This article is part four in a series focusing on circumferential transit in the Washington, D.C. region. Read part one, part two, part three, and part four.

While Maryland’s Purple Line is the biggest suburb-to-suburb transit project in the region, Virginia also has a number of corridors that are good candidates for this kind of connection. Northern Virginia has a particular need for such projects because it has so many large suburban job centers. Unlike the I-270 Corridor in Montgomery County, they are not all generally in the same radial corridor, and so cannot easily be served by radial transit lines.

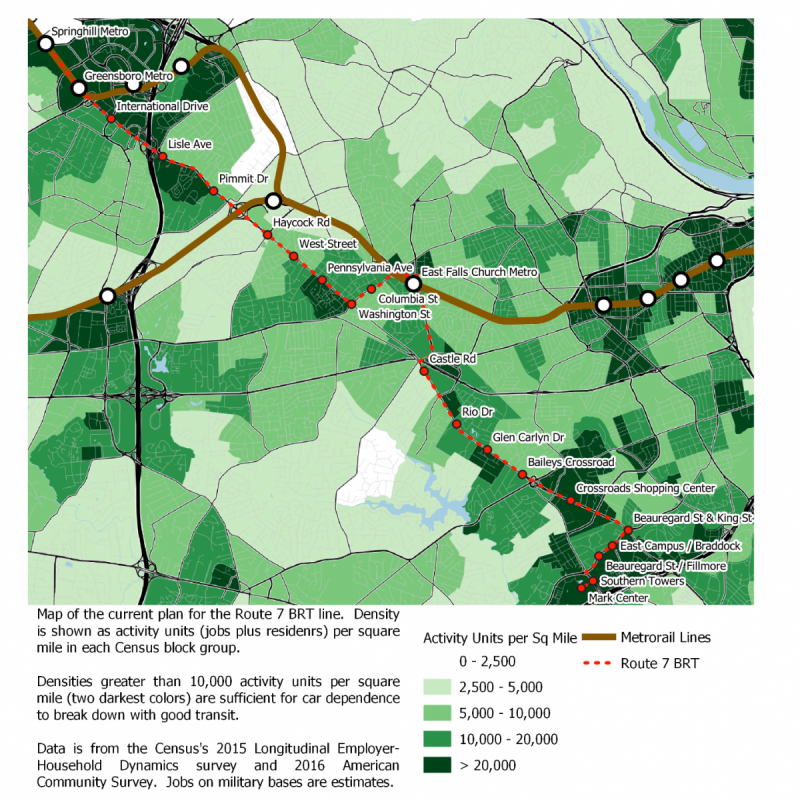

While no light rail lines are currently being planned in Northern Virginia, there are fortunately plans for a major circumferential-like Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) corridor that will provide important service along Route 7 between Tysons and Alexandria. This corridor, along with the separate West End Transitway being planned by the City of Alexandria, will play a significant role in knitting together dense development in the northern and southern parts of Northern Virginia with transit.

Virginia’s Route 7 BRT will serve an important corridor

Since 2015, the Northern Virginia Transportation Commission has been studying a suburb-to-suburb transit line between Tysons and Alexandria along Virginia Route 7/Leesburg Pike. The selected route starts at the Spring Hill Metro station in Tysons, and largely stays on Route 7, with a short diversion to the East Falls Church Metro station.

Rather than following Route 7 to King Street (which would involve passing through single-family home neighborhoods on a two-lane road with little opportunity for dedicated lanes, and extremely low ridership potential), the line turns west on Beauregard Street. It then follows Alexandria’s planned West End Transitway route to the Department of Defense’s Mark Center, just north of I-395. Buses might continue south via the West End Transitway to Van Dorn Metro station, although that kind of operational detail hasn’t yet been finalized.

This route provides useful connections both within the corridor itself and to the Silver and Orange lines. The area has significant density—nearly the entire corridor has more than 10,000 activity units (jobs plus residents) per square mile, which means frequent transit can significantly reduce automobile dependence. And with BRT in place, more density is practical.

This will also provide a connection to the Mark Center, a major Department of Defense job site with over 6,500 workers. Many of these jobs were relocated away from transit-oriented locations such as Crystal City during the 2005 round of base realignments and closures. The region would benefit from making them transit-accessible again.

Route 7 buses will mostly have their own lanes, which means faster trips

Although light rail would have provided some advantages over BRT, including higher overall capacity, the BRT alternative that the Northern Virginia Transportation Commission selected will be high-investment, legitimate BRT with a dedicated lane for most of the route. From the Spring Hill Metro station in Tysons to West Street in Falls Church, the line will run in a median transitway. That’s generally considered the best option for BRT since buses will not be delayed by drivers making right turns.

