The headlines from the proposed Fiscal Year 2020 Budget for the District of Columbia include $127.9 million in net new revenue, largely—but not entirely—raised from commercial real property.

The administration rationalized these new taxes as asking the real estate sector to share the “upside,” and pay for investments in housing affordability in the form of significant increases in spending to build low- and middle-income housing. Just to be clear, these expenditures are one-time, meaning while they are in the proposed Fiscal Year 2020 budget, they are not included in the expenditure projections for following years.

What happens to this newly raised revenue in Fiscal Year 2021, when one-time housing programs that collectively add up to about $91 million come to an end? Will the city have in hand another round of $91 million to invest in new programs? Add $91 million to its savings in following years? Reduce debt service by reducing borrowing? Do we see an increase in the projected operating margin in the financial plan in Fiscal Year 2021 by $91 million? The answer, on all counts, is an unqualified “no.” In fact, financial projections show the city will have to cut its expenditures by $60 million.

This confusing picture can be traced back to the misleading rhetoric around how the city is paying for one-time expenditures, be it housing, one full year of free Circulator service, more money for the Kids Ride Free program, funds for legal services for immigrants, or relief funds for ratepayers facing ever-increasing impervious surface charges. Not with the “upside” tax as the administration would have you believe. Rather, the city would be paying for them with its savings from past years.

The proposed Fiscal Year 2020 budget dips into the city’s fund balance to the tune of $391 million, paying for not only all of the one-time increases ($189 million in total) but also some of the recurring expenditures ($202 million). When this money largely disappears in Fiscal Year 2021, the revenue growth, even with the new taxes, is no longer sufficient to pay for the expenditure growth. The projected expenditures in Fiscal Year 2021 are not declining because costs or spending needs are somehow going to be lower. The projected expenditures in FY 2021 are shown to decline because they must.

Revenue increases in the proposed FY 2020 budget are not paying for new initiatives; rather, they are paying for a government that has been growing beyond what the existing revenue regime can support. This year’s new revenue initiatives are largely a catch-up—the second installment of the tax increases that began last year—for spending decisions of the past, especially decisions the Mayor and the Council made during last year’s budget cycle.

Fiscal Year 2021: The Year of Great Fiscal Reckoning

The Mayor’s proposed FY 2020 budget is growing faster than what the economic fundamentals can support. The proposed budget is built on an 8.2 percent increase in general funds, compared to a 4 percent growth in baseline revenues. The revenue forecast gets weaker in the out years because all metrics of consequence that shape the District’s tax base are growing much slower: personal incomes grew at 3.6 percent in the last quarter of 2018, wage and salary earnings in the city grew at 2.2 percent, and real property assessments mailed out in January show about 3 percent appreciation (commercial property assessments grew by 2.4 percent, and residential property by 4.2 percent). Resident employment grew by only 1.8 percent and the city added 6,764 new residents compared to the average growth of 11,315 net new residents each year in the previous four years.

