This week, in celebration of Sunshine Week and as stipulated in D.C.’s Data Policy, the Chief Data Officer released the first Enterprise Dataset Inventory. The inventory is a near comprehensive list of enterprise datasets within government—all the spreadsheets, records, and databases that government agencies create and use internally to make decisions. Its release is an important step for improved transparency, accountability, and efficiency.

For the public, the inventory provides a look into the government’s operations and assets. It helps foster a more informed public and is particularly valuable for filing public records requests. It also helps District government. This is the first time an inventory like this has been seen by the public or government; no agency previously had a good sense of the data assets of another. The inventory has the potential to promote greater agency collaboration—or at least data-sharing—and support citywide initiatives.

D.C. is maybe a little late to the game: New York City published their first inventory in 2013, and over a dozen other cities have done so since then. But D.C.’s data inventory is more detailed than most cities’, including information on the frequency with which data is updated; the public interest in the data, as measured in most cases by public records requests; and a classification of data by openness (a measure that is explained in the Chief Data Officer’s annual report, which accompanies the inventory release).

What’s included in the Enterprise Dataset Inventory—and why it’s incomplete

D.C.’s inventory lists 1,640 enterprise datasets. While it likely covers most of the government’s datasets, the inventory is by no means comprehensive. The reason why is indicative of some of the challenges of citywide data efforts and weaknesses within D.C.’s Data Policy.

Listing all available datasets within an organization is not an easy or straightforward task. Agency data is typically heavily siloed, and each agency may have its own way of collecting, organizing, and storing the data its workers use and share internally. D.C.’s open data portal is a cross-agency data initiative that provides a start, but is limited to open data—datasets that have already been prepared and published for public use. When setting out to inventory all District government data, the CDO had a limited view into any agency’s data beyond that which is currently on the open data portal.

The inventory relies on Agency Data Officers (ADOs), designated employees within each agency that work as the connection between their agency and the CDO to ensure policy compliance and work to complete their agency’s part of the inventory. It is not necessarily an easy task for ADOs to identify data within their own agencies, particularly large agencies that will have siloes of their own. This initiative has no funding, so ADOs have to take on the task of cataloging their agency’s internal datasets on top of their prior responsibilities.

The relationship between ADOs and the CDO is based on goodwill and trust. The Data Policy does not include any compliance mechanisms to ensure ADOs’ full participation in the inventory or other portions of the policy. There are no checks in place on the completeness or accuracy of information ADOs provide to the inventory.

A preliminary examination shows that the inventory is missing datasets that have already been published elsewhere. For instance, the Enterprise Dataset Inventory does not list illegal construction complaints made to the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs (DCRA), yet this data is published on DCRA’s own data portal. Complaint data seems to be commonly overlooked throughout the inventory, including American Disability Act (ADA) complaints filed to the Office of Disability Right and early learning complaints filed to the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). DC Water’s listed data doesn’t seem to include water main breaks, which is published on DC Water’s data portal.

The inventory is a good first step, but without resources for agencies, compliance mechanisms for the CDO, and a law (which provides more weight than internal policy), it will likely remain incomplete.

A successful inventory will need greater agency participation

The CDO recommends that inventory participation should be included in future Key Performance Indicators for agencies with metrics such as the number of datasets and number of open datasets. This would help encourage agency participation, although agencies should work with the CDO to carefully consider which metrics are used to determine performance. Only tracking the number of datasets listed, for example, would not capture the quality of the data being shared, or whether it is the type of data of the most interest to the public.

