I spent much of the 1960s as a full-time civil rights worker. From shortly after the great March on Washington of August 1963 through the Poor People’s Campaign of May-June 1968, I worked for the Washington Urban League, rising to assistant director under Sterling Tucker, our executive director.

I remember well the meetings of the local Urban League’s board of directors (for which I prepared monthly program progress reports). The two dozen members basically divided into two groups.

Washington Urban League – 1960s

One group was white businessmen (and one white business woman, a vice president of Woodward & Lothrup, DC’s largest department store). They were owners of large businesses like Morton’s department stores and Hechinger’s hardware store chain. Or they were senior executives in the electric, gas, and telephone companies, local banks, and savings and loan associations.

The other group was composed of black professionals (more committed to social justice than sociologist E. Franklin Frazier’s classic characterization of the Black Bourgeoisie). They included pastors, lawyers, accountants, school principals, a Howard University professor, a highly respected doctor who taught at Howard University’s medical school, and the owner/director of a leading funeral home.

The grande dame of the board was a graduate of DC’s once-famed Dunbar High School, who complained wistfully to me about how desegregation (just nine years earlier) had converted Dunbar from the segregated black community’s prestigious, selective, city-wide college preparatory high school into a high school that could accept students only from the poorest neighborhoods where it was located.

The unifying thread for all African American board members was that they were serving a still-largely black community. Though some had migrated to the Gold Coast along upper 16th Street, NW, most still lived in traditional African American neighborhoods like Le Droit Park.

Northern Virginia Urban League – ca. 1993

Twenty-five years later I returned to DC after two decades in Albuquerque. The city was transformed in many ways. As my former Urban League colleague John Jacob reflected with a grin “By the mid-1970s, you suddenly looked up and the guys that had been out demonstrating in the streets were running the government” (including, I might add, my former boss, Sterling Tucker, who was chairman of the first D.C. Council).

Jake invited me to attend the annual dinner of the Urban League of Northern Virginia (which Jake and I had helped to found as the Alexandria branch of the Washington Urban League). As then-head of the National Urban League, Jake was keynote speaker. As I cross-referenced the board members seated at the head table with their affiliations listed in the dinner program, I realized that the economic base of the African American members had changed over the 25 years.

The pastors still led African American congregations (for even today 11 a.m. on Sunday remains the most segregated hour in American society). The African American lawyers, however, were now partners in major mainstream law firms. The African American CPAs worked in the Big Eight accounting firms. The African American businessmen and businesswomen were executives in major corporations. The educators led relatively integrated public schools.[1]

Shortly thereafter, during a consulting assignment for Sterling Tucker Associates, I was crunching 1990 census numbers for the Washington DC-MD-VA metro area. Within the metro area I looked for census tracts that had both an African American majority and a median household income higher than the metro-wide median household income – in effect, where the Black Bourgeoisie now lived. I was startled to find that of 22 such census tracts only four were located within the District of Columbia – all along the Gold Coast. The other 18 were located in Prince George’s County. Clearly the Black middle class had suburbanized.

It also confirmed a sense that I had developed in my first year back living in the District. Though the local African American community had achieved many advances during the two decades that I had been away in Albuquerque, yet to be poor and Black and living in certain DC neighborhoods was to be more isolated than ever, especially east of the Anacostia River.

I have written that in America economic segregation is replacing racial segregation in large U.S. metro areas. As I explained in that piece, Dr. John Logan’s project at Brown University is the source of my economic polarization index.[2] His data also break it down by major racial group so we can trace trends in economic polarization within each racial group.

Black Poor and Black Bourgeoisie – The Widening Gap

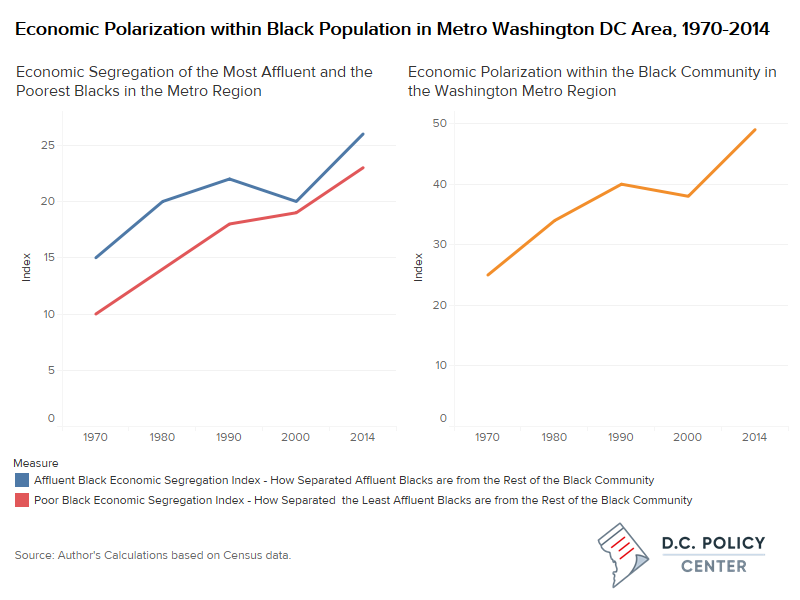

The charts below show economic segregation trends within our metro area’s Black community over the past 45 years. Tabulating income data for 1969, the 1970 census roughly corresponds to the end of my career with the Washington Urban League.

The “Affluent Black Economic Segregation Index” is a common dissimilarity index most often used by demographers. In this case it measures the degree to which the wealthiest 10 percent of the metro area’s Black residents live separated from the remaining 90 percent of the Black population.

