Understanding the District of Columbia’s criminal justice system is imperative as D.C. works toward racial equity, statehood, and criminal justice reform. D.C.’s criminal justice system is administered mainly by the federal government—a direct result of the Revitalization Act. This makes D.C.’s system uniquely complicated, with far-reaching impacts on D.C. residents.

A long list of entities and agencies make up the District’s criminal justice system. Which ones are local, and which are federal? What are their individual responsibilities, and how are they funded? Finally, how does an individual D.C. Code offender process through this complicated stream of entities?

About this series

This publication is part of the D.C. Policy Center’s Criminal Justice Week 2023, which explores various aspects of the District’s criminal justice system. Other publications in this series include:

- How D.C.’s criminal justice system has been shaped by the Revitalization Act

- A look at who is in D.C.’s criminal justice system

- How much would it cost to build and maintain a new D.C. prison?

- Map of the week: Where are D.C. Code offenders housed today?

These publications are adapted from The District of Columbia’s Criminal Justice System under the Revitalization Act: How the system works, how it has changed, and how the changes impact the District of Columbia, commissioned by the District’s Criminal Justice Coordinating Council.

In most state criminal justice systems, state-level agencies (such as the courts and the state prison systems) and local-level agencies (such as the police departments) share responsibilities, with little federal intervention or control. Due in large part to the Revitalization Act, the District’s criminal justice system looks very different from that of a typical state.

D.C. Code offenders bounce between local and federal agencies

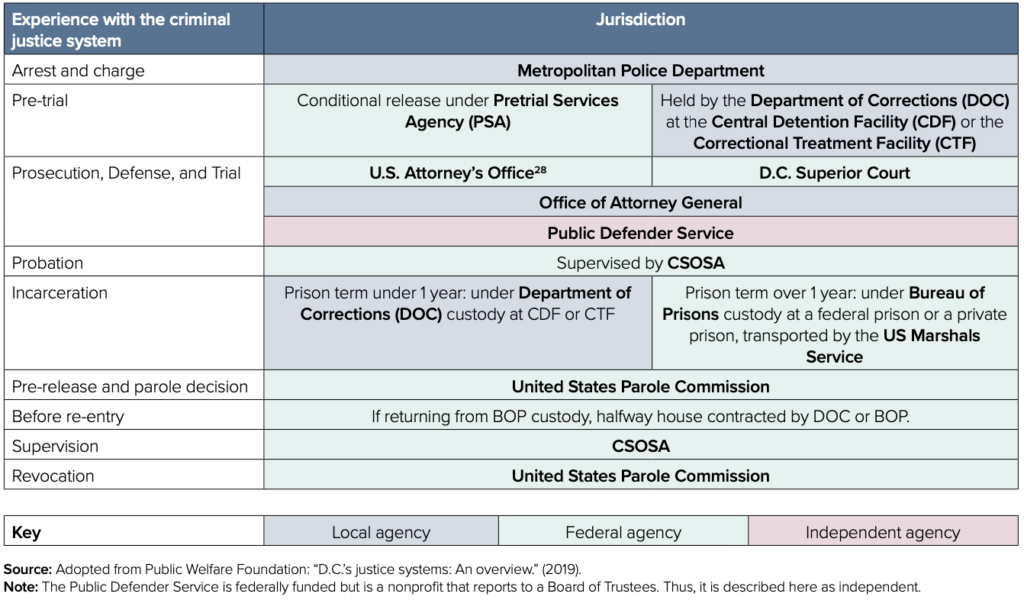

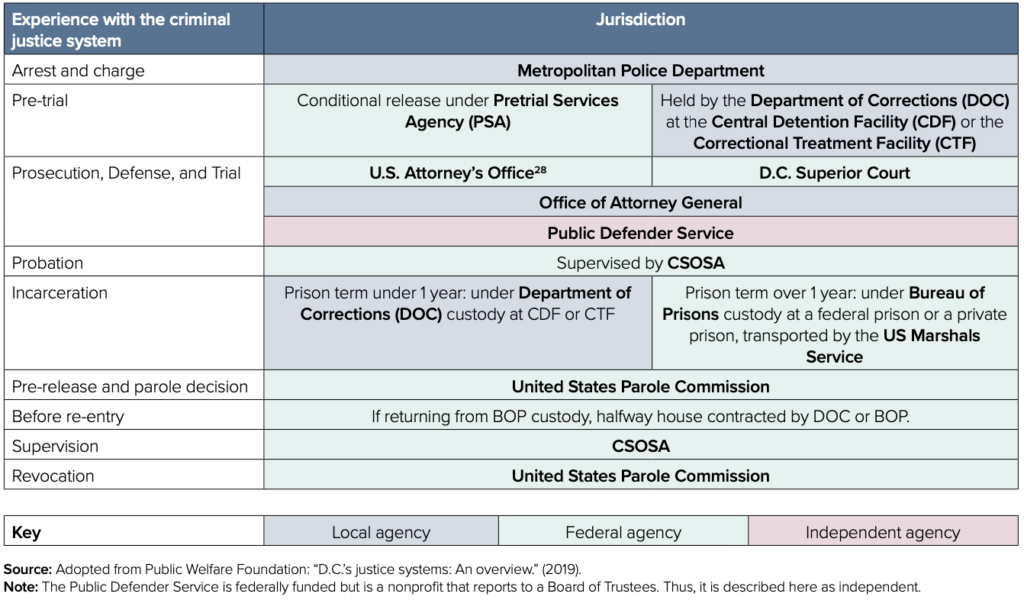

In the District, experience with the criminal justice system typically starts with (the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD)1—a local agency—but from that point on, D.C. Code offenders find themselves bouncing between local and federal agencies (Table 1).2 As such, people convicted of crimes in D.C. follow a chain of custody and supervision that is split between local and federal agencies.3

Table 1. Criminal justice agencies and jurisdiction

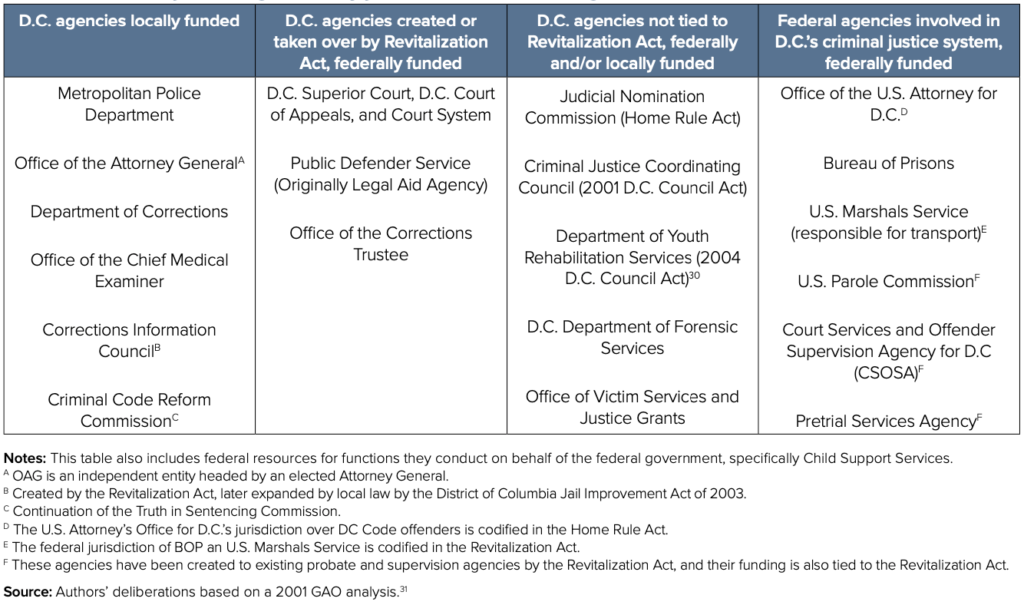

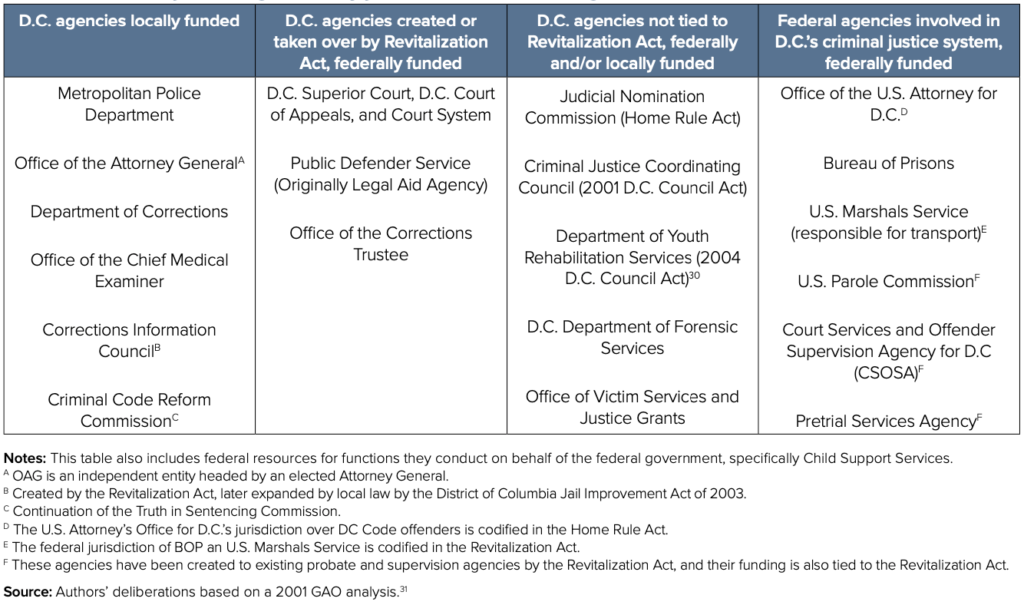

Funding sources: A mix of federal and local

In addition to jurisdiction being split between local and federal agencies, funding for the District’s criminal justice system is from a mix of local and federal government resources. Some of these expenditures are explicitly appropriated for D.C. agencies in the federal budget. These include the courts, defender services, pretrial and supervision services, coordination services, and contributions towards the judges’ retirement system.

Other funding is absorbed within federal agency budgets without specific allocations to D.C. These include the incarceration of D.C. Code offenders in BOP facilities, including transportation of incarcerated persons, and USPC hearings regarding parole or supervised release.

Most—but not all—of the federal funding is tied to provisions of the Revitalization Act, or, in some cases, the Home Rule Charter (Table 2). All agencies under Mayoral control are funded locally. These primarily include the Metropolitan Police Department and the Department of Corrections, which runs the city jail.

Table 2. Criminal Justice agencies by jurisdiction and funding source

Prosecution: Office of the U.S. Attorney for D.C.

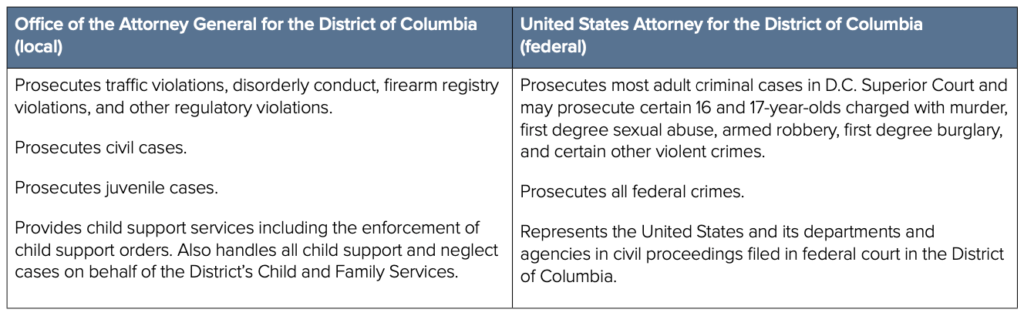

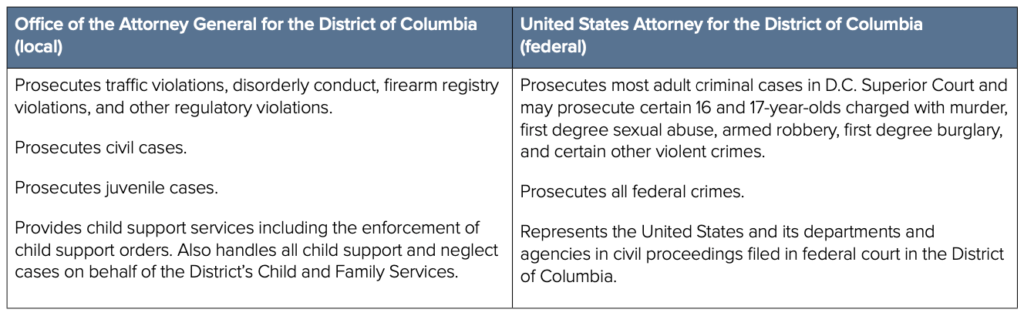

The authority to prosecute cases for D.C. Code offenders has never been under local jurisdiction. By statute—and codified in the Home Rule Charter—in the District of Columbia, the U.S. Attorney, which is a part of the federal Department of Justice, serves as both the federal prosecutor (similar to the other 92 U.S. Attorneys’ offices across the country) and as the local district attorney. This means the job of prosecuting cases for D.C. Code offenders in D.C. Superior Court falls on the U.S. Attorney’s Office for D.C. and not the District’s own Attorney General, as is the case in all other states. The U.S. Attorney prosecutes most adult criminal cases in the Superior Court. In cases involving juveniles, traffic violations, or certain low-level “quality of life” misdemeanors, the Office of the Attorney General of the District of Columbia is the prosecutor.4 5

Table 3. Prosecution duties of the D.C. Office of the Attorney General and the U.S. Attorney for D.C.

