Understanding the District of Columbia’s criminal justice system is imperative as D.C. works toward racial equity, statehood, and criminal justice reform. D.C.’s criminal justice system is administered mainly by the federal government—a direct result of the Revitalization Act. This makes D.C.’s system uniquely complicated, and has far-reaching impacts on D.C. residents.

What does the history of D.C.’s criminal justice system look like, and what changes were enacted under the Revitalization Act? This introduction to the District’s criminal justice system outlines its current structure, analyzes how Revitalization Act changes have impacted justice system operations, and evaluates outcomes for D.C. residents.

About this series

This publication is part of the D.C. Policy Center’s Criminal Justice Week 2023, which explores various aspects of the District’s criminal justice system. Other publications in this series include:

- Processing through D.C.’s criminal justice system: Agencies, roles, and jurisdiction

- A look at who is in D.C.’s criminal justice system

- How much would it cost to build and maintain a new D.C. prison?

- Chart of the week: Where are D.C. Code offenders housed today?

These publications are adapted from The District of Columbia’s Criminal Justice System under the Revitalization Act: How the system works, how it has changed, and how the changes impact the District of Columbia, commissioned by the District’s Criminal Justice Coordinating Council.

The Revitalization Act: Born of a need for fiscal relief

In the mid 1990s, the District of Columbia government had reached an untenable financial situation. In the wake of a recession,1 declining population, and a weakening tax base, coupled with poor financial management, the city could no longer pay for its expenses. The District faced challenges including crumbling infrastructure, a high Medicaid cost burden,2 a $5 billion unfunded pension liability it took over from the federal government with Home Rule in 1974,3 and high spending needs driven by the District’s obligation to provide both state and local level functions under a restricted revenue capacity.

By 1995, the District’s operating deficit had reached $722 million (18 percent of its projected spending that year),4 but with its bond ratings dropped to “junk” levels, the city was unable to borrow to manage cash flow, meet spending needs, or invest in infrastructure.5

Infrastructure needs were particularly dire across the District’s criminal justice system. For example, overcrowding6 and decrepit living conditions at the District’s Lorton Correctional Complex resulted in several large-scale riots throughout the 1980s and 1990s, including one incident in which 14 buildings were set on fire.7 Additionally, the city’s court buildings were in dire need of infrastructure investments for which it had no means to pay.

With the District repeatedly spending more than its approved budget, in 1995 Congress passed legislation instituting a Financial Control Board to oversee the District’s finances.8 However, the city’s challenges were too big to be solved purely through financial management. To provide needed financial relief, Congress also enacted the National Capital Revitalization and Self-Government Improvement Act of 1997—commonly referred to as the Revitalization Act—on August 5, 1997.

How the Revitalization Act changed D.C.’s criminal justice system

D.C.’s early criminal justice system

In the District’s early history, the jail and parole functions of the city’s criminal justice system operated under local control. The first D.C. Jail was built in 1872, and was later combined with the Lorton Correctional Complex, alongside the creation of the D.C. Department of Corrections in 1946. The current D.C. Jail has also been also under local control from the start, beginning with the opening of the D.C. Central Detention Facility (CDF) in 1976.9 Similarly, the D.C. Board of Parole was created in 1932 and oversaw all D.C. parole decisions and supervision of people on parole until the Revitalization Act of 1997.

In contrast, the court system experienced multiple changes regarding structure and jurisdiction, often combining federal and local jurisdiction. Between 1801, when the first local court was created, and 1970, when the current system of local court jurisdiction was set in the District, courts were recreated or transformed into other forms by the federal government at least ten times. In this period, courts oversaw federal cases as well as local D.C. cases, with local court jurisdiction falling first to Circuit Court between 1801 and 1863, and then to Superior Court between 1863 and 1970. By 1970, Congress established two separate courts for the District of Columbia: the D.C. Superior Court (DCSC) and the D.C. Court of Appeals (DCCA).10 This court structure remains in place today.

Photo: Original D.C. Jail, built in 1882 and replaced in 1976. Credit: StreetsofWashington of Flickr. (Source) CC BY-NC 2.0.