Similarly, the “Poor Black Segregation Index” measures the degree to which the poorest 10 percent live separated from the remaining 90 percent. This group, in 1970, captured the poorest of the poor as in that year 18.4 percent of the black population fell below the poverty line so the poorest 10 percent covers barely half of them.

I have combined these two segregation indices to produce a Black polarization index. Decade by decade, the most affluent 10 percent were somewhat more set apart than were the poorest 10 percent. However, between 1970 and 2014 metro Washington’s Black polarization index almost doubled from 25 to 49.

Hence, my earlier observation (ca. 1993) that “to be poor and Black and living in certain DC neighborhoods was to be more isolated than ever” is borne out by the census data.

Putting Metro Washington in a National Context

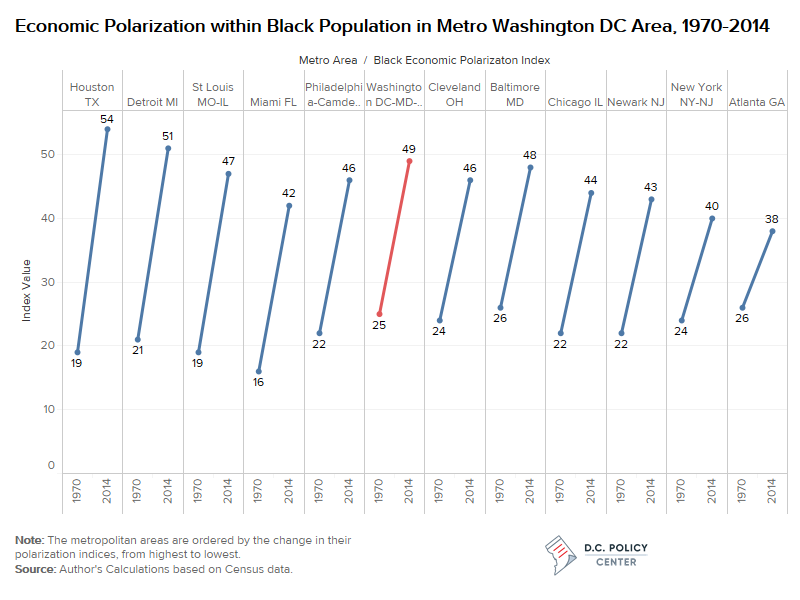

Let’s match up metro Washington with comparable areas. These dozen metro areas are all large (over 2,000,000) and have substantial Black populations.[3]

First, economic polarization within the Black community increased substantially in each of the 12 metro areas. By 2014, metro Washington had the third highest index of Black economic polarization (49) behind metro Houston (54) and metro Detroit (51). Metro Atlanta had the lowest index (38).

Second, the increases in economic polarization within the Black community were substantial everywhere with metro Atlanta again showing the least increase (12 points, from 26 to 38) and metro Houston the greatest increase (35 points, or 19 to 64). Metro Washington’s increase (24 points, or 25 to 49) actually tracked the group’s overall average increase.

Third, intuitively, one might think that greater Black-White integration as a whole would be the flip side of greater economic polarization within the Black community. However, there is no statistically significant correlation between these two metro-wide measures – the Black-White segregation index (the dependent variable) and the Black economic polarization index (the independent variable) – for these 12 major metro areas. Data are too global and affected by multiple variables and the sample size (12) is too small.

However, expanding the sample size to 30 large metro areas (all at least 1 million in population but with significantly lesser percentages of Black population than the original 12), a slight statistically significant correlation does emerge.[4] In general, the greater the increase in economic polarization within the Black community, the greater the overall reduction in Black/White segregation over the four decades.

A finer grained analysis, analyzing trends at the census tract level, will help illustrate the phenomenon for the Washington DC-MD-VA-WV metro area. That will be focus of “The Great Sort: Part II.”

David Rusk is a Senior Fellow at the D.C. Policy Center. Rusk is a former federal Labor Department official, New Mexico legislator, and mayor of Albuquerque, the USA’s 32nd largest city. He is also the author of Cities without Suburbs. Now a consultant on urban policy, Rusk has worked in over 130 US communities in 35 states. Abroad, Rusk has lectured on urban problems in Canada, England, Germany, South Africa, and The Netherlands.

Notes

[1] Fifteen years later I found that the principal of my old Charles Barrett Elementary School in Alexandria was now an African American woman; during my years at Charles Barrett in the late 1940s and early 1950s, my rigidly segregated school had no black pupils, no Jewish pupils, and I could not recall any Latino or Asian classmates. During a tour of my old school in April 2007 I found that the classrooms were a kaleidoscope of children of different origins. Twenty percent were Black (about two-thirds native-born African Americans, the remainder recent African and West Indian immigrants). Another 16 percent were Hispanic (with the largest group from El Salvador). Over five percent were Asian. Just 59 percent were White, including a number of children of recent Eastern European immigrants. (Almost 28 percent of Alexandria City Public Schools’ 10,334 students are enrolled in English as a Second Language classes; 80 different languages are spoken in their homes.) Don’t talk to me about “the Good Old Days.”

[2] American Communities Project available at https://s4.ad.brown.edu/Projects/diversity/IncSegsorting/Default.aspx

[3] In Census 2010, Metro Washington’s Black population was 25.2%. These metro areas range from Houston (16.8%) to Atlanta (31.9%).

[4] With an “n” = 30, the r-square is 0.18 with a t-value of -2.49 – a modest explanatory value.