Unfortunately, the narrowness of Route 7 in Falls Church led to the decision not to have a dedicated lane between West Street and the East Falls Church Metro station. Rather than simply running buses in mixed traffic, the line would have “Business Access Transit” (BAT) lanes. These lanes are reserved for buses and vehicles making right turns, which reduces congestion somewhat.

South of Falls Church, the line will again run in a dedicated lane until it turns off Route 7 onto Beauregard Street in Alexandria, where it joins the route of Alexandria’s planned West End Transitway BRT. Here, unfortunately, the plan is to run in mixed traffic to the Mark Center. Despite the mixed-traffic portions of the line, the average speed over the length of the route is estimated to be about 18 mph (including time spent stopped at stations), which is a pretty good speed for urban travel.

The West End Transitway could complete the suburb-to-suburb link

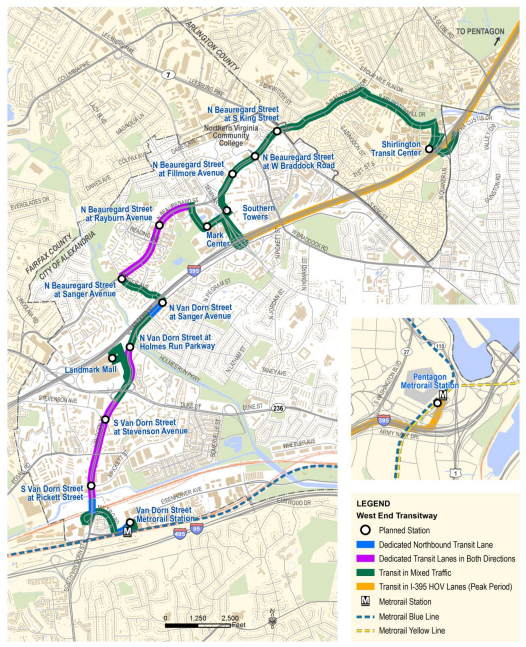

South from the Mark Center to Van Dorn Street Metro station, the City of Alexandria’s West End Transitway BRT project will link the Pentagon and Van Dorn Street Metro stations, and provide a useful path for Route 7 buses to potentially continue all the way to the Blue Line.

Northeast of the Mark Center, West End Transitway buses would run in mixed traffic along the same Beauregard Street route as the Route 7 BRT, then turn to continue along Walter Reed Drive to the Shirlington Transit Center, from where they could use the I-395 HOT lanes to reach the Pentagon. Southwest of the Mark Center, however, much of the route to Van Dorn Street would be in dedicated transit lanes.

The proposed Alexandria West End Transitway. Image by City of Alexandria. (Source)

These dedicated transit lanes would allow significantly faster bus service from the Mark Center to Van Dorn Street, especially at rush hour. If the Route 7 BRT eventually uses them as well to create a East Falls Church-Van Dorn Street one-seat bus connection, this would make its southern end into a more truly circumferential service.

