FIVE | HOW CAN THE DISTRICT USE ITS EXISTING RENTAL HOUSING TO CREATE INCLUSIVE NEIGHBORHOODS?

Up to this point, this report has provided extensive information on the District’s rental housing. It has shown that there are too few rental apartment units to house all renters, and the paucity of units is squeezing both high-income and low-income renters into the moderately priced units in the middle. Furthermore, while the rents for District’s rent-controlled units are lower, the tenants who live in them are economically segregated from higher-income households.

This report’s analysis of the District’s rent-controlled stock has revealed two of its important strengths related to affordability and inclusion: the rent-controlled stock typically has lower rents than the uncontrolled stock, and it is present in every ward of the city, especially in areas where it is hard to produce or preserve affordable housing using public funds. A third feature of the rent-controlled stock is that it is resilient. While the District has lost somewhere between 15 to 30 percent of its rent-controlled stock since 1985, this loss compares favorably to what has happened in other places with similar rent control laws.

This chapter therefore proposes a policy tool to take advantage of these characteristics in order to create designated affordable units with multi-year covenants. Because this tool uses the existing stock to create affordability and inclusion, it is referred to as the Inclusionary Conversion program.

Inclusionary Conversion program design

Under the Inclusionary Conversion model, the city would convert a small portion of existing rent-controlled units into designated affordable units. Once the conversion takes place, the converted unit would operate in the same way as an Inclusionary Zoning unit: the rent would be set below a certain income level that reflects the city’s affordability targets, and only households in the eligible income band would be offered the unit. In return, the landlord receives public support that is the equivalent of the difference between the rent-controlled rent and the affordable rent. This support can be in the form of a one-time subsidy during a capital event (much like a soft loan from the Housing Production Trust Fund), or in the form of annual subsidies through the covenant period (much like project-based local rent supplements).

Regardless of the financing approach, the Inclusionary Conversion program follows two simple principles:

- Use the rent-controlled stock to convert units into designated affordable housing, because they are everywhere, and their rents are relatively lower.

- Rather than committing an entire building for affordable use, convert a small share in each building to further establish economic inclusion without dramatically changing the overall income profile of a building.

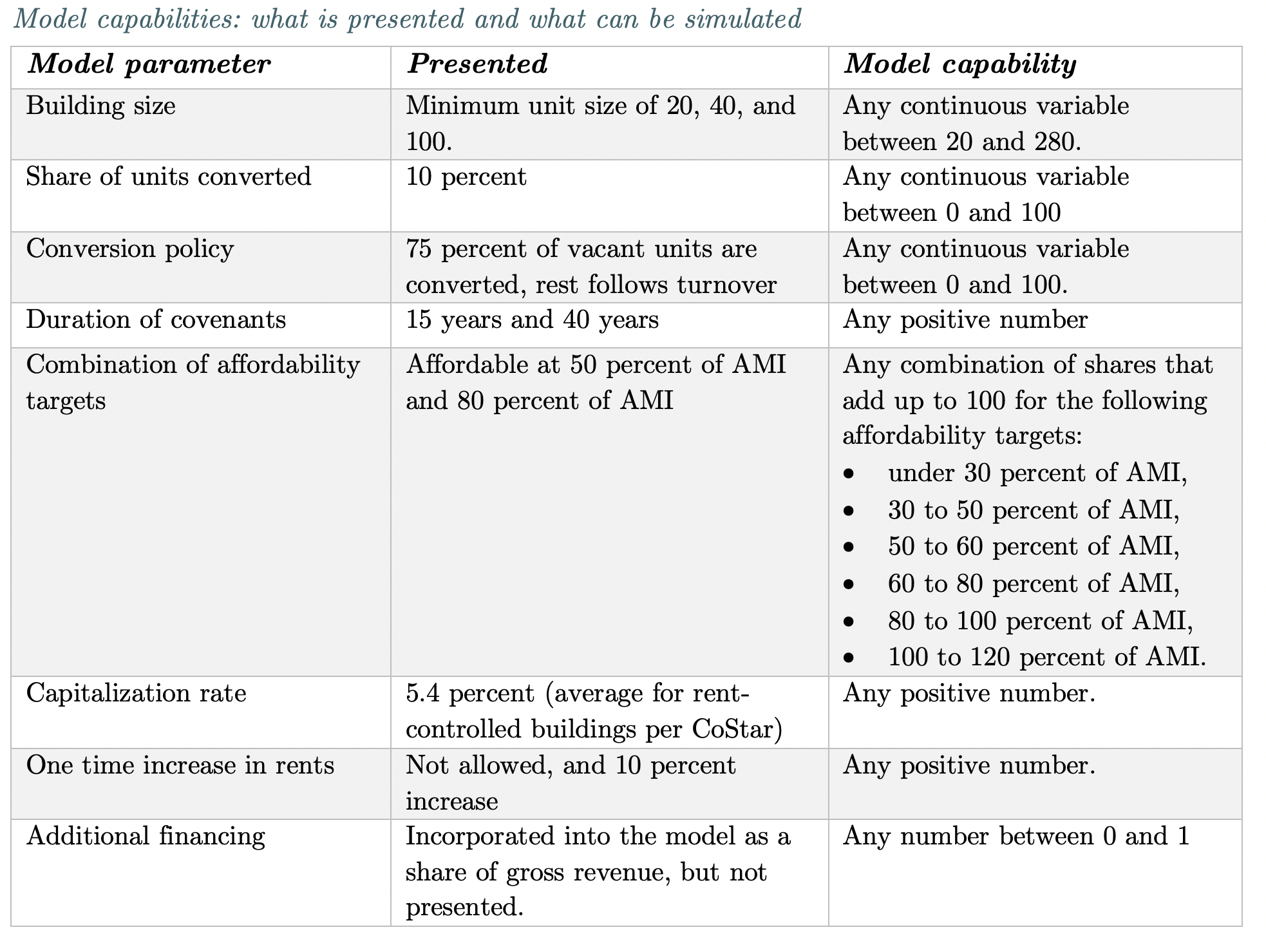

To estimate the how many affordable housing units the Inclusionary Conversion program could produce, and at what cost, the D.C. Policy Center developed a simulation model. The section below summarizes the model’s parameters, while a more detailed explanation is presented in the Methodology Appendix of this report.

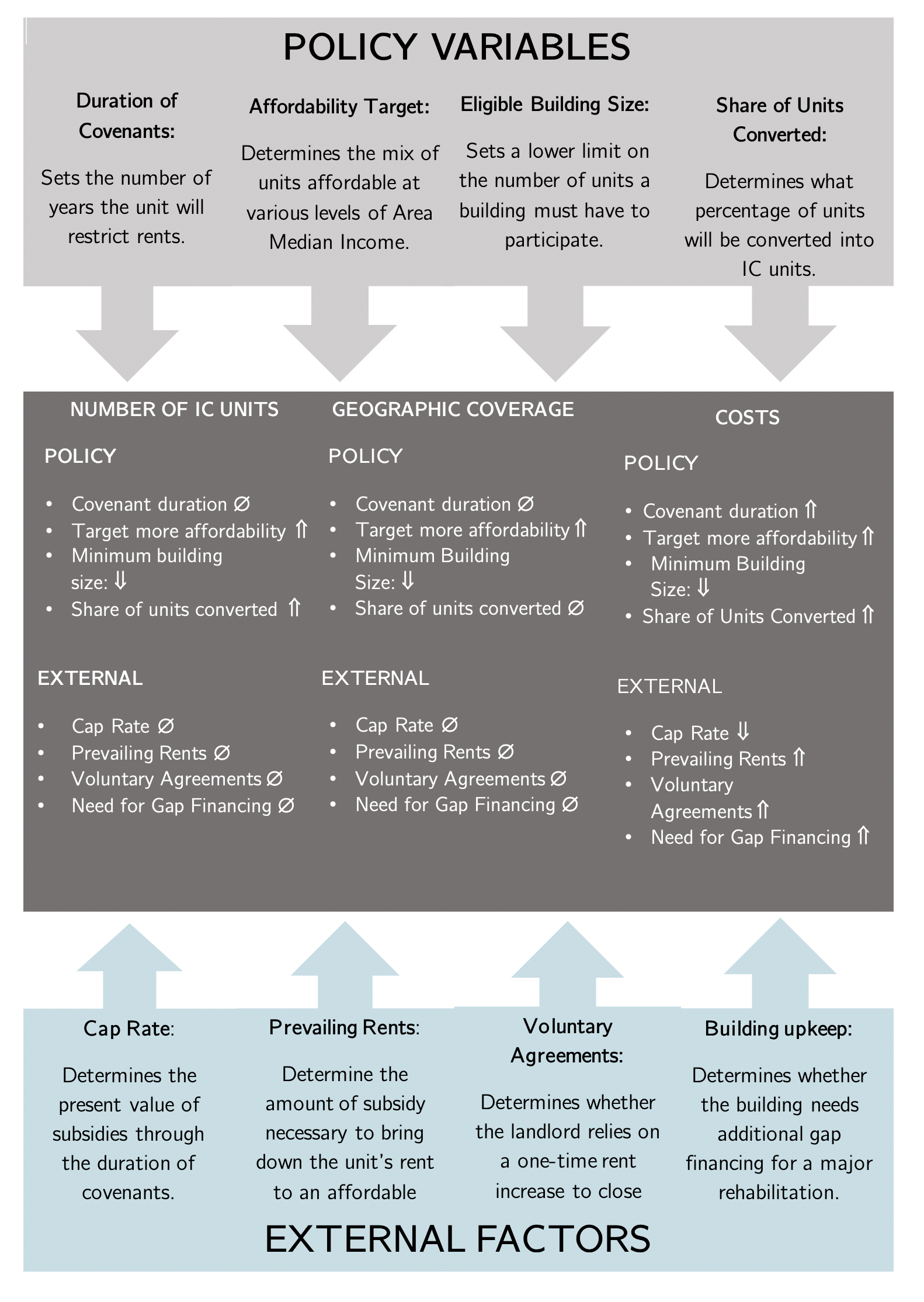

Policy Variables

The policy variables that could affect the number of units, their geographical coverage, and the amount of required subsidy (and therefore the cost of the program) include the following:

- Size or type of the buildings that would be included in the conversion program. For example, the District of Columbia might limit the program to larger buildings (based on the number of units in a building), older buildings (based on the year of construction or major renovation), or even location. As an example, this report only models the building size measured in units: a higher threshold for the required number of units reduces the number of eligible buildings, thereby reducing the potential number of Inclusionary Conversions, and shrinks the geographical coverage, mostly away from east of the Anacostia River communities. But it would not be difficult to extend the analysis to include age, proximity to transportation corridors, or location.

