On October 12, 2021, D.C. Policy Center Executive Director Yesim Sayin testified before the Special Committee on COVID-19 Pandemic Recovery to share information on how the District can encourage office to residential conversions. You can read her testimony below or download a PDF version here.

Good morning, Councilmember Allen, Councilmember Gray, and the members of the Special Committee on COVID-19 Pandemic Recovery. My name is Yesim Sayin Taylor, and I am the Executive Director of the D.C. Policy Center—an independent non-partisan think tank advancing policies for a strong and vibrant economy in the District of Columbia. I thank you for the opportunity to testify on recovery.

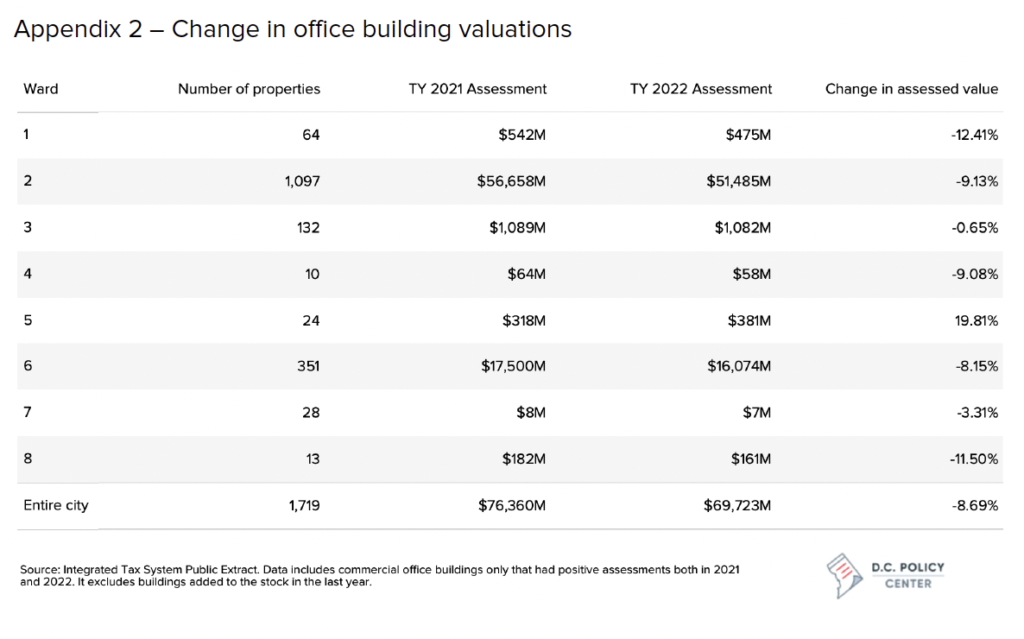

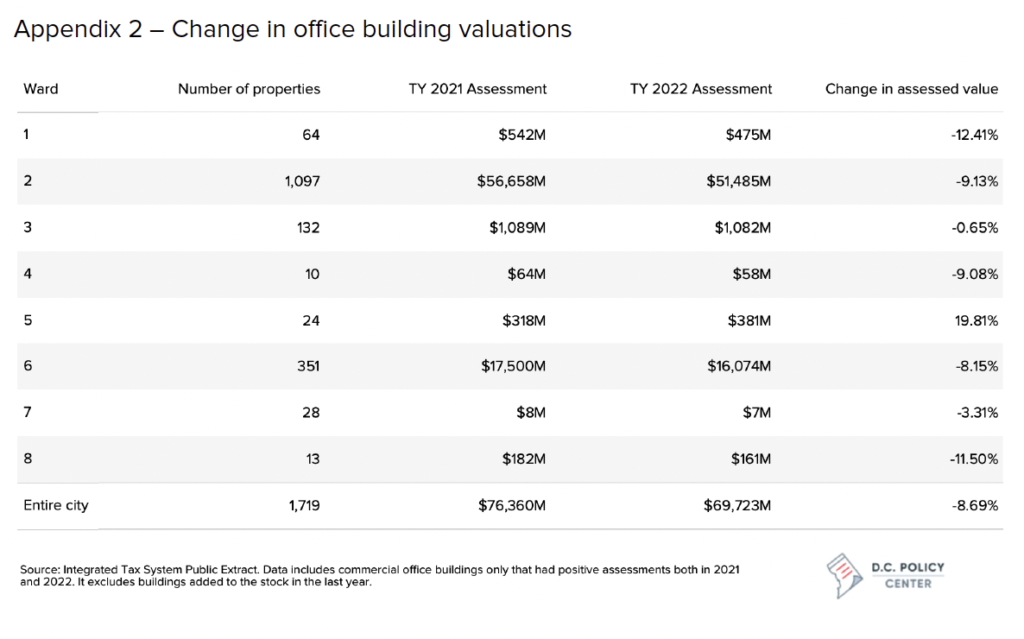

Today, I will focus my comments on conversions—specifically conversions from commercial office to residential use. The pandemic and its effects on commercial office buildings have reinvigorated the debate on conversions. And recent data from the OCFO suggest that the value differential between commercial office and residential use is declining (see appendix data). Will this induce more property owners and developers consider conversions? What can the city do to ease the path to conversions?

Conversions in D.C. are relatively rare.

