After years of encouraging its employees to work from home, the U.S. Agriculture Department recently scaled back its policy significantly, now permitting employees to telework just one day a week instead of up to four. The Education Department, too, implemented a new collective bargaining agreement earlier this year without any provisions on telework, leaving its status unknown.

While growth in telework throughout the D.C. region hasn’t come to a halt, surveys of area employees suggest there’s a lot of room for growth. In many ways, D.C. makes for an ideal place to telecommute. Traffic bottlenecks are a daily occurrence. Driving into D.C. is expensive, too, with I-66 tolls averaging about $12.65 round trip, not to mention parking fees.

How much telecommuting does or doesn’t proliferate over the longer term carries a litany of potential consequences for D.C., both positive and negative.

Telecommuting across the region

The latest “State of the Commute” survey published by the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments (MWCOG) found that 32 percent of non self-employed workers in the region at least occasionally worked from home or telework centers in 2016. That represents a steady increase, up from 25 percent of workers in 2010 and 27 percent in 2013.

Telecommuting, though, hasn’t nearly reached its full potential locally. The survey also reported 40 percent of commuters not working from home believed their job responsibilities would allow for telecommuting, and most of them expressed interest in telework if given the opportunity.

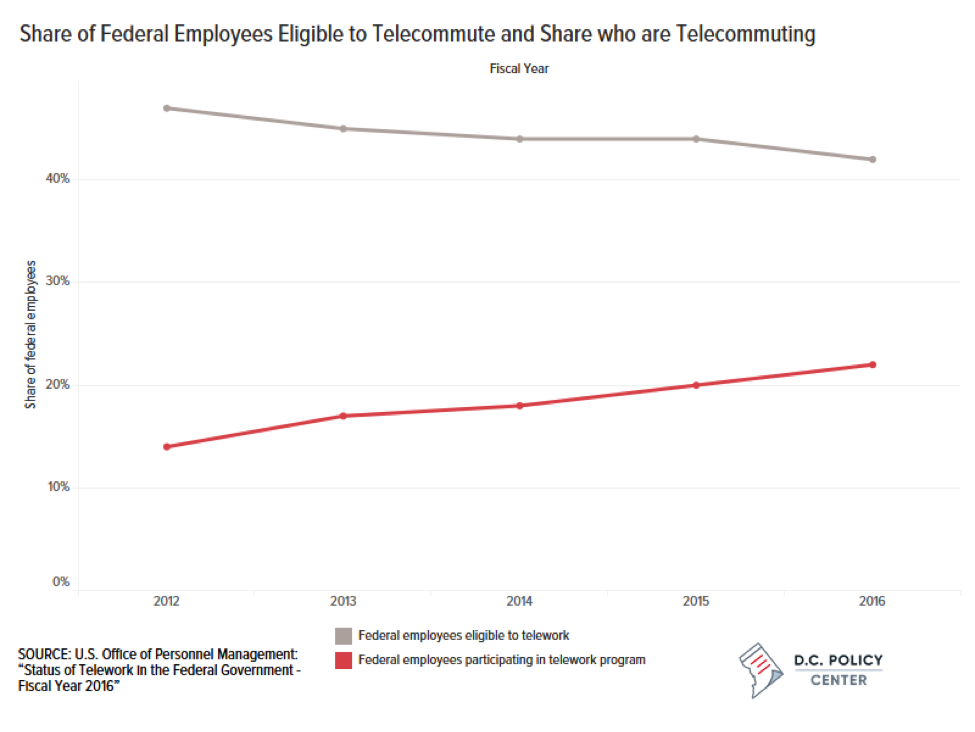

The single largest telework employer is, of course, the federal government. In its annual report on telework to Congress, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) noted the share of employees participating in telework programs continues to increase, with about 470,000 employees teleworking nationwide in fiscal 2106. However, the percentage of federal workers eligible for telework has remained flat recently and is actually down slightly from a few years ago. The OPM report says many agencies haven’t revisited eligibility criteria for telecommuting since first implementing their programs years ago.

Decisions by USDA and other large federal employers to eliminate or scale back telework programs, when taken together, amount to a lot of additional vehicles on area roadways. USDA officials told WUSA9 that more than 5,200 employees stationed at its D.C. headquarters and satellite offices in Maryland and Virginia telecommuted during a recent pay period, for example.

