This article is the second in a series on COVID and the District’s health care workforce, which will discuss the ecosystem of care providers relevant to COVID and primary care outcomes, evaluate patient’s access to clinicians, and measure health care capacity.

Read the other articles in the series:

The public health emergency caused by COVID-19 has increased scrutiny on the District of Columbia’s health care system. Does D.C. have adequate health care workforce capacity to handle the health care need and health care demand of its residents during this pandemic? If not, what supply gaps exist, and what impact do those gaps have on residents? To examine these questions, we turn to data from the D.C. Department of Health (DOH) and other clinical boards in the Washington metropolitan area.

In order to understand the District’s COVID-19 response, health needs of the population, and whether the existing network of health care professionals is sufficient to support the needs of the population, we must first determine how many primary care visits the population needs, and what barriers exist to getting care.

To understand the healthcare need of District residents, we asked: What drives differences in the health care needs of different groups of Washingtonians? How can our knowledge of primary care need and demand inform our understanding of the inequitable COVID-related outcomes seen in the District?

The health care needs of District residents are largely dependent on age, sex, and underlying health conditions. For example, a child is likely to see a primary care provider for school-mandated checkups, common colds, and sports injuries, while an older person is more likely to seek prescription refills and bloodwork for chronic conditions. Women are more likely to need more primary care visits than men between the onset of puberty and menopause. Age, sex, and health status (as impacted by pre-existing conditions and genetic and environmental factors) are the primary determinants of a person’s health care need. Thus, health care need is the number of annual primary care visits an individual is predicted to have based on their age, sex, and health status.

However, for various reasons, not everyone who needs health care seeks it. Health care demand is the number of annual primary care visits an individual is predicted to have, accounting for barriers such as cost, culture, education, location, and language.

In this article, we will delve into both health care need and health care demand in the District, across race, sex, and age; and discuss the differences seen in these demographic categories. We will try to explain why the expectations of need and demand for Washington’s health care clinicians (HCCs) are not identical across place and group.

