Twenty-five years after the Revitalization Act fundamentally changed D.C.’s criminal justice system, few people fully understand that system’s scope and operation. Moreover, little analysis has been done on how the system operates as a whole and how it serves the District’s residents. The Revitalization Act shifted administration of D.C.’s criminal justice system mainly to the federal government. This makes D.C.’s system uniquely complicated, and has far-reaching impacts on D.C. residents.

What does the history of D.C.’s criminal justice system look like, and what changes were enacted under the Revitalization Act? This introduction to the District’s criminal justice system outlines its current structure, analyzes Revitalization Act changes have impacted justice system operations, and evaluates outcomes for D.C. residents.

About this series

This report is the foundation of the D.C. Policy Center’s Criminal Justice Week 2023, which explores various aspects of the District’s criminal justice system. Other publications in this series include:

- How D.C.’s criminal justice system has been shaped by the Revitalization Act

- Processing through D.C.’s criminal justice system: Agencies, roles, and jurisdiction

- A look at who is in D.C.’s criminal justice system

- How much would it cost to build and maintain a new D.C. prison?

- Map of the week: Where are D.C. Code offenders housed today?

Excerpted here is the introductory chapter of the report. Access this report in its original, print-friendly PDF format here.

Introduction

The District’s criminal justice system is complex and involves an overlapping system of agencies and organizations that are a mix of federally funded and under federal jurisdiction, federally funded and independently operated, locally funded and under local jurisdiction; and locally funded and independently operated. This unique configuration of entities with disparate leadership—which makes cooperation challenging, and systems change complicated—is the direct result of the federal Revitalization Act of 1997.

Congress enacted the Revitalization Act to put the District of Columbia on a viable fiscal path. In the mid 1990’s, the District of Columbia government had reached an untenable financial situation. In the wake of a recession,1 declining population, and a weakening tax base, coupled with poor financial management, the city could no longer pay for its expenses. By 1995, the District’s operating deficit had reached $722 million (18 percent of its projected spending that year),2 but with its bond ratings dropped to “junk” levels, the city was unable to borrow to manage cash flow, meet spending needs, or invest in infrastructure.3

With the city repeatedly spending more than its approved budget, in 1995 the Congress passed legislation to create a Financial Control Board that would oversee the finances of the District.4 However, the city’s challenges were too big to be solved purely through financial management. Challenges that faced the District included a crumbling infrastructure, a high Medicaid cost burden,5 a $5 billion unfunded pension liability it took over from the federal government with Home Rule in 1974,6 and high spending needs driven by the District’s obligation to provide both state and local level functions with a restricted revenue capacity. Infrastructure needs were particularly dire across the District’s criminal justice system: for example, overcrowding7 and decrepit living conditions at the Lorton Correctional Complex resulted in several large-scale riots throughout the 1980s and 1990s, including one incident in which 14 buildings were set on fire.8