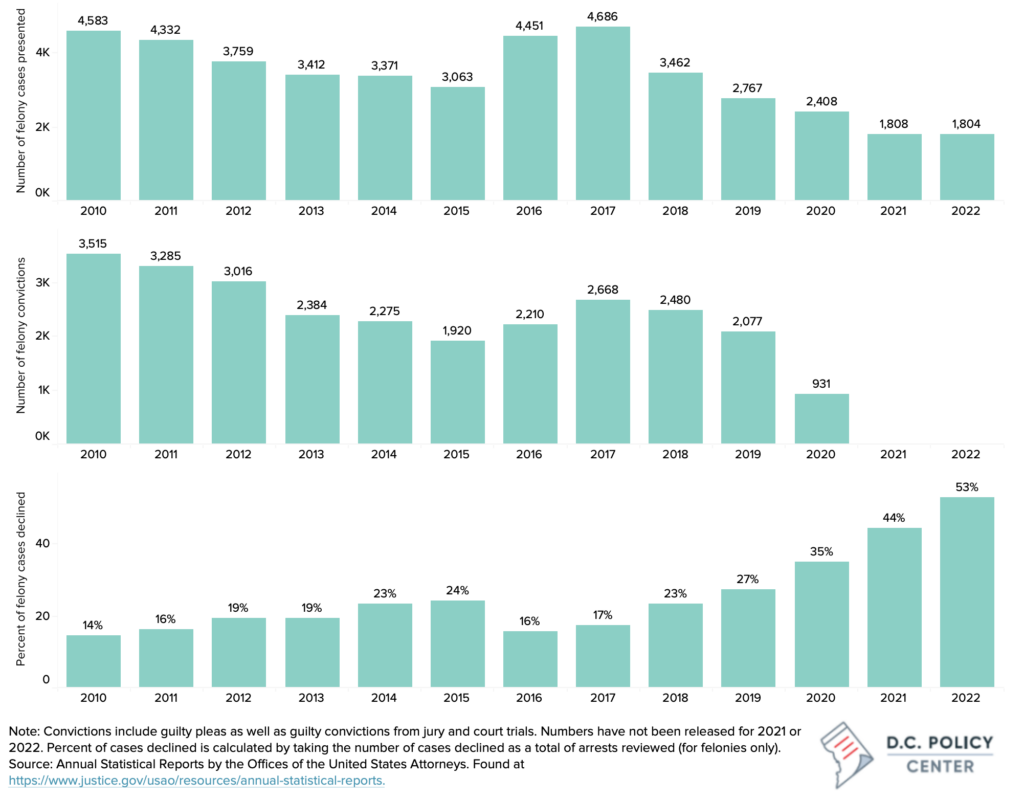

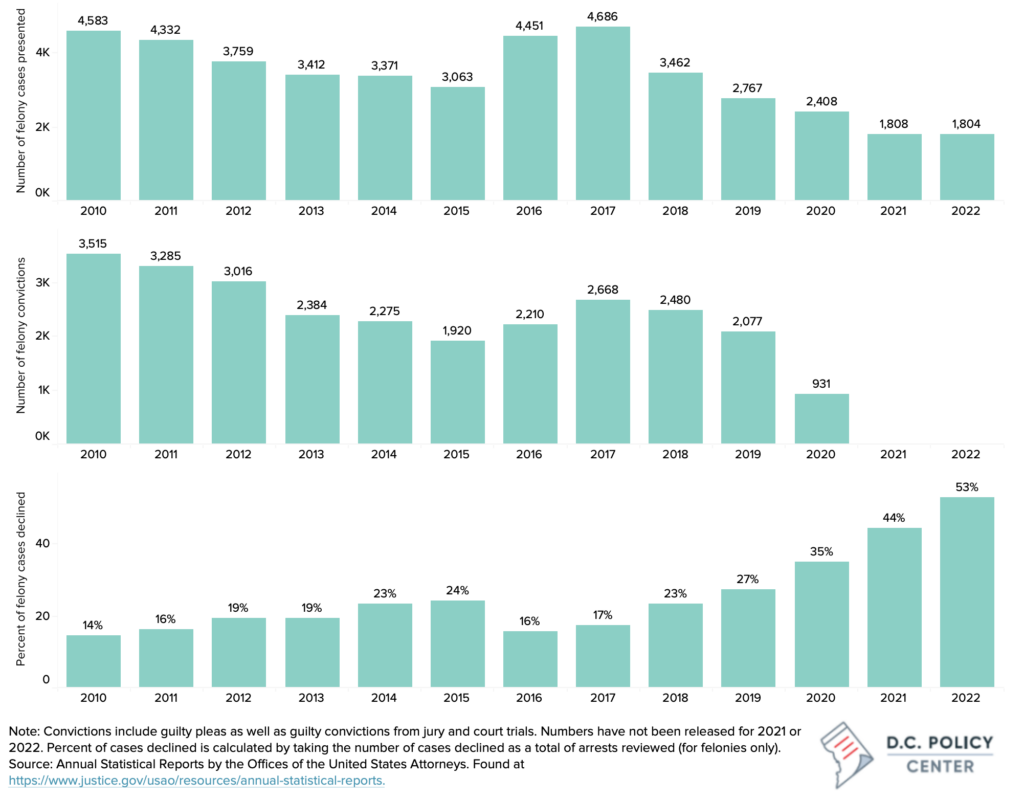

The U.S. Attorney for D.C. has 330 Assistant United States Attorneys and over 350 support personnel distributed over five different divisions, including the division that serves as the local district attorney for D.C.6 According to data retrieved from the Department of Justice, the U.S. Attorney’s Office prosecutes approximately 400 cases at the D.C. Superior Court each year, although this number has varied greatly over time (Figure 1). In recent years, more than 80 percent of the cases closed have resulted in a sentence.

Figure 1. Criminal prosecution by USAO in the District of Columbia Superior Court, 2010 to 2022

The federal funding of prosecution has likely been a significant fiscal benefit to the District. The U.S. Attorney’s Office estimated that, in fiscal year 2021, the amount spent on local prosecution was $55 million.7 In comparison, the D.C.’s Attorney General’s Office’s budget for the same year was $134.5 million, of which $106.9 million were District’s own funds8 and $23.6 million were federal funds.9

Defense: Public Defender Service

Independent from the rest of the criminal justice system is the Public Defender Service, which provides defense counsel for people who cannot afford an attorney, including D.C. Code offenders. The origin of the Public Defender Service dates to the 1960s, but it was transformed into a federally funded independent entity (a non-profit organization that reports to a Board of Trustees) by the Revitalization Act.

The Public Defender Service (PDS) is highly regarded for its representation of individuals charged with the most serious adult felony cases and criminal appeals. PDS also represents nearly all individuals facing parole revocation under the District of Columbia Code, all defendants at Drug Court sanction hearings, and individuals facing involuntary civil commitment in the mental health system.10 Additionally, the Public Defender Service also works on legal issues and barriers related to successful community reentry and provides technical assistance and training for Criminal Justice Act (CJA) and pro-bono attorneys.11

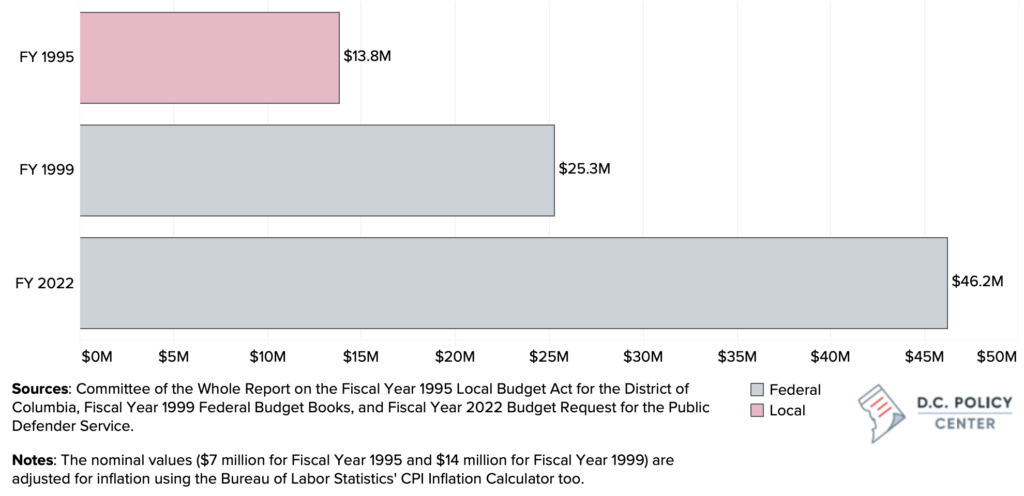

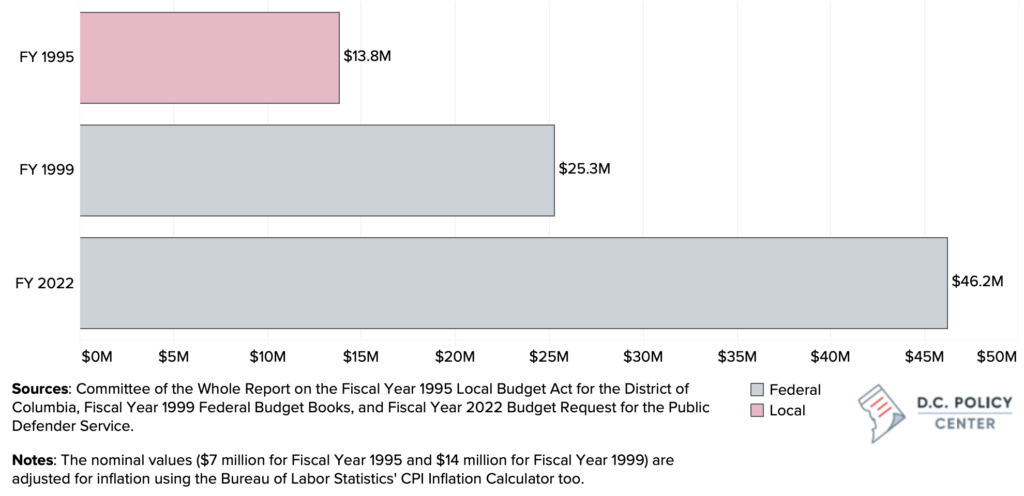

Federal funding from the Revitalization Act was likely a significant help to the Public Defender Service, particularly at the time it was enacted (Figure 2). Before the implementation of the Revitalization Act, the District of Columbia typically budgeted $7 million for this entity, which is the equivalent of $13.4 million in 2022 prices. Officials who were working at the Public Defender Service at the time of the Revitalization Act said that the organization was facing major budget cuts that might have resulted in the reduction of as much as half the staff at the time.12 The first year after the implementation of the Revitalization Act (1999), the federal government appropriated $14 million for the Public Defender Service, which is the equivalent of $25.3 million in today’s prices. In Fiscal Year 2022, the budget for the Public Defender Service was $46.2 million supporting 222 full-time equivalent positions.13 According to officials who previously worked at PDS, better pay tied to increased resources, eligibility for federal benefits, and organizational commitment to a more reasonable workload have potentially made jobs more attractive than they had previously been.14

Figure 2. Funding for the Public Defender Service before and after the implementation of the Revitalization Act (expressed in 2022 dollars)

Pretrial Supervision: Pretrial Services Agency

The District’s Pretrial Services Agency (PSA) was created by an act of Congress (the District of Columbia Bail Agency Act) in 1967.15 Under the Revitalization Act, PSA was established as an independent entity within the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA) in the Executive Branch of the Federal Government.16 The main function of this agency was largely unchanged by the Revitalization Act, as PSA always provided services to both federal and D.C. Code offenders.17

PSA submits release recommendations to D.C. courts on people arrested in D.C. and provides supervision and coordinated treatment services for released persons. These include assessments of treatment needs; a Drug Court program for defendants charged with misdemeanors or non-violent felonies, and a Specialized Supervision Unit specifically focused on defendants with mental health treatment needs. According to its Fiscal Year 2022 budget request documents, in 2021 the PSA supervised over 15,450 defendants on pretrial release, in addition to providing services such as court date notification and criminal history checks for persons who were released on citation or personal recognizance, or whose charges were dismissed for 12,789 defendants. Combined, PSA served more than 28,240 defendants during this period in addition to conducting drug testing for 8,874 non-defendants.18

PSA’s current caseloads include individuals being supervised on a full range of charges from misdemeanor property offenses to felony murder, and most defendants (97 percent) are awaiting trial in D.C. Superior Court. As such, almost all the funding PSA receives from the federal government supports their D.C. work.