- Share of units that would be converted. This policy variable determines how much of a building is put under rent caps. A higher cap will convert more units, at a higher cost. A higher cap, if it overwhelms the building, can also significantly alter the revenue from uncapped units. This report models a 10 percent cap (the midpoint of current Inclusionary Zoning requirements).

- The conversion policy. Because the Inclusionary Conversion would apply to already occupied buildings, they would have to be brought into the program as the units turn over. However, conversions could begin immediately if existing vacant units are converted. A higher share of vacancy conversions will create a greater number of conversions at the beginning of the program, but it would not change the number units, geographical coverage, or costs. To illustrate how existing occupancy and turnover can impact conversions, this report models a program that converts three quarters of vacancies every year.

- The duration of covenants. The District of Columbia must determine the number of years through which the units would be under affordability covenants, or otherwise set aside for affordable use. A longer duration means higher costs.

- The distribution of affordability targets. A policy focused on creating affordability for lower-income households would cap rents at a lower level, resulting in higher subsidy. For example, if the city set a goal of keeping units affordable at 60 percent of the Area Media Income, the rents for a studio apartment would be capped at $1,274.[1] Thus, a studio with a rent of $1,000 per month would not be eligible for a subsidy. But the same unit would become eligible if the affordability goal is set at 30 percent of Area Median Income since the required rent limit would be $637. In this way, an affordability target focused on supporting lower-income households would increase both the number of eligible units and the amount of necessary subsidy. The lower maximum allowable rents would also expand the geographical coverage of the program, expanding it to lower-rent parts of the city.

- Prevailing rents. As shown in this report, rents in rent-controlled buildings vary greatly across the city. The costs of conversion are necessarily higher for buildings where rents are higher.

- The capitalization rate (cap rate). The capitalization rate is used in commercial real estate to indicate the rate of return that is expected to be generated on a real estate investment property.[2] The cap rate only matters to the program if the District is financing Inclusionary Conversions through a one-time cash infusion at the time of a capital event, like a refinancing. A higher cap rate would mean a higher discount rate of future rents, and therefore lower costs to the city. Changes in the cap rate would only impact costs, and not the units or their geographical coverage.

- Presence of a voluntary agreement. A landlord could be considering refinancing as a direct result of a voluntary agreement that requires investments in the property. In this case, the refinancing would rely on future income from a one-time increase in rents that are beyond what would otherwise be allowed under rent control. If this were the case, then the subsidy costs for the city would increase because the gap between the market rent and the capped rent would be higher.

- Additional financing for major rehabilitation. The costs can also increase if the District provides additional financing for buildings that need significant renovations. This will bring the Inclusionary Conversion program closer in character to a preservation program, thereby ensuring that rent-controlled buildings in need of major rehabilitation stay under rent control. While the state of a building’s disrepair is not under the District’s control, the city can choose whether to include rent-controlled units that need major rehabilitations in the Inclusionary Conversion program.

How does the financing work?

The District can implement the Inclusionary Conversion program using two different financing approaches:

- Convert during refinancing with one-time funding. Under this approach, the District would implement the conversion following a capital event, such as refinancing. The value of the subsidy would be the present value of the amount of the rent the landlord forgoes (that is, the difference between the capped rent and the prevailing rent) over the duration of the covenants. The covenants would be recorded with the deed identifying the Inclusionary Conversion units (or defining the landlord’s responsibility) and the rules regarding rent caps. The District could require participation in the Inclusionary Conversion program (similar to Inclusionary Zoning) or set aside a certain budget for each year and ask for requests for proposals from landlords (similar to how the city distributes funding from the Housing Production Trust Fund).

- Convert with annual subsidies. Under this approach, District would commit to a financial subsidy over the duration of the covenants for all converted units. This could be cash payments for rent, tax abatements, or a combination of the two depending on the conversion rate and the city’s affordability targets. The program can be implemented in a manner similar to project-based local rent supplements, or it could be implemented gradually (or at once) across all rental buildings, if there are no legal impediments.

Under both approaches, the only pieces of information needed from the landlord are the prevailing rents and information on vacant units, both of which are easily verifiable.

Advantages of the program:

Regardless of the policy parameters and specific design choices, the program has the following distinct advantages:

- It creates many affordable units in parts of the city where existing affordability programs have not been successful. Because of where rental apartment buildings are located, the greatest number of conversions will be in Wards 1, 2 and 3.

- It has much lower costs to the city than most current affordable housing programs. Because the subsidy is covering the difference between the rent-controlled rent and the affordable rent, the costs to the government are much lower than most current housing programs. This is true whether the city implements it as an operating subsidy (similar to Section 8 voucher or tenant-based local rent supplement) or a one-time cash infusion following a capital event (similar to the HPTF loans for production and preservation).

- It has the potential to create a greater degree of economic inclusion than what has been created in the past. Because the program is focused on converting only a modest share of units in each instance, as opposed to entire buildings, it creates economic inclusion in each participating building by bringing tenants of different income levels into the same building.

