In April, President Biden set a national greenhouse gas emissions reduction target of 50-52 percent of 2005 emissions levels by 2030. Meeting this goal will require the U.S. electricity sector to source 80 percent of its generation from carbon-free energy sources by 2030, with President Biden setting a further target of 100 percent of U.S. electricity generation to be sourced from clean energy sources by 2035.

Nationally, the electricity sector will need to rapidly adopt renewable energy and retire fossil fuel generators (especially coal) in the next decade to source the majority of its electricity from renewable sources. According to a major study on a 2030 U.S. clean energy grid, the nation will need to entirely phase out coal by 2030 and adopt 120 gigawatts (GW) of new wind and solar capacity every year to meet Biden’s emissions target.1 That rate is approximately 3.5 times what the entire U.S. electric industry built in renewable capacity in 2020, and about 50 percent of total currently installed national renewable capacity. Despite the challenges, wind and solar have become comparatively affordable, rapidly becoming one of the most cost-effective means of electricity generation, meaning that the U.S. could maintain current electricity prices after transitioning to clean energy, even with large increases in electricity demand.

Today, roughly 40 percent of electricity generation comes from clean energy sources nationally – approximately 20 percent from renewables and about 20 percent from nuclear. Regionally, many states have set their own carbon emissions and clean electricity generation targets (called Renewable Portfolio Standards or RPS). Washington D.C. has a RPS target of 100 percent of the District’s electricity generation being sourced from clean sources by 2032, the most aggressive 100 percent clean energy target of any state.

While D.C. has aggressive clean energy targets which put it on track to meet these goals, D.C. generates nearly none of its own power and will rely primarily on solar renewable credits to meet its targets. This article will examine how the broader Mid-Atlantic region is currently projected to change its electricity market in the coming decades, how its energy transition is progressing, and how it compares to the rest of the nation.