Pretrial services likely benefited from increased resources when the funding responsibility for PSA shifted to the federal government under the Revitalization Act. Prior to the implementation of the Revitalization Act, the District government typically allocated $3.5 million for pretrial services—this is the equivalent of $6.9 million in today’s prices. In Fiscal Year 2022, the budget request for this agency was $80 million supporting 325 full-time equivalent positions.

Adjudication: The D.C. Court System

The District’s Courts are made up of the Superior Court, the Court of Appeals, and the “Court System,” which provides technical and support services, including contracting and procurement, legal counsel, capital projects, facilities management, budget and finance, human resources, training, strategic management, information technology, and court reporting.19

The D.C. Court of Appeals, the highest court of the District of Columbia, has a single appellate court that serves dual roles as both an intermediate court of appeals and a court of last resort.20 The D.C. Superior Court is the trial court of general jurisdiction for the District of Columbia, handling all local trial matters. It also has a dispute resolution division, a social services division with a myriad of assistance programs for residents,21 and runs the Crime Victims Compensation Program.

Collectively the system employs nearly 1,500 employees including associate judges, magistrate judges, and senior judges, as well as professional staff. The court’s budget also includes defender services, which pays for legal and expert services for child abuse and neglect cases and the Guardianship Program, as well as defender services under the Criminal Justice Act (CJA).22

The structure and jurisdiction of D.C.’s courts did not change with the Revitalization Act. The appointment of judges was codified in Home Rule, and the jurisdiction of the courts was established in 1970 when Congress established the Superior Court and the D.C. Court of Appeals (DCCA) as separate courts for the District of Columbia.23

Funding the courts

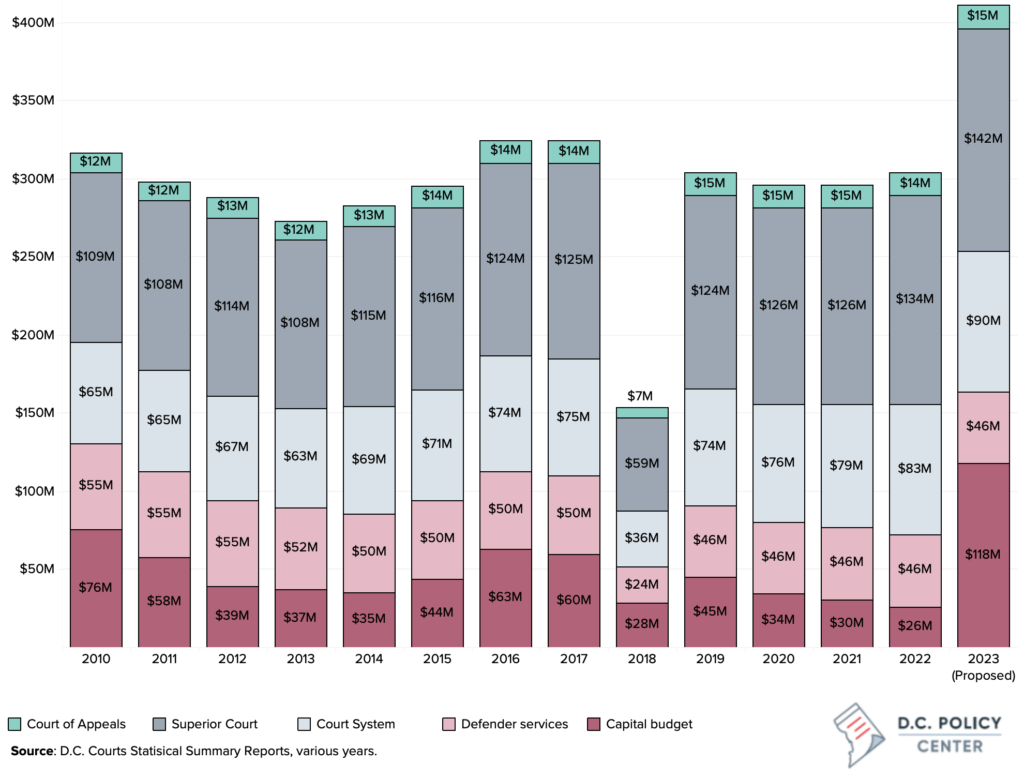

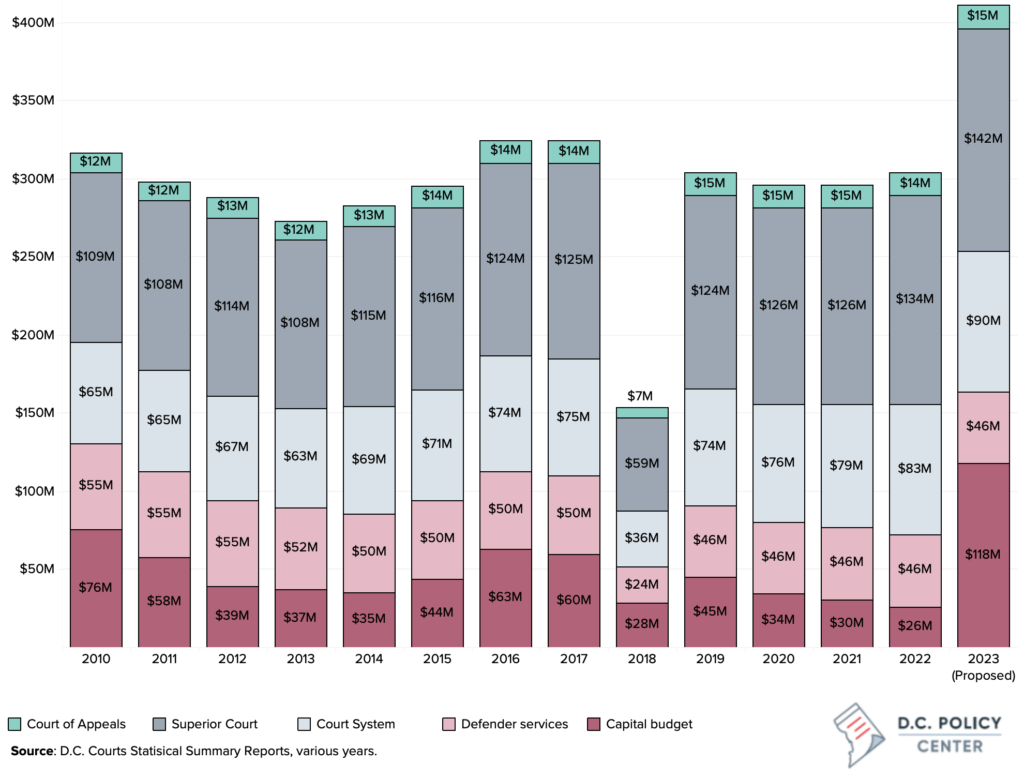

Per the Revitalization Act, the federal government funds the operations of the courts and maintenance of their infrastructure through Congressional appropriations. These include salaries and benefits for all staff, including the pension benefit contributions for all those eligible for a federal pension, as well as the funds necessary to maintain the buildings and IT infrastructure. At the time of the Revitalization Act, the District’s budget included approximately $110 million for the operating expenses of the court system, including the defender services. This is the equivalent of $217 million in today’s prices. The first year after the implementation of the Revitalization Act, the federal government appropriated $108 million for the courts and $43 million for the defender services, for a combined appropriation of $151 million or the equivalent of $272.8 million in today’s prices. In Fiscal Year 2022, the Court’s received $303 million of funding.

In addition, the federal government began contributing to the pension plan for the District’s judges. This amount was $5 million in 1999, and a Treasury Department report from 2019 show that the required contributions for the judges’ pension plan is about $15 million each year.24

While appropriations for the courts have generally increased over time,25 budgets have varied greatly, funding for defender services has declined since 2017, and the budget reduction of fiscal year 2018 caused a significant reduction of non-judicial staff (Figure 3).26 The fiscal year 2018 budget cuts resulted in a staff decrease of more than 100 positions (approximately 10 percent). While some of this funding was restored in later years, only 16 of these positions (primarily in juvenile probation supervision) were restored by fiscal year 2021 and nonjudicial staffing levels currently remain below 2017 levels.27

Figure 3. Annual federal appropriations for D.C. Courts, by fiscal year

Judicial nominations and vacancies

For long periods of time, D.C. Courts have had high rates of judicial vacancies, more than twice as high as federal trial courts, and the process for filling judicial vacancies is under federal control. As of December 2021, federal trial courts in the United States had an average vacancy rate of approximately nine percent.28 At that time, the D.C. Superior Court (DCSC) had 62 judicial seats, 14 of which were unfilled, resulting in a vacancy rate of over 20 percent. In the Court of Appeals, there are nine total seats and two vacancies as of December 2021, for a vacancy rate of 22 percent.29 Of note, there have been seven judicial confirmations in December 2022, six to D.C. Superior Court and one to the Court of Appeals, bringing the vacancy rate to 12 percent and 11 percent, respectively.30

The D.C. Judicial Nomination Committee—a committee made up of appointees by the President of the United States, the Mayor of the District of Columbia, the District of Columbia Council, two D.C. bar members, and Chief Judge of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia (a federal judge) —screens, selects, and recommends candidates for vacancies on the D.C. Superior Court and the D.C. Court of Appeals to the President, and the Senate confirms.31 While the President then has 60 days to nominate a candidate to the Senate, the Senate has no time limitations within which it must act.32 This practice has been in effect since the passage of the Home Rule Act of 1973.

Between 2013 and 2021, there have been five nominations for the Court of Appeals from the JNC to the President, with three names per nomination. This has resulted in one appointment in 2017 by President Trump. In the same time period, there have been 32 nominations from JNC for the D.C. Superior Court, which has resulted in 15 presidential nominations (9 by President Trump and 6 by President Obama).33

High caseloads and their impacts

High judicial vacancy rates, which are potentially the consequence of the current appointment process, create high caseloads for judges. And the issue of judicial vacancy rates in the District is particularly pressing now, as the number of pending cases has increased dramatically in the District due to

the COVID-19 pandemic. At present, the caseload is approximately 400 cases per judge in the civil division, when the ideal number is often cited as 250.34