Potential number of units and the unit pipeline

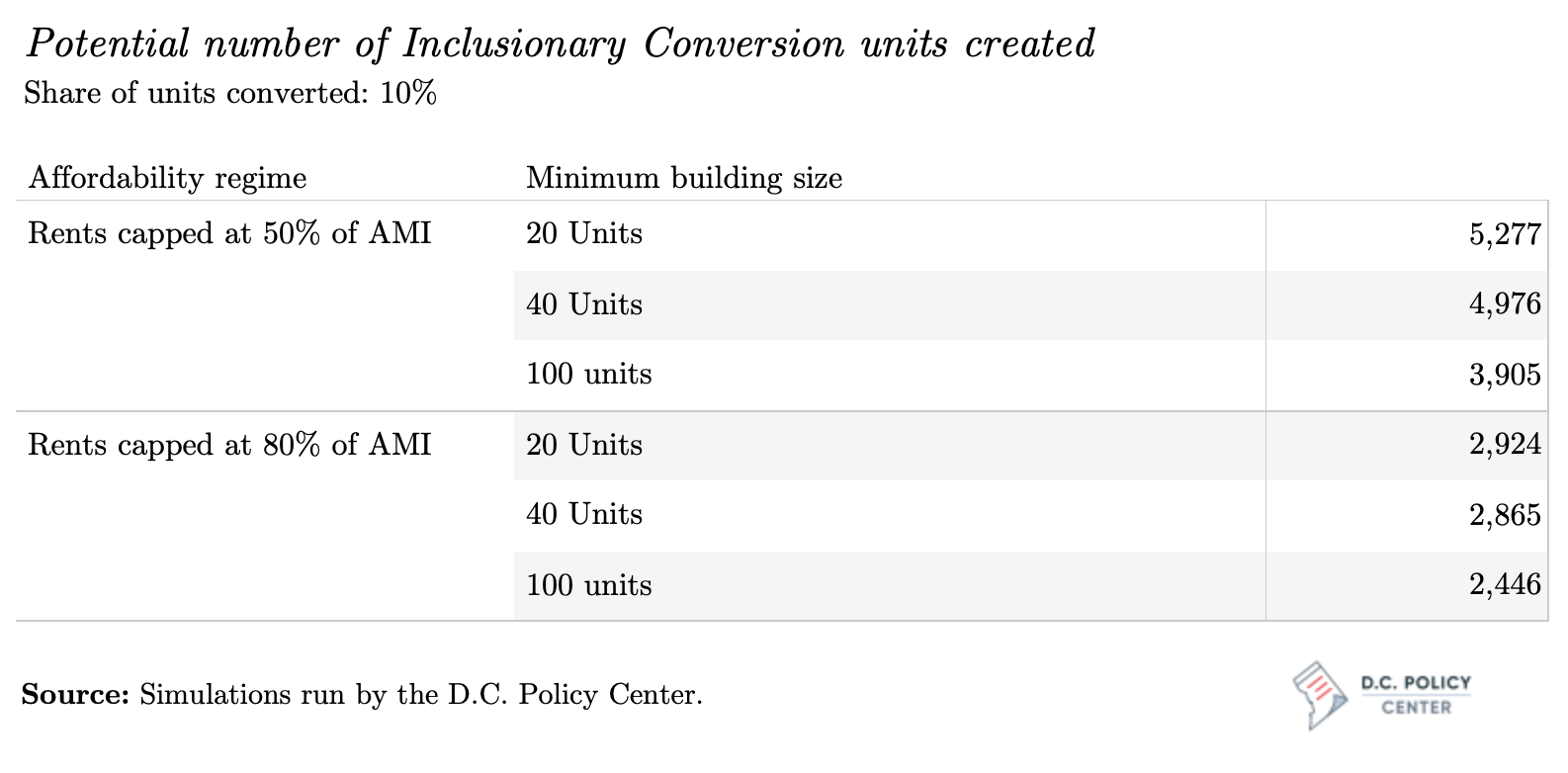

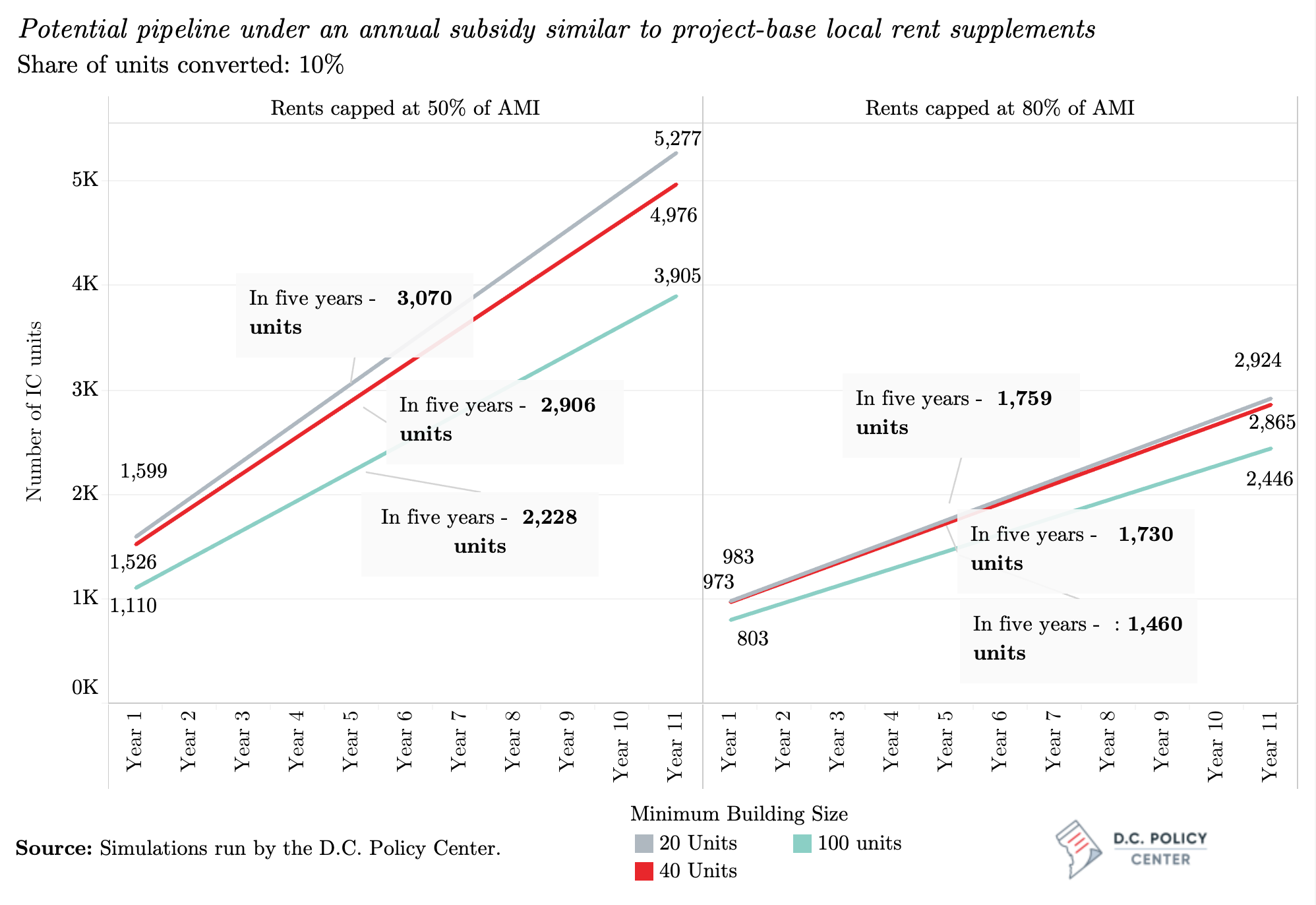

The potential number of units depends on the share of units set aside for covenants, the minimum size of buildings included in the program, and the affordability target. The D.C. Policy Center has developed a model that can be simulated for different combinations of policy levers (Table 3). For illustrative purposes, this section presents the estimated number of units under two different affordability targets (capping rents at 50 percent of AMI and 80 percent of AMI) with three different size limitations for eligible buildings (with a minimum of 20 units, 40 units and 100 units). This example uses 10 percent as the share of units that would be converted—that is, the midpoint of current Inclusionary Zoning requirements.