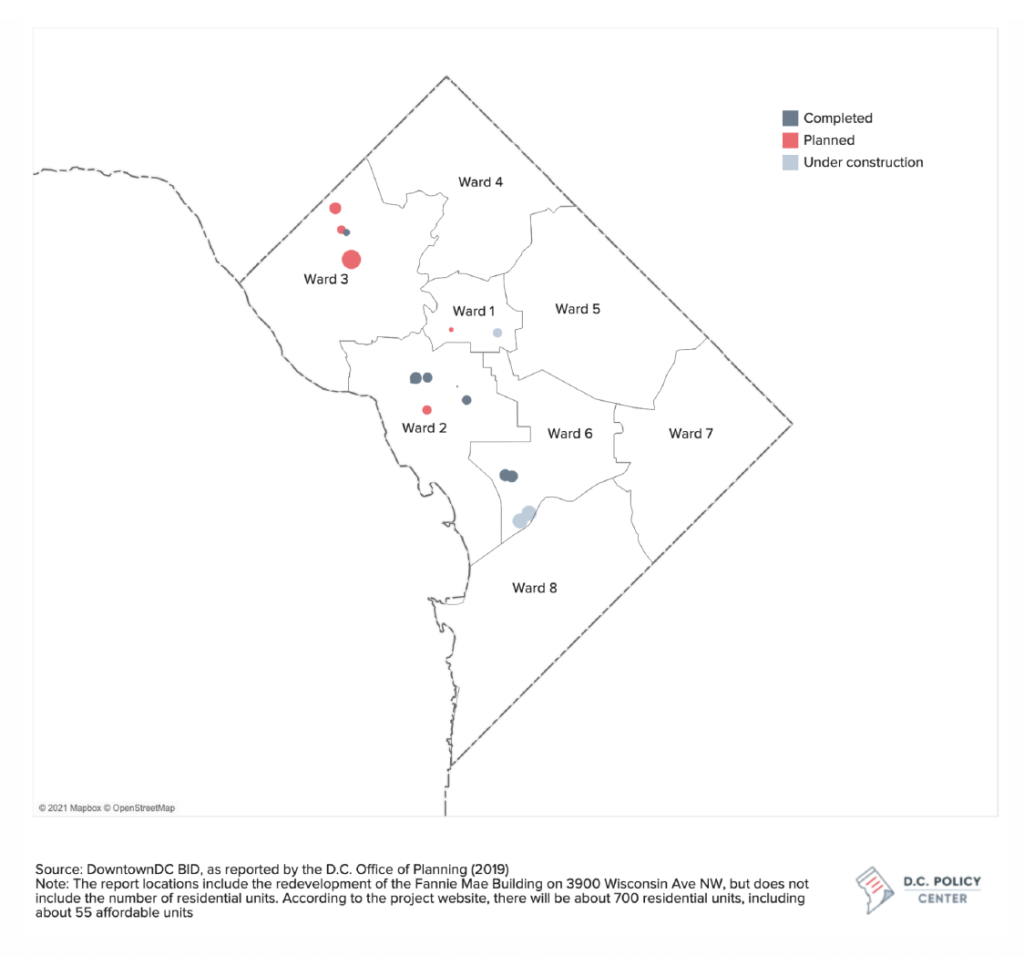

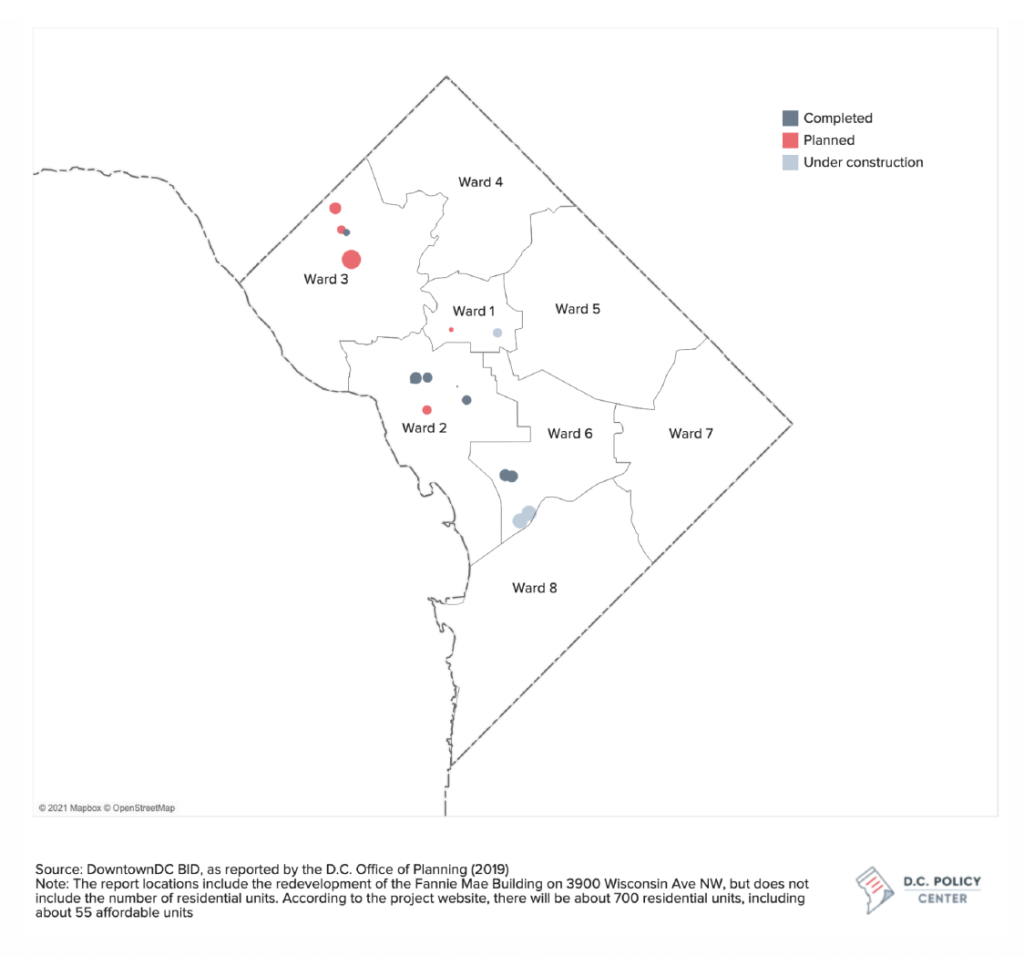

According to 2019 data collected by the Downtown D.C. Business Improvement District, since 2002, the District has seen 18 conversions (including under construction), and among those, 11 are residential conversions. These created 2,459 units.[3] Among those, 272 or about 10.6 percent are affordable, but this is largely due to a single project (Jubilee House with 176 units, which benefited from subsidies) that was entirely dedicated to affordable housing. In fact, among the conversions completed before 2019, only 23 out of over 1,371 units were affordable.

