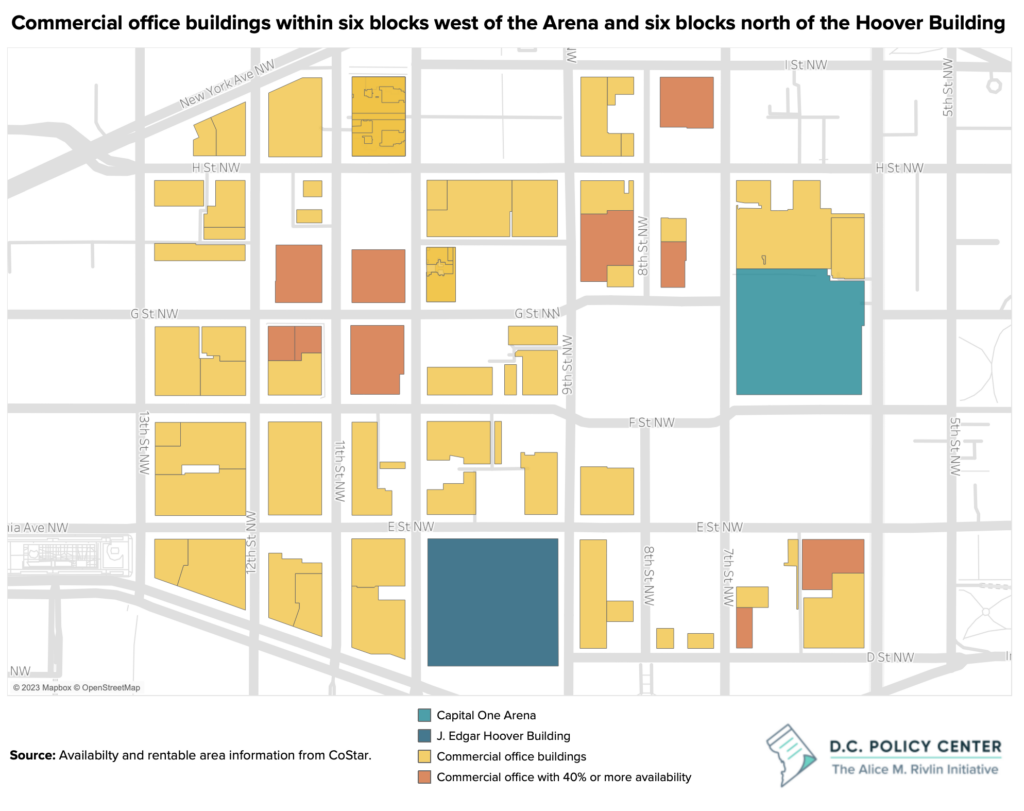

Typically, lenders are not interested in owning buildings. This can create an opportunity for the District to negotiate a coordinated acquisition of these buildings, especially if they in are close proximity of each other. An examination of large commercial office buildings within six blocks west of the Arena, and six blocks north of the Hoover Building shows at least 13 buildings with availability (the amount of rentable space that is either vacant or soon will become vacant) over 40 percent of their total rentable spaces. This, again, provides an opportunity to plan and redevelop an entire block or subarea, which is much more powerful than redeveloping a single building for alternative use.

What next?

A lot of work needs to be done, and done quickly, to chart a recovery course for the District. Some of this important work has already been done through the District’s Comeback Plan, now being further developed by the reimagining work led by the Downtown BID, the Golden Triangle BID, and the Federal City Council. But there is still much to do.

A crucial next step for the city is to determine the vehicle through which the revitalization efforts can be undertaken. One potential vehicle is a limited-duration partnership between the District government, the federal government, and the private sector, which can bring together vision, coordination, assets, and funding for a Downtown Redevelopment Zone. This partnership can be empowered by temporary ownership of assets and authority over redevelopment decisions, with specific targets to be met by specific dates. It could be seeded with the $500 million in capital funding the city identified this week for economic development. This would be a tremendous beginning, with funds to invest in acquisition, construction, infrastructure, and even public safety measures and open space.

The District government must also think through the regulatory environment and what impediments exist on the path to rapid redevelopment. These include delays associated with zoning requirements, site plan approvals, or permitting, which bring costly delays. Solving those problems in the context of Downtown redevelopment will make a more efficient government city-wide and for everyone.

Further, the city will also have to make some hard, and potentially unpopular, decisions. For example, affordability requirements in residential development carry a high social value but can also carry a high cost. Can the District rethink these requirements for the Downtown Redevelopment Zone and assess the tradeoffs between the social value of affordable housing and, for example, the need for workforce housing?

Similarly, First Source requirements can create unduly burdens without necessarily creating jobs for District residents. Recent D.C. Policy Center research found that only 9 percent of the 15,200 construction workers who work in D.C. live in D.C. This makes it extremely difficult to meet First Source requirements for construction projects. The District can use Downtown redevelopment to test alternative workforce plans that allow developers to invest in workforce training and receive credit towards their First Source requirements.

These ideas will not be popular with everyone. And certainly, they are not the only ways to redevelop Downtown. But whatever path the city takes, it will have to draw strength from its unified government, its access to unique assets, and partnership with the federal government and the private sector while prioritizing economic growth and creating a regulatory environment that bolsters the city’s ability to attract investment.

Data sources and notes

- Residential and office development within half a mile radius of the Capital One Arena is estimated by using data from CoStar.

- Business establishments, employment, and sales activity within half a mile radius of the Arena is estimated by using the National Establishment Time Series Database. This analysis excludes business establishments with fewer than 5 employees. For more details on why we made this decision, see hereand here.

- Total non-farm employment data for D.C. is obtained from FRED.

- Federal government lease data is obtained from the General Services Administration.

- The location of commercial office buildings with availability that exceeds 40 percent of the rentable space is developed by using data from CoStar, the city’s tax rolls maintained by the Chief Financial Officer, and Common Ownership Lots spatial files.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Nicholas Dodds for his invaluable help and assistance with the NETS Database analyses.

Endnotes

- D.C. Policy Center analyses of the NETS data. This estimate excludes employment at establishments with fewer than five employees.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, All Employees: Total Nonfarm in District of Columbia [DCNAN], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DCNAN, December 14, 2023

- D.C. Policy Center analyses of the NETS data.

- As vacancy rate increases, it becomes increasingly difficult for landlords to meet their operating expenses. And if leasing activity does not improve, such buildings will experience significant asset devaluation. And if they are highly leveraged, they will most likely be returned to the lender.