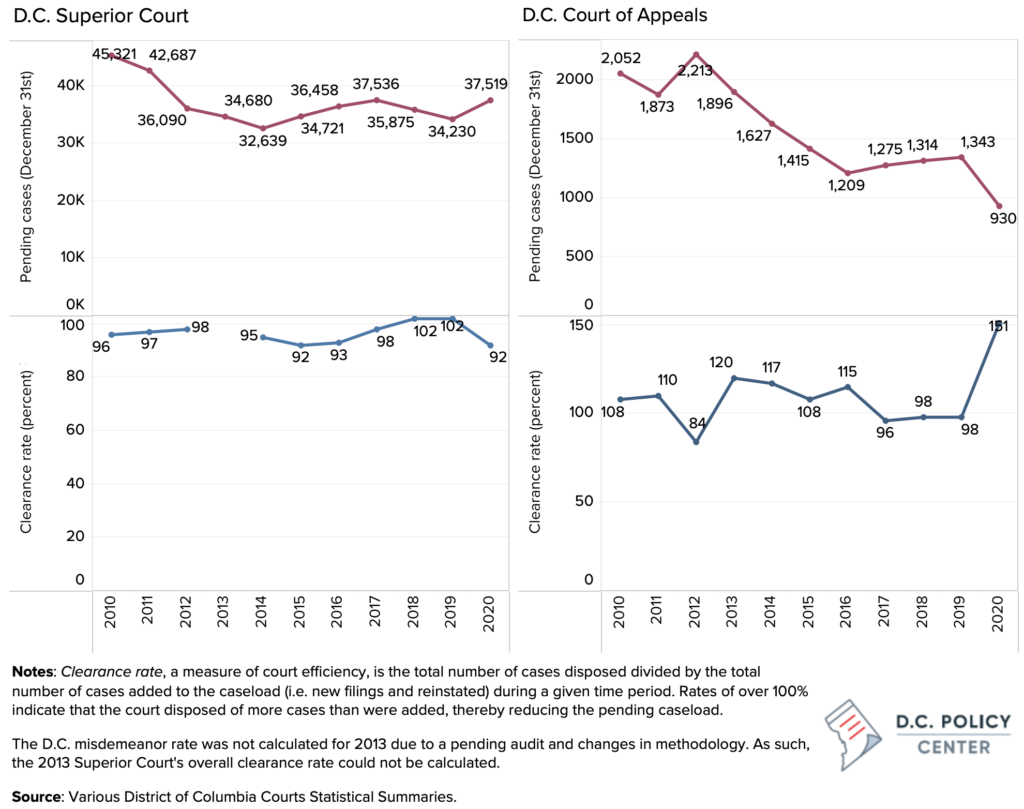

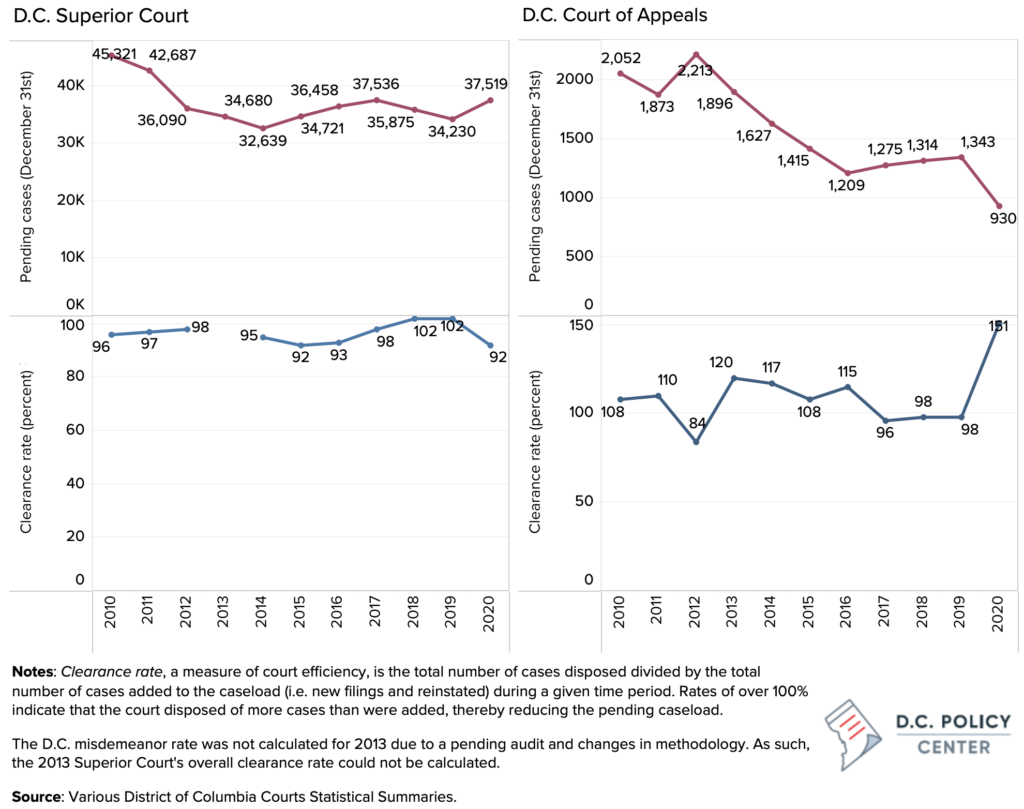

Additionally, D.C. had more than 10,000 criminal cases pending as of January 2022.35 This means that many trials have been delayed. Pre-trial wait times have gone up significantly since the start of the pandemic (March 2020), from an average of 90 days to 220 days,36 as trials were put on hold for over a year.37 The most recent publicly available data (from 2022) show that of the approximately 1,400 people being held under the custody of DOC, approximately 60 percent are awaiting trial. As of April 2022, men held in pretrial with felony charges spent an average of 13 months (390 days) incarcerated, while women held pretrial with felony charges spent an average of over eight months (257 days) incarcerated.38 Additional staff and resources may be necessary to help clear the backlog of cases that have built up. While both courts have been able to maintain a near-100 percent clearance rate (as of 2020)—meaning the judges have been able to dispose about the same number of cases as the number of new filings— they have not been able to significantly reduce backlog from previous years (Figure 4).39

Figure 4. Pending cases and clearance rate in D.C. Courts, 2010 to 2020

High caseloads cause administrative burdens on courts and can lead to burnout among judges. Additionally, studies have shown high vacancy rates to be associated with delays in trials and hearings, increased rates of prosecutors declining and dismissing cases, less time spent on cases, administrative burdens, and higher rates of guilty pleas.40

Sentencing: Truth in Sentencing Commission

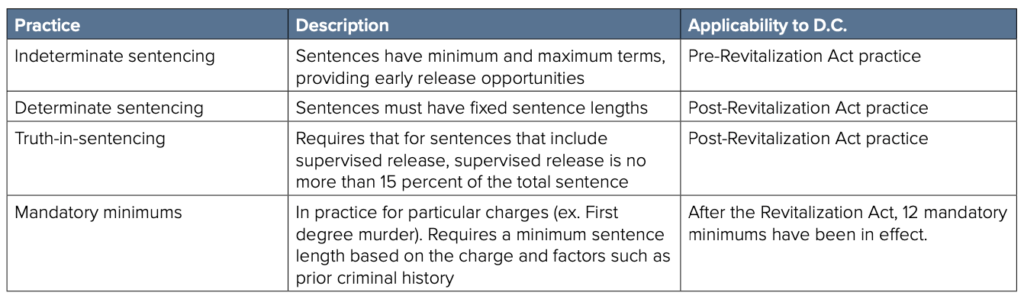

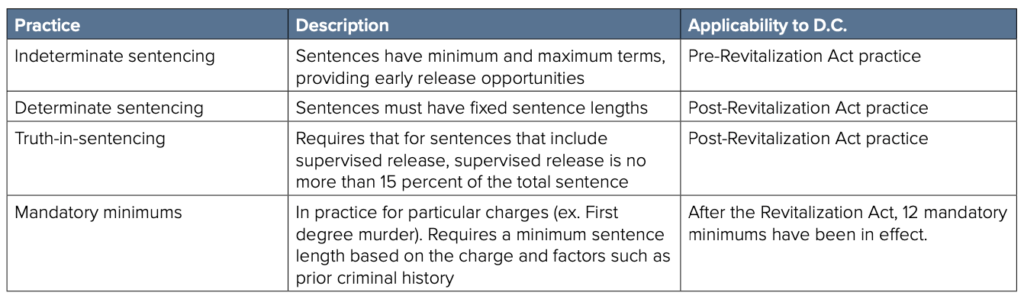

Federal interest in changing sentencing requirements precedes the Revitalization Act, beginning with the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act in 1994, which provided grants to states that enacted “truth-in-sentencing” policies.41 However, the District was not following this practice. The Revitalization Act required that the District update its criminal code and make changes to the District of Columbia’s sentencing practices to align them with truth-in-sentencing policies.

The Revitalization Act created the Truth in Sentencing Commission (TIS Commission) to make recommendations to D.C. Council and change D.C. Code sentencing rules, changing District sentencing from an indeterminate to a determinate sentencing system and requiring the District to rewrite its criminal code to meet federal “truth-in-sentencing” standards.42

In the pre-2000 indeterminate sentencing system, sentences for felony convictions provided minimum and maximum prison terms, with eligibility for parole following completion of the minimum sentence. For convictions after August 5, 2000, sentences must be determinate or have fixed sentence lengths. Determinate sentences may include a period of supervised release that is no more than 15 percent of the total sentence length.43 This proportion of amount minimum time that must be served in prison (85 percent of the sentence) is known as the “truth- in-sentencing provision,” and is in effect in many states around the country.44

Table 5. Sentencing practices in D.C. pre- and post-Revitalization Act

The federally-created Truth in Sentencing Commission made its formal recommendations to the D.C. Council in 1998, upon which its mandate expired. It was then replaced by the District of Columbia Advisory Commission on Sentencing (ACS), which was created by local act to make sentencing recommendations on the issues unresolved by the Revitalization Act.45 The ACS was replaced by the D.C. Sentencing Commission in 2004, which was then replaced by the D.C. Sentencing and Criminal Code Revision Commission in 2006. The Commission’s Criminal Code Revision mandate concluded on September 30, 2016. Because of the scope of needed reforms to D.C.’s criminal code, in 2016 the Council split the D.C. Sentencing and Criminal Code Revision Commission into two agencies, forming the D.C. Sentencing Commission and the Criminal Code Reform Commission (CCRC). The fiscal year 2022 budget for the Criminal Code Reform Commission is $907,000, funded locally.46

Over time, multiple changes have been made to D.C.’s criminal code, including the prevalence of mandatory minimums in sentencing guidelines. Before the Revitalization Act, the District’s mandatory minimums were limited to certain kinds of violent offenses and were occasionally increased in length. For example, the mandatory minimum sentence before parole eligibility for a person convicted of first-degree murder increased from 20 years to 30 years in 1992.47 After the Revitalization Act, 12 mandatory minimums were in effect, for crimes ranging from first degree murder to crimes when armed with a firearm and theft with more than one conviction.

In 2003, the Advisory Commission on Sentencing recommended the adoption of voluntary sentencing guidelines that work together with aforementioned sentencing practices. D.C. adopted these guidelines in 2004 in the Structured Sentencing System Pilot Program Amendment Act.48 Voluntary guidelines provide sentence length ranges based on the severity of the crime and prior criminal history. Judges can then impose sentences of probation, split sentences that include incarceration and supervised release, and prison-only sentences. Sentences can deviate from guidelines for ’unusual circumstances,’ but all sentences must be at least the length of imposed mandatory minimums.49 This type of system includes mandatory minimum sentence lengths but is less rigid than traditional mandatory minimum systems.50

It is important to note that on November 15, 2022, the D.C. Council unanimously approved an overhaul of the city’s century-old criminal code that updates the definitions of criminal offenses, creates new grades of sentences based on the severity of the crime, eliminates most mandatory minimum sentences, and broadly expands the right to a jury trial for people charged with misdemeanors.51