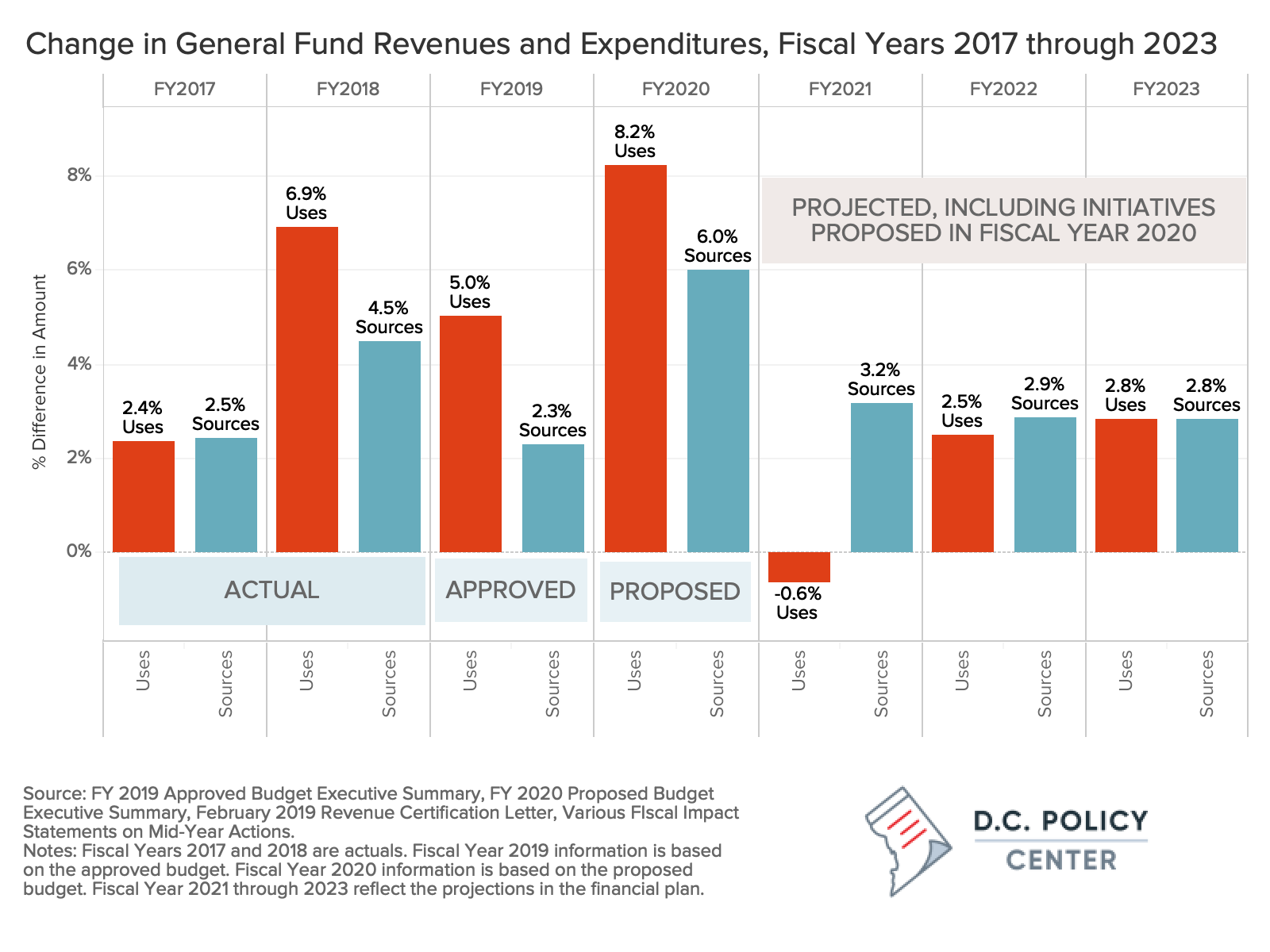

Fiscal Year 2020 is the third year in a row when the expenditure side of the budget (called “uses” in the chart below) is growing faster than the revenue side, including new and, sometimes unexpected, revenues and use of one-time money (collectively called “sources” below). In Fiscal Year 2018, the uses (based on actual expenditures) grew at nearly 7 percent, compared to 4.5 percent growth in sources. In Fiscal Year 2019, uses are growing at 5 percent based on the approved budget, sources at 2 percent when one includes the downward revisions the revenue estimators made in February. And finally, this year, even with new revenue initiatives and use of one-time money, the sources are growing at 6 percent compared to 8.2 percent in uses.

The projections for Fiscal Years 2021 through 2023 are especially important. This is not necessarily because they present a realistic picture of what the city’s future budgets will actually look like. Rather, they show us what needs to happen for the expenditure side to get back in line with the revenue growth, as required by law.

This picture tells us that a great reckoning awaits the District of Columbia in Fiscal Year 2021 to bring its fiscal house in order. That year, the current fiscal conditions will not afford any growth in expenditures—in fact, they demand a half percent cut ($60 million). And that reckoning can be by another piecemeal tax and expenditure policy, or it can happen through a thoughtful deliberation for a new fiscal vision that can support the District’s ambitions to become a growing, competitive, and socially and racially just city.

How did we get into this pickle?

If the city balanced its budget every year, meeting all of its legal obligations, why do we find ourselves looking at ever increasing taxes that still are not sufficient to pay for future expenditure growth? There are many reasons for it, but actions taken (and postponed) during the Fiscal Year 2019 budget process particularly stand out.