Timeline of D.C. criminal justice agency creation, 1801 – 1995

1801: Circuit Court created, including Justices of the Peace and Orphans Court. D.C. local jurisdiction is under the Circuit Court.

1802: The original charter of Washington was approved. The city was granted centralized police authority, the power to establish patrols and impose fines, and the power to establish inspection and licensing procedures. The D.C. police had only an auxiliary watch with one captain and 15 policemen until the establishment of a formal police force in 1861.11

1838: Criminal Court created.

1861: The Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) was created, with an authorized force of 10 sergeants, up to 150 patrolmen, and up to 10 precincts.

1863: President Lincoln abolishes the Circuit Court because of perceived Southern loyalties of the sitting judges. Supreme Court of the District of Columbia is created. The new court had four judges selected based on political loyalties to the United States. Local jurisdiction switches to D.C. Supreme Court.

1870: Police Court created in 1891 (shares jurisdiction with D.C. Supreme Court).

1872: The first D.C. jail is built.12

1893: Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia created. This court was later renamed the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in 1943.

1906: Juvenile Court created.

1909: Municipal Court created.

1910: Lorton Correctional Complex opened, including the Lorton Reformatory, originally named the District of Columbia Workhouse. Over the years, Lorton inmates constructed a railroad (1910), farmed cows and chickens and turkeys (1940s to 1960s), and the prison even served as a missile site for the US Army (1950s to 1970s).13

1912: A women’s workhouse was added to Lorton.

1932: The D.C. Parole Board is created.14

1935: A juvenile facility and maximum security penitentiary were both added to Lorton.

1936: D.C. Supreme Court becomes the District Court for the United States.

1937: Tax Court is created.

1942: Municipal Court and Police Court become Municipal Court for the District of Columbia, The Municipal Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia becomes the Intermediary Court for D.C.

1946: The DC Department of Corrections (DOC) is established as an agency. DOC combines the first D.C. Jail (established 1872) with the Lorton Correctional Complex (established 1910).15

1948: U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia becomes a fully federal court alongside the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.

1962: The Municipal Court of Appeals becomes the District of Columbia Court of Appeals. Municipal Court becomes the D.C. Court of General Sessions.

1963: Pretrial Services Agency was created with a Ford Foundation grant. It became an official agency under the Executive Office of the Mayor with the passage of the Bail Agency Act in 1967. It was later renamed the D.C. Pretrial Services Agency in 1978, and then Pretrial Services Agency for the District of Columbia in 2012.16

1970: Congress establishes separate courts for the District of Columbia: the D.C. Superior Court (DCSC) and the D.C. Court of Appeals (DCCA).18 The Home Rule Act provided for an elected Mayor and a 13-member Council, delegating certain powers to the new government.19 However, this new D.C. government was prohibited from taxing federal property and nonresident income.20 Congress also retained legislative veto power over Council actions through passive oversight and required active approval of the District’s budget as a part of the federal appropriations process.21

1976: The Central Detention Facility opens, located in southeast D.C.

1987: New guidelines for the D.C. Parole Board go into effect, which were later clarified in 1991.

1992: The Correctional Treatment Facility opens in D.C.22

Changes to D.C.’s criminal justice system wrought by the Revitalization Act

The Revitalization Act included numerous federal supports and interventions to help D.C. gain its fiscal footing. The local Medicaid match requirement was reduced from 50 percent to 25 percent (although this was done in an annual appropriations bill, not in the Revitalization Act), and the federal government provided the District with the authority to borrow from the Federal Treasury to finance $400 to $500 million in debt because the city’s bond ratings had foreclosed any opportunity to borrow from markets. In return, the city gave up an annual federal payment of $660 million.