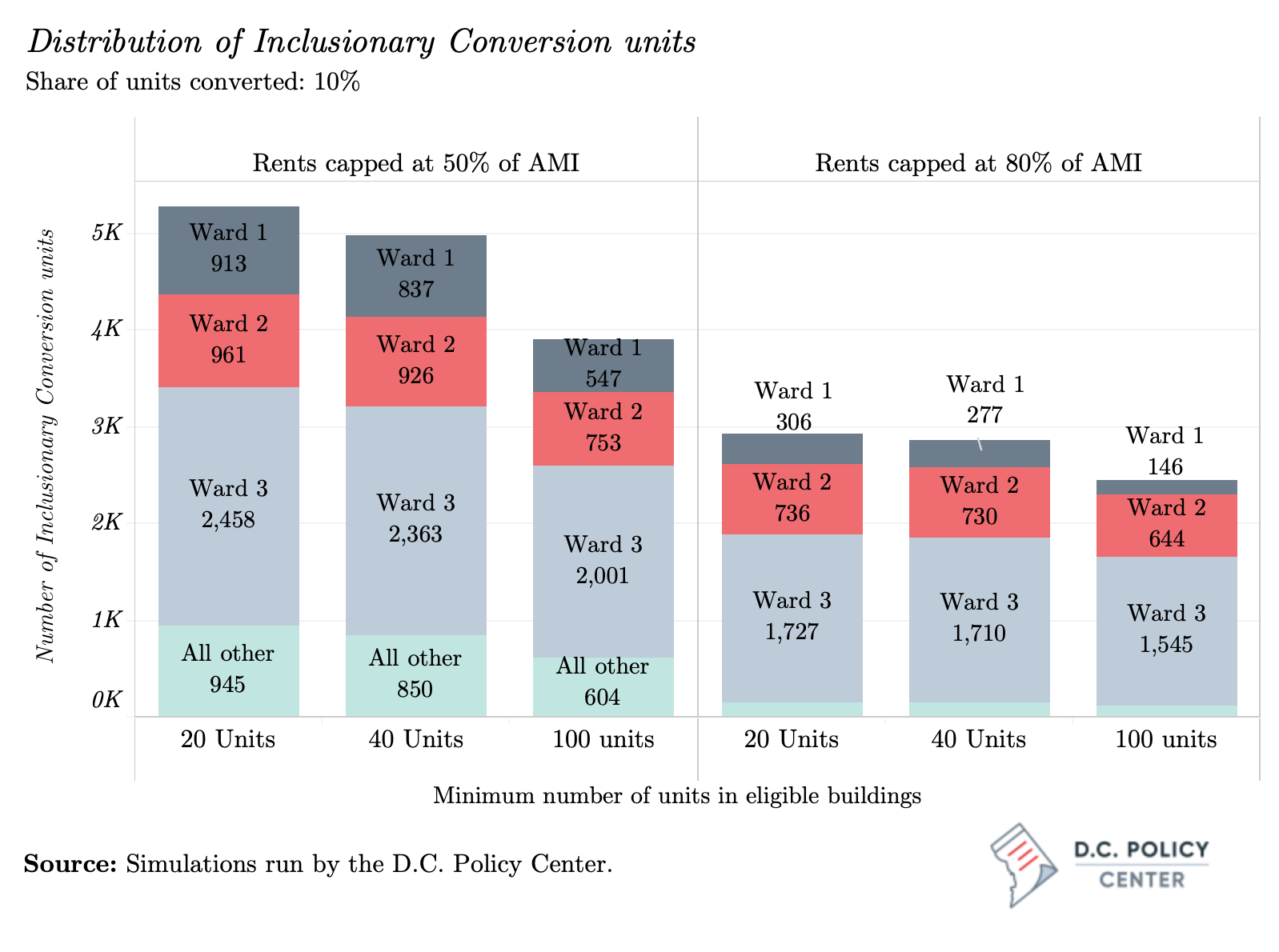

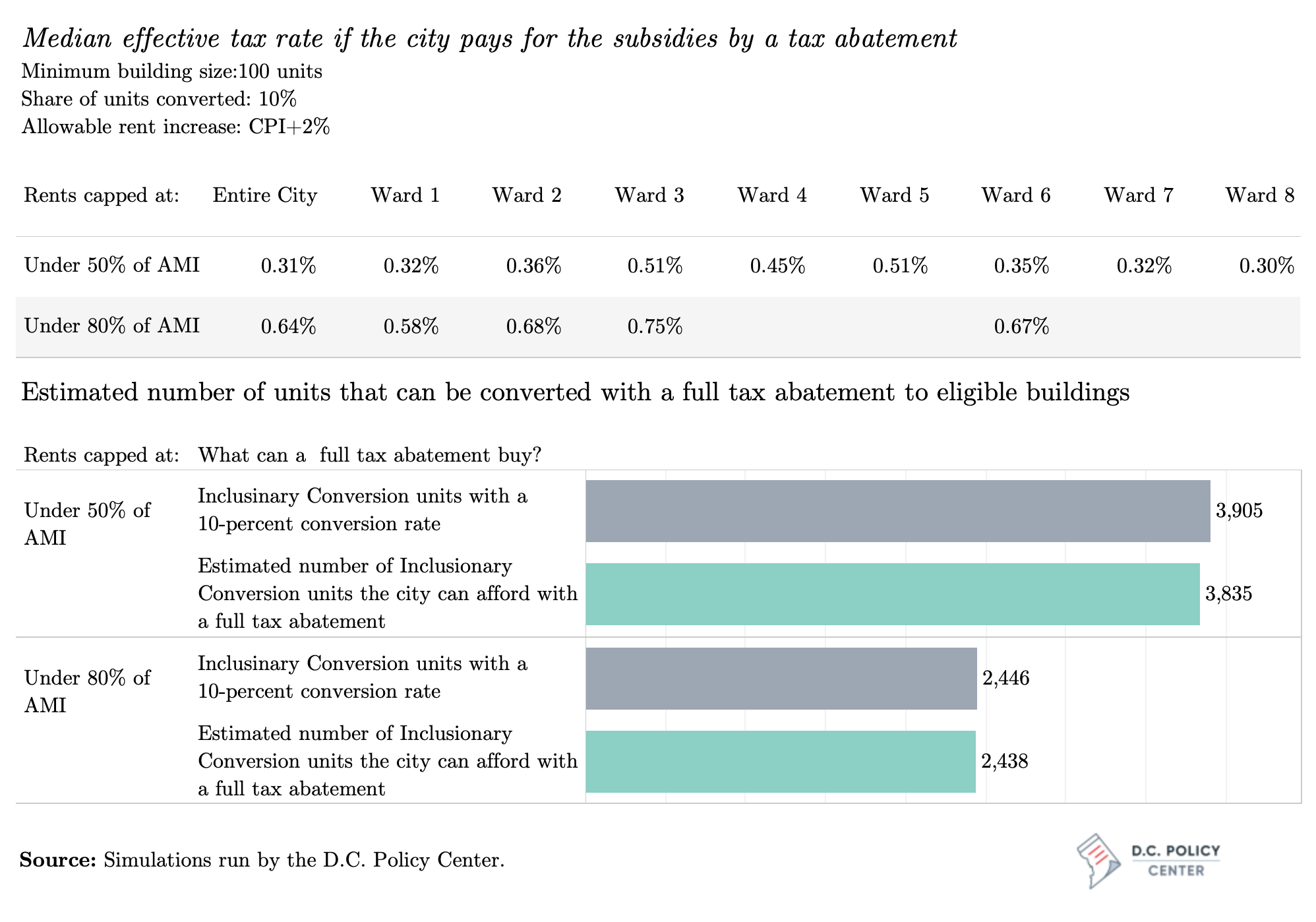

The figure below the results of these simulations. It shows that with the deeper affordability target of 50 percent of Area Median Income, the District can produce an estimated 3,905 Inclusionary Conversion units if the program is limited to large buildings with 100 or more units, and nearly 5,300 Inclusionary Conversion units if the program is expanded to buildings with 20 or more units. If rents were capped to be affordable at 80 percent of AMI, the corresponding number of Inclusionary Conversion units would be between 2,500 and 2,900, depending on the minimum building size.

Under the modeled policy choices, the greatest number of units would be created in Wards 1 and 2, and especially Ward 3. This outcome is driven by the location of rent-controlled apartment buildings and their prevailing rents. For example, it does not appear that a significant number of units would be converted in Wards 5, 7, and 8 if the affordability target were set at 80 percent of Area Median Income, because most units already rent below this threshold; Wards 4 and 6 similarly do not generate a large number of Inclusionary Conversion units because they have few rent-controlled buildings, even though they have higher prevailing rents. Even with a deeper affordability target set at 50 percent of Area Median Income, Wards 4 and 6 would produce an estimated 300 units each; Ward 5, an estimated 150 units; Ward 7, 120 units; and Ward 8, approximately 100 units.

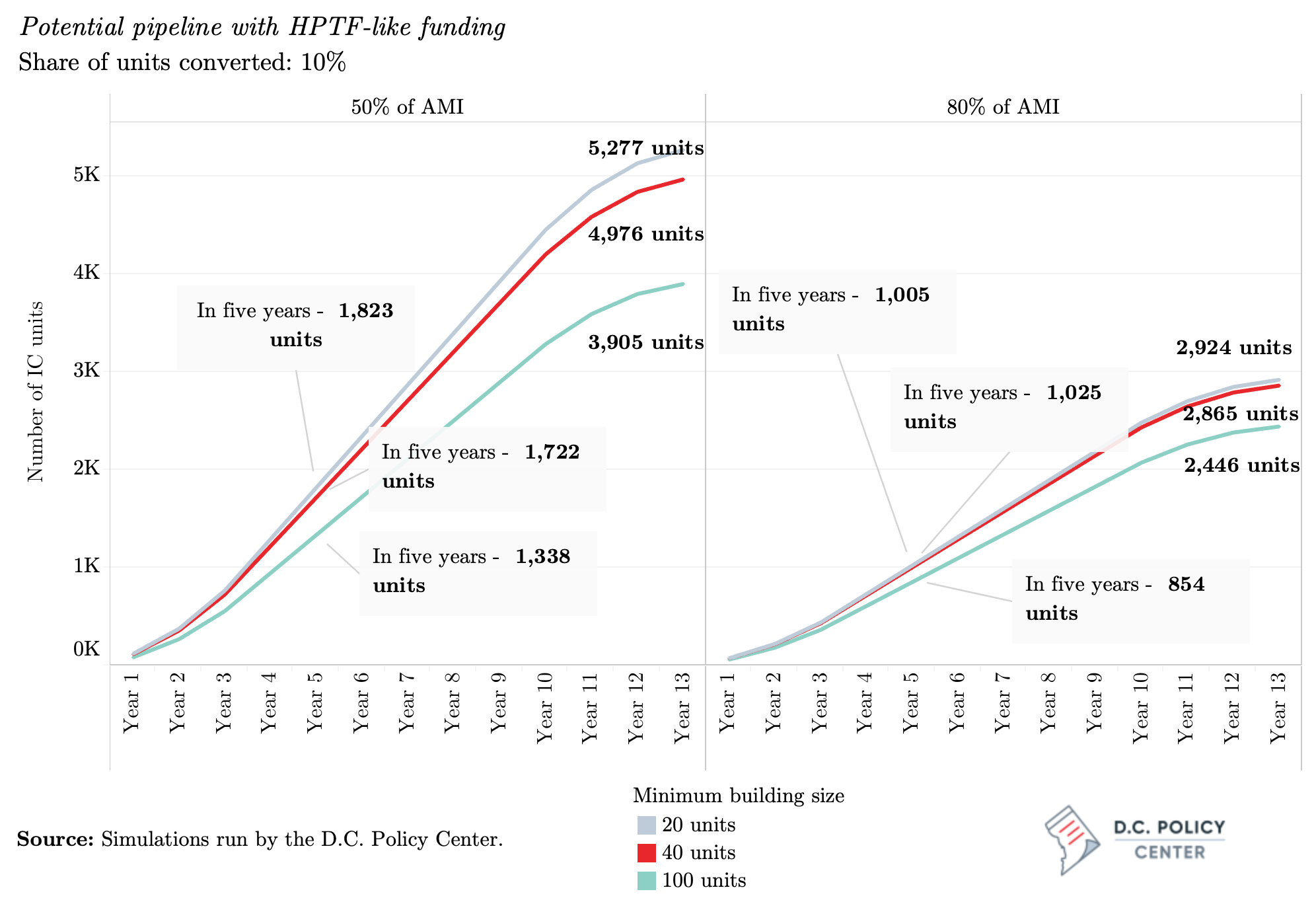

Not all these units will come online at the time of program implementation. If the District implements the conversions at the time of a refinancing event, with a HPTF-like loan, conversions will happen over time, as each building goes through its refinancing cycle. The landlord decision to refinance is sensitive to the business cycle and interest rates, and reliable estimates are not available for how many units go through refinancing every year. The presence of a voluntary agreement could also be a trigger.[3] Based on conversations with industry leaders, this analysis uses the assumption that buildings go through refinancing about every 10 years. This means the Inclusionary Conversion program will begin with modest numbers, will reach about 30 percent of its potential by its fifth year, and will likely reach full potential in 13 years.

Even if the city implements the program at once, immediately converting the units in return for an annual subsidy, only about 30 percent of the Inclusionary Conversion units would likely be immediately available through existing vacancies. In this case, the program can reach its full potential over approximately 11 years if about 10 percent of the units turn over each year.

The reach of the program could be expanded by extending it to cover all rental apartment buildings constructed before 2007, when the District implemented its inclusionary Zoning program. But as shown earlier, little construction took place between 1975 and 1999 (approximately 7,000 units, some of which are already publicly subsidized affordable units). Such an expansion will likely add about 600 more units at a 10 percent conversion rate.