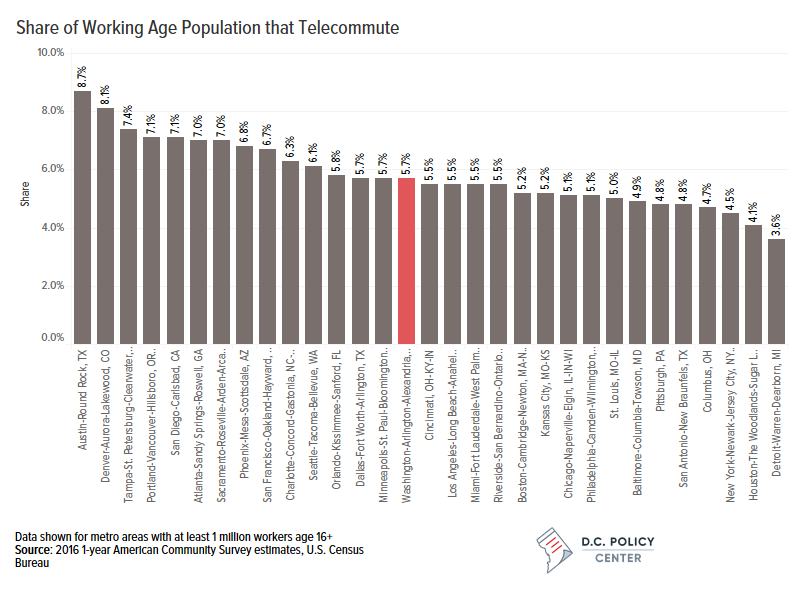

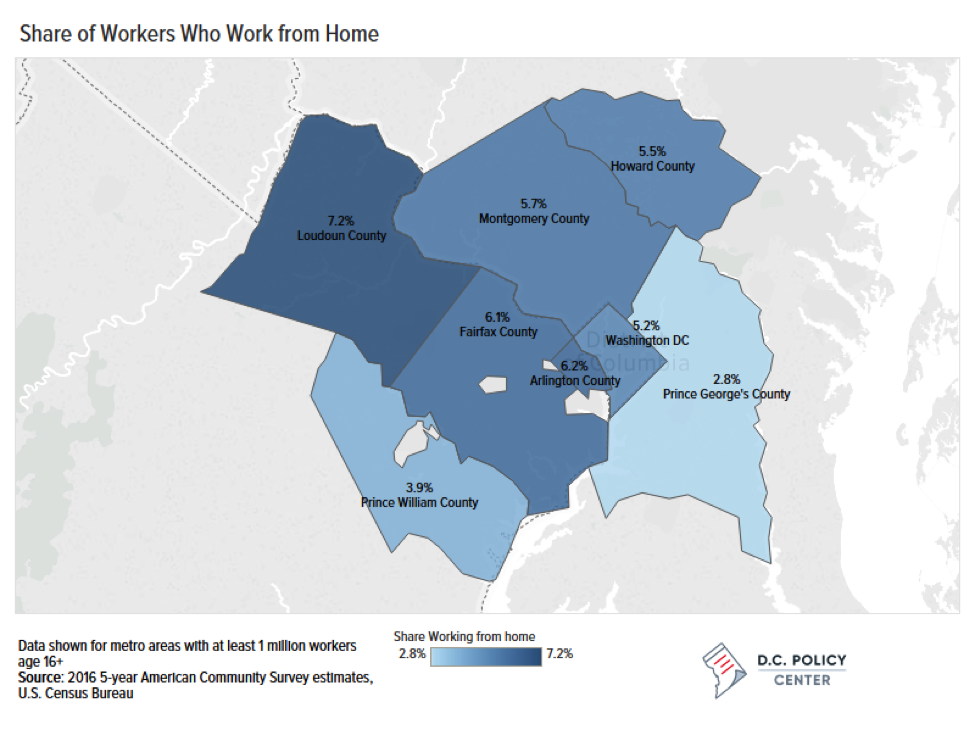

Nationally, Census data show more Americans are working from home. The latest American Community Survey (ACS) estimates suggest 5.7 percent of D.C. metro area workers worked from home in 2016. That’s a significant undercount of all people teleworking at least occasionally, though, as the survey asks respondents how they “usually” got to work and most teleworkers don’t work from home the majority of the time. (Self-employed workers are excluded.)