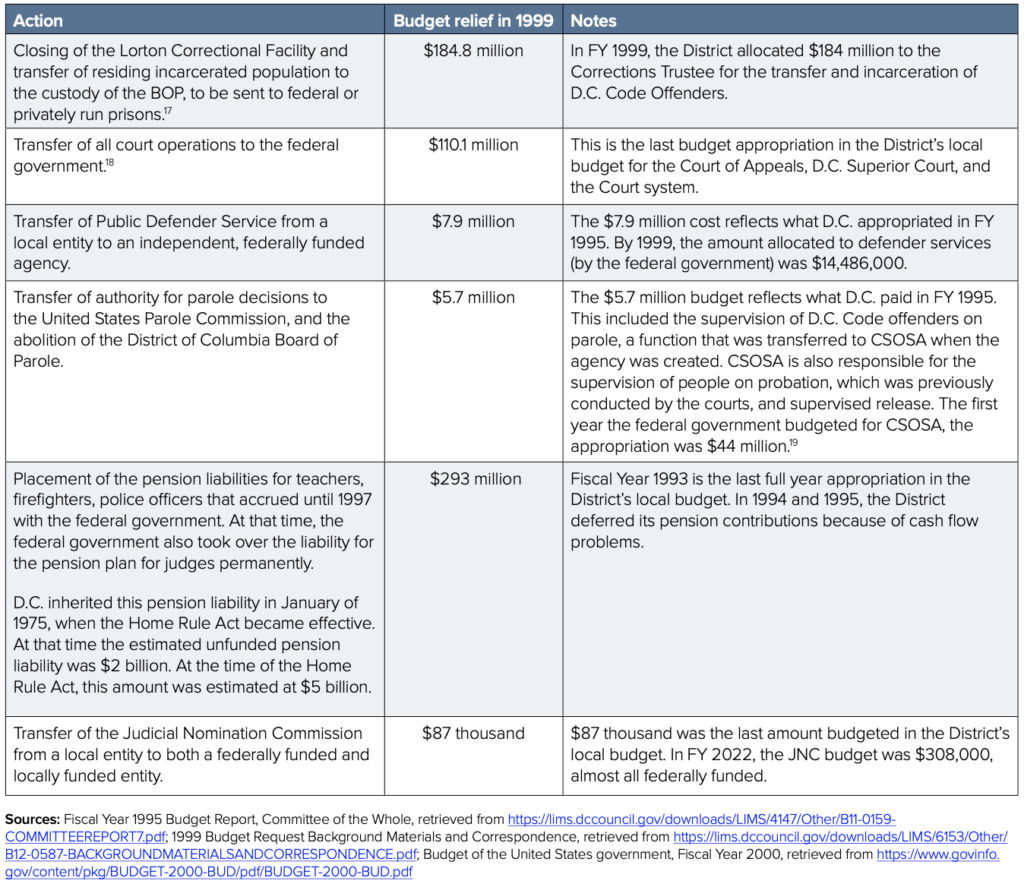

The Revitalization Act also fundamentally altered the District’s criminal justice system. The federal government agreed to overtake various financial and managerial obligations including the D.C. courts, the prison system and the custody of incarcerated persons, and all pension liability accumulated through 1997. The federal government also assumed fiscal responsibility for pre-trial, trial, incarceration, parole, and supervision responsibilities, relieving the District from fiscal obligations that accounted for an estimated 11 percent of the city’s operating budget in 1998.

With federal takeover of many of the functions, The Revitalization Act fundamentally altered the District’s criminal justice system. These changes included:

- Closing the District’s Lorton Correctional Complex and transferring custody of D.C. Code offenders with sentences over a year to the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP);

- Abolishing the D.C. Board of Parole and transferring decision-making authority over parole matters to the U.S. Parole Commission (USPC);

- Reassigning pretrial and post-conviction community supervision responsibilities from the courts to the Pretrial Services Agency (PSA) and the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA);

- Taking over the financial responsibility for the operations of the District of Columbia Court System, including the D.C. Superior Court and the D.C. Court of Appeals;

- Classifying the District’s Public Defender Service (PDS) as a federally funded entity; and

- Establishing the Truth in Sentencing Commission (which later became the District of Columbia Sentencing Commission).

What the Revitalization Act means for analyzing D.C.’s criminal justice system today: Benefits and challenges

Approximately 25 years after the Revitalization Act, few people fully understand the scope and operations of the District’s current criminal justice system, and little analysis has been done on how the system operates as a whole and how it serves the District’s residents.