There are five other residential conversion projects that are in the works, with 1,342 planned new residential units, 9 percent of which will be affordable. As the map in the appendix shows, residential conversions happen where residential demand is strong: along Wisconsin Avenue in Ward 3, in Kalorama and along Georgia Avenue in Ward 1, in West End in Ward 2, and near the Wharf and Navy Yard in Ward 6.

Owners and developers will convert to residential if it makes financial sense.

For the landlords, the most important consideration is the net operating income from their building, which, together with the cap rate, determines the building value. In the District, on average, the valuations for commercial buildings carry about a 25 percent premium over residential buildings. The larger the gap between commercial and residential valuations, the more profitable it is to renovate and re-lease office buildings, as well as the more difficult for residential developers to compete to acquire them.

The decision to renovate, convert, or rebuild will depend on additional factors that the owner must take into consideration above and beyond the handful of factors we included in our stylized example. These factors all operate at the margin and can make or break a decision to convert for a given building. They include:

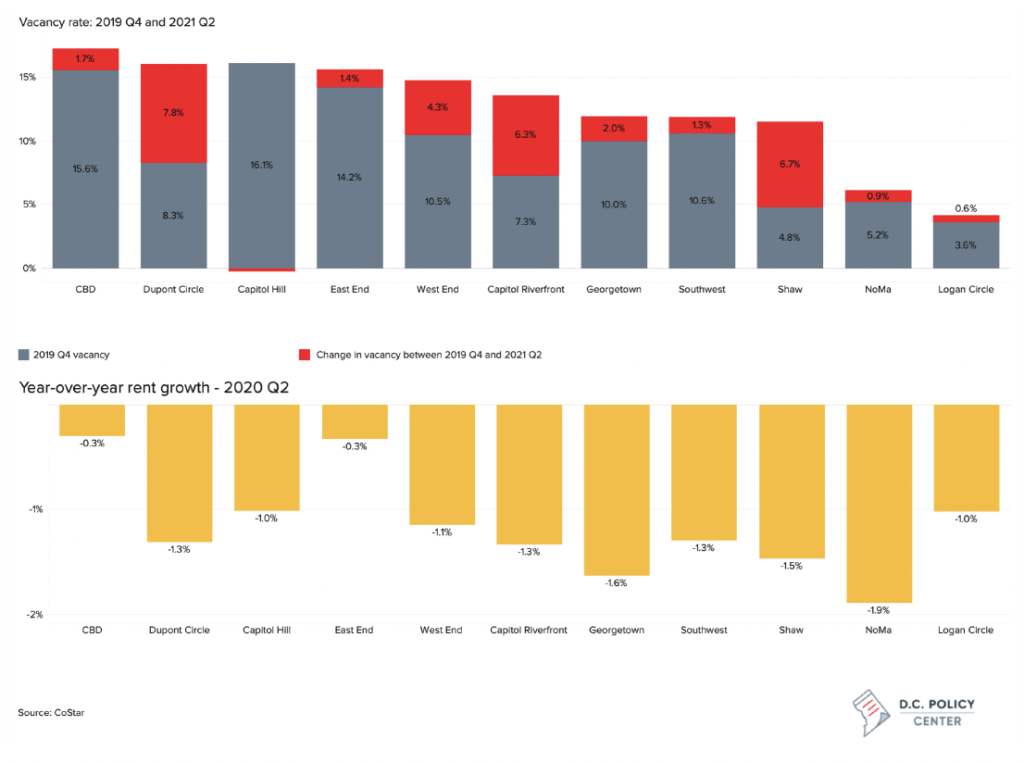

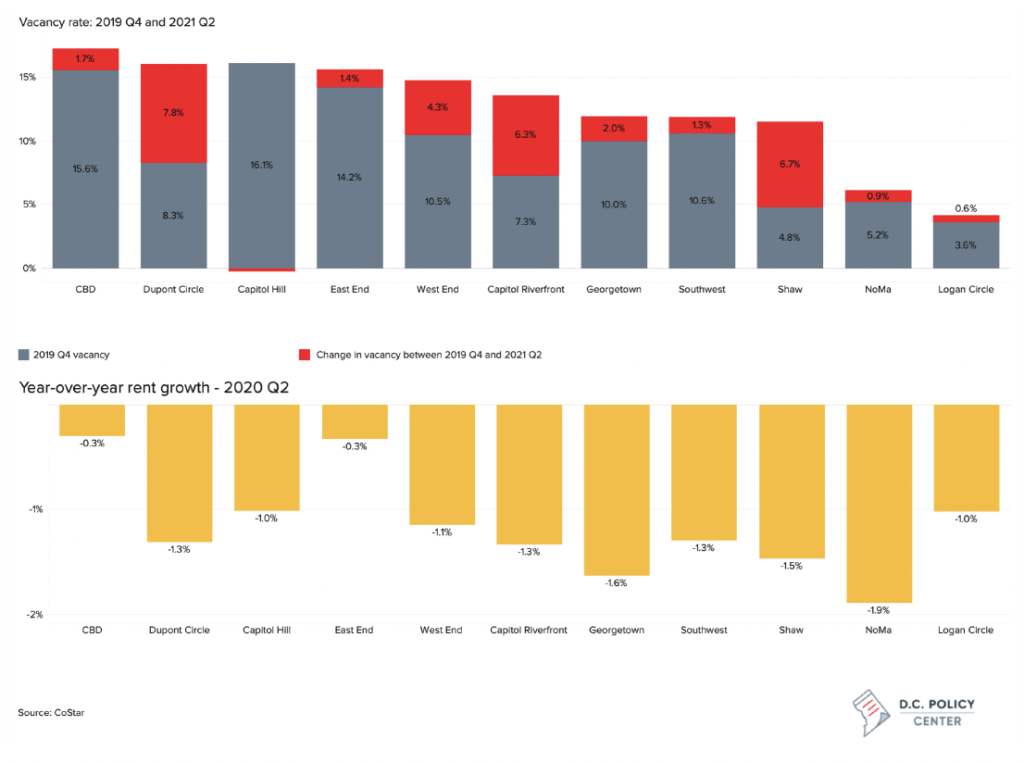

- Expectations about the future demand for office versus residential: A higher trajectory of rents for residential relative to office, an expectation of lower vacancy rates in residential unit relative to office, and lower cap rates, signaling lower risk in the residential market, for example, would make the conversion more attractive.

- Current vacancy rate: Conversions would be easier for commercial office buildings that are currently empty, or near empty. Existing leases on a property make it harder to convert because the owner would have to terminate these leases early—a costly endeavor—or wait for them to expire, which would have a high opportunity cost.

- Construction costs: Higher construction costs or bottlenecks in construction will make major renovations, including conversions, more difficult.

- Financing costs: An increase in financing costs, due to higher interest rates, higher perceptions of risk will impact the attractiveness of conversions.

- Policy risk: The owner would consider tax risk (for example, are commercial tax rates more likely to change or increase?) and regulatory risk (for example, how would building standards change and increase the cost of construction?

- Subsidies: A government subsidy for conversion, on the other hand, will increase Net Operating Income for residential use relative to baseline, and make conversions more attractive, but it would come at a double cost to D.C.: First, the city would have to cover the cost of providing the subsidy. Second, the city would potentially see a lower future tax revenue from the building, given that the tax rate on residential properties is half of the rate on commercial properties.