Incarceration: Department of Corrections and Bureau of Prisons

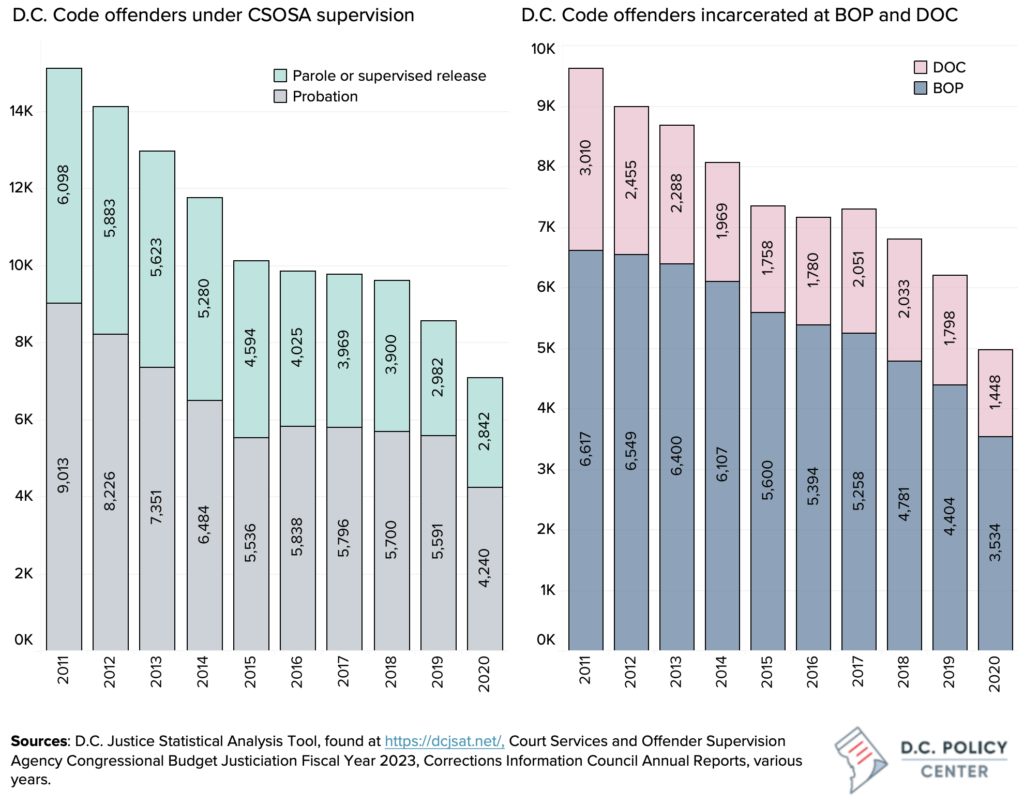

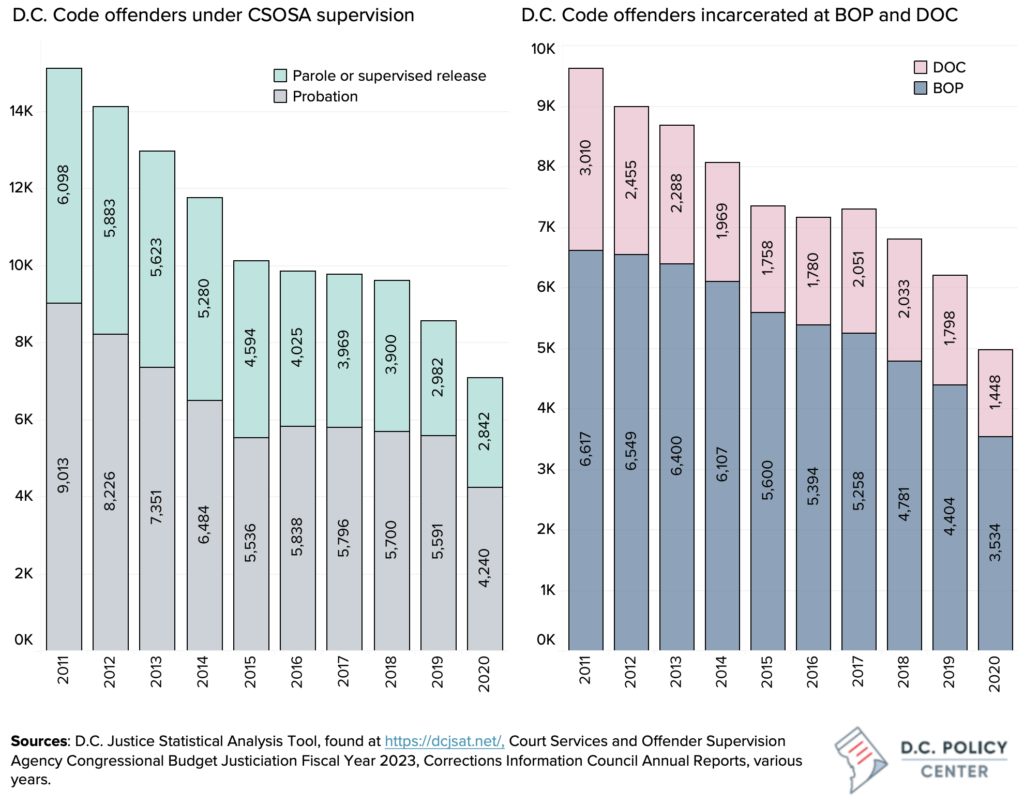

On a given day, over 22,000 residents of the District of Columbia can be justice-involved.52 As of August 2022, approximately 3,600 D.C. Code offenders were incarcerated, including 1,409 individuals in local jails under DOC custody, and 103 youth53 in local facilities.54 In addition, there are an estimated 9,500 D.C. Code offenders on probation, parole, or supervised release supervised by CSOSA,55 and approximately 4,000 D.C. Code offenders involved with the Pretrial Services Agency (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Incarcerated D.C. Code offenders in jail, under probation, parole, or supervised release 2011 to 2020

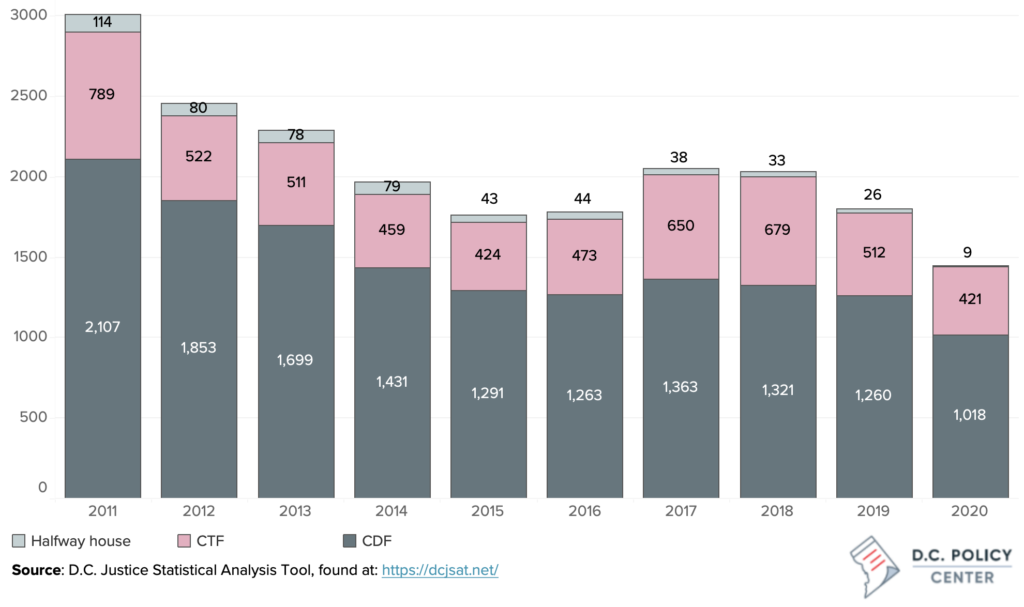

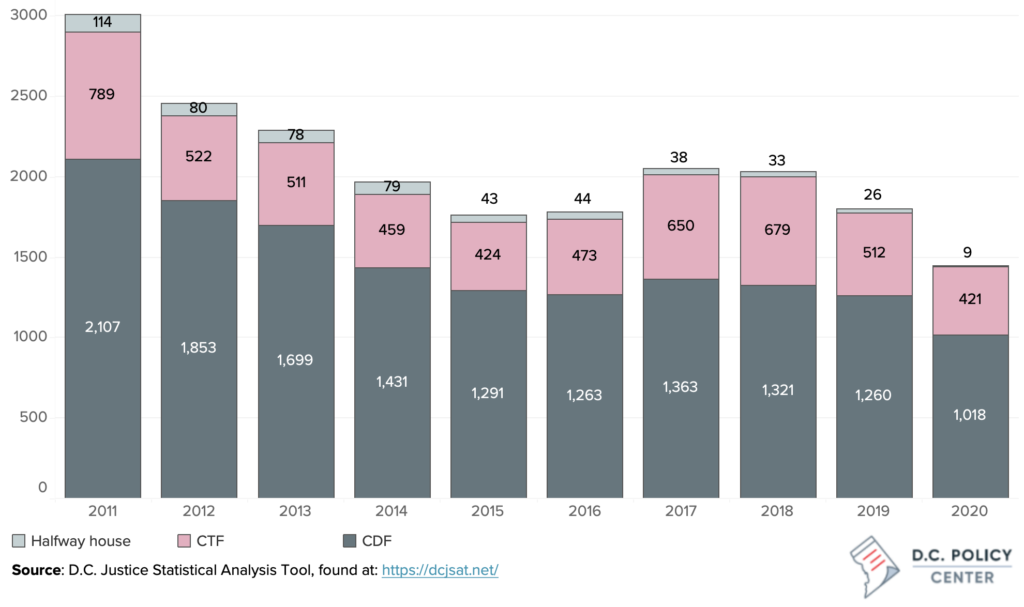

Department of Corrections

The D.C. Department of Corrections (DOC) operates two primary facilities, the Central Detention Facility (CDF), also known as D.C. Jail, and the Correctional Treatment Facility (CTF). These facilities are generally used for people awaiting trial and for people who received sentences of less than one year. The CDF opened in 1976 and was overcrowded from the start.56 57 Over time, the number of detained and incarcerated people in DOC custody has decreased, reducing problems of overcrowding. However, inspections have determined that other safety and health problems persist.58 For example, the U.S. Marshals Service is currently not holding people under their custody in D.C. Jail, citing conditions of the facility.59 Mayor Bowser’s most recent budget proposal (FY 2023) contained $250 million in capital funding to rebuild the CTF over the next six years, including $25 million to improve conditions for incarcerated persons in the CDF.60

The CTF opened its doors in 1992, next to the CDF, as a minimum to medium security facility with 1,400 beds for youth, women, and people with physical and behavioral health needs. The CTF operations were contracted to CoreCivic (formerly the Corrections Corporation of America) for 20 years, and DOC resumed control of the facility in 2017. The facility is currently used for treatment and programming for people in custody. As of 2018, no persons under 18 are housed in CTF, and instead are in the custody of D.C.’s Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services (DYRS).61

Additionally, BOP and DOC contract with privately operated halfway houses. Halfway houses are the last stop for incarcerated D.C. Code offenders returning from BOP custody. In D.C. there is one halfway house for women, called Fairview. The only halfway house for men in D.C., Hope Village, closed in 2020. People who could provide an address were released to home confinement. If no address could be provided, they were returned to prison or sent to a different nearby halfway house.62 BOP has contracted with an organization called CORE DC to open a new halfway house in D.C., but it has not opened yet.63

Figure 6. D.C. Code offenders in DOC custody by facility, 2011 to 2020

Bureau of Prisons

The Revitalization Act ordered the closing of the Lorton Correctional Complex, located in Fairfax County, Virginia, and transferred custody of D.C. Code offenders with a sentence of a year or longer to the Bureau of Prisons (BOP), to be sent to federal or privately run prisons.64 The last incarcerated person was transferred out of Lorton in 2001.65

While all D.C. Code offenders with sentences of over one year are held in Bureau of Prison (BOP) facilities, making BOP a large part of D.C.’s criminal justice system, D.C. Code offenders are a small share of the total BOP population.66 As of August 2022, there were a total of 157,775 total federal inmates,67 only 2,210 of which are D.C. Code offenders (1.4 percent).68 BOP has not attempted to place them in a single facility within the existing system, or a facility where their chances of rehabilitation could be maximized. Reports from the District’s Corrections Information Council often include observations of unmet needs for the District’s incarcerated residents as well as examples of discrimination and violence in federal facilities.

Parole: United States Parole Commission

The Revitalization Act transferred the authority over all decisions regarding the release of incarcerated District residents from the District’s own Parole Board to the United States Parole Commission (USPC) as of August 2000. This change also gave the USPC responsibility for revocation decisions for the supervised release of D.C. Code offenders.

The U.S. Parole Commission oversees a variety of populations. USPC has jurisdiction over federal offenders who committed offenses before November 1, 1987 and are thus eligible for parole;note]Importantly, in 1984, the Congress eliminated parole for federal defendants convicted of offenses committed after November 1, 1987. Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 was enacted as a part of the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 (Pub. L. 98–473, S. 1762, 98 Stat. 1976, enacted October 12, 1984.)[/note] Uniform Code of Military Justice offenders who are in the custody of the Bureau of Prisons; Transfer Treaty cases (United States citizens convicted in foreign countries, who have elected to serve their sentence in this country); state probationers and parolees in the Federal Witness Protection Program; and all D.C. Code offenders eligible for parole or serving sentences that include supervised release.

For D.C. Code offenders convicted before August 5, 2000, the United States Parole Commission has the power to grant or deny parole following the minimum determined sentence. For those convicted under the most recent sentencing rules, United States Parole Commission has the power to revoke community supervision if terms of release are violated.

Before the Revitalization Act, the USPC was set to be abolished. Parole was eliminated for federal inmates in 1984 and as the population of parole eligible inmates declined, USPC was set to be shut down by the early 2000s.69 With the passage of the Revitalization Act, the USPC gained a new population to oversee, but still must be reauthorized every two years.