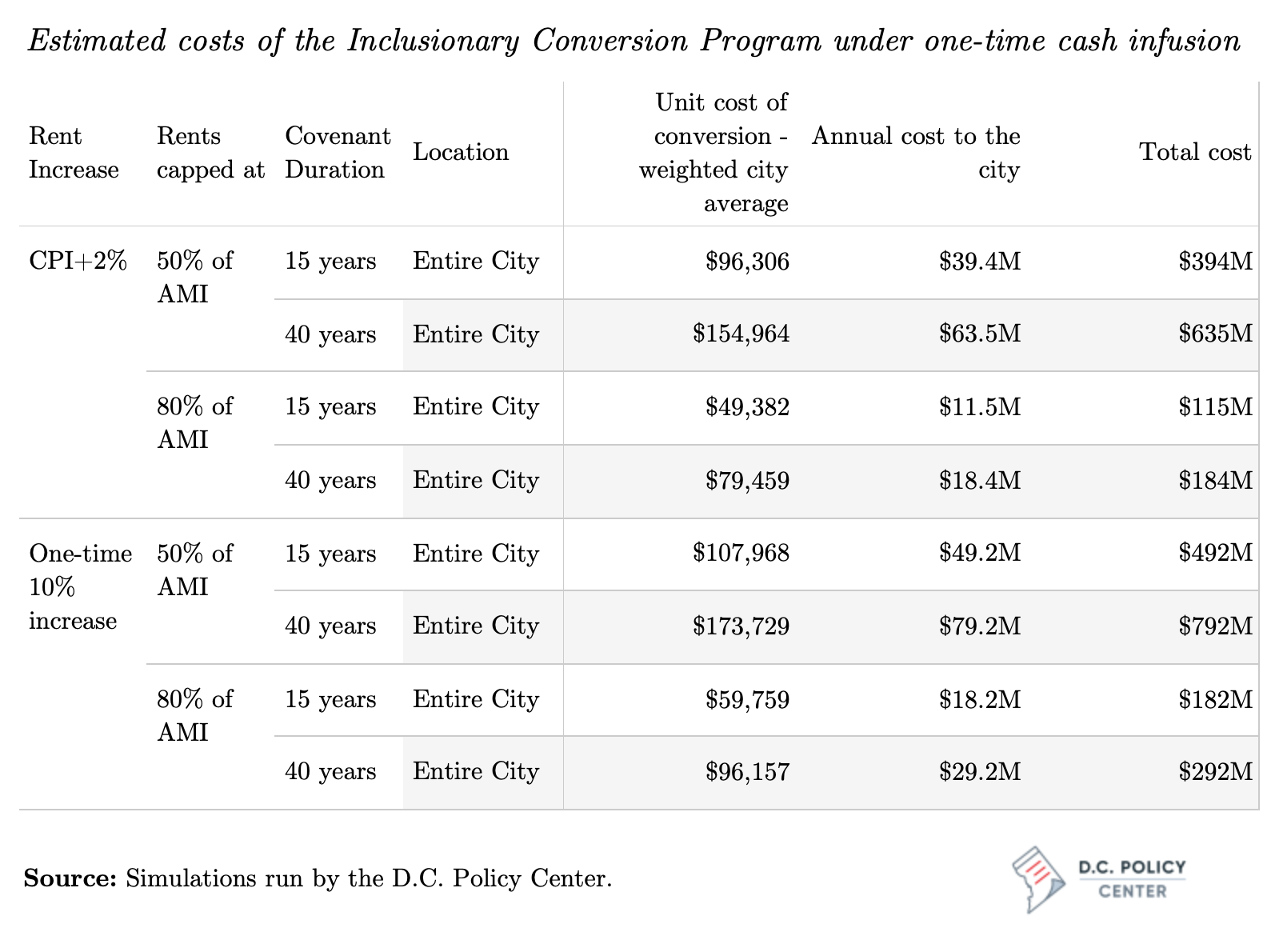

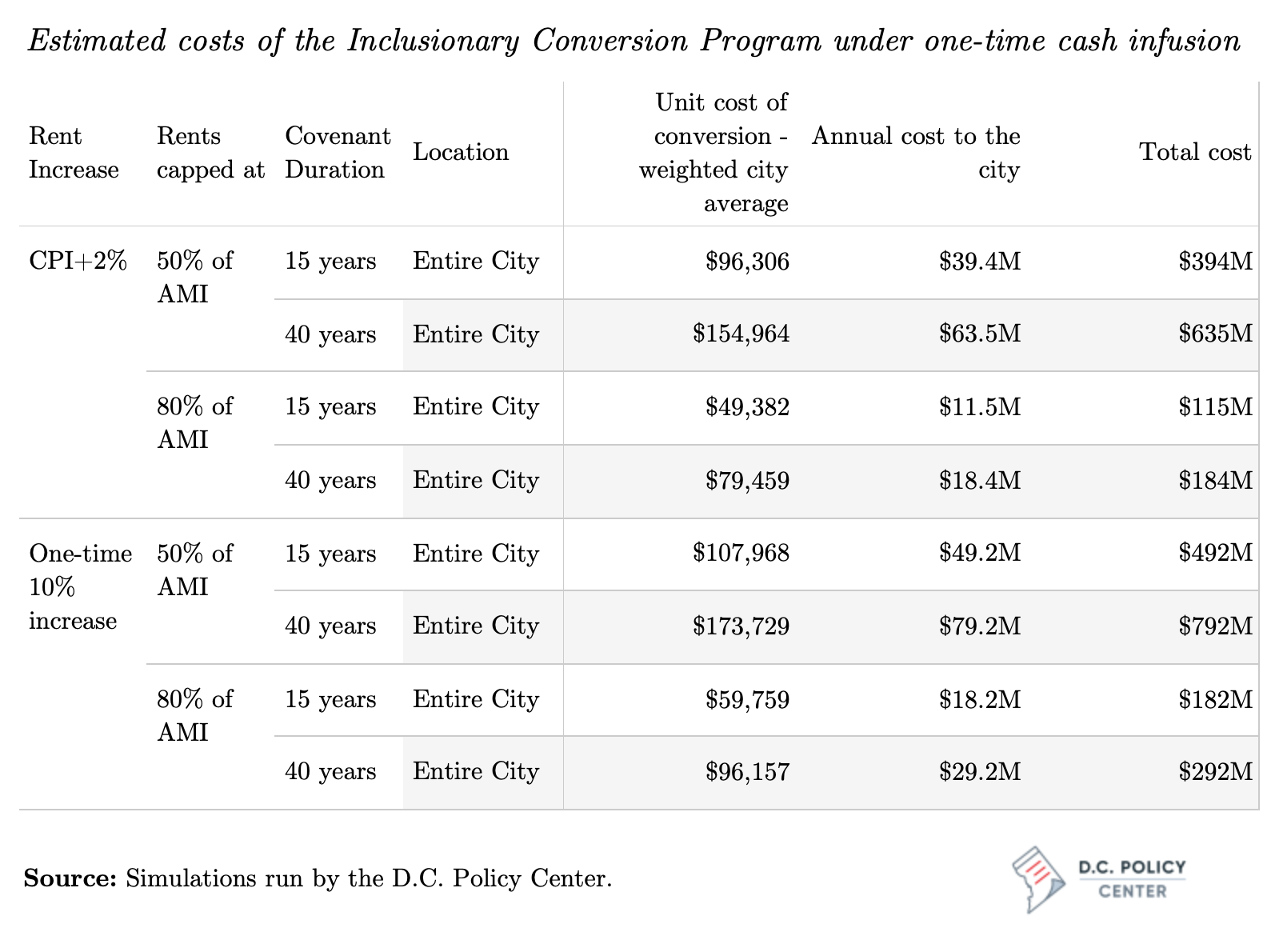

Estimated costs

The costs of adopting the Inclusionary Conversion program will depend on several variables, some dictated by policy design, and some by the market. Any policy choice that reduces the rent threshold (thereby creating affordable housing for lower-income households) or increases the duration of covenants will increase costs.

The city would also incur the costs differently if Inclusionary Conversions are treated like HPTF-type projects with a one-time cash infusion compared to an approach where they are funded by an annual subsidy similar to the project-based local rent supplement. In the first case, the costs would be most sensitive to the cap rates and would be incurred immediately at the time of conversions. In the latter the costs would continue through the life of the covenants and they would presumably be most sensitive to changes in the CPI.

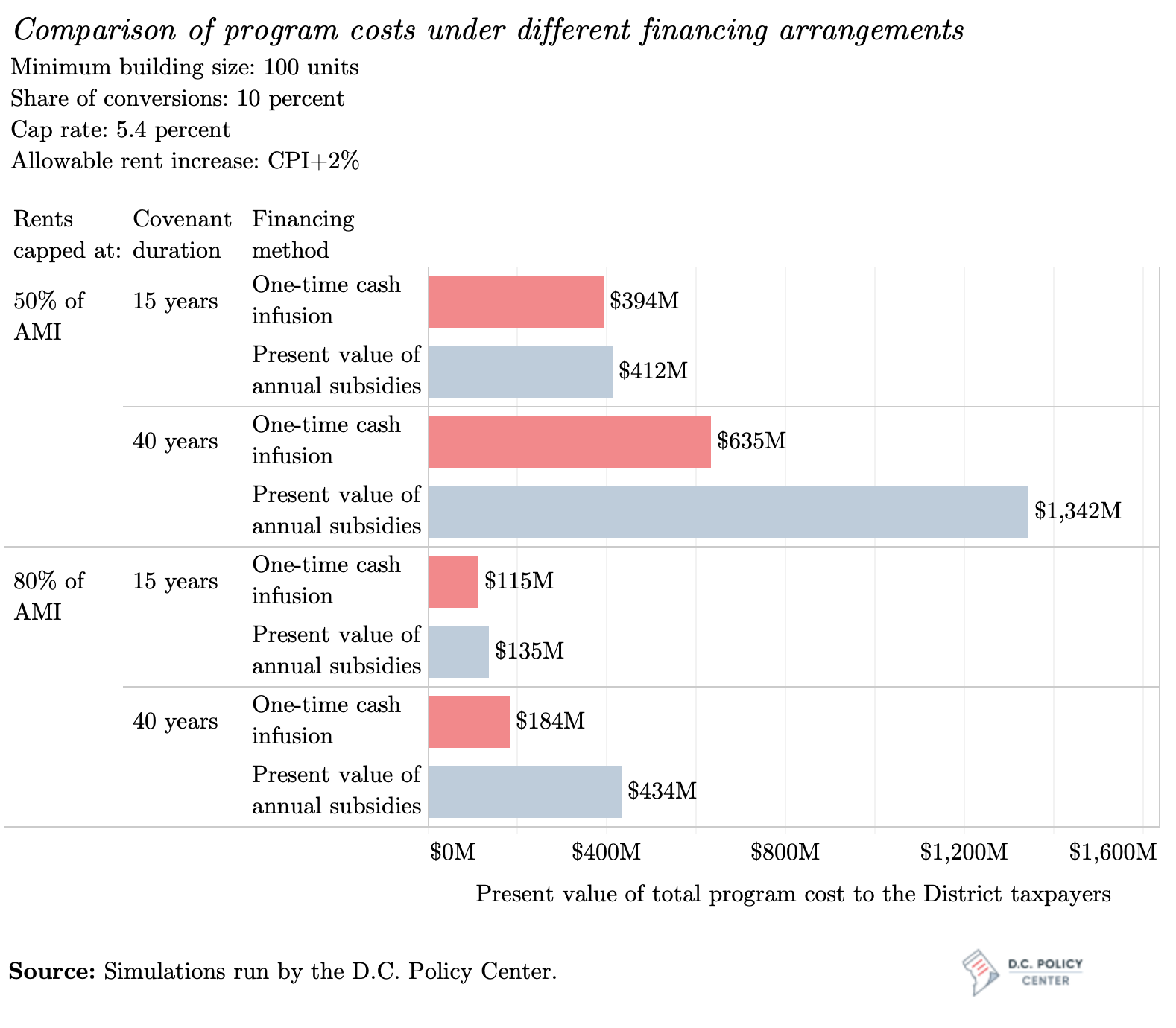

Costs under one-time cash infusion approach

Modeling the one-time cash infusion approach offers a sense of how the per-unit cost of conversion will compare to the per-unit costs of production and preservation under current HPTF programs. To illustrate the potential costs under a one-time cash infusion, the report models the following assumptions and program choices:

- The cap rate is assumed to be 5.4 percent. This rate is chosen because it is the average cap rate across all multi-family buildings according to CoStar. This is lower than the cap rate than the Office of the Chief Financial Officer’s baseline cap rates for Class B and Class C buildings, regardless of their location,[4] and therefore brings a level of conservativeness to the model.[5]

- Two different policy choices for covenant durations. In one scenario, the model uses 40 years—the current required duration for rental properties receiving HPTF loans. In the second, the model uses 15 years as the approximate duration of borrowing for rental properties.