Even when the finances look viable, the building structure could be a barrier.

Architectural elements that are common in office buildings can make conversions a difficult task for developers. For instance, the floor plates of a building are often a great challenge when looking at converting office to housing, since apartments are legally required to have natural light access in each unit. Or since bathrooms tend to be clustered in one area of office buildings, the limited plumbing lines can be an obstacle, as a residential building in contrast would require bathrooms and plumbing in every unit. For a change in the occupancy use, residential buildings would have to coordinate units and systems around the structural floor assembly in a different way. It might need a different placement of elevators, require façade redesigns, rerouting or rebuilding of electric and plumbing lines, different HVAC loads on the roof, and higher capacity utility lines – all of which will impact the cost for developers.

Public policy itself can prevent conversions.

For example, the owner may have to seek a change in allowable use, which could be a time consuming and costly process in D.C.

Even when permitted, any requirement to include affordable units in the conversion, for example through Inclusionary Zoning (IZ), will make conversions less attractive. Under the District’s new Inclusionary Zoning expansion, any mixed-use and residential project that is up-zoning through a map amendment to residential, must set aside 10-20 percent of its residential space for the affordable IZ units (IZ plus), and the Office of Planning has introduced amendments that would expand the regular IZ program to previously exempt zones (IZ XL), including non-residential to residential conversions.

The most important thing the D.C. government can do to pave the way to conversions is to articulate its policy goals.

Many of the factors that will determine whether a conversion will happen or not is outside of District’s control. But the city can help by clarifying the policy goal it wants to achieve through conversions: is it to increase housing units? It is to create a more mixed-use environment in parts of the city where that are made up of office buildings? Is it to revitalize parts of the city that have old buildings or little street level activity? Is it to create affordable housing? These goals can sometimes work against each other.

The city should balance its goals of increasing subsidized housing against the need to grow overall housing stock.

Affordability covenants could break conversion proformas and might require subsidies. The question, then becomes, what is the right mechanism for the city to elicit the most number of subsidized units?

As shown, there are too many building-specific factors that could make or break a conversion. So, rather than setting broad policy, we recommend the allocate a certain amount from the Housing Production Trust Fund for conversions, and then hold a “conversion competition” inviting developers and owners to submit their proposals to convert, including affordability covenants they propose to meet, and the requisite subsidies they would need to get there. The subsidies then can be directed to projects that promise the greatest value.