A snapshot of overall health care need and demand in the District

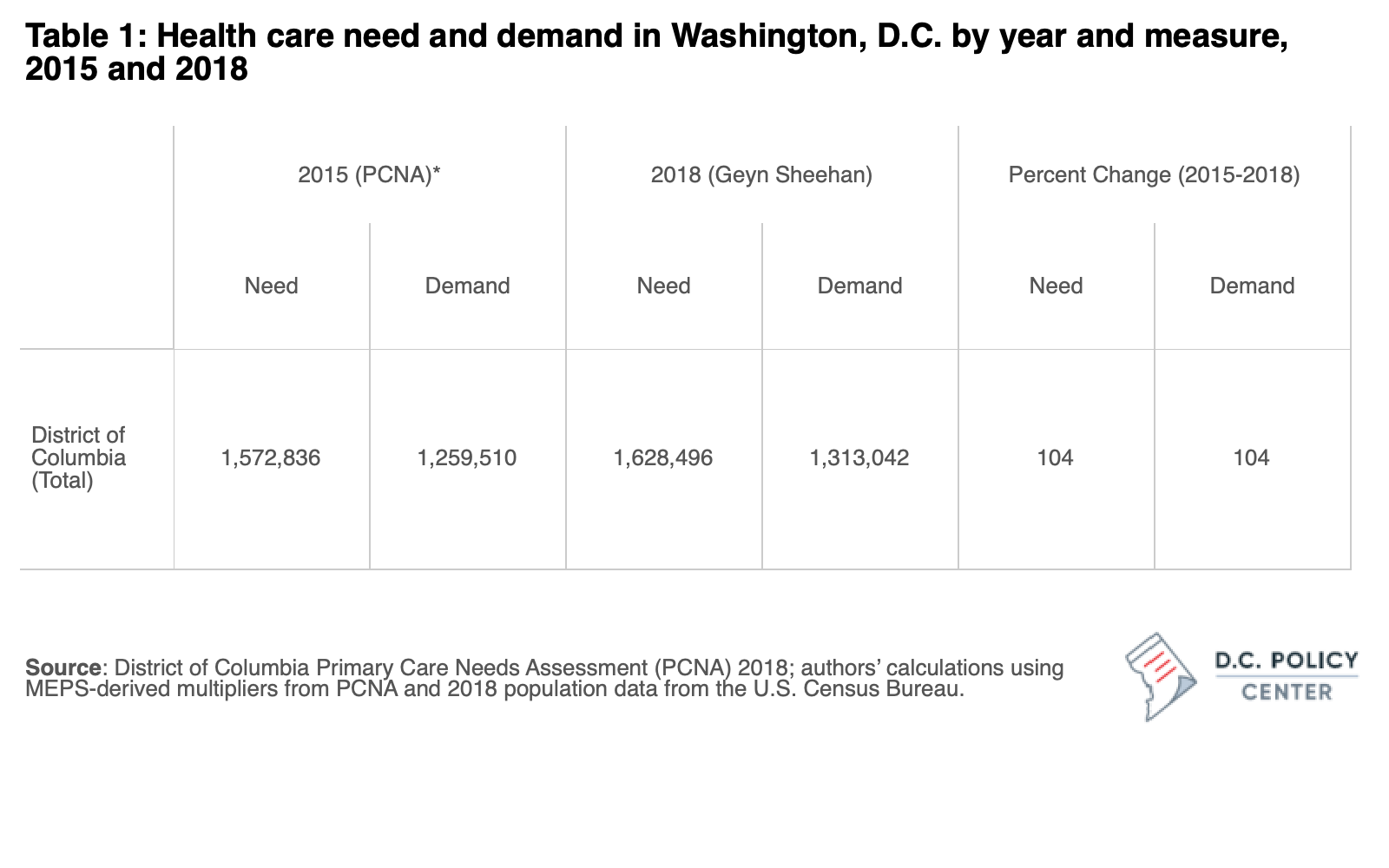

Health care need and demand increased in the District from 2015 to 2018, as the population increased. The table below describes need and demand in Washington, D.C. in 2015 and 2018. In 2015, D.C.’s approximately 647,000 residents had a health care need of about 1.57 million primary care visits and a demand of 1.26 million visits, reflecting the barriers to health care access mentioned earlier. With a population increase to about 684,000 in 2018, need and demand both increased by 104 percent, revealing that barriers to care impeded almost 320,000 primary care visits that year.

While we cannot estimate the number of primary care visits an individual person may need, we can estimate the number of visits needed at the population level by factoring in age, sex, and health status of the locality. Age intuitively drives health care need: children, adults, and older people use health care in different ways. Need also varies by sex, particularly after puberty.

Health care need is also highly dependent on health status, which includes a confluence of factors driven by nature (genetics), nurture (the environment in which people live and work), and lifestyle (factors including exercise and diet). Health status can be measured at the population-level in several ways including life expectancy, self-assessed surveys of health status, or number of physically and mentally unhealthy days in the past 30 days.

We estimate demand by adjusting need to reflect real-life barriers such as culture, economics, education, insurance status, and language. To generate estimates of need and demand for D.C. overall and for its subpopulations, we multiplied population counts by Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) multipliers from the 2018 PCNA report that consider the previously discussed factors.[1]