The Mid-Atlantic’s current electricity market

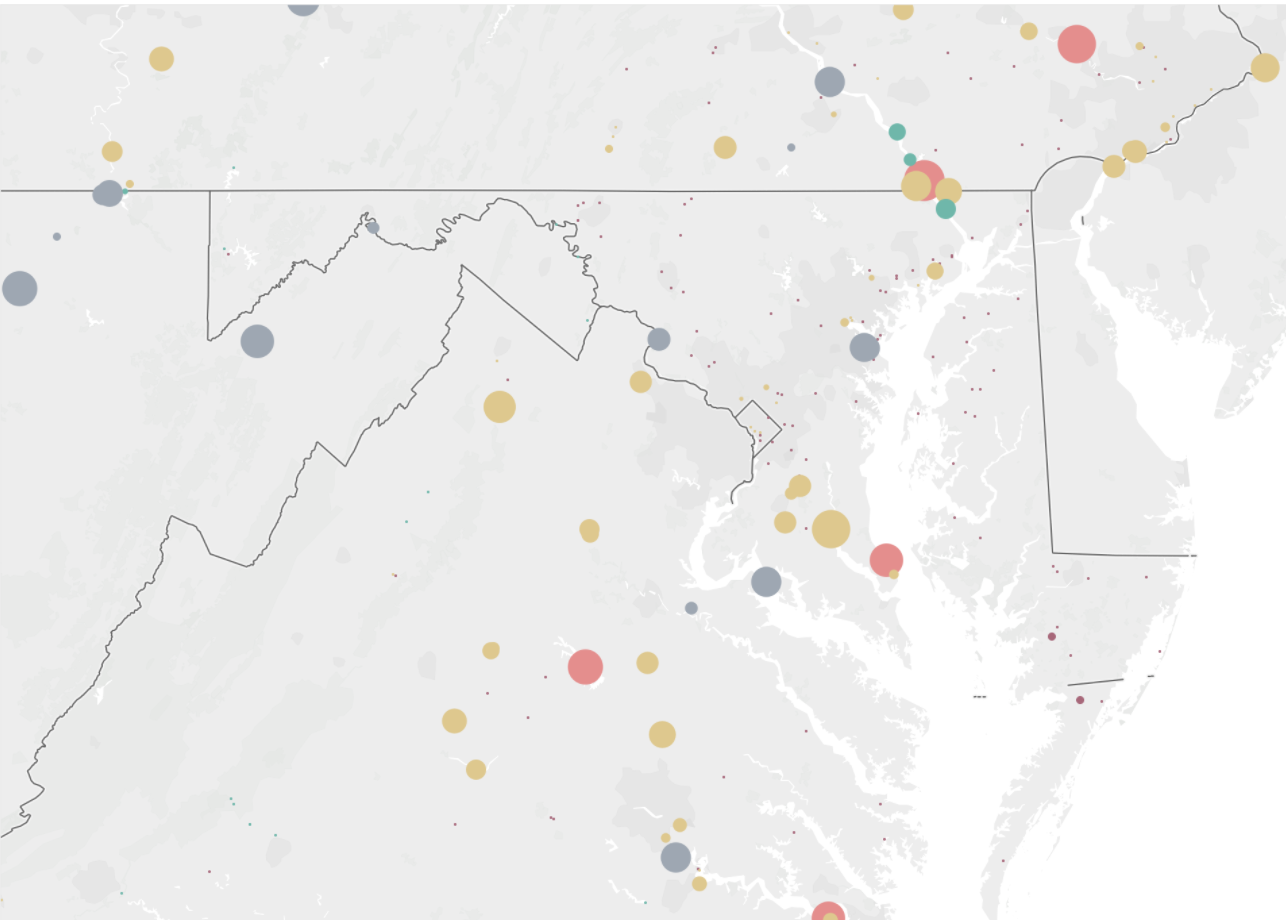

Most of the Mid-Atlantic is part of the PJM (named for Pennsylvania-New Jersey-Maryland, but which also includes parts of Virginia, West Virginia, Delaware, Illinois, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Kentucky, and North Carolina) regional transmission operator (RTO), who manages dispatch of individual generators and ensures regions are meeting demand for power.

Projected change in PJM regional electricity generation

With over half of the PJM region’s electricity coming from non-renewable sources, primarily gas and coal, meeting national clean energy targets will be a challenge. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) projects that the eastern part of PJM (Virginia, Maryland, D.C., and some of Pennsylvania and NJ) will produce only 20 percent of its electricity from renewable sources by 2040, falling far short of the national 2030 80 percent clean energy target. Meeting national clean energy targets will require big changes in policy and additional renewable energy sources.

Currently, 7 percent of eastern PJM’s electricity comes from renewable sources, with another 30 percent coming from nuclear (D.C. has a larger share of its electricity from nuclear than the region as a whole), putting the region’s clean energy sources at 50 percent of total demand. EIA projected that increases to clean energy will come mostly from increasing power from solar and offshore wind, growing regional renewable capacity by over 30 GW by 2040. To put these numbers into perspective, Virginia alone will need to add 47 GW of solar and wind capacity by 2030 to meet the 80 percent clean energy target.

Part of the eastern PJM region’s challenge is that while it has reasonable solar generation potential, it does not have as much generation potential for onshore wind as the West and Midwest regions which have strong winds around the plains. Regional offshore wind potential, however, is very good, and some analyses suggest offshore wind alone could power many eastern states. As such, the Biden administration plans to install large new offshore wind farms across the eastern seaboard.2

With the EIA currently forecasting increases of only a few gigawatts a year in solar and offshore wind capacity additions, regional utilities would need to greatly accelerate renewable development to meet, or even come remotely close to, national emissions targets. Utilities will also need to retire dozens of gigawatts of coal capacity ahead of schedule, as well as some gas. Coal emits more than double the carbon emissions of natural gas, making its retirement the most crucial move toward reducing emissions in the future. Current forecasted retirements come primarily from coal and oil, with most of the region’s generation expected to derive from gas by 2030 (and even 2040).

How the Mid-Atlantic compares to other regions in the nation

The Mid-Atlantic overall ranks lower in forecasted electricity generation from clean energy sources when compared to other U.S. regions. New England, New York, the West, and Texas are all are projected to have a higher percentage of electricity generation sourced from clean sources by 2040 than the Mid-Atlantic, with only the South and Midwest lagging behind. The Mid-Atlantic’s clean energy generation as a share of total electricity generation is forecasted to rise just 0.7% per year, well below regions like New England (1.5%/year), New York (1.1%/year), and the South (1.2%/year).3

Part of why the Mid-Atlantic is lagging behind other regions in the country in renewable energy production is its reliance on coal. PJM, covering most of the Mid-Atlantic region, is projected to have the highest amount of coal capacity of any region in just two years. Reaching an 80 percent clean grid nationally by 2030 would require almost all of this to be retired in just nine years, a task likely insurmountable without immediate policy action. A national clean electricity standard is one of the most popular related proposals, one that would force utilities to alter their resource planning to meet clean energy targets.

D.C. city efforts toward increasing renewable energy

While the District does not produce the majority of its energy and thus has limited control over its source, D.C. contributes to clean energy goals by purchasing renewable credits. Over half of the District’s energy is currently produced by non-renewable sources, mainly gas and coal. Notably, the highest percentage of the District’s energy comes from nuclear energy, making up approximately 36 percent of D.C.’s total generation. This percentage is significantly higher than the national average (20 percent) and is the main source of the city’s clean energy capacity.