Appendix 1 – Residential Conversions in the District since 2002

Appendix 2 – Change in office building valuations

Appendix 3 – Vacancy rate and rent growth in commercial office buildings

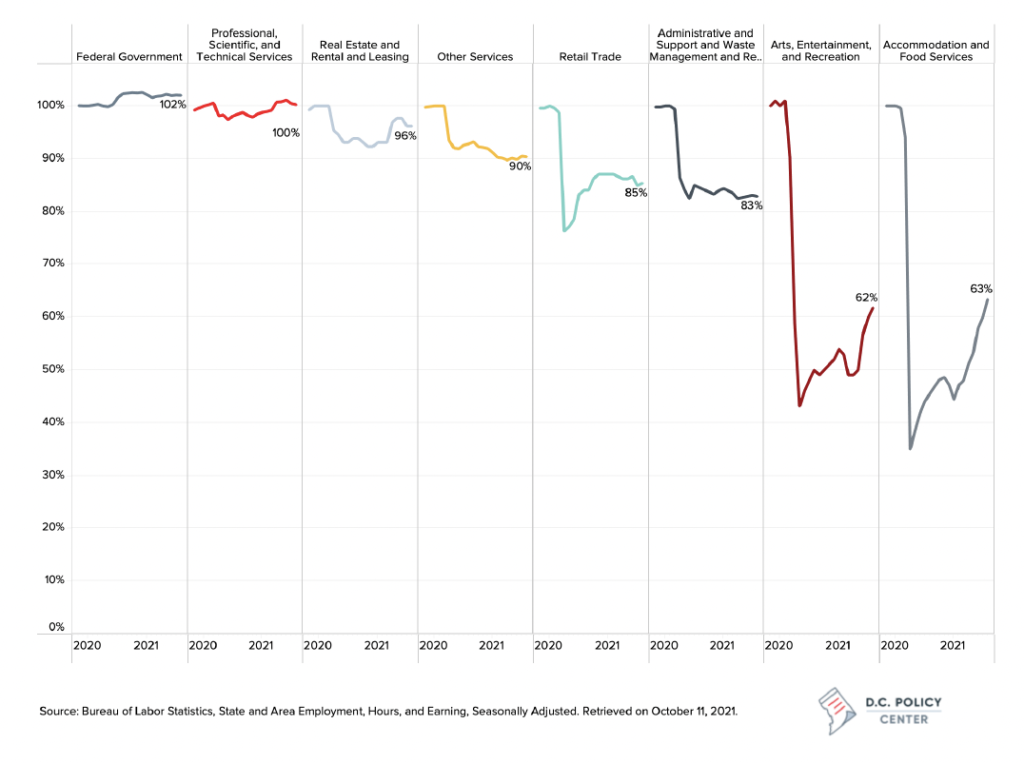

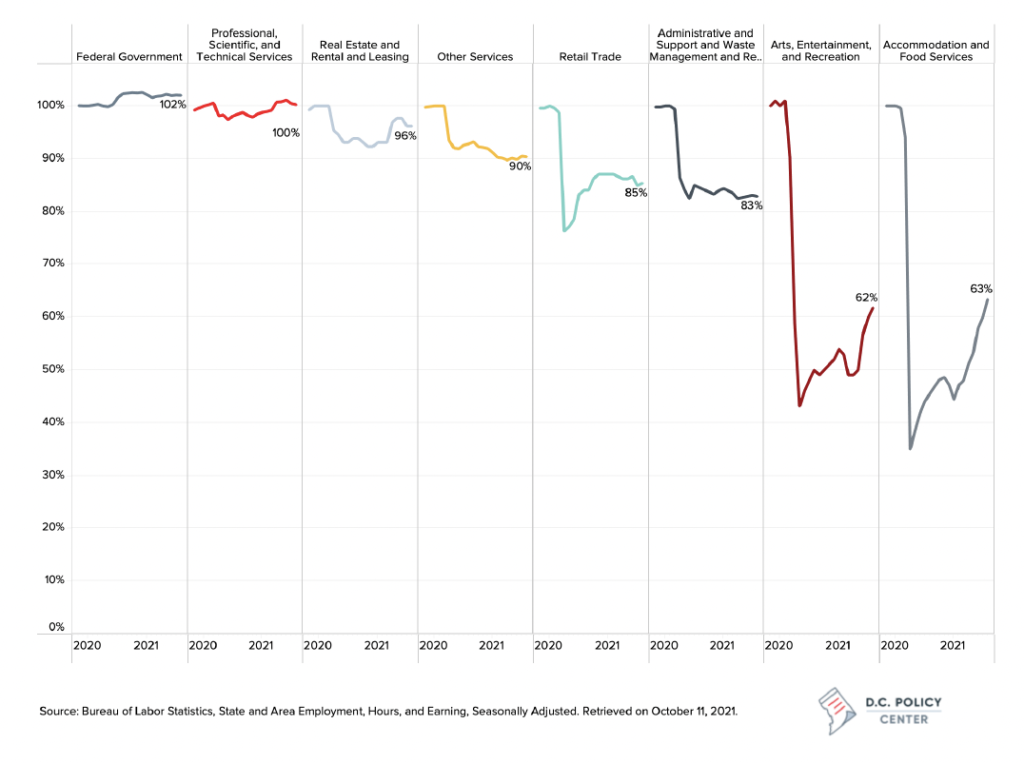

Appendix 4 – Employment relative to January 2020, selected sectors