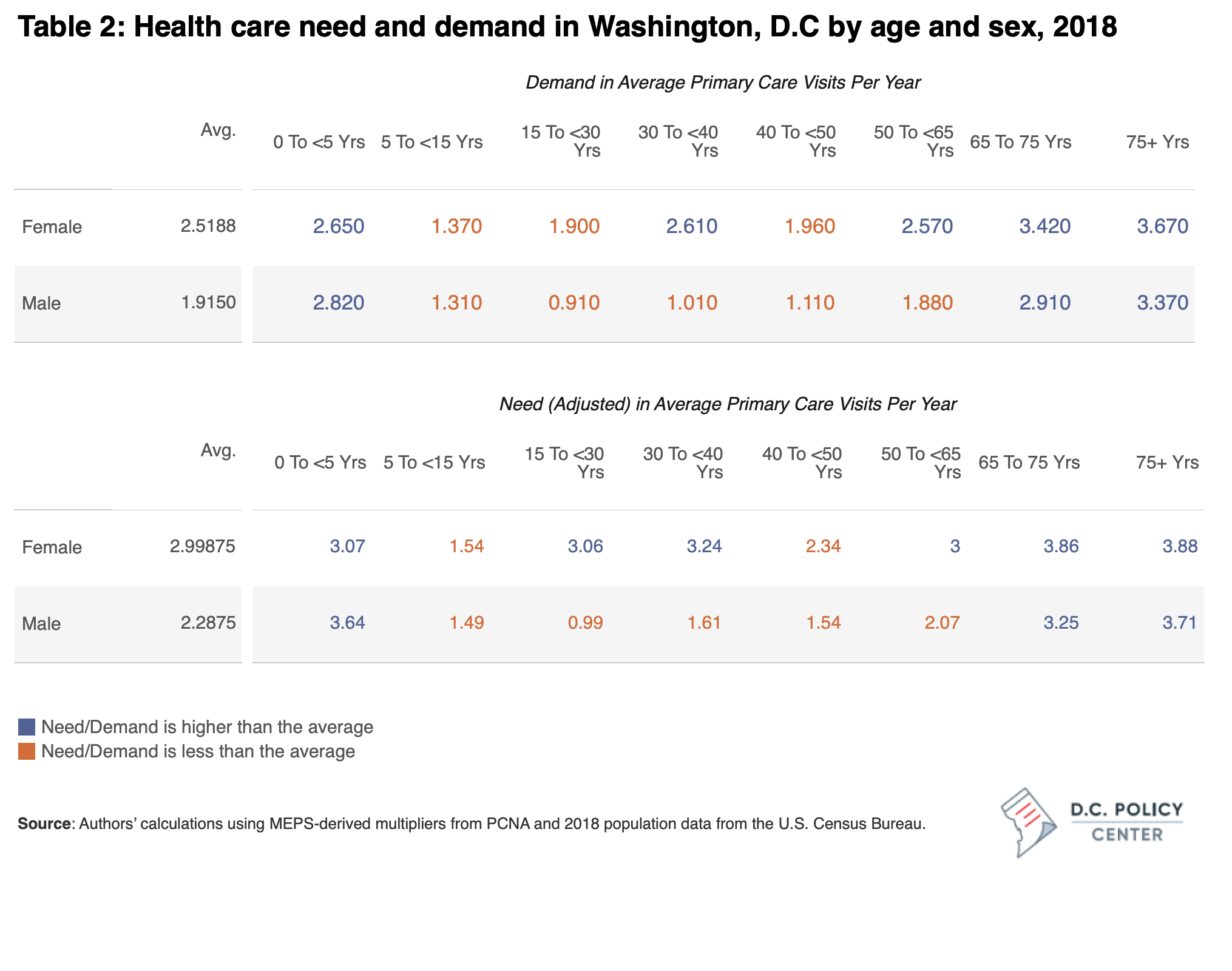

In D.C., need and demand fluctuate by age and sex in predictable ways. Table 2 shows estimates of the average need for health care visits and the demand by age and sex in DC. For instance, the average male needs 2.3 primary health care visits per year, but when adjusted for barriers, they demand 1.9 visits. Children, women of reproductive age, and older adults need more primary care than the general population. When accounting for care-seeking barriers, demand is higher for these populations as well.

D.C.’s racial disparities in health care need and demand

The method used to calculate need and demand in this study relies on multipliers derived from the MEPS, which does not provide race-specific estimates. However, we do have data on race-based differences in the age distribution and can use these estimates to approximate racial disparities in health care need and demand.