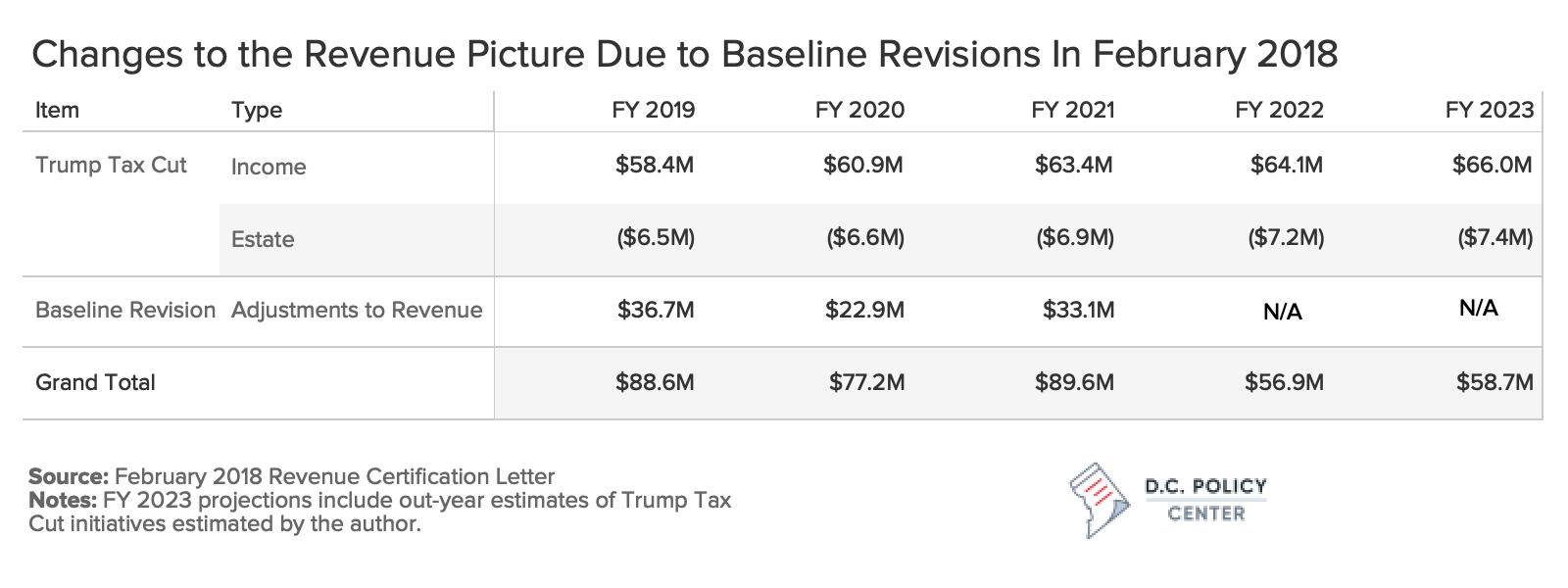

The District started its Fiscal Year 2019 budget season with some important news from the revenue estimators. The revenue estimators announced an unexpected $54 million windfall from the Federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act enacted by the Congress in December 2017. The federal tax changes redefined the income tax base, and in doing so, they did away with personal income tax changesthat were part of the Tax Revision Commission’s attempt to reduce personal income tax burdens and make them more equitable. The revenue estimators also increased baseline revenues for Fiscal Year 2019 and subsequent years to reflect better than expected tax collections. This meant, through all the changes, the city had $88.6 million more in hand than what previously had been expected.

The greatest pressure on the budget that year—beyond the usual advocacy demands and election year politics—was the need to fund Metro. A string of studies (here, here, and here) urged an increased commitment from the region to fund the capital needs for WMATA with “bondable” revenue—meaning dedication of reliable revenue sources that could be used to underwrite borrowing. And the desire for the Amazon HQ2 helped solidify the regional political will. To meet its commitment, the District had to restructure its Metro subsidy to dedicate $178.5 million in taxes for capital improvements for the transit system by Fiscal Year 2020. The money was not needed right away, but the agreement with our surrounding jurisdictions required immediate action to make sure money would be there when needed.