- Two different affordability targets. As before, the model considers a scenario where rents are capped at 50 percent of AMI, and another scenario where rents are capped at 80 percent of AMI.

- Two different rent profiles after refinancing: The first scenario modelled is one where rents increase at CPI+2%, which is what is currently allowable under D.C.’s rent control laws. The second models a 10 percent one-time increase in rents to show how costs could change if the landlord enters into a voluntary agreement or is seeking a temporary exemption to meet a critical capital investment or maintenance need.

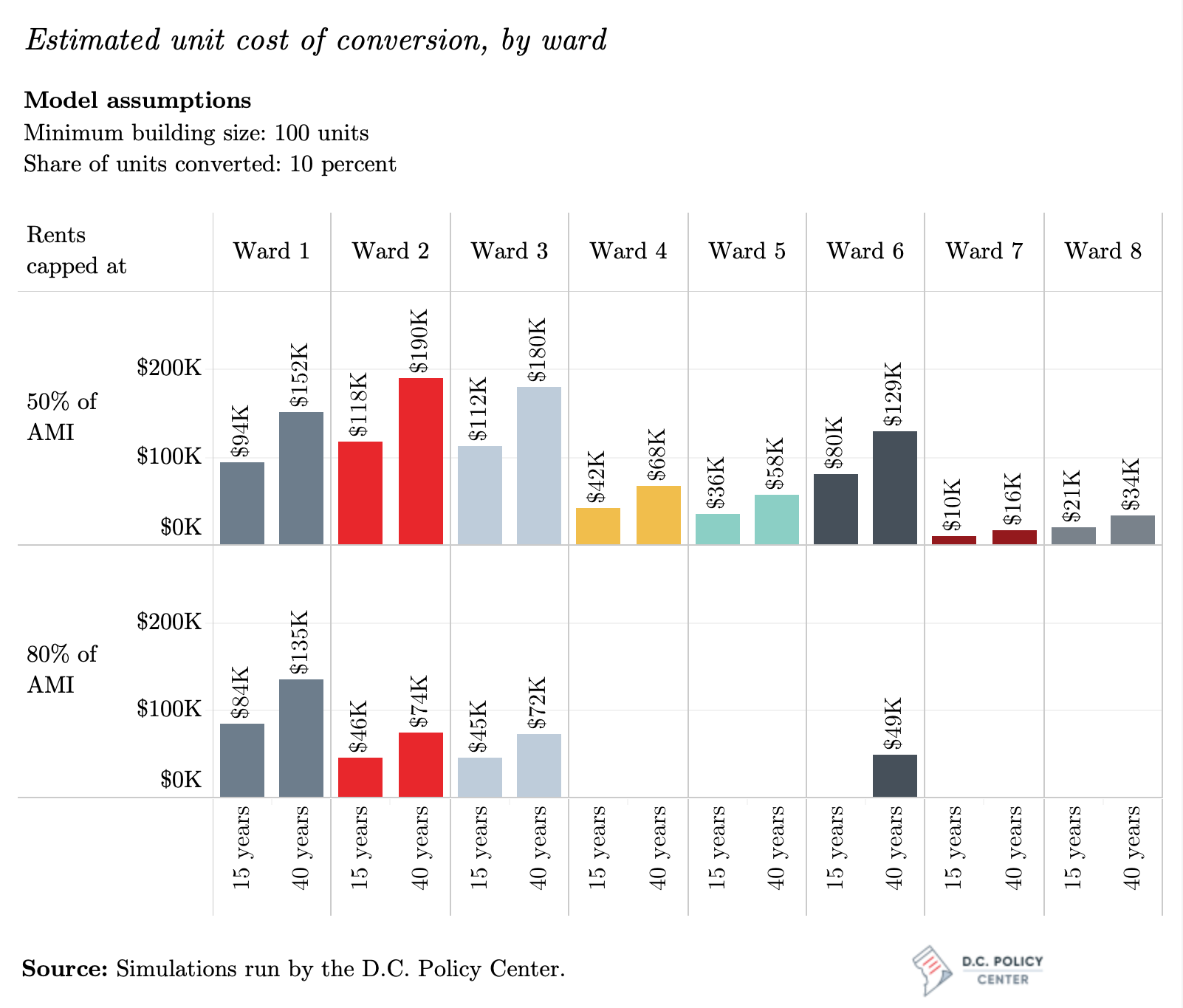

- For purposes of this example, findings are only presented for buildings with 100 or more units to illustrate how costs vary by different affordability targets and the duration of the covenants.

These estimates suggest that creating one Inclusionary Conversion unit with rents capped at levels affordable at 50 percent of Area Median Income would require a one-time subsidy of $96,000 for a 15-year covenant and $155,000 for a 40-year covenant (Figure 35). At an affordability target of 80 percent of Area Median Income, the corresponding unit costs are lower, at $49,400 and $79,500 per conversion. These are averages across the city weighted by where the units are likely to be created (Wards 1, 2, and 3, where rents are relatively higher). If the city were to impose all inclusionary conversion requirements on all rent-controlled buildings, it would have to spend between $63.5 million per year (for broader coverage and deeper affordability) to $11.5 million per year (for narrower coverage and shallower affordability) for 10 years.

In the simulations presented, the two scenarios most similar to existing HPTF programs are those with 40-year covenants that do not allow for rent increases (similar to HPTF refinancing supports), and those with one-time rent increases (most comparable to HPTF substantial rehabilitation loans.) The estimated citywide cost of conversion under these scenarios are $155,000 and $174,000 per unit when rents are capped at 50 percent of Area Median Income. And while these seem high compared to the average cost of units to HPTF under its current mix of projects, this is largely because the Inclusionary Conversion program creates units where it has been too costly to produce affordable units through the production and preservation programs supported by the HPTF. Also, the simulation simply caps all rents at 50 percent—a deeper affordability target than what the HPTF currently produces.[6]

The estimated unit cost for conversions in Wards 2 and 3 under a 40-year covenant where rents are capped at 50 percent of Area Median Income are $190,000 and $180,000 respectively . While not small, these are not unusual numbers as far as subsidies go for deeply affordable units. And they are well below the amount necessary to build from scratch such units in Wards 2 and 3, even if it is assumed that there is room under current zoning to build them. Similar costs for Wards 7 and 8 are $35,000 and $23,000 respectively for the longest covenants and the most liberal rent-increase assumptions.

These analyses show that Inclusionary Conversions can be transformative for the city’s affordable housing supply, especially if it focused on providing deep affordability as modelled with the rents capped at 50 percent of Area Median Income, but which could also be a mix of affordability targets similar to the requirements of the HPTF. All parts of the District will see an increase in affordable housing, but the impacts would be greatest in Wards 1, 2, and 3, with costs that can be contained.