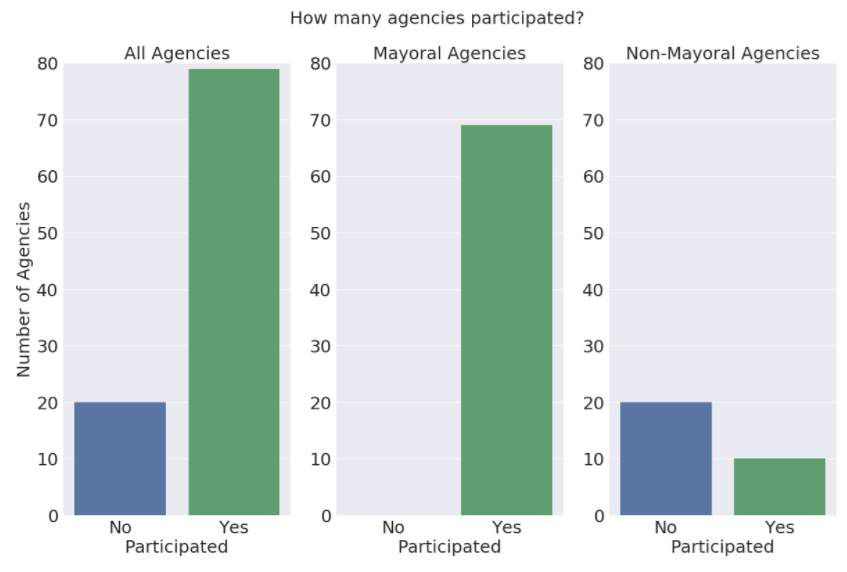

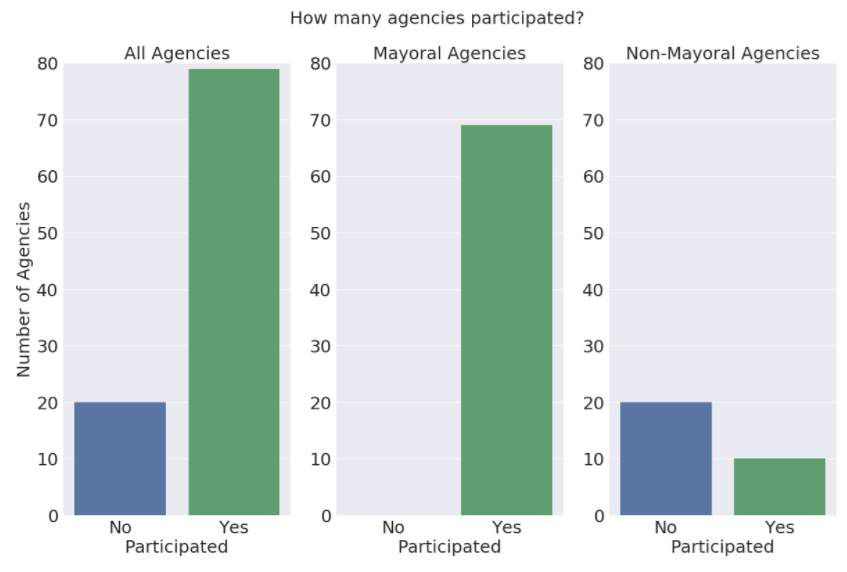

Some of the largest gaps in the inventory come from independent agencies, only a third of which participated in the inventory at all. These agencies do not sit under the Mayor, and therefore do not have to comply with the District’s Data Policy. Twenty independent agencies did not participate in the inventory at all, including the Office of Police Complaints, DC Housing Finance Agency, Office of the Inspector General, University of the District of Columbia, and, perversely, the Office of Open Government.

Only a third of independent agencies participated in D.C.’s Enterprise Dataset Inventory

Source: Chief Data Officer’s Annual Report http://opendata.dc.gov/pages/cdo-annual-report

Some independent agencies that did participate seem to have done so on a limited basis. For instance, the D.C. Public Charter School Board (DCPCSB) listed only one dataset in the inventory: the location of charter schools. Conversely, D.C. Public Schools (DCPS) listed 168 datasets on topics including hiring and staff, assessments, and finances. Charter schools do not have to report data to DCPCSB in the same way that public schools are required to do so to DCPS, and the disparity speaks to the transparency gap between public and privately-run institutions.

The accompanying report by the D.C.’s Chief Data Officer recommends that OCTO encourage future participation of independent agencies by seeking support from Deputy Mayors and, if all else fails, through legislation. Codifying the Data Policy into law is the best way to ensure the aims of the policy are followed through on long term, though it does not appear to be a current priority.