Given that the February 2018 Revenue Certification Letter had already dropped an unexpected $88.6 million into the District’s coffers, the additional resources required to meet the Metro obligation was about $90 million. And the Mayor and the Council got there through a set of bewildering revenue actions.

Fiscal Year 2019 Budget actions significantly changed the structure of the District’s commercial property taxes.

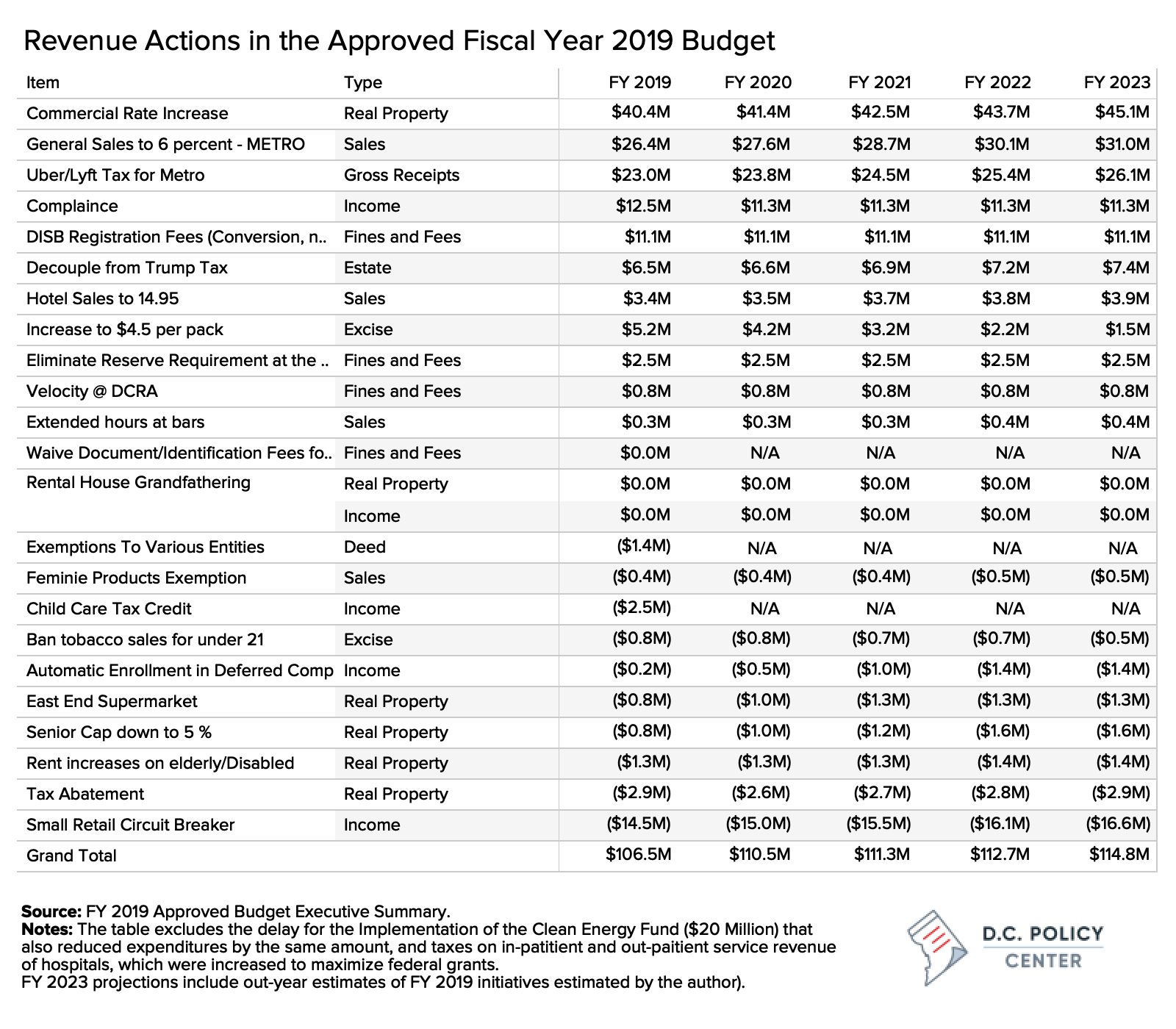

The most significant changes were made to the commercial property taxes. At that time of Fiscal Year 2019 budget preparation, the city was taxing the first $3 million in assessed value at 1.65 percent and any value above that at 1.85 percent. To fund the need for Metro (in addition to other initiatives reviewed below), the administration proposed to increase the upper tier to 1.87 percent, generating about $16.7 million.