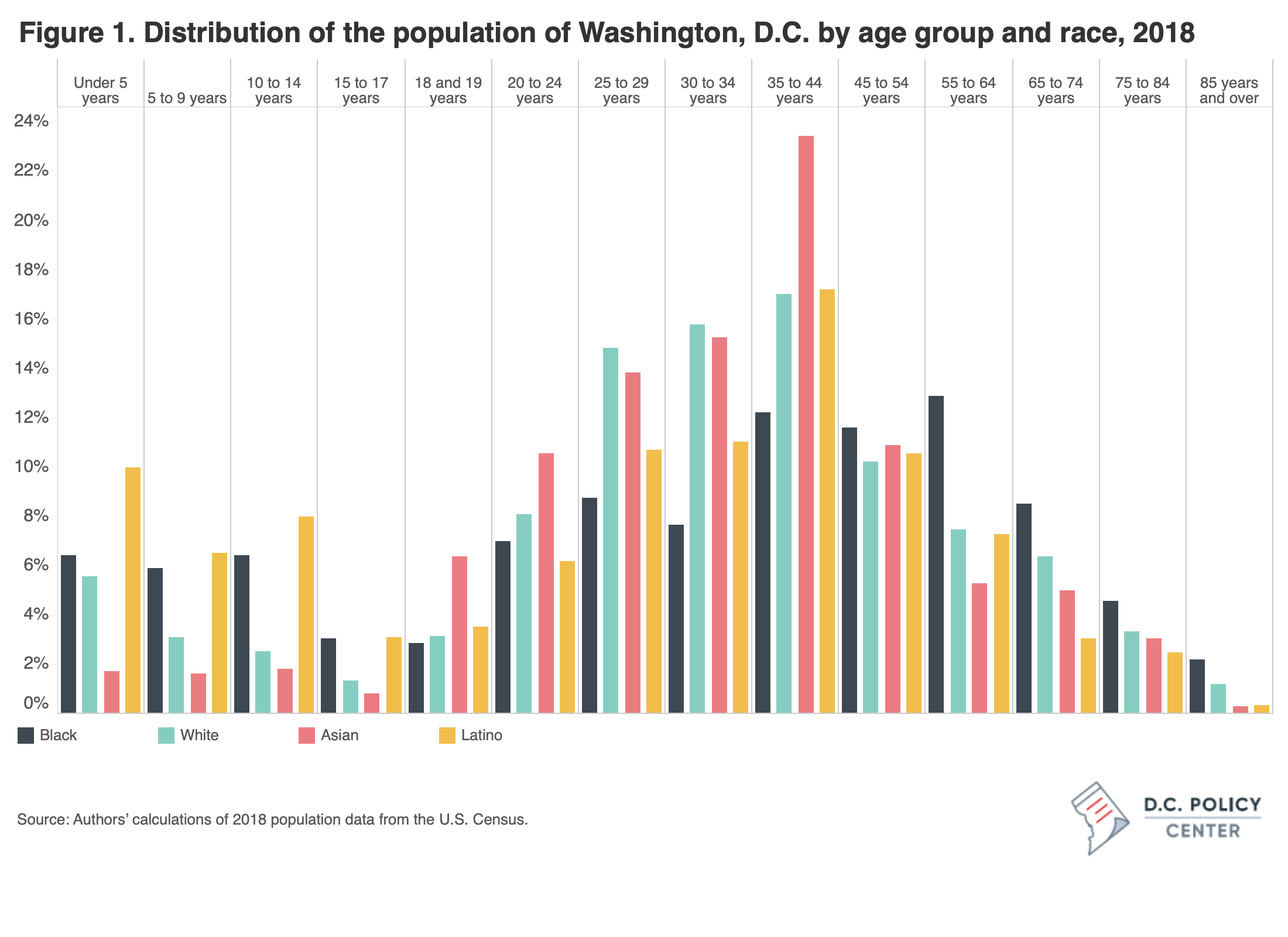

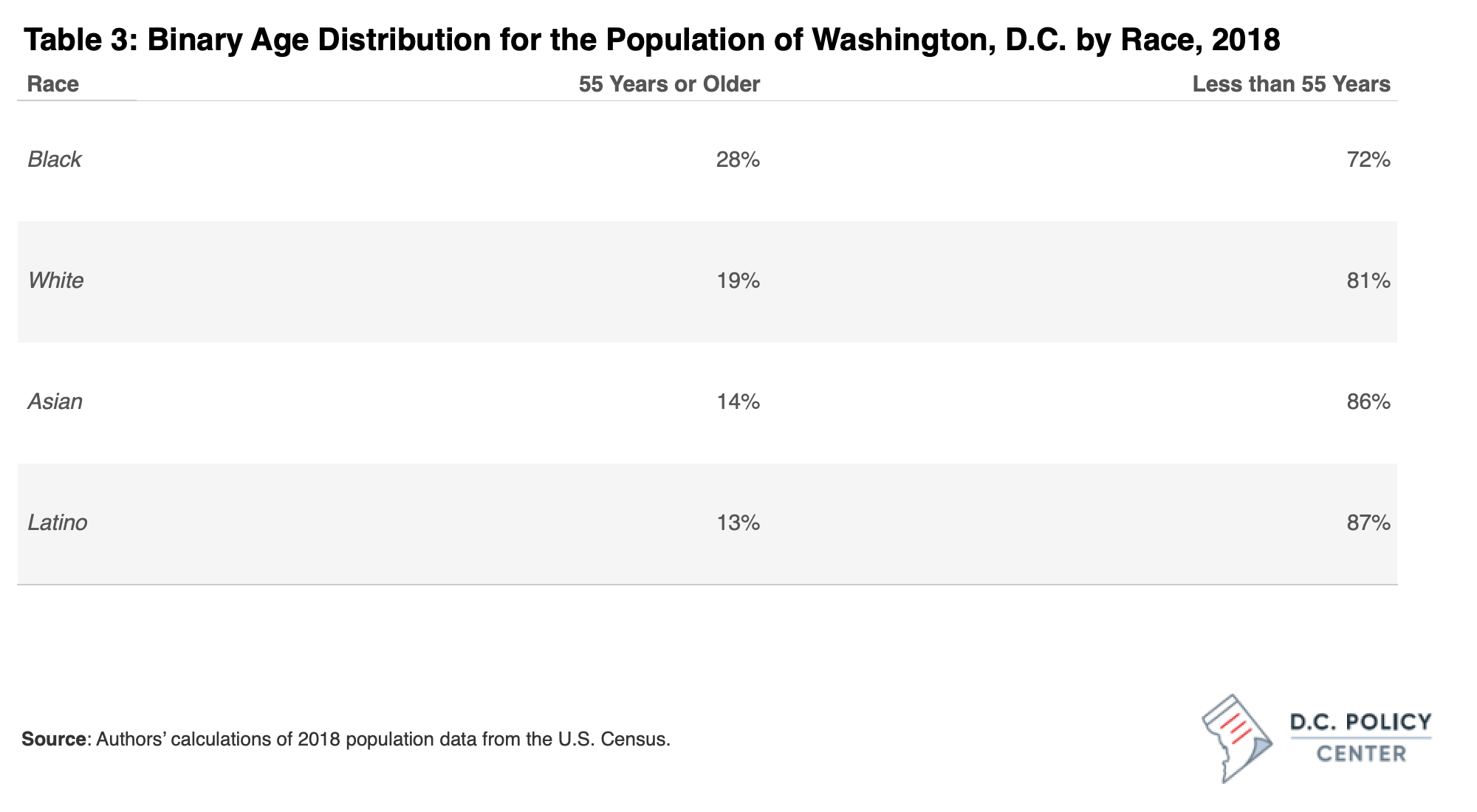

There are important differences in the age distribution of D.C. residents by race. D.C.’s Black population skews older than the white population, and is more evenly distributed across age groups than other racial groups. 28% of Black D.C. residents are over 55, whereas 19% of white residents are over 55. The white and Asian population tend to be concentrated in prime working years between 25-55, and the Latinx population is somewhat bimodal between those 25-44 and the youngest age groups. These differences are visualized in Figure 1, below.