Compared to other large regions with at least a million workers, D.C. ranks in the middle of the pack. More than 8 percent of the workforce in Austin and Denver usually worked from home, while the share is even higher in select smaller regions.

Part of this simply has to do with how well a region’s major industries lend themselves to telework. Those working in insurance, real estate and tech jobs more commonly work from home, than say, hospitality workers.

The prevalence of telecommuting similarly varies across the D.C. region. The Census Bureau’s five-year ACS estimates suggest just over 5 percent of employed District residents primarily worked from home. By comparison, more than 7 percent of Loudon County’s workforce telecommuted, the highest share of any county locally. Part of this is likely due to it being a longer drive from employment centers, and that it’s not served by Metro rail. The smallest segment of the workforce teleworks from Prince George’s County, according to Census estimates.

The potential effects of these changes in telework practices

How much telework does or does not proliferate over the long term carries a number of potential consequences for the region. It’s worth considering what a few of the more pronounced effects could be.

For one, telework clearly takes vehicles off the road during peak commuting hours. The MWCOG survey found that telework, along with combined work schedules, eliminated 10.2 percent of work trips. The vast majority of those who didn’t commute to work reported they would have otherwise driven alone to their jobs.

Decisions by large individual employers to promote frequent use of telework can help curb vehicle-miles traveled over the course of a year. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, for example, reported to OPM that 5,995 of its area employees worked from home four to five days per week, while another 4,572 worked remotely one to three days. It all resulted in an estimated 89 million fewer miles driven in the region for the year, according to the agency.

Just how much telework may actually reduce congestion is difficult to approximate. Research tends to be mixed, with the effects ranging from fairly sizable to not noticeable at all.

For an extreme example, consider what happened when Pope Francis visited in 2015. Fearing heavy traffic, many workers stayed home for the day, and a MWCOG analysis later reported a 4 percent decrease in freeway volumes over the Pope’s two-day visit compared to the prior week. Congestion, though, declined by much more — 10 percent. The reduction was particularly dramatic during the height of the morning commute. Between 8 and 9 a.m., a 2 percent decline in freeway volume was coupled with a 27 percent drop in congestion those days. While a few days of a highly-publicized event don’t necessarily reflect a typical commute, it does suggest more telework may help lighten at least some of the area’s traffic woes.

Telecommuting yields some less desirable effects as well. A few studies have reported teleworkers make more trips during off-peak hours, such as to run errands. In some instances, it may also lead one to reside further from work. A German study and another published in Economic Inquiry last year both suggested telework promotes suburban sprawl. Accordingly, the MWCOG survey found telecommuting participation increased with longer commute distances, with 40 percent of those living 40 or more miles away from work teleworking at least occasionally.