When the Mayor’s budget reached the D.C. Council, the Council changed this tax structure entirely, removing the tiered property tax regime and replacing it with one where properties of different value would be taxed at different rates. Under the Council proposal, the city began to tax properties valued under $5 million at 1.65 percent, properties valued between $5 million and $10 million at 1.77 percent, and properties valued above $10 million at 1.89 percent. This change brought the total new revenue from commercial property tax increases to $40 million—a $23 million increase from what the Mayor had proposed.

But that was not all. When confronted by how property tax increases would affect commercial tenants—tenants who lease space in commercial buildings often bear the cost of property tax increases due to the structure of their leases—the Council decided to return $14 million to small retailer establishments (only) that might be overburdened by the tax increases. In addition, the city decided to abate the tax obligations of various entities including potential supermarkets in the East End ($4 million in revenue loss), cap the taxable assessments on residential property for certain seniors to 5 percent ($1 million in loss) and further reduce assessed values by limiting rent increases on seniors (and thereby limiting net operating incomes in apartment buildings subject to rent control) ($1 million). The net revenue impact of all these actions was $21 million.

Revenue side actions in the Fiscal Year 2019 Budget collectively raised $106.5 million; some for Metro, some for other programs.

Other notable actions in the Fiscal Year 2019 budget cycle include increasing the general sales tax to 6 percent (an additional $26 million), the tax on ride sharing companies from 1 percent to 6 percent (an additional $23 million) and the tax on hotels to 14.95 percent (an additional $3 million). While these changes were all made in the name of funding Metro, over half of this amount ended up paying for other things.

The city also found $13 million in new compliance initiatives, and a potential $11 million from registration fees collected by the Department of Insurance, Securities and Banking (DISB) in excess of what the agency needs and decoupled the city’s estate tax regime to take back the $6 million lost to the Trump tax cuts.

When all was said and done, the District had adopted ten new initiatives of consequence that collectively brought in $132 million and ten new initiatives that offered various tax breaks for $26 million, adding on net $106 million to revenue. Add on this the $88.6 million already in hand, the District had raised $195 million in recurring revenue, more than sufficient to meet the Metro obligations.

That year, the total budget increased by $436 million (operating budget by $454 million)—more than twice what the new revenue can pay for. The city filled in the gap that cannot be filled by baseline revenue growth and new taxes by taking out $206 million from its existing savings.

Metro funding raised through the Fiscal Year 2019 budget cycle was spent elsewhere that year.