Costs under operating subsidies

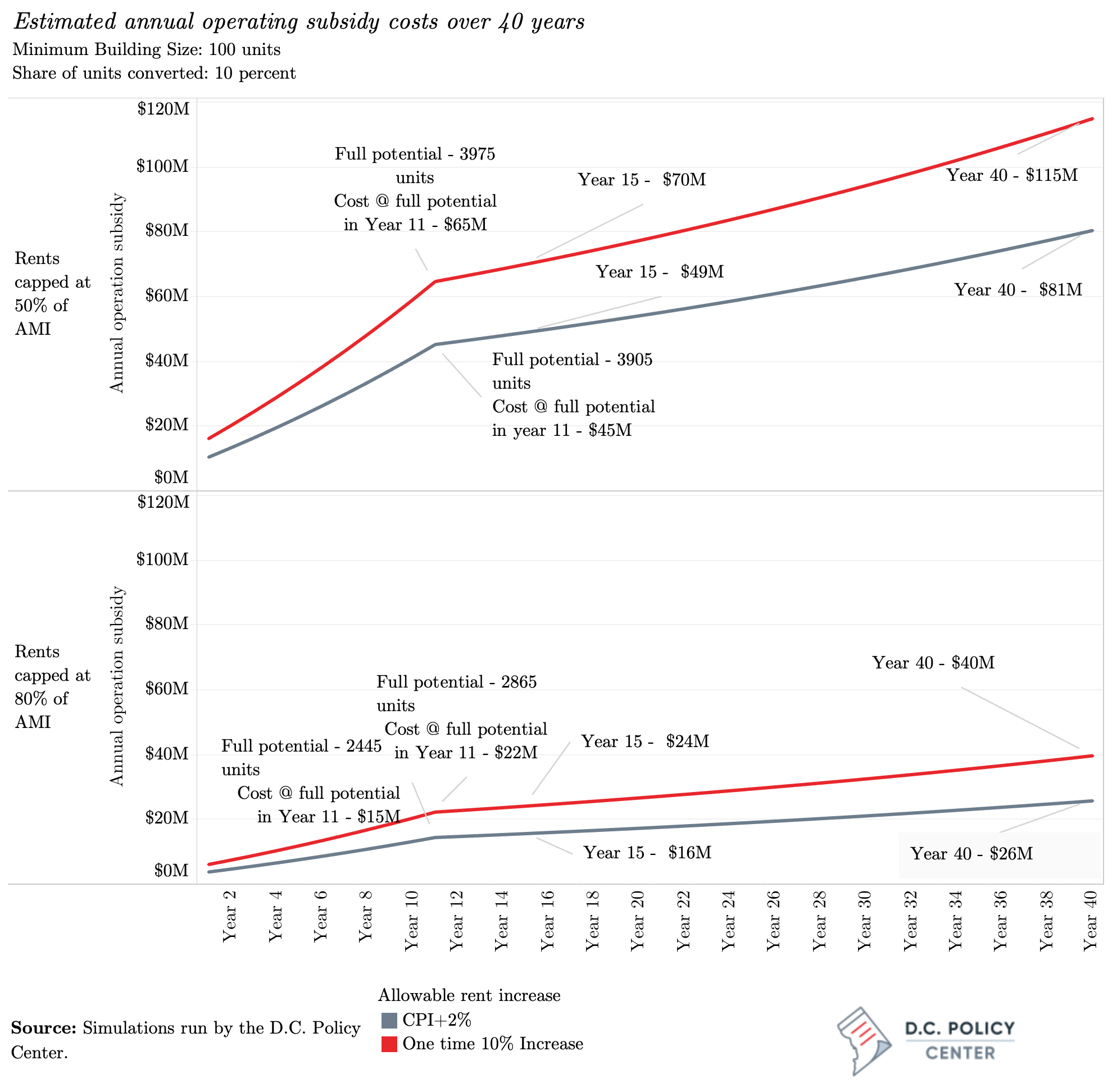

If the District government were to pay for the Inclusionary Conversion program through an annual operating subsidy similar to project-based Local Rent Supplements, the city would commit to a series of payments, potentially increasing at CPI+2% over the duration of the covenants.

Under this scenario, units would be gradually converted through turnover, so costs would increase faster until when conversions are completed (year 11 in the presented pipeline). At this time, the required annual subsidy would be an estimated $45 million to $65 million if rents were capped at 50 percent of Area Median Income, and an estimated $15 million to $22 million if the rents were capped at 80 percent of Area Median Income, adjusted for inflation and allowable rent growth.

After the program reaches its full potential, the annual subsidy will only grow by CPI+2%.[7] Because the Inclusionary Conversion program would be funded by an annual subsidy, the duration of the covenants would not change the required public expenditure per year; it would, however, affect the period over which the District would commit to make such payments.

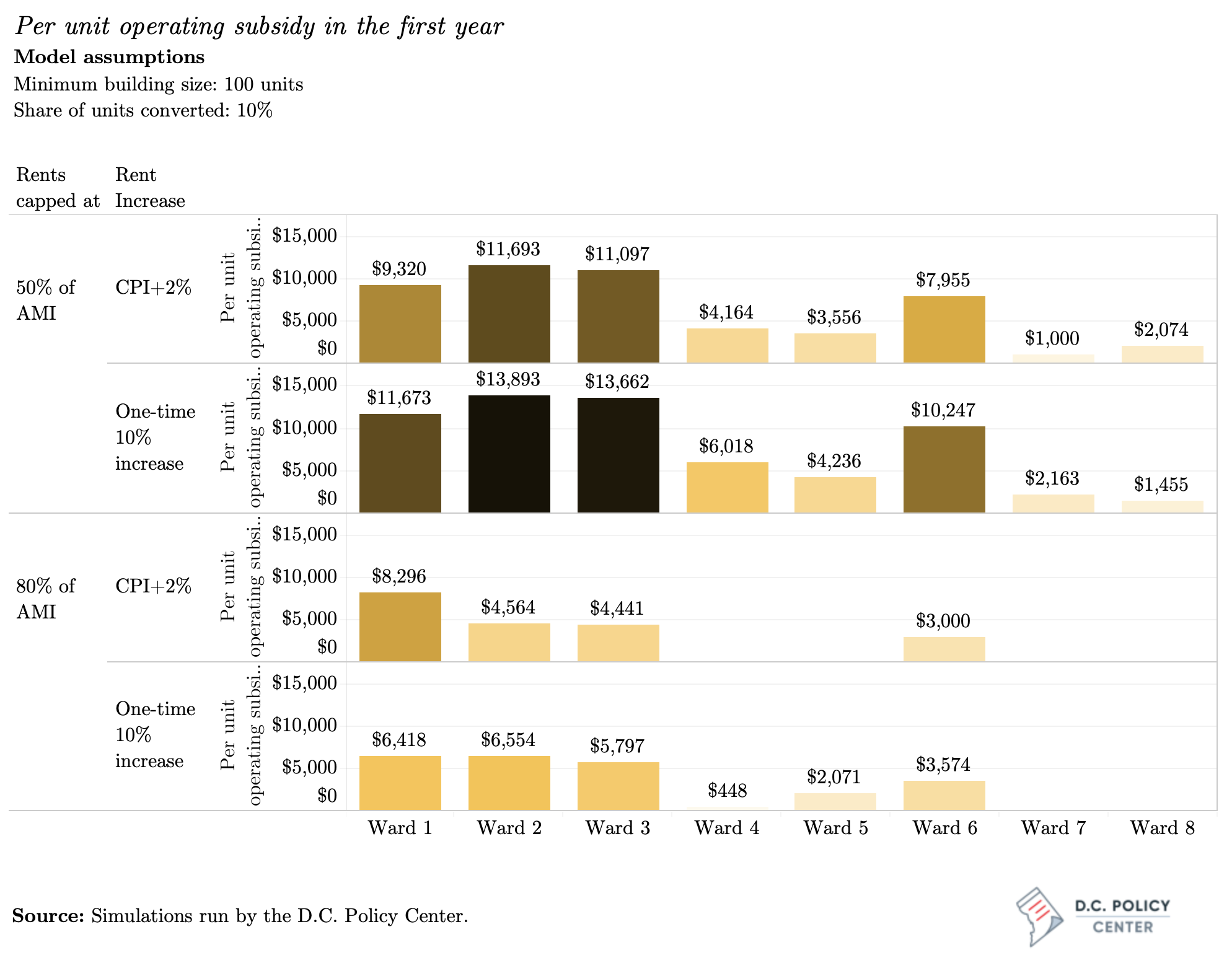

The per-unit operating subsidy necessary to support Inclusionary Conversions could also compare favorably to the subsidies available from the federal Section 8 multi-family program and the District’s own local rent supplement program. The annual subsidy per unit is estimated to be $9,500 across the entire city if rents are capped at 50 percent of Area Median Income, and $4,500 if capped at 80 percent of the Area Median Income. These costs would be higher for parts of the city where rents are high. Comparison of these subsidies to the federal Section 8 tenant-based voucher program and the District’s own Local Rent Supplement Program are not perfect (voucher amounts are driven multiple eligibility criterion for the households), but instructive. [8] For example, in the Cleveland Park tax assessment neighborhood in Ward 3, the DC Housing Authority, which administers these vouchers, sets the rent limit at $2,467 for a unit with one bedroom (excluding utilities).[9] For a family of two earning 80 percent of the Area Median Income ($77,640), the maximum available annual subsidy cannot exceed $6,324, regardless of the actual rent for the unit. [10] This is an amount greater than the amount estimated under the Inclusionary Conversion program, which targets affordability at same income level ($4,441).

Using tax abatements to pay for affordability

So far, this report has described the costs of an Inclusionary Conversion program as an annual subsidy that can be incorporated into the District’s operating budget. The city can also offer landlords a tax abatement in return for a commitment to capping the rents at certain affordability levels. To be sure, whether paid for by a tax expenditure or an operating expenditure, the program’s fiscal impact on the city would be the same. However, examining the necessary tax reductions that can support the Inclusionary Conversion program can still be instructive as it highlights that rent-controlled buildings have significantly different rent structures. and a policy that offers the same level of subsidy to all buildings would help some buildings more than the others.

Based on this analysis, if the city pursues an affordability target of 50 percent of Area Median Income, it can likely pay for the annual subsidies by reducing the real property tax rate from the current $0.85 per $100 value to $0.31 per $100 value. However, these rates are averaged across all eligible buildings that are contributing units; there are some buildings in the sample where the subsidy amount is too high relative to the tax obligation, and even a full tax abatement could not pay for a 10 percent conversion requirement. These buildings have relatively lower values, reflecting the variations in other characteristics—such as building age, location, and state of its repair—that impacts its tax assessment. In fact, a full tax abatement can support a slightly lower number of units than a 10-percent conversion rate.

Comparing the two financing models of one-time cash infusion and annual operating subsidies

There are advantages and disadvantages attached to the two financing approaches (a one-time cash infusion and an annual operating subsidy). Perhaps the biggest difference is in costs, especially for longer-term covenants. In every scenario explored in this analysis, the one-time cash infusion has a lower cost measured in today’s dollars when compared to the present value of annual operating subsidies: It is $20 million less expensive when rents are capped to create affordability at 80 percent of Area Median Income with 15-year covenants, and $710 million less expensive for 40-year covenants at 50 percent of Area Median income.

The main reason for the diverging costs under these two different financing approaches is the discount rate that drives the calculation of present-day value of the two benefits. Under a one-time subsidy, the future income the landlord is forgoing is discounted by the cap rate, which takes into consideration both the potential income growth and risks in the real estate market. In the latter, the discount rate is the statutory cap on rent increases.