D.C. has two methods for achieving its 2032 renewable standard goals: purchasing solar renewable energy credits (SRECs) from solar power producers (in or out of D.C.) and generating its own solar power. D.C. hopes to meet its renewable energy goals largely by requiring D.C.s electricity suppliers4 (mainly PEPCO) to purchase SRECs from solar producers in the PJM region. D.C. is requiring SREC purchases to increase each year until the city is purchasing 95% of its annual electric demand in these credits. While D.C. has very little open land for generating its own power, these credits provide cash to solar operators largely outside the city, encouraging the market to develop more solar power to make up for the city’s electricity use. Electricity suppliers for D.C. have been meeting these intermediate goals.

D.C. aims to generate 5% of its annual electricity demand by solar in the city by 2032. So far, the city has fallen only narrowly short of its annual incremental targets to keep the city on track for this 2032 target. To help meet the city’s solar generation targets, D.C. has generous solar programs for residents that have helped increase solar adoption in recent years. While total energy produced by solar remains low (3.2 percent of total energy), city certified installed solar systems increased 39% between 2019 and 2020 alone, bringing hope for the future.

The city’s solar efforts are extremely important, with solar expected to generate most of D.C., Maryland, and Virginia’s electricity in a fully clean-grid. States further north like Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York, will likely rely more heavily on wind.

However, transitioning to a clean energy grid is no simple task. To meet emissions targets laid out by the Biden Administration, the electric grid will not only have to meet current demand, but potentially must foster dramatic increases in electric vehicle adoption and the electrification of heating and cooling in buildings – leading to considerable increases in electricity demand. PJM (D.C.’s regional grid operator) projects large increases in distributed solar (rooftop solar on homes or at small businesses) will help keep total projected load and peak growth low (PJM peak electricity demand is only projected to grow 0.3% per year with D.C.’s PEPCO peak expected to decline 1.2% per year).

Climate change requires changes to the electricity grid

Climate change will continue to cause large strains on the electricity grid across the nation. With severe weather causing large outages this past February in Texas, outages last year in California, and nearly this year again in California, severe weather poses a significant risk to electricity markets. D.C. is particularly susceptible to hurricanes and cold weather storms, which put its grid at further risk. These wildfires and storms add to the importance of new transmission lines, batteries, weatherization of generators, and other mitigation strategies.

Transitioning to a grid that can weather large climate change induced storms and maintain reliability year-round will require large investments. Princeton estimates that setting the nation on a course for a net-zero future would cost a starting investment from 2021-2030 of about $2.5 trillion, much of it in transmission capacity, efficient buildings, electric vehicles, and other investments outside of building new renewable power units. Energy Innovation projects Virginia alone would need to invest $59 billion in wind, battery, and solar capacity, not including any investment in transmission capacity or efficient buildings.

However, the benefits drastically outweigh the cost. Princeton’s study cites the benefits of reducing air pollution alone could top $1 trillion. Other benefits include creating millions of clean energy jobs, potential reductions in energy prices (as renewables require no fuel costs), and improving health, while reducing the U.S.’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Conclusion

While the region and much of the nation has a difficult challenge ahead to meet climate targets, the goal is well worth the effort.

Policymakers, consumers, and especially utilities will have to get serious about setting strict climate goals. Virginia’s Dominion Energy is already leaning more heavily on adding offshore wind, extending nuclear licenses, retiring coal, and adding solar capacity after the state passed a tougher renewable portfolio standard. It also recognizes that wind and solar have become the comparatively cheapest option for future capacity additions.

Aggressive federal and state targets, mixed with continuing falling costs for solar and wind and an increasing push for early retirements of coal plants, will all help utilities rapidly scale up their transition to clean energy.

As most of the country watches climate change induced weather cause wildfires burning the west, giving us the most severe storm seasons in history and scorching record heatwaves, the urgency for a transition to clean energy couldn’t be more serious.

Additional resources on clean energy

- UC Berkeley’s 90% Clean Grid by 2035

- Princeton’s Net Zero America

- A National Roadmap for Grid-Interactive Efficient Buildings

Endnotes

- (for reference, the Hoover Dam, one of the largest dams in the country, is only 2 GW of capacity)

- Offshore wind remains more expensive (although significantly cheaper than it once was) than onshore wind and often has higher regulatory burdens to begin construction, which is why so little of it has been constructed in the U.S. previously.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration 2021 Annual Energy Outlook.

- The D.C. metro area is served primarily by two utilities, Dominion Energy (or Virginia Electric), and PEPCO.