How many of the listed datasets are available to the public?

Of the 1,640 datasets listed in the inventory, 43.2 percent are categorized as open, which means the data is considered public and should be proactively released. “Open data” should be free to use and easily discoverable online in a machine-readable format,” but this is not always the case. When data is categorized as “open,” it does not mean the data is currently open and shared, as defined in the Data Policy—only that it should be. Just under three-quarters of data classified as open is actually available on D.C.’s open data portal.

Some data that has been classified as “open,” like data on the District’s Private Security Camera Voucher and Rebate Program, is not online at all. Other “open” datasets, like lobbyist activity, are online, but not in a machine-readable format. The report indicates that OCTO will work with individual agencies, the Open Government Advisory Group, and the public to prioritize publishing datasets to the open data portal, but it does not specify a timeline.

The remaining 932 datasets are not classified as open for security or legal reasons. But this does not mean some version of the dataset cannot be made publicly available. For instance, data on taxicabs trips cannot be published in its raw form because it includes personally-identifiable information. However, the taxicab dataset is currently open and online: personally-identified information has been removed or scrambled to address privacy concerns. Similarly, the data inventory identifies school enrollment audit data as confidential, yet a version is already published by the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE).

Beyond “open data”

Data inventories are a great starting point for better government data, open or otherwise. It can be a tendency of data inventories, however, to define success quantitatively. There are 1,640 datasets listed this year, of which over 700 are considered open. It is easy to define success going forward as increasing the number of datasets inventoried and published. That would be a mistake.

Efforts to make government data available to the public cannot solely focus on the low-hanging fruit of data already classified as open, which does not require additional privacy or legal considerations before release. Rather, it’s important to consider data that can result in the greatest community benefit, whether it be for research, transparency, accountability or engagement, regardless of classification. Police use of force data is not classified as open, but it has substantial community value.

A focus on quality extends to the data once it’s accessible online. The Data Policy defines open data, in part, as data that is documented. Arguably, almost no District government data meets that standard. Datasets are routinely published on D.C.’s open data portal with limited metadata and no data dictionary. A particularly glaring example is what the District government has submitted as property transfer data to the U.S. Open City Census. If it is, in fact, a dataset about property transfers, which may include sales, mortgages or foreclosure information, there is absolutely no indication of that to the user. The dataset is confusingly named “Land Boundary Changes.” The description of the dataset is:

Owner polygons. The dataset contains locations and attributes of owner polygons, created as part of the DC Geographic Information System (DC GIS) for the D.C. Office of the Chief Technology Officer (OCTO) and participating D.C. government agencies. The tax information (attribution) comes from OTR’s Public Extract file. The creation of this layer is automated, occurs weekly, and uses the most currently available tax information. The date of the extract can be found in the EXTRACTDATfield in this layer. Please visit http://vpm.dc.gov/ for additional information. All DC GIS data is stored and exported in Maryland State Plane coordinates NAD 83 meters.

The metadata is extremely limited, and just as unhelpful. A published dataset is not an open dataset if its contents are indiscernible to a data practitioner, much less a layperson.

In the CDO’s annual report, one goal for the coming year is the creation of a data submission guide, which would provide a blueprint and minimum standards to agencies for data publishing. This is a crucial part of making data not just available, but usable. New York City and San Francisco have similar guides. The Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center provides particularly good resources for data publishing.

The District’s Enterprise Dataset Inventory is an important asset for transparency, accountability, and government effectiveness. Its first release is a solid effort. To truly sustain and improve the inventory, and the Data Policy more broadly, the initiative should be bolstered with resources, enforcement, and supporting legislation.

Feature photo by Ted Eytan (Source)

Kate Rabinowitz is a freelance data journalist who has previously worked at ProPublica and created DataLensDC (datalensdc.com). Her work has been featured in numerous D.C. and city-focused publications. Kate is also the co-captain of civic hacking group Code for DC.