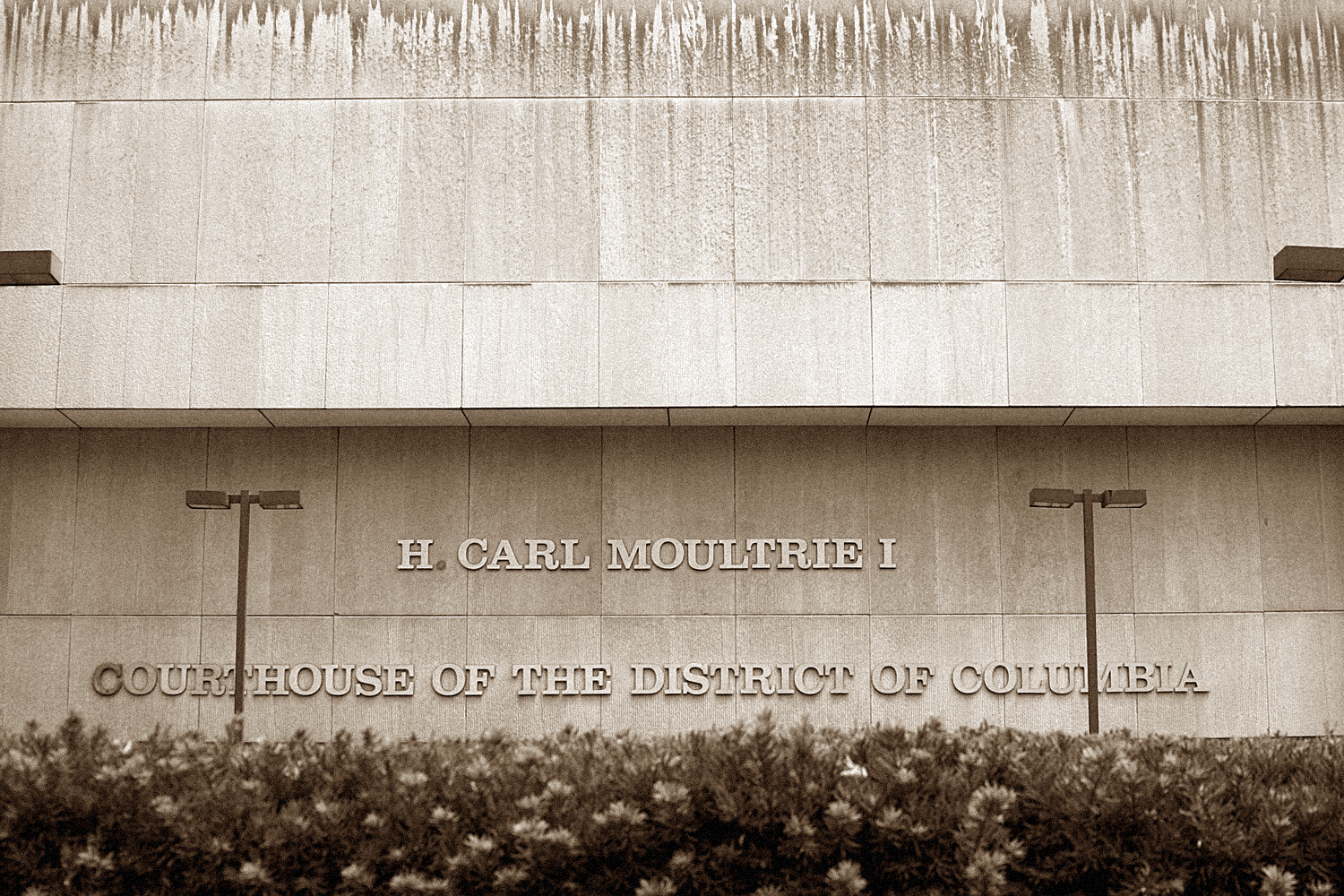

Additionally, the city’s court buildings were in dire need of infrastructure investments for which the city had no means to pay. Providing needed financial relief to the District, the National Capital Revitalization and Self-Government Improvement Act of 1997 (the Revitalization Act) was enacted on August 5, 1997. The Revitalization Act included numerous federal supports and interventions to help D.C. gain its fiscal footing. First, the federal government agreed to overtake various financial and managerial obligations including the D.C. courts, the prison system and the custody of incarcerated persons, and all pension liability accumulated through 1997. The local Medicaid match requirement was reduced from 50 percent to 25 percent (although this was done in an annual appropriations bill, not in the Revitalization Act), and the federal government provided the District with the authority to borrow from the Federal Treasury to finance $400 to $500 million of its debt because the city’s bond ratings had foreclosed any opportunity to borrow from markets. In return, the city gave up an annual federal payment of $660 million.

With federal takeover of many of the functions, The Revitalization Act fundamentally changed the District’s criminal justice system. These changes included:

- Closing the District’s Lorton Correctional Complex and transferring custody of D.C. Code offenders with sentences over a year to the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP);

- Abolishing the D.C. Board of Parole and transferring decision-making authority over parole matters to the U.S. Parole Commission (USPC);

- Reassigning pretrial and post-conviction community supervision responsibilities from the courts to the Pretrial Services Agency (PSA) and the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA);

- Taking over the financial responsibility for the operations of the District of Columbia Court System, including the D.C. Superior Court and the D.C. Court of Appeals;

- Classifying the District’s Public Defender Service (PDS) as a federally funded entity; and

- Establishing the Truth in Sentencing Commission (which later became the District of Columbia Sentencing Commission).