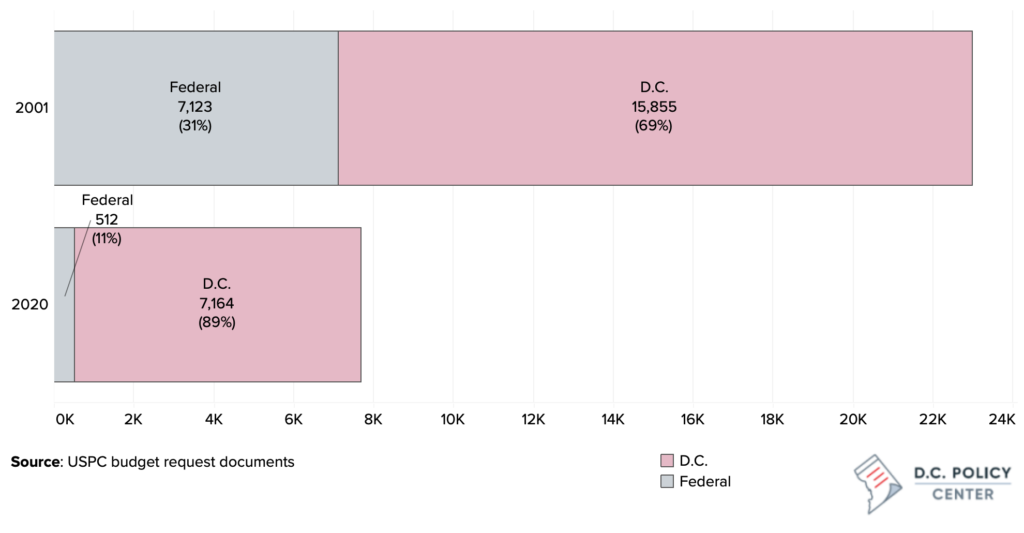

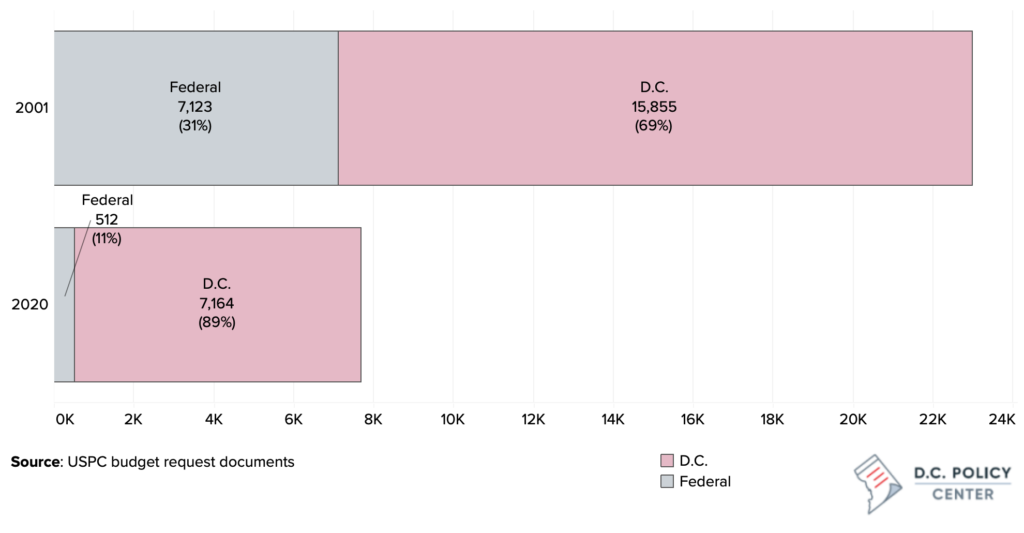

D.C. Code offenders make up an ever-increasing share of USPC’s caseload. In 2002, the USPC had 22,978 offenders under its jurisdiction, and District Code offenders made up 69 percent of this group.70 By 2020, the share had gone up to 90 percent (7,164 out of the total caseload of 8,019).71

Figure 7. USPC Case load, 2001 and 2020

It is hard to discern whether the USPC is better resourced than the District’s own Parole Board at

the time of its closure. At present, USPC’s budget is approximately $15 million, with potentially a large share of these funds dedicated to the management of the D.C. caseload. USPC also supports a Residential Substance Abuse Treatment Program (RSAT) which has operated out of the D.C. Department of Corrections since 2009 to deliver substance abuse treatment in a correctional facility setting as an alternative for offenders who would otherwise face revocation for low-level violations related to drug addiction and community reintegration failures.72 In the last year of its operation, the D.C. Parole Board was funded with $5.75 million (the equivalent of $11.75 million in today’s prices), but this also included funds for supervision.

There is no publicly available data on release decisions made by USPC, or on the length of sentences served. As such, there is no way to compare release and revocation decisions from USPC to decisions made by the D.C. Parole Board. However, caselaw and testimony suggest that USPC has sometimes deviated from the guidelines developed by the D.C. Parole Board.

Decisions regarding parole eligibility

D.C. Code offenders sentenced before August 5, 2000 received indeterminate sentences, meaning that sentences had a minimum and maximum term for incarceration. After completion of the minimum term of incarceration, D.C. Code offenders are eligible for parole.

The D.C. Parole Board based its release decisions on guidelines that were updated several times within its history. From its creation in 1932 until 1972, the D.C. Parole Board relied on language in the

D.C. Code.73 In 1972, the Board released a set of guidelines which consisted of a list of factors that the Parole Board was to consider when making decisions about release. These included prior criminal history, personal information including physical and emotional health, community resources available, and behavior while incarcerated.

This decision-making framework for parole was codified in the D.C. Municipal Code of Regulations in 1987. The 1987 Regulations included a point system based on the following four factors: severity of the current offense, salient factor score,74 negative institutional behavior, and program achievement.75 In this time period, sentencing operated in an indeterminate system, meaning that sentences had a minimum and maximum term for incarceration. In 1991, the Board adopted a policy guideline to define the terms used in the appendices to the 1987 Regulations to ensure their consistent application.76

Under the 1987 Regulations (and the accompanying 1991 Guidelines), the D.C. Parole Board granted parole to most D.C. Code offenders within 12 months of their minimum sentence. Using data from 1993 to 1998, researchers showed that the D.C. Parole Board granted parole to 40.3 percent of D.C. Code offenders at their initial hearing, and, if not released then, parole was granted to 61.4 percent of D.C. Code offenders at their first rehearing (hearings were usually conducted yearly).77 This implies that approximately 77 percent of D.C. Code offenders eligible for parole were released within one year of their initial eligibility date. Data suggest that a smaller share of D.C. Code offenders have been granted parole under the USPC jurisdiction.

When USPC took over parole decision responsibility from the D.C. Parole Board, guidelines for parole release changed from the D.C. Parole Board’s 1987 Regulations and 1991 Guidelines to the USPC’s 2000 Parole Guidelines. While the two sets of guidelines are similar in structure, in practice, the two systems could produce notably different outcomes due to differences in definitions and changes in scoring. Changes to the guidelines included a different scoring system that more heavily weighed the type of offense, changed definitions of program achievement and negative institutional behavior, and additional discretionary language.78

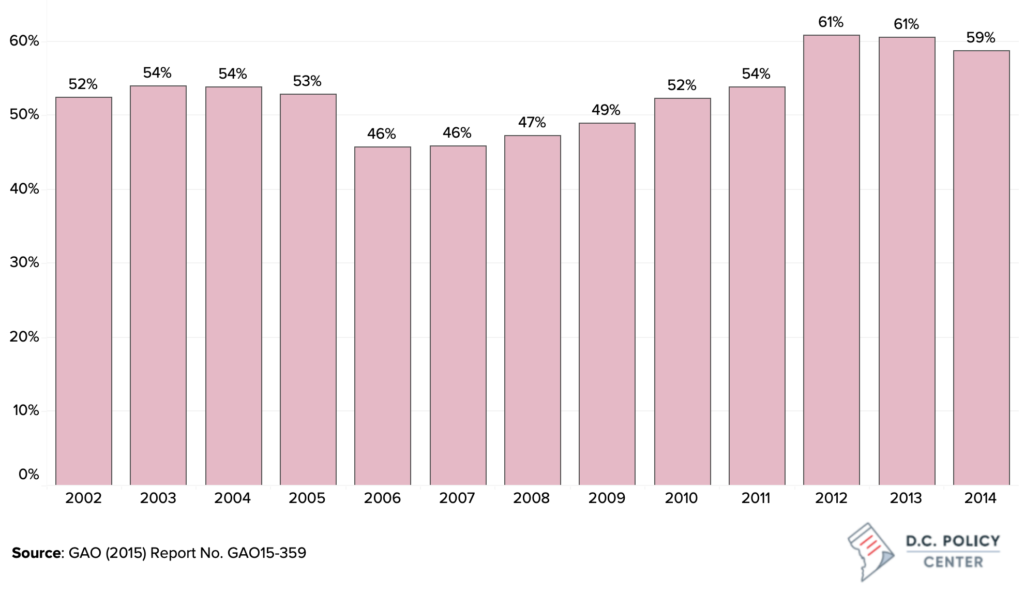

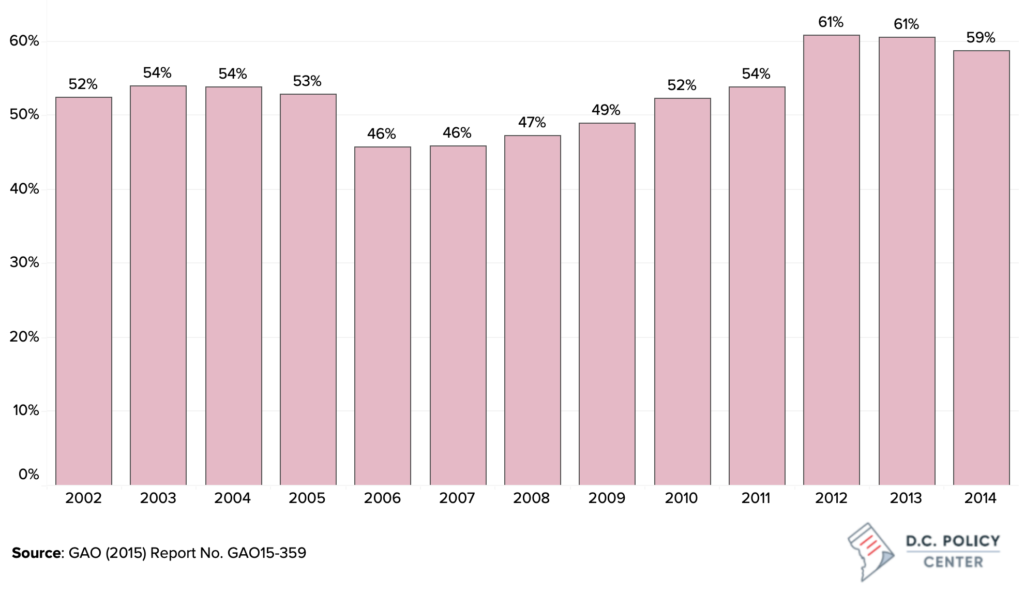

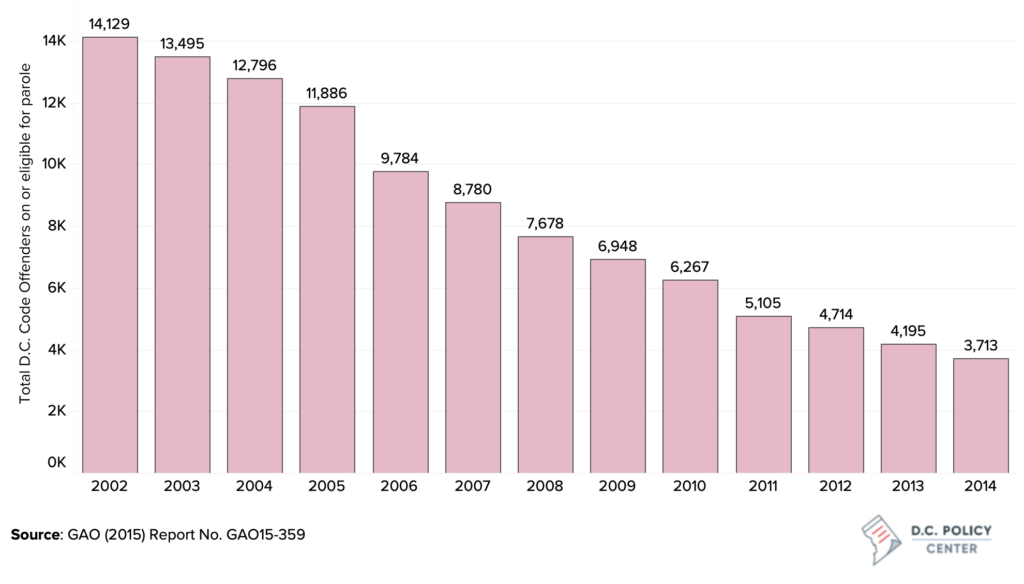

Data analyses conducted by the Government Accountability Office in 2014 show that between 2002 and 2014, on average 53 percent of D.C. Code offenders who are eligible for parole were on parole. The reduction in parole releases may be linked to the transfer from D.C. Parole Board to USPC. First, USPC hearings are generally conducted every three years, although current guidelines allow the commission to hold hearings every five years.79 The lower incidence of release could be related to the lower frequency of hearings. It could also be related to the declining parole-eligible population: as time passes, a higher share of D.C. Code offenders sentenced before August 5, 2000 would be serving longer sentences, associated with more severe crimes, and thus perhaps having a less favorable chance of obtaining a positive parole decision.