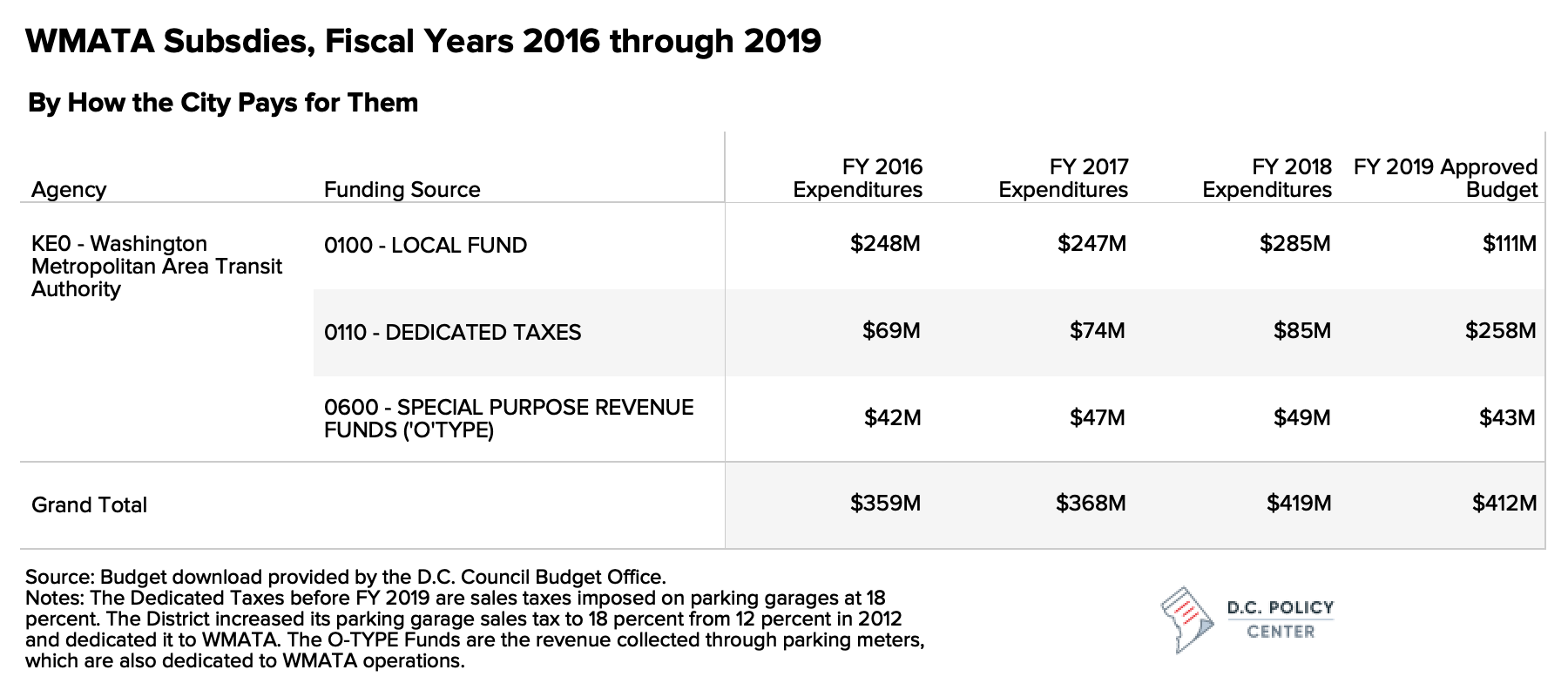

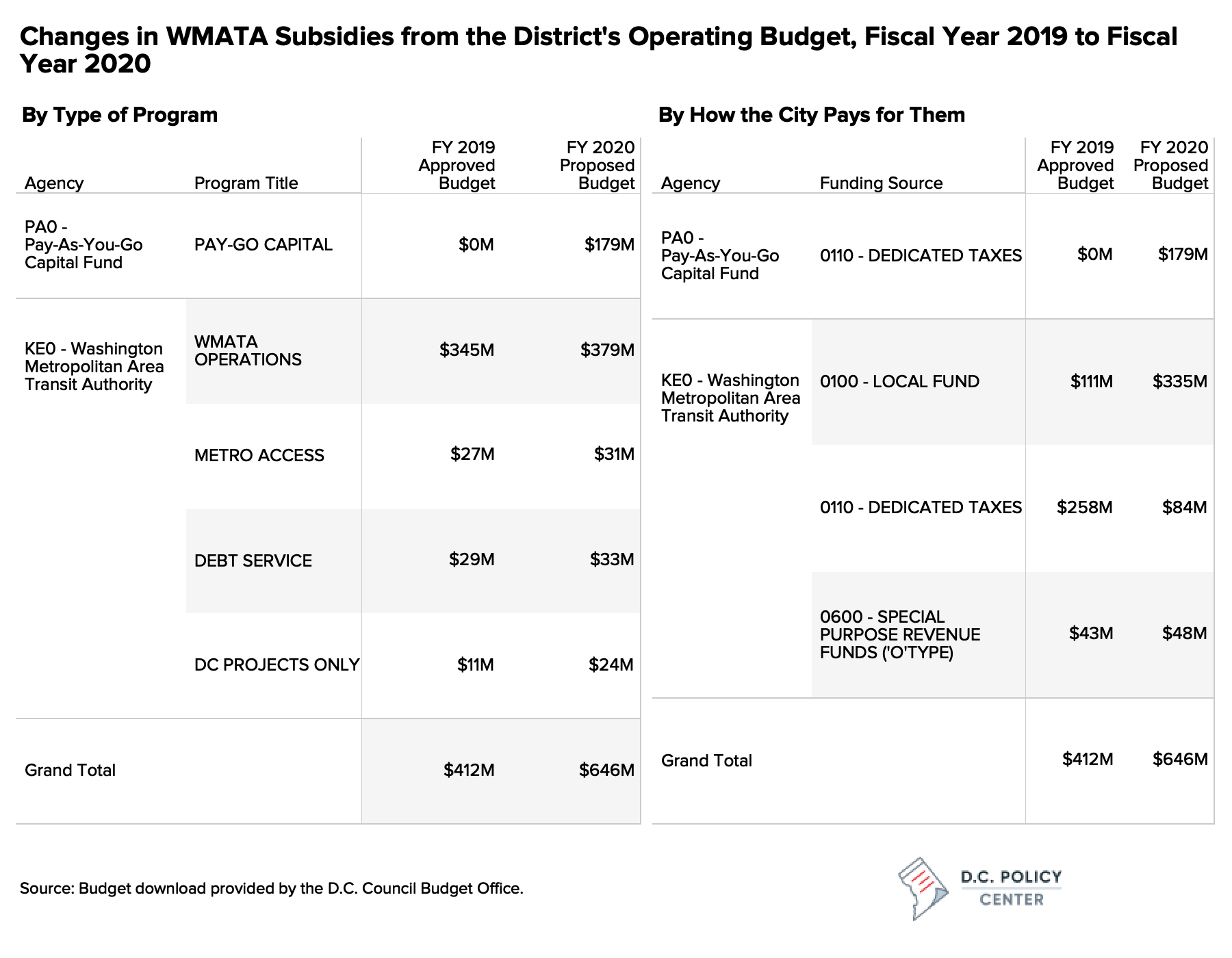

While the city had managed to dedicate the required $178.5 million to Metro, the total subsidy sent to WMATA in Fiscal Year 2019 was actually $7 million less that the subsidy in the previous year. In Fiscal Year 2018, the city had sent $418 million to WMATA from its operating budget, but of this amount only $18.5 million was supporting capital expenditures (debt service line in the table below). All other funds supported WMATA operations: a great bulk for subsidizing the operations of Metro Rail and Metro Buses ($335 million), some for District-only projects such as the Kids Ride Free program (a combined $42 million that year), and some for the Metro Access program that provides alternative transportation (vans with wheelchair access) for persons who are unable to use conventional trains and busses ($22 million).

With all the new revenue raised, the city had met its obligation to dedicate $178.5 million to WMATA’s capital needs. The laws adopted to implement the Fiscal Year 2019 budget included a provision that put this dedication on the District’s books. But note what happened to other local funds sent to the agency for operating subsidies that year: they went down from $285 million the year before to $110 million—down by $175 million, or about the same amount of money that was raised.