These factors make the Black population more vulnerable to more serious COVID infections if exposed to the coronavirus, and also makes them more likely to have higher health care need and demand.

These racial differences in age distribution translate into differences in health care need and demand: there are significantly higher shares of elderly residents among Black Washingtonians, relatively higher shares of children among Latinx Washingtonians, while white and Asian Washingtonians are typically working-aged. Because older individuals and children need more primary care visits than non-elderly adults, we conclude that Latinx and Black residents need, per capita, more primary care visits than white or Asian residents. While we do not have data that specifically speaks to how race affects health care need and demand in the District, we know that there are differences in underlying health conditions and healthcare seeking behaviors by race.

Causes and contributing factors to the racial disparities in need and demand

The racial health disparity in the District is shaped by years of systemic and structural forces. Black and Latinx residents have a significantly lower average income and levels of educational attainment than white residents, both of which are factors that impact health status. Black and Latinx residents are also more likely to be exposed to pollutants in the air, water, and soil, as well as stressors like poverty and crime.

The 2015 The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) reported that while only 3 percent of white D.C. residents said they were in poor to fair health, 19 percent of Black residents rated their health poor to fair (as compared to 9.1 percent of residents of other races).[2] BRFSS is a subjective measure that nonetheless aligns with known disease rates in the District: predominantly Black and Latinx neighborhoods in D.C. have higher rates of hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, stroke, and other chronic health problems than predominantly white neighborhoods.[3]

Knowing this, while the population-level distribution of age would predict that Black and Latinx populations have greater health care needs relative to white and Asian populations due to the self-reported health status and disease prevalence rates we observe, we believe that the per capita health care need above is underreported. This would mean that the disparity between health care need and demand is likely greater than we previously reported.

Other racial disparities in the District’s health care system: Unmet need and health insurance

In addition to having proportionally greater health care need than white residents, Black and Latinx populations likely have a larger gap between need and demand. On top of elevated anticipated need based on the age distribution, barriers such as language, culture, education, and cost (considered when calculating health care demand), are likely to be higher for Black and Latinx populations. Data on health care need and demand by race and ethnicity should be collected and made publicly available to determine the disparity in the District with specificity.

There is also a lingering question of health care insurance: While over 97 percent of white residents and 94 percent of Black residents are insured, just 87 percent of Latinx residents have health insurance. The overall insurance rate in D.C. famously exceeds that of other major metro areas, but even here we see a substantial disparity. Health care is unsustainably expensive without insurance, often prohibiting those without insurance from seeking care. Even individuals covered by insurance may be burdened by barriers including high co-pays, out-of-pocket expenses, and unexpected charges.

Language is another common barrier to obtaining health care, especially in D.C., where there are 168 languages spoken primarily in the home.[4] Nationally, more than 20 percent of those with limited English proficiency are uninsured, and therefore less likely to seek care.[5] Additional barriers that may impede demand for Black and Latinx groups include distrust of the medical system and lack of access or experience with telemedicine.[6][7]

Heath care disparities and COVID-19

We hypothesize that the same populations with greatest unmet need are the population being hit hardest by COVID.

While Washington is unique, its experience with COVID is eerily familiar to many areas of America. In the District, Black residents account for 74 percent of the lives lost due to COVID as of January 10, 2021.[8] Latinx residents make up nearly one-quarter (22 percent) of D.C.’s individuals who have tested positive, despite making up just 11 percent of the District’s population.[9]

The hypothesized greater amount of unmet health care need that exists for Black and Latinx populations is one of many possible factors causing inequitable COVID outcomes. However, by measuring neighborhoods’ unmet need and identifying culturally-specific barriers to health care utilization, D.C. can reduce the number of residents not receiving adequate primary care, and improve health outcomes in demographics most underserved.

The next paper in this series will examine:

- Who makes up D.C.’s workforce and what are the identifiable trends in the District’s health care workforce?

- How does D.C.’s workforce capacity compare to the capacities of states and to similar metropolitan areas?