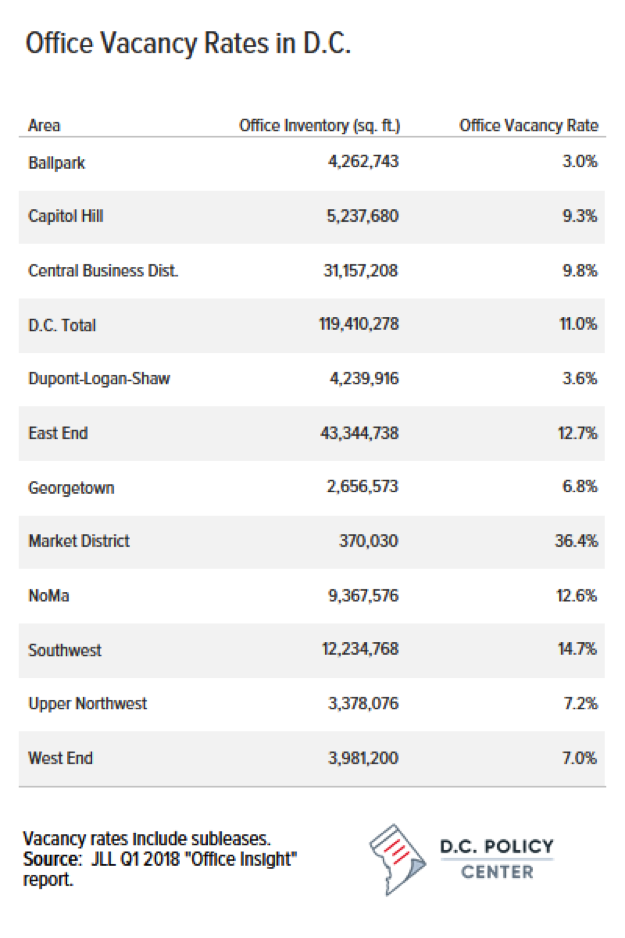

Given how much the D.C. government relies on revenues that rely on workers showing up in the city, a significant increase in telecommuting, despite desirable outcomes, could spell problems for the city’s finances. Fewer workers commuting could limit D.C.’s commercial real estate growth, and it may already be doing so. Data reported by CoStar indicates the amount of occupied commercial office space in D.C. remains mostly flat, declining by less than 1 percent from 2012 levels. Office vacancy rates had similarly climbed every year before declining last year. To put this in perspective, real property taxes brings in $2.6 billion (34 percent of general tax revenue), and commercial property accounts for about half the total tax base (but more than than 67 percent of collections, because of the higher tax.) Deed taxes generate another $500 million, again largely from commercial transactions.

Additional figures reported by real estate firm JLL for the first quarter of the year show how office vacancies compare throughout the District. For the two primary commercial districts, the Central Business District recorded an office vacancy rate of 9.8 percent, while the East End’s rate was 12.7 percent. Part of this may be due to large, longtime tenants downsizing their space. The JLL report notes that the law firms WilmerHale, Baker Botts and Pepper Hamilton all recently relocated, reducing their footprints by anywhere from 25 to 50 percent.

A few line items in the District’s budget that rely, at least in part, on commuters could also take a hit over time if significantly more workers opt to regularly telecommute.

In fiscal year 2017, the District’s budget figures show it collected at estimated $423 million in sales taxes levied at restaurants, a lot of which stems from commuters buying lunch or going out after work. An 18 percent tax on parking yielded another $74 million. These revenues are currently routed to WMATA, but a reduction in revenues means the District will have to make up the difference with other resources. Those caught speeding or running red lights during their commutes also contributed to D.C.’s budget, with traffic enforcement cameras generating $194 million in fiscal 2017. Parking tickets generate another $90 million.

Outside the real property taxes, the items related to commuting to D.C. are a relatively small portion of D.C.’s $7.9 billion general revenue. But they are still important: While select cities share income taxes with an employee’s place of work or have enacted commuter taxes, Congress prohibits the District from doing so. As a result, the District’s tax structure (with higher tax on commercial property, taxes on unincorporated businesses, high parking taxes, and high restaurant taxes) are designed to indirectly raise revenue from commuters.

And while there certainty is unused office space, D.C. remains a desirable place to locate. According to JLL’s figures, office vacancy rates still remain much lower in the District (11 percent) than northern Virginia (19.9 percent) and suburban Maryland (17.4 percent). So although some employers may downsize their office space or move out, it’s likely that others will readily take their place given D.C.’s desirable location and proximity the federal government, transit and other amenities.

About the data

MWCOG Survey: Telework employees are considered wage and salary workers reporting they at least occasionally worked from home or a telework/satellite center for a day rather than commuting to their usual place of employment. It excludes those working at client sites and those who travel to customers throughout the day.

Federal Employee Teleworking: Figures represent totals from 78-82 agencies reporting data to OPM. Some agencies may have made changes over the years in how they track telework eligibility and participation.

Regional and Metro Area Data: The Census Bureau asks survey respondents how they “usually” got to work. Percentages shown refer to those not self-employed who reported they “worked from home” in table B08301 in the American Community Survey (2016 1-year estimates).

Feature photo by Ted Eytan.

D.C. Policy Center Fellow Mike Maciag crunches numbers and writes for Governing magazine on a variety of policy issues relating to state and local governments. He holds a master’s degree in public administration from George Mason University and undergraduate degrees in journalism and computer science from the University of Dayton. Follow him on Twitter at @mikemaciag.