Importantly, while some parts of the criminal justice system are extremely well-resourced with federal funding that provides significant fiscal benefits to the District of Columbia, information about how the system functions and resident outcomes are often publicly unavailable and difficult to assess.

Further, it is difficult to determine what the District’s criminal justice system would have looked like if all its components were under local control. We simply do not know the counterfactual path of fiscal and institutional decisions. Likewise, it is difficult to compare the District’s criminal justice system to systems in other jurisdictions on matters including funding, operations, and demographics of the District’s incarcerated population.

In terms of individual experience with the criminal justice system, it may be more appropriate to compare D.C. to other cities, given the District’s urban nature. But from a systems and funding perspective, it is more appropriate to compare the District to states and localities combined, since the District is both a state and local government and has both the revenue raising capacity and expenditure obligations of both a state and a local government.

The federalization of D.C.’s criminal justice system makes comparison even more difficult, since it means that that federal funding of many of District’s agencies do not appear on the District’s budget books, and many agencies operate under federal guidelines or in federal systems. Overall, the District benefitted financially from the Revitalization Act, but not all federal systems are set up to best serve D.C. residents involved in the criminal justice system.

Publicly available information is insufficient to develop a clear picture of institutional practices and decision-making processes. The lack of a repository of practices that shape the system may be linked to the intricate system of criminal justice agencies created by the Revitalization Act. The District’s criminal justice system is made up of federal, local, and independent entities sometimes funded by federal sources, sometimes funded by the District of Columbia government (and sometimes both). Entities that make up the system report to different authorities, and therefore may have different priorities. This means there is no single (or consistent) goal or performance target. This made it difficult to paint a full picture that tracks outcomes across the entire system.

There were significant fiscal benefits from the federal takeover of various components of the criminal justice system—as intended by the Revitalization Act.

At the time of its implementation, the District was relieved of criminal justice system related expenditures, which made up approximately 11 percent of the city’s operating budget. Further, today, federally funded entities receive budgets that are much higher than the inflation-adjusted budgets (i.e. adjusted for today’s prices) they received from the D.C. government the last time they received local funds, as well as the federal budgets they received at the time of the transfer. That is, not only the District is not having to pay for these operating expenses, but the federally funded components of the criminal justice system are also much better resourced than they were when under District control.

Table 1. Fiscal relief from the Revitalization Act in Fiscal Year 1999

Some elements of the current system may have resulted in negative outcomes for the District of Columbia.

Because the District is not in charge of its criminal justice system, some components of the system may not be set up to best serve District residents. These include:

High vacancies in courts and slow appointment of judges: While the current system imposes a timeline for the President to appoint a judge when there is vacancy in D.C. Courts, there is no timeline over which the Senate must hold a confirmation vote. This is the process for all Senate confirmations, not just for D.C. judges, but it has led to increased vacancies since there is little political pressure District voters can use to press the Senate for timely confirmation actions. While this issue is tied to the Home Rule Act of 1973 and not the Revitalization Act of 1997, the issue persists and has been exacerbated by the backlog of cases created by the COVID-19 pandemic.

A prison system that may have contributed to reduced success upon reentry. D.C. Code offenders are only a small portion of the population under BOP custody, and they are housed in prisons that are far away from their families or communities. The Revitalization Act did not require BOP to place D.C. Code offenders in a particular facility or provide a particular type of environment. While it is BOP policy to place offenders within 500 miles of their home, when possible, over 45 percent of D.C. Code offenders are held more than 500 miles from D.C., which can result in cut ties with community, family, and result in disruption of services such as health care. While no publicly available data exists that systematically tracks how D.C. Code offenders have been treated and what types of rehabilitation activities they participate in, other research shows that D.C. Code offenders typically do not participate in educational programming and are sometimes placed in high-security prisons that do not offer rehabilitation or educational programs.