Figure 8. Share of D.C. Code offenders who are on parole, 2002 through 2014

There is some evidence that, at least for some parole-eligible D.C. Code offenders, the switch from the District’s 1987 Regulations and 1991 Guidelines to USPC’s 2000 Guidelines resulted in unfavorable parole decisions. In a 2008 legal challenge regarding the imposition of USPC’s 2000 Parole Guidelines to D.C. Code offenders sentenced prior to August 5, 2000 (Sellmon v. Reilly),80 U.S. District Court found that for some plaintiffs, the new guidelines used by USPC could result in an increased risk of prolonged incarceration, and granted rehearings to many plaintiffs sentenced between 1985 and 2000 who could factually demonstrate that the practical effect of the new policies substantially increased the risk of lengthier incarceration, given the particular facts of their case.81

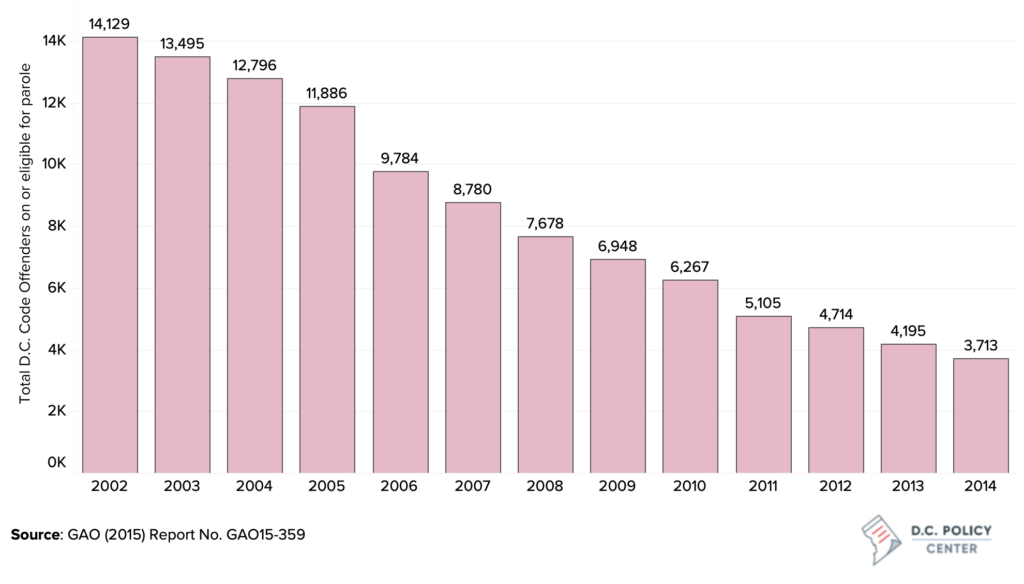

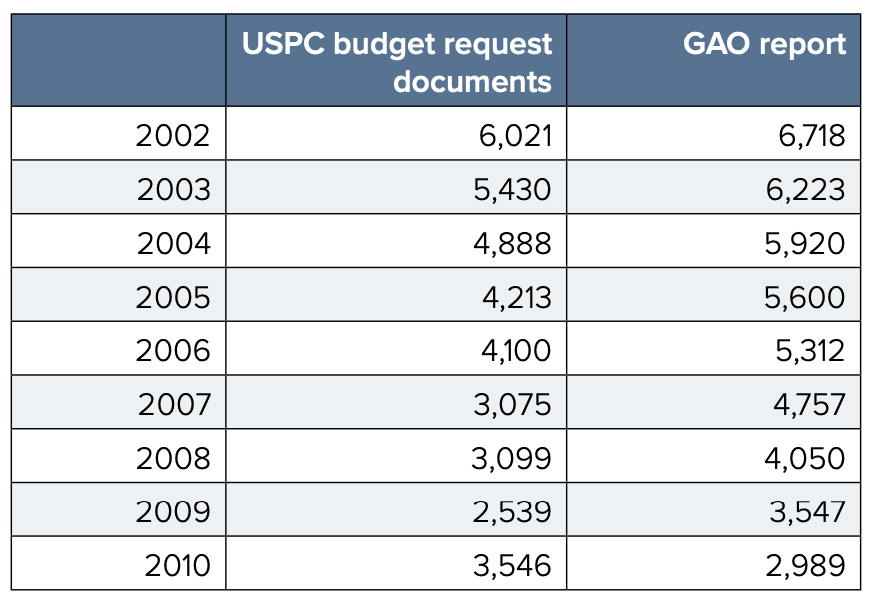

The research for this report could not identify in a single source that systematically tracked how many D.C. Code offenders were impacted by this court case, able to demonstrate that the new guidelines prolonged their period of incarceration, received a rehearing, and were eventually released. According to USPC’s performance review for the Fiscal Year 2011 budget, the interim rules for the Sellmon cases were put into place in September 2009. That year, USPC held 65 rehearings82 and the next year, it held an additional 34 hearings. The budget request narratives beginning in fiscal year 2013 no longer included this metric, and therefore it is not known if additional rehearings were held. That year, USPC also revised the number of incarcerated D.C. Code offenders who are eligible for parole, although we cannot be sure that this is related to the Sellmon rules.83

Figure 9. Number of D.C. Code offenders who are eligible for parole, 2000 through 2010

As of August 2020, there were 661 D.C. Code offenders in BOP custody who were sentenced

under the pre-Revitalization indeterminate sentencing scheme (before August 5, 2000), over half of which had past their parole eligibility date (345 people). Of the total population of D.C. Code offenders in BOP custody, there were 231 people for which three years had passed since their parole eligibility date, 180 people for which six years had passed since their parole eligibility date, and 129 people for which over 9 years had passed since their parole eligibility date.84

Decisions regarding supervised release

Sentences for D.C. Code offenders who were sentenced after on or after August 5, 2000 often include a period of supervised release following incarceration (incarceration must be at least 85 percent of their sentence). This allows them to return to D.C. under the supervision of a Community Supervision Officer but requires that they adhere to certain requirements like drug testing, maintaining employment, and regularly meeting with their supervising officer.

USPC has the authority to revoke supervised release if the terms are violated and can return individuals to prison for the remainder of the supervised release term. D.C. is the only jurisdiction in the U.S. with a board to decide cases on supervised release. In all other states, decisions on supervised release are decided by the courts.85 In fiscal year 2020, D.C. supervised release accounted for 63 percent of USPC’s work, D.C. parole accounted for 25 percent of USPC’s work, and federal code offenders accounted for 12 percent.86

CSOSA supervises all D.C. Code offenders on supervised release and submits requests for warrants to USPC if they determine that terms have been violated. Revocations can be due to ‘technical violations’ (which generally do not involve a criminal offense) such as missing meetings with their Community Supervision Officer, not submitting a drug test on time, testing positive for marijuana, and for new arrests, even if those arrests do not end in charges or conviction. D.C. Code offenders are often incarcerated while waiting for a hearing to determine if supervised release will be revoked, possibly affecting their employment, housing, and families. There is no publicly available data on USPC decisions regarding revocation of supervised release or length of incarceration following revocation of supervised release.

Officials at USPC noted that they have been working to reduce the number of revocations of supervised release. Changes have included reducing the average number of months of incarceration for revocations based on technical violations, as well as the implementation of an evidence-based system called the Short-Term Intervention of Success (SIS)/Pilot Project for Administrative Violators Expedited Resolution (PAVER). Ten years ago, there were approximately 750 people incarcerated for revocations, which is now down to under 100.87

Supervision Services: Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency for the District of Columbia

The supervision of D.C. Code offenders on probation, parole, and supervised release falls in the jurisdiction of the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency for the District of Columbia (CSOSA). CSOSA was established by the Revitalization Act and became an independent Executive Branch agency in 2000 following a three-year period of trusteeship, taking over the probation responsibilities formerly carried by the D.C. Superior Court Adult Probation Division. The Pretrial Services Agency (PSA) is a separate independent entity with separate allocations within CSOSA. Supervision functions are performed by the Community Supervision Program (CSP).

In FY 2021, CSP supervised 9,549 individuals, of which 90 percent were Black, 4 percent were white, and 5 percent were Hispanic. This population has high needs for support, as 7.5 percent had unstable living arrangements, 27.1 percent had mental health needs, 25 percent had substance abuse needs, and 68.5 percent were unemployed when they started supervision. Of the population CSP supervised between fiscal year 2019 and 2021, 55 percent were under probation, 30 percent were under supervised release, and 12 percent were on parole.88

D.C. Code offenders under probation typically remain under CSP supervision for nearly two years, D.C. Code offenders under parole for 12 to 18 years, and those under supervised release for typically longer than three years. The CSP caseload has decreased due to declining number of violent crimes in D.C., but the need for support remains high. The CSP programs have generally been successful: For example, in fiscal year 2020, of the 4,821 cases that exited, 71 percent of cases closed successfully, and 93 percent of closed cases did not result in revocation.89

When supervision was under the District’s jurisdiction before the Revitalization Act, its budget was included in the court’s funding, but program level funding that can help discern this amount is not available. In the first year of the implementation of the Revitalization Act, the federal government budgeted $43 million for supervision—or the equivalent of $76.3 million in today’s prices. It is unlikely that supervision received such a large budget when funded by the D.C. government in the 1990s.

The federal resources available for CSOSA’S Community Supervision Program have increased over time. In fiscal year 2021, this amount was $180 million. This level of funding, given the size of the population under supervision, is much greater than what states typically spend on community supervision. For example, New York’s supervision agency’s budget is approximately $140 million for the supervision of nearly 36,000 individuals.90 Minnesota’s community supervision program supervises 20,000 individuals and receives an annual budget of approximately $140 million.91

Conclusion

D.C.’s criminal justice system functions very differently than normal state systems, with significant federal involvement and funding. In practice, this means that agencies have separate goals, measures of success, funding sources and priorities, leaving a system that is not unified and frequently complicated to navigate and understand. The federalization of D.C.’s criminal justice system has significant impacts on the experience and outcomes for D.C. Code offenders, more information for which can be found in the main text of our report.

Editor’s note: In August 2023, this report was updated with a correction to Figure 1.

Endnotes

- There are many law enforcement agencies in the D.C. with the authority to place individuals under arrest, many of which are federal. Law enforcement agencies include the United States Secret Service, United States Marshals Service, United States Capitol Police, the Federal Bureau of Investigation. A list of agencies that cooperate with MPD can be found at Covered Federal Law Enforcement Agencies. (n.d.). Retrieved from https:// mpdc.dc.gov/page/covered-federal-law-enforcement- agencies#:~:text=The%20Police%20Coordination%20 Act%20covers,Squadron%2C%20Bolling%20Air%20 Force%20Base.

- For details, please see Public Welfare Foundation, “D.C.’s Justice Systems: An Overview.”

- The U.S. Attorney prosecutes most adult criminal cases in the Superior Court. In cases involving juveniles, traffic violations, or certain low-level “quality of life” misdemeanors, the Office of the Attorney General of the District of Columbia is the prosecutor.

- Council for Court Excellence and State Justice Institute, “Journalists’ Handbook to the Courts in the District of Columbia.”

- Moyd et al., Restoring Control of Parole to D.C.

- This office prosecutes federal crimes, a function also performed by the U.S. Attorney’s offices in other states. Unlike other offices, this office represents the United States and its departments and agencies in civil proceedings filed in federal court in the District of Columbia.

- Email received from USA Graves on April 22, 2022.

- These include local funds, special purpose funds, and dedicated funds.

- The federal funds largely support “Child Support Services” authorized under Title IV-D of the Social Security Act, which performs duties such as locating absent parents, establishing paternity, monetary orders, medical support orders, collecting ongoing support and enforcing delinquent support orders.

- The Public Defender Service, “Mission & Purpose.”

- PDS generally handles more serious criminal cases including felony cases, criminal appeals, parole revocations, and all defendants in the District of Columbia Superior Court requiring representation at Drug Court sanctions hearings. CJA attorneys (who are private attorneys who have been screened, put on a panel, and are paid on a case by case basis), handle less serious criminal cases.

- Interview with D.C. Superior Court, May 12, 2022.

- Public Defender Service Fiscal Year 2023 Congressional Budget Justification, (2022).

- Interview with DCSC, May 12, 2022.

- Public Law 89-519, 80 Stat. 327, enacted on July 26, 1996.

- Pretrial Services Agency for the District of Columbia. “Budget Request for Fiscal Year 2022.”

- Interview with Pretrial Services Agency, May 2, 2022.

- “Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency for the District of Columbia FY 2021 Agency Financial Report.” Budget and Performance (2021). Pretrial Services Agency.

- District of Columbia Courts. “2019 Annual Report.”

- D.C. is one of the 11 jurisdictions in the country with a single appellate court. For details, see D.C. Access to Justice Commission, “Delivering Justice: Addressing Civil Legal Needs in the District of Columbia,” 82.