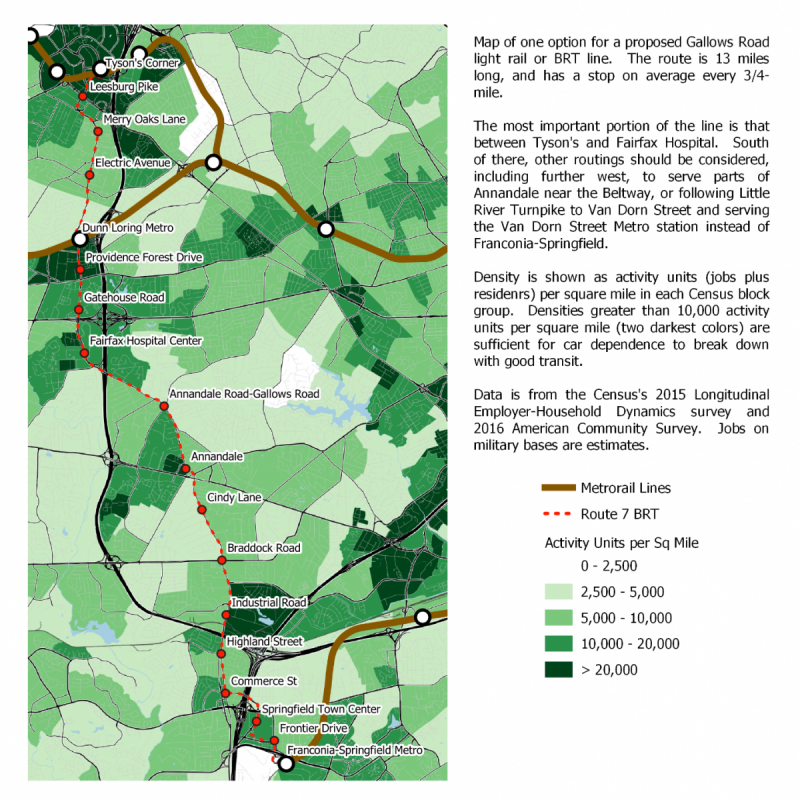

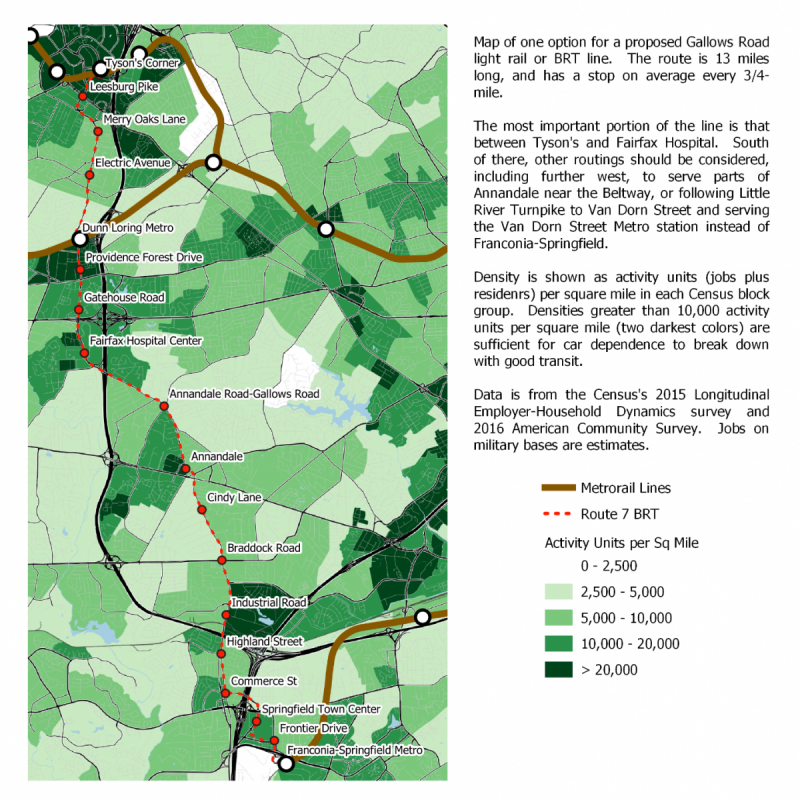

A Transit Line is Needed on Gallows Road, Paralleling the Beltway

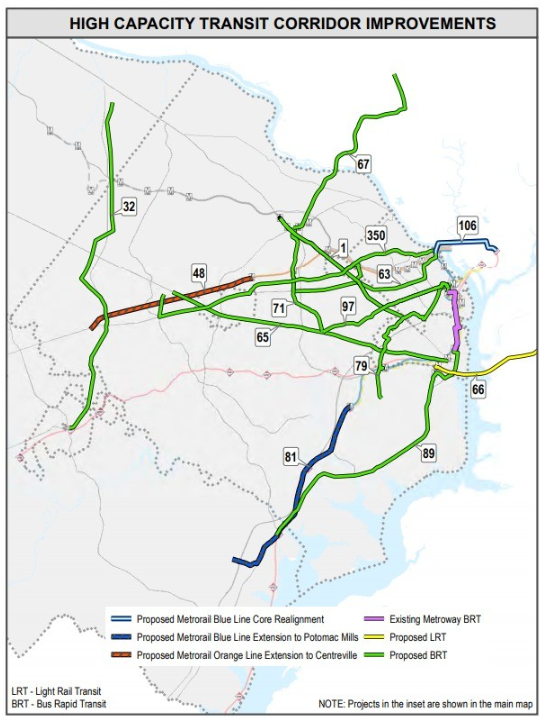

In addition to the Route 7 and West End projects, there is a major opportunity for a circumferential BRT or light rail line further west in Fairfax County, roughly paralleling the Beltway from Tysons south.

My proposed routing for a Tysons-Franconia Springfield BRT or Light Rail line. Note that the apparent high density at the Industrial Road station is spurious: it is due to Fairfax County Public Schools listing all their employees, who work throughout the school system, at the address of the Board of Education. Image by the author.

Density in Fairfax County is very patchy, with significant development in corridors—usually along freeways—surrounded by much lower-density single-family homes and open space. In the case of the western portion of the Beltway, there are several areas that are dense enough to make a reasonable suburb-to-suburb transit corridor linking the Silver, Orange, and Blue lines. These include Tysons, of course, as well as the Dunn Loring-Fairfax Hospital area, Annandale, and Springfield.

Since many of the densest parts of these communities are beyond walking distance from nearby-but-not-close-enough Metro stations, a BRT line here would have a lot of value. It would also feed Tysons—the region’s second largest job center after downtown D.C.—as a sort of radial.