A parole system that is not transparent. There is surprisingly little public information in the outcomes of parole hearings and whether USPC makes timely decisions to reduce the amount of time served after eligibility for parole or supervision. However, data suggest that a lower percentage of D.C. Code offenders have been released on parole under USPC jurisdiction than under the jurisdiction of D.C.’s parole board.

These changes in jurisdiction have significantly changed how people in D.C. experience the criminal justice system, funding levels, and how decisions are made about the system as a whole. The federalization of D.C.’s criminal justice system has significant impacts on the experience and outcomes for D.C. Code offenders, more information for which can be found in the main text of our report.

Endnotes

- The 1990-91 recession was one of the shortest and mildest recessions in the U.S. history. The recession lasted for 8 months from June 1990 to March 1991, but employment did not recover until 1992.

- The high spending in Medicaid was due to two factors. First, while the District’s median income was higher than the fifty states, concentrated poverty meant a large share of residents were eligible for Medicaid. Second, because of the high median income, the District had to match 50 percent of all Medicaid expenditures—the highest match rate possible under the federal formula.

- Prior to Home Rule in 1974, all D.C. government employees were technically federal government employees eligible for pension. When D.C. received Home Rule, these employees were reclassified as D.C. government employees, and city became liable for their pension benefits, which was estimated to be $2 billion and was entirely accumulated by the federal government. Over the next twenty years, this unfunded pension liability grew to $5 billion.

- General Accounting Office (1995), “District of Columbia Financial Crises, Statement of John W. Hill, Jr. Before the Subcommittee on the District of Columbia, Committee on Appropriations, and the Subcommittee on the District of Columbia, Committee on Government Reform and Oversight, House of Representatives.”

- Bouker, J. (2008). Appendix 1 – The D.C. Revitalization Act: History, Provisions and Promises.

- By 1995, Lorton had around 7,300 inmates, or 44 percent more than intended for that facility.

- “Prison Set Ablaze During Riot.” (1986). Chicago Tribune.

- District of Columbia Financial Responsibility and Management Assistance Act of 1995, Pub. L. 104-8 (1995).

- “About DOC.“ DOC.

- “History of the DC courts.” District of Columbia Courts.

- Brief history of the MPDC. Brief History of the MPDC. (n.d.). Retrieved July 11, 2022, from https://mpdc.dc.gov/ node/226472

- DOC, “About DOC.”

- Tang, J. (2020). “Here’s a fascinating story about the old Lorton, Virginia prison.”

- Browning, S. (2016). Three Ring Circus: How Three Iterations of D.C. Parole Policy Have up to Tripled the Intended Sentence for D.C. Code Offenders. Georgetown Journal of Law & Public Policy, 14(2), 577- 598.

- DOC, “About DOC.”

- “PSA’s History and Role in the Criminal Justice System,” Pretrial Services Agency.

- “History of the DC courts.” District of Columbia Courts. Wheeler, ”No escaping the history of Lorton Prison.”/note] Local jurisdiction switches to DCSC and DCCA.

1972: D.C. Parole Board publishes its first set of parole guidelines. Previously governing rule came from the D.C. Code.

1973: Congress passed the D.C. Self-Government and Governmental Reorganization Act (Home Rule Act), granting the city limited local control.17Pub. L. No. 93-198, 87 Stat. 774 (enacted December 24, 1973).

- Currently, the only elected governance body in the District was the School Board, which has its own contentious history with the federal government. Just like governance over the city, governance over schools frequently shifted between elected and appointed boards over the District’s history. In 1968, the Congress adopted legislation (Public Law 90-202) to create a fully elected school board with 11 members.

- It was also prohibited from changing the Federal building height limitation, altering the court system or changing the criminal code until 1977.

- In a 1983 decision, the Supreme Court invalidated one-house legislative vetoes in INS v. Chadha (Supreme Court of the United States, INS v. Chadha, 462 US 919. That decision required Congress to modify the procedure for ordinary District legislation and for amendments to the District Charter. Congress decided to make amendments proposed by the District presumptively valid, unless Congress enacted and the President signed a joint resolution of disapproval. In so doing, Congress left in place the narrow limitations on the District’s Charter amendment authority.

- DOC, “Correctional facilities.”