The simulations presented here use a 5.4 percent cap rate to discount the future incomes of rent-controlled buildings. This, it turns out, is a greater discount rate than the CPI+2%, hence producing lower present values. But this raises an important question about how to think of allowable rent increases under a rent-control model. CPI+2% is only indirectly related to the conditions in the real estate market. CPI is backward-looking, as it is based on the increase in the cost of living (including housing costs) in the previous year, whereas cap rates are forward-looking, incorporating the expected changes in demand and supply and the potential risks and opportunities in the real estate market. As a result, the CPI+2% rule will sometimes underestimate and sometimes overestimate the rent growth the market would support. That the present value of the subsidy is greater under the CPI+2% rule suggests that, at least for now, it is overestimating what the market can bear. And if the District ties its subsidies to this rate, it runs the risk of paying too much (or too little) compared to the required subsidy.

There are, however, other salient differences between these two financing approaches:

- Conversion risk. Under the annual subsidy approach, the landlord receives the subsidy only after the unit is converted. The city does not assume any risk if tenant turnover is slower than anticipated. Under the one-time cash infusion approach, the landlord receives the subsidy up-front, and city bears the risk of slower tenant turnover that would reduce the pace of conversions. This risk is greater when the required share of conversions is higher and could be minimized if the share of conversions is kept under 7 percent of all units, which is the current vacancy rate across all rent-controlled buildings.

- Structural impact on rental housing. That cap rate itself is also sensitive to policy: by simply adopting inclusionary conversions, the city could impact the cap rates. The most obvious reason would be the commitment to a lower rent over a long period of time could depress building values. Other variables in the model could have similar structural impacts: for example, if the conversion rates are high, they could change the income profiles of tenants (and therefore the revenue profile of the building) significantly altering its value.

- Maintenance risk. Under the annual subsidy approach, the subsidy can motivate the landlord to keep the building in good repair. Under a one-time cash infusion approach, the District commits to refinancing up front, and is susceptible to landlord negligence, especially under the 40-year covenant version when the city would rely on the landlords’ good faith to keep the units in good repair over a long period of time. (This is also a consideration with current HPTF funding.) While under both approaches, the city would need to invest substantially in compliance, under an annual subsidy model, the consequence of poor maintenance can be immediately addressed by withholding the subsidy.

- Fiscal impact. Under the annual subsidy approach, the city makes a long-term financial commitment with rapidly increasing costs that could not be fully recognized in its budget and financial plan, which only extends to four years. Under the one-time cash infusion approach, because the subsidy for each cohort is one-time and is not recurring (unlike an operating subsidy, such as a voucher or a tax exemption), its fiscal impacts are contained and certain.

Extensions to the model

The Inclusionary Conversion model could be extended to ensure that a certain number of units are delivered each year, or the number of units are maximized for a given amount of funding. Such extensions are briefly discussed below:

- Cap and trade. The baseline model with one-time financing reflects a mechanism design with a DOPA-like structure where the conversion process begins with a notification from the landlord about the landlord’s intention to refinance. But the city does not need to wait for the natural occurrences of refinancing: Under this alternative program design, the District would set ward-level targets for the creation of Inclusionary Conversion units, and then issue a request for proposals. The city can then choose the lowest bidder so long as ward-level targets are being met. In this way, the share of units would be allowed to fluctuate across buildings, shifting funding to those where the unit cost of conversion is lowest. To ensure that each building has a certain mix of rents, the number of eligible units in a building can be capped.

- Additional support for major rehabilitation. The baseline model does not assume that the District provides additional support for major rehabilitation for buildings with limited revenues and therefore limited ability to borrow. It only assumes that the infusion from the District would be equal to the present value of rent subsidies to keep the units affordable over the period of covenants. The District can provide additional financial support in return for more Inclusionary Conversion units, especially if the building is in extensive disrepair and would need more of a cash infusion at the time of closing to make the refinancing possible.

- Weights attached to unit sizes or rehabilitation characteristics. The District can incentivize, for example, two-bedroom units over smaller units by attaching a preference for conversion of these larger units. Similarly, the District can create a preference for types of rehabilitations in line with the District’s environmental goals.

Implementation concerns

While the goal of this report is not to provide detailed recommendations on how the program could be implemented, it may be useful to describe some implementation concerns the city would have to consider to ensure that the Inclusionary Conversion tool can serve as intended: reducing housing burdens for lower-income District residents while creating economic inclusion across the entire city:

- Who will administer the program and verify incomes? An important decision regarding the implementation of Inclusionary Conversions is program administration. At present, income verification for some housing programs are done by the Department of Housing and Community Development; for some, by the District of Columbia Housing Authority; and for some, it is left to landlords. Under the Inclusionary Zoning program, landlords are required to re-verify income every 12 months, and prospective tenants participate in a lottery when a unit turns over. In contrast, income verification is done by the District of Columbia Housing Authority for the Housing Choice Vouchers. For the Inclusionary Conversion program, a central office that provides income verification and serves as a triage for directing tenants to buildings would likely serve the program best. In this way, current voucher or rent supplement recipients who are placed in an Inclusionary Conversion unit would no longer require a subsidy (or would require a smaller one), allowing the District to divert these resources to other tenants in need of housing support.

- How will eligibility be allowed to change from year to year? Household incomes can change over time, and households that enter an affordability housing program may no longer meet the requirements for that program in later years. This means the city must decide whether income eligibility is checked periodically, and whether the eligibility test would make some allowances in income growth beyond the affordable rent growth. If these rules are too strict, tenant turnover could increase considerably; if they are too weak, then the benefits would be less targeted over time. Under the current Inclusionary Zoning rules, for example, tenants who lose their eligibility must move out, although it unclear how these rules are enforced.

- How will units that already meet Inclusionary Conversion requirements be included into the program? Some units in rent-controlled buildings could have tenants that already earn below the affordability target. As noted in Section Four, an estimated 7 percent of renters in the District have moved into their units sometime before 2000, and a smaller percent could have moved even earlier in 1970s and 1980s. These tenants could often be retired or close to retirement and would possibly become income-eligible for an Inclusionary Conversion unit. And if these tenants have occupied their unit for a long period of time, their rents could already be at or close to the rent cap under the affordability requirements. The District must therefore decide whether these units would be counted as Inclusionary Conversion units (and begin receiving subsidies). Providing subsidies for these units mean locking their affordability in for longer periods of time, ensuring that these tenants can stay in place. The same concerns would be true for rent-controlled buildings in parts of the city where the rents are already low.

- How will the District ensure that landlords maintain their buildings through the duration of covenants? This is a concern for current HPTF projects with 40-year covenants as well. It appears that those projects fully expect to refinance using additional supports from the HPTF when their units age sufficiently to require major maintenance. This means there are truly no projects that are fully supported for what is needed to commit to a 40-year covenant.

- Caps for affordable units. In order to ensure that no building loses its mix of incomes for residents (where higher rents from higher-income tenants help subsidize lower rents for lower-income residents), the city could consider capping the number or share of units that can participate in an affordability program.

It is also important to note that none of the implementation issued explored above would be unique to the Inclusionary Conversion tool. All housing programs must balance allocating public subsidies where they are needed the most with ensuring that tenants are not facing uncertainties because of eligibility rules. All housing programs must provide an incentive for the landlord to participate. And all housing programs must invest significantly in compliance. Similar constraints inevitably exist for Inclusionary Conversions.

You’ve reached the end of Chapter 5.

<< Back: Chapter 4 | Next: Chapter 6 >>

Or return to the main publication page.

Notes

[1] The Area Median Income for a single-person household is $84,900. At 60 percent of the Area Median Income, the maximum rent is (84,900 0.6 0.3)/12 = $1,274.

[2] The cap rate is derived by dividing the property’s net operating income by its market value. The higher the operating income relative to the market value, the higher the cap rate, thus signaling a higher discount rate for future revenue from the building. Theoretically, each building has a different cap rate reflecting the various risk associated with investing in it: its age, location, and status, type, tenants’ solvency, term or structure of tenant leases, as well as overall market conditions. The cap rate is also affected by systemic risk such as deterioration in macroeconomic fundamentals. The District’s real property tax assessors use a city-wide cap rate (adjusted for location and characteristics of buildings) to estimate market assessment for an income-generating property like a rental apartment building. To do so, they use the same formula: divide the net operating income (obtained from the landlord) by what they think the appropriate cap rate is for the building.

[3] As shown in the Appendix, this number has ranged between 10 and 20 buildings each year. However, no information is available on the number of units covered by these agreements.

[4] The OCFO’s Reference Materials for Appraisers suggest that the lowest cap rate for Class B buildings is 5.5 percent, and the highest cap rate is 6.6 percent. These rates vary by location. For Class C properties, the comparable cap rates are 5.8 percent and 7.2 percent. This information is available on page 7 of the Tax Year 2020 Pertinent Data Book For The District Of Columbia.

[5] The model presented in this report is capable of estimating costs at different cap rates. We find that each 10-basis point change in the cap rates change the costs to the D.C. government by about 1 percent.

[6] When researchers run the model with an affordability distribution that replicates the current HPTF production, the comparable unit costs decline to $108,000 for straight conversions and $136,000 for projects with a major rehabilitation. To replicate the HPTF production, researchers ran the model with rents capped at 30 percent of AMI for 20 percent of the units, capped at 50 percent for 30 percent of the units, at 60 percent for another 30 percent of units, and at 80 percent of AMI for the remaining 20 percent of the units.

[7] In the chart, the estimated annual subsidy is growing by 2 percent only.

[8] Voucher limits are set under the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Small Area Fair Market Rent guidelines and show that the subsidy amounts could be higher than what we estimate to be necessary for the Inclusionary Conversion approach.

[9] Available here. We thank Luke Lanciano for the pointer.

[10] I.e., the difference between 30 percent of the household income ($23,280) and the annual housing expenditure under the Fair Market Rent ($2,467 x 12 = $29,604).