Starting from Tysons, the likely route would be to run the line south in a median transitway along Gallows Road to the Dunn Loring Metro station. A line could also potentially be built along the Beltway right-of-way. South of the Dunn Loring station, the median of Gallows Road is definitely the best option, as it would run through the center of the densely built-up and increasingly walkable Merrifield area, and connect well to the Fairfax Hospital Center.

The northern portion of this route is by far the strongest, and may be justified solely on its own. However, there are two possible routes where the line could plausibly be continued south.

Following the Beltway right-of-way (possibly in the Beltway HOT lanes) is a plausible option, and would allow service to several developments along the edge of the freeway in Annandale. Such a line would then eventually run to the Franconia-Springfield Metro station.

Alternately, a line could continue south on Gallows Road and Annandale Road to Annandale center. From there, it could follow Backlick Road to the Franconia-Springfield Metro station or Little River Turnpike to the Van Dorn Street Metro station. Either of these options, however, would require significant distances on roads that may not be wide enough for a dedicated median transitway, and would largely pass through low-density single-family housing except at their end points and in central Annandale.

The full line via Annandale center to Franconia-Springfield would be 13 miles long and, assuming a speed of roughly 15 miles per hour, would take roughly 50 minutes from end to end. That’s slightly faster than a trip between these stations via the Silver and Blue lines, with the added benefit of better connecting surrounding communities to Fairfax County job clusters.

This central Annandale routing has made it into the Northern Virginia Transportation Authority’s (NVTA) long range vision plan as a potential future project.

If it was built as a light rail line, it could potentially be part of a Virginia extension of the Purple Line, as I proposed in my third post. However, the fact that the Purple Line is a Maryland Transit Administration project would make any extension to Virginia bureaucratically complicated, and it would likely be much easier to construct this line as a separate project.

As I discussed in the second post in this series, a Purple Line extension to Tysons would bring the line close to its maximum practical length. Continuing it to Dunn Loring and the Fairfax Hospital Center might work, but it would be impractical to run it all the way to Franconia-Springfield. Instead, it would be far better to build this line as a separate project, with a transfer to the Purple and Silver lines at Tysons.

Transit across the Woodrow Wilson Bridge?

When the replacement Woodrow Wilson Bridge was built in the early 2000s, it was built with two unused median lanes intended for potential rail or other transit use in the future. The same NVTA vision plan that includes the Gallows Road line also includes a light rail line across Wilson Bridge. Thus far, no detailed planning has been done for this corridor, beyond the vision plan.

A potential rail crossing of the Potomac that doesn’t require a new bridge or tunnel is certainly not an option to be ignored. However, the bridge’s location is not optimal for this purpose. It is far enough south of downtown DC that any line using it would solely serve suburb-to-suburb trips. The southern portion of Prince George’s County is not particularly dense, and is particularly lacking in non-residential destinations besides National Harbor. Still, it is worth looking into what possible destinations for the line would be.

On the Virginia end of the bridge, Old Town Alexandria and the King Street Metro station stand out as obvious destinations. The Eisenhower Avenue Metro station might be an easier option since it wouldn’t require leaving the Beltway right-of-way, and the area around it has significant commercial development. Eisenhower is the end point of the NVTA’s vision.

In Prince George’s County, National Harbor is the most commonly-suggested destination. This would allow a significant commercial hub to be linked to rapid transit, but it would have the downside of being a dead end. South of National Harbor are very low density cul-de-sac single-family residential communities without good corridors for transit.

Further to the north in Prince George’s County, a Woodrow Wilson Bridge line could potentially run north on Indian Head Highway into Southeast DC, or else run east along Oxon Hill and St. Barnabas Roads.

NVTA’s plan keeps the light rail line in the Beltway right-of-way until it reaches Branch Avenue Metro station, where it meets the Green Line and ends. This would provide a link between two adjacent Metro lines, but the area around Branch Avenue is not very dense, and this routing would probably not attract many riders to intermediate stops in Maryland. A stop along the Beltway could plausibly serve the MGM National Harbor casino, but the main portion of the National Harbor development would be more than a mile south of the station.

While NVTA’s proposal for light rail across the Wilson Bridge does not serve much density on the Maryland side of the bridge, there are a number of corridors in Prince George’s and Montgomery Counties that could greatly benefit from rapid bus service or even light rail. I’ll discuss these opportunities at length next week.

This article is part five in a series focusing on circumferential transit in the Washington, D.C. region. Continue reading part six.

Feature image by Northern Virginia Transportation Commission. This article also appeared at Greater Greater Washington.

DW Rowlands is an adjunct chemistry professor and Prince George’s County native, currently living in College Park. More of their writing on transportation-related and other topics can be found on their website. They also write for Greater Greater Washington, where they are on the Elections Committee. In their spare time, they volunteer for Prince George’s Advocates for Community-Based Transit. However, the views expressed here are their own.