- These include translation services, navigators, specialized services for veterans, services for disabled residents, mental habilitation advocates for residents with disabilities and mental health services for court participants. There are also services for juveniles, and civil and legal assistance programs. For details see District of Columbia Courts, “2019 Annual Report.”

- District of Columbia Courts, “Fiscal Year 2022 Budget Justification.”

- “History of the DC courts.” District of Columbia Courts.

- GAO, “United States Department of the Treasury District of Columbia Pensions Program Actuarial Valuation Report.”

- For details see Budget Request narratives for various years available on the D.C. Courts website.

- Justices are appointed by the president and thus outside of Court staffing authority to hire or let go. As over 75 percent of Court budgets go toward salaries and benefits, non-judicial staff had to be let go.

- FY 2022 Court budget justification.

- This includes justices of the Supreme Court, judges of the Circuit Courts of Appeal, judges of the District Courts, judges of the Court of International Trade, and judges of the United States Court of Federal Claims and the United States territorial courts. The federal judicial vacancy count on 12/1/2021. Ballotpedia.

- Alexander, K. L. (2022). “Biden nominates three new judges to D.C. Courts.” The Washington Post. Flynn, M. (2022). “Senate moves to confirm new D.C. judges amid vacancy crisis.” The Washington Post. Flynn, M.; Brice-Saddler, M. (2022). “D.C. courts ‘sound the alarm’ on judicial vacancies as local officials demand movement in Senate.” The Washington Post.

- Austermuhle, M. (2022, December 16). Senate confirms seven judges for D.C. Courts, addressing vacancy ‘crisis’. DCist. Retrieved December 20, 2022, from https://dcist. com/story/22/12/16/senate-confirms-7-dc-judges/.

- For details see Judicial Nomination Commission, “About JNC.”

- Other states are not reliant on congress or the President to nominate judges. While states can use a variety of methods as part of the judicial selection process, many states use a form of election at some level of court. In 22 states, judges are selected through either partisan or non-partisan elections, and in 16 states judges are appointed by the governor and subsequently go through retention elections.

- “District of Columbia Judicial Nomination Commission Report of Recommendations and Chief Judge Designations and Presidential Appointments to the District of Columbia Court of Appeals and the Superior Court of the District of Columbia May 8, 1975 to September 30, 2021.” Judicial Nomination Commission. (2021).

- Bannon, “The Impact of Judicial Vacancies on Federal Trial Courts.”

- This more than doubles 2020’s judicial caseloads, partly due to an over year-long pause in jury trials due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Flynn, M., & Brice-Saddler, M. (2022). “D.C. courts ‘sound the alarm’ on judicial vacancies as local officials demand movement in Senate.” The Washington Post.

- Interview with Pretrial Services Agency, May 2, 2022.

- Le Dem, G. (2021). “With jury trials on pause, a growing number of inmates are being held indefinitely at the D.C. jail.” DCist.

- “DOC Facts and Figures, April 2022″

- For details, see Budget Request narratives for various years available on the D.C. Courts website.

- Yang, “Resource Constraints and the Criminal Justice System: Evidence from Judicial Vacancies on JSTOR”; Austermuhle, “Judges Say ‘Unprecedented’ Vacancies At D.C. Court Are Slowing The Legal System | DCist.” Bannon, A. (2014). “The impact of judicial vacancies on Federal Trial Courts.” Brennan Center for Justice.

- “District of Columbia Sentencing Commission history and Timeline.” District of Columbia Sentencing Commission History and Timeline.

- The Revitalization Act required that the Truth in Sentencing Commission “to convert the District’s sentencing system for all subsection (h) felonies from an indeterminate system of minimum and maximum prison terms, with parole, to a determinate system with a single prison term imposed, at least 85 percent of which the defendant would be required to serve, followed by a period of supervision following release from incarceration.” This meant longer sentences in almost all cases. The Commission submitted its legislative recommendations to the D.C. Council on February 1, 1998. Because Council did not have the ability to amend this language—it could either fully accept the proposals or fully reject them—which would have allowed the Attorney General to adopt the final legislation in whatever way she deemed appropriate. The bill was enacted as the Truth in Sentencing Amendment Act of 1998 (DC Law 12-165; DC Code § 24-203.1 et seq.). For details, see District of Columbia Sentencing Commission, “History of the District of Columbia Sentencing and Criminal Code Revision Commission.”

- Truth in sentencing commission. “Truth in Sentencing Commission.”

- Ditton, P., Wilson, D. (1999). “Truth in sentencing in state prisons.”

- Advisory Commission on Sentencing Establishment Act of 1998, D.C. Law 12-167, D.C. Code § 3-101 et seq.

- “Fiscal Year 2022 Approved Budget and Financial Plan, Volume 2”. Office of the Chief Financial Officer. Page 509.

- Sabol, et al. Influences of Truth-In-Sentencing Reforms on Changes in States’ Sentencing Practices and Prison Populations, Final Report. NCJ 195161. Urban Institute.

- District of Columbia Sentencing Commission history and Timeline. “District of Columbia Sentencing Commission History and Timeline.”

- The District of Columbia Sentencing Commission. (2022). “Voluntary Sentencing Guidelines Manual.”

- Advisory Commission on Sentencing. (2003). Sentencing and criminal code revision commission 2003 Annual Report. “Sentencing and Criminal Code Revision Commission 2003 Annual Report.”

- Austermuhle, M., “D.C. Council approves sweeping overhaul of Criminal Code, though changes won’t take effect until 2025.”

- Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, “One-Day Estimate of Justice System Involved Individuals within the District of Columbia.”

- The number of youth who are justice involved has gone down significantly over time, from over 1000 youth to around 100 in 2022. This is largely due to diversion courts, prosecution choices from the Attorney General, and restorative justice programs. Interview with the Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services, May 2, 2022.

- Most but not all D.C. Code offenders are District residents. Additionally, individuals in DOC custody can include those under the jurisdiction of MPD, the US Marshal Service, and more. Census of Detained Justice-Involved Persons in the District of Columbia, August 3, 2022. Obtained from CJCC.

- Most recent data are from 2021. For details, see “CSOSA.” Also see Robin Selwitz, “Obstacles to Employment for Returning Citizens in D.C.” on the life outcomes of returning citizens under CSOSA supervision.

- District Task Force on Jails & Justice, “Jails & Justice: A Framework for Change.”

- In 2007, the CDF’s capacity was capped by DOC at 2,164 people. D.C Department of Corrections, “Correctional Facilities.”

- For details, see Patterson et al., “Poor Conditions Persist at Aging D.C. Jail; New Facility Needed to Mitigate Risks.”

- Lynch, S. N. (2021). “U.S. Marshals to remove 400 detainees from D.C. Jail due to poor conditions.”

- Gathright, J. (2022). “D.C. mayor Bowser’s budget proposal includes funding to replace troubled jail.”

- This practice ended with the passage of D.C. Law 21- 238, the Comprehensive Youth Justice Amendment Act of 2016.

- Many D.C. Code Offenders are currently placed at VOA Baltimore (34 out of 91 total as of August 3), 29 were in home confinement, and 9 in the Wilmington, DE RRC. Census of Detained Justice-Involved Persons in the District of Columbia, August 3, 2022. Obtained from CJCC.

- Lerner, K. (2020), “Closure of D.C.’s only men’s halfway house leaves residents scrambling for a safe place to live.”

- Revitalization Act at §§ 11202.

- The Washington Post. (2001), “Inmates moved; Lorton shut after 91 years.”

- The number of D.C. Code Offenders has decreased significantly over time, but it has always been a small subset of the overall population. The population has been decreasing as the number of people released significantly outpaced the number of people admitted. This has been further exacerbated by the pandemic, as there were no trials or court proceedings for over a year.

- BOP, “Federal Bureau of Prisons Population Statistics.”

- Census of Detained Justice-Involved Persons in the District of Columbia, August 3, 2022.

- Fulwood, I. “History of the Federal Parole System.”

- GAO, “U.S. PAROLE COMMISSION: Number of Offenders under Its Jurisdiction Has Declined; Transferring Its Jurisdiction for D.C. Offenders Would Pose Challenges.”

- U.S. Department of Justice, “U.S. Parole Commission FY 2021 Budget Request.”

- The RSAT program has a capacity of 75 beds for males, 25 beds for women, and a program length of up to 120 days, with 30 days of community-based inpatient or outpatient treatment.

- The language in the D.C. Code, which still exists today but is superseded by agency guidelines, states that for a release it must “appear to the Board of Parole that there is a reasonable probability that a prisoner will live and remain at liberty without violating the law, [and] that his release is not incompatible with the welfare of society.” D.C. Official Code § 24-404 (2001).

- Salient factor score (SFS) is a system that creates a number score between 1 and 10 based on the following 7 items: prior convictions, prior commitments, age at first commitment, whether the commitment offense involved auto theft or checks, whether parole had ever been revoked or the inmate is a probation violator, history of opiate dependence, and verified employment or full-time school attendance for at least 6 months during the last 2 years in the community. The higher the score, the higher the probability of release and lower risk of reoffense. Hoffman, P. B., & Adelberg, S. (1980). “Salient Factor Score – A Nontechnical Overview. Federal Probation,” 44, 1, 44-52.

- Browning, “Three ring circus: how three iterations of DC parole policy have up to tripled the intended sentence for DC Code offenders.”

- Op.cit. Ellen Segal Huevelle, District Judge, May 5, 2008. Sellmon v. Reilly, 551 F. Supp. 2d 66 (D.D.C. 2008).

- Sabol, et al. “Sentencing and Time Served in the District of Columbia Prior to ‘Truth-in-Sentencing’.” NCJ 191860.

- First, both guidelines use a point system called the Salient Factor Score (SFS), a system that creates a number score based on several items including prior convictions, prior commitments, age at first commitment, whether parole had ever been revoked or the inmate is a probation violator, history of opiate dependence, and verified employment or full-time school attendance for at least 6 months during the last 2 years in the community. The higher the score, the higher the probability of release. The 2000 guidelines adjust the SFS for the violence of the current offense, negative institutional behavior, and program achievement. Additionally, the 2000 guidelines include weights for criminal history, creating higher scores for people with a prior record, give a point benefit to being over the age of 41, and, unlike the 1987 guidelines, do not give a point boost to incarcerated people with no history of heroin or opioid dependance. All of these changes factor into the final Grid Score, which can determine parole eligibility. Second, the 2000 guidelines’ definition of negative institutional behavior is much more broad than previous definitions, encompassing many BOP administrative procedures and as much as tripling the amount of time before incarcerated people were eligible for parole. Every disciplinary infraction adds two months to each parole eligibility date, and any behavior that violates criminal laws could add anywhere from 8 months to 120 months to an incarcerated person’s sentence. Third, the definition of program achievement narrowed in the 2000 guidelines, from sustained effort and completion of an educational or vocational program to “superior” program achievement, a metric which has no definition in the guidelines. Even when achieved, “superior program achievement” can only subtract up to one third of the time spent in said programming from an imposed sentence. Fourth, the 2000 guidelines include language that affords additional discretion in parole decisions surrounding unusual circumstances, defined as “case-specific factors that are not fully taken into account in the guidelines, and that are relevant to the grant or denial of parole.” Steinberg, J., Ramsey, K. (2018). “2018 Parole Practice Manual for the District of Columbia.” Browning, “Three ring circus: how three iterations of DC parole policy have up to tripled the intended sentence for DC Code offenders.”

- Rodd, “D.C.’s Broken Parole System.”

- Tony R. SELLMON, et al, Plaintiff, v. Edward F. REILLY, Jr., Chairman of the United States Parole Commission, et al., Defendants. Civil Action No. 06-01650 (ESH).

- Sellmon v. Reilly, 551 F. Supp. 2d 66 (D.D.C. 2008).In 2016, a similar lawsuit, Daniel V. Fulwood required that USPC apply the D.C. Parole Board’s 1972 guidelines to D.C. Code Offenders sentenced before 1985. Daniel v. Fulwood, 893 F. Supp. 2d 42 (D.D.C. 2012).

- “United States Parole Commission Fiscal Year 2021 budget request,” Performance and Resource Table.

- It is important to note that data submitted to GAO in response to a data request show a different history. The table below summarizes the differences.

- People may be counted more than once in this data. For example, someone who is nine years part their eligibility date is also six and three years past. Council for Court Excellence. “Analysis of BOP data snapshot from July 4, 2020.”

- Interview with USPC, May 23, 2022.

- “United States Parole Commission Fiscal Year 2022 Performance Budget”, USPC.

- Interview with USPC, May 23, 2022.

- Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency, “Fiscal Year 2023 Budget Request.”

- CSOSA, “CPS Fiscal Year 2022 Congressional Budget Justification published on May 28, 2021.”

- See New York State Assembly Annual Report (2020) for more information.

- See Minnesota Department of Corrections: 2022-23 Biennial Budget (2021) for more information.