Now, 25 years since the enactment of the Revitalization Act, few people fully understand the scope and operations of the District’s current criminal justice system, and little analysis has been done on how the system operates as a whole and how it serves the District’s residents. This report chronicles the history of D.C.’s criminal justice system, describes what changes were enacted under the Revitalization Act, outlines the current structure of the District’s criminal justice system, analyzes how these changes have impacted justice system operations, and evaluates outcomes for D.C. residents.

In conducting this analysis, the D.C. Policy Center worked with the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council (CJCC) to meet with ten local and federal agencies to gather historical perspective, discuss the current status of each agency, and acquire data, when possible. The information presented in this report relies on multiple publicly available sources including annual reports of federal and local government entities, public databases, budget requests, congressional testimony, and case law. The D.C. Policy Center also conducted desk research of studies that provide historical and system perspectives.

The main takeaway from the research conducted for this report is that while some parts of the criminal justice system are extremely well-resourced with federal funding that provides significant fiscal benefits to the District of Columbia, many aspects of the system remain opaque to outsiders and difficult to assess. The D.C. Policy Center was able to interview representatives from all major entities that are part of the system, but publicly available information was insufficient to develop a clear picture of institutional practices and decision-making processes. To build this picture, the report had to rely on case law, testimony, and other secondary sources such as scholarly articles, reports, and third-party analyses, which may have potentially introduced anecdotes and interpretations from the authors of the said studies that could not be verified by data, into the analyses.

Further, it is difficult to provide an assessment of what the District’s criminal justice system would have looked like if all its components were under local control. We simply do not know the counterfactual path of fiscal and institutional decisions. Similarly, it is difficult to compare the District’s criminal justice system to systems in other jurisdictions on matters including funding, operations, and demographics of the District’s incarcerated population. In terms of individual experience with the criminal justice system, it may be more appropriate to compare D.C. to other cities given the District’s urban nature. But from a systems and funding perspective, it is more appropriate to compare the District to states and localities combined, since the District functions as both a state and local government and has both the revenue raising capacity and expenditure obligations of both a state and a local government.

The federalization of D.C.’s criminal justice system makes comparison even more difficult, since it means that that federal funding of many of District’s agencies do not appear on the District’s budget books, and many agencies operate under federal guidelines or in federal systems.

Keep reading via the full PDF »

Editor’s note: In August 2023, this report was updated with a correction to Figure 1.

Acknowledgements

This report has been commissioned by the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council (CJCC) under contract number CW93501. The authors thank CJCC for their valuable comments and suggestions, and for the facilitation of meetings and interviews with various local and federal government agencies who are a part of the District’s criminal justice system. Their review does not endorse this report, and all errors are the responsibility of the D.C. Policy Center authors. The views expressed in this report are those of D.C. Policy Center researchers and experts and should not be attributed to members of the D.C. Policy Center’s Board of Directors or its funders.

Endnotes

- The 1990-91 recession was one of the shortest and mildest recessions in the U.S. history. The recession lasted for 8 months from June 1990 to March 1991, but employment did not recover until 1992.

- General Accounting Office (1995), “District of Columbia Financial Crises, Statement of John W. Hill, Jr. Before the Subcommittee on the District of Columbia, Committee on Appropriations, and the Subcommittee on the District of Columbia, Committee on Government Reform and Oversight, House of Representatives.”

- Bouker, J. (2008). Appendix 1 – The D.C. Revitalization Act: History, Provisions and Promises.

- District of Columbia Financial Responsibility and Management Assistance Act of 1995, Pub. L. 104-8 (1995).

- The high spending in Medicaid was due to two factors. First, while the District’s median income was higher than the fifty states, concentrated poverty meant a large share of residents were eligible for Medicaid. Second, because of the high median income, the District had to match 50 percent of all Medicaid expenditures—the highest match rate possible under the federal formula.

- Prior to Home Rule in 1974, all D.C. government employees were technically federal government employees eligible for pension. When D.C. received Home Rule, these employees were reclassified as D.C. government employees, and city became liable for their pension benefits, which was estimated to be $2 billion and was entirely accumulated by the federal government. Over the next twenty years, this unfunded pension liability grew to $5 billion.

- By 1995, Lorton had around 7,300 inmates, or 44 percent more than intended for that facility.

- “Prison Set Ablaze During Riot.” (1986). Chicago Tribune.