What happened to all this money? It was spent elsewhere. As budget geeks often say, “money is fungible,” so it is not particularly easy to track specific dollars to specific programs; all that matters is the bottom line. The Fiscal Year 2019 budget’s bottom line was that the money raised for Metro (and not really needed until 2020) was not set side for future use or put in the city’s savings account. It was spent on a series of one-time initiatives in the Fiscal Year 2019 budget including more money for the Housing Production Trust Fund, the one-time Child Tax Credit, among others.

The District’s share of WMATA contribution is now due. That is apparent in the jump in the subsidies to WMATA the District is sending from its operating budget. The total subsidy is up from $412 million to $646 million, and the $178.5 million the District committed in the Fiscal Year 2019 budget cycle is now showing up as “Pay-As-You-Go” capital, paid through dedicated taxes. There are other increases, too. The Mayor is proposing to send $34 million more to support WMATA operations and has added $13 million one-time money to the Kids Ride Free program. With other increases, the total jump in the WMATA budget is $234 million.

Importantly, the administration is not inclined to reduce spending. The general fund spending is up by $732 million in the Fiscal Year 2020 budget proposal. And within the general fund, one-time expenditures still exhaust a lot of resources. They are declining only by about $27 million in Fiscal Year 2020 (down from 206 million in Fiscal Year 2019 to $189 million).

In sum, the District raised money for a future obligation to the Metro last year, but spent the money on other things. This year, the obligation is due, and rather than cutting back on programs the District could not have afforded in the first place, the Mayor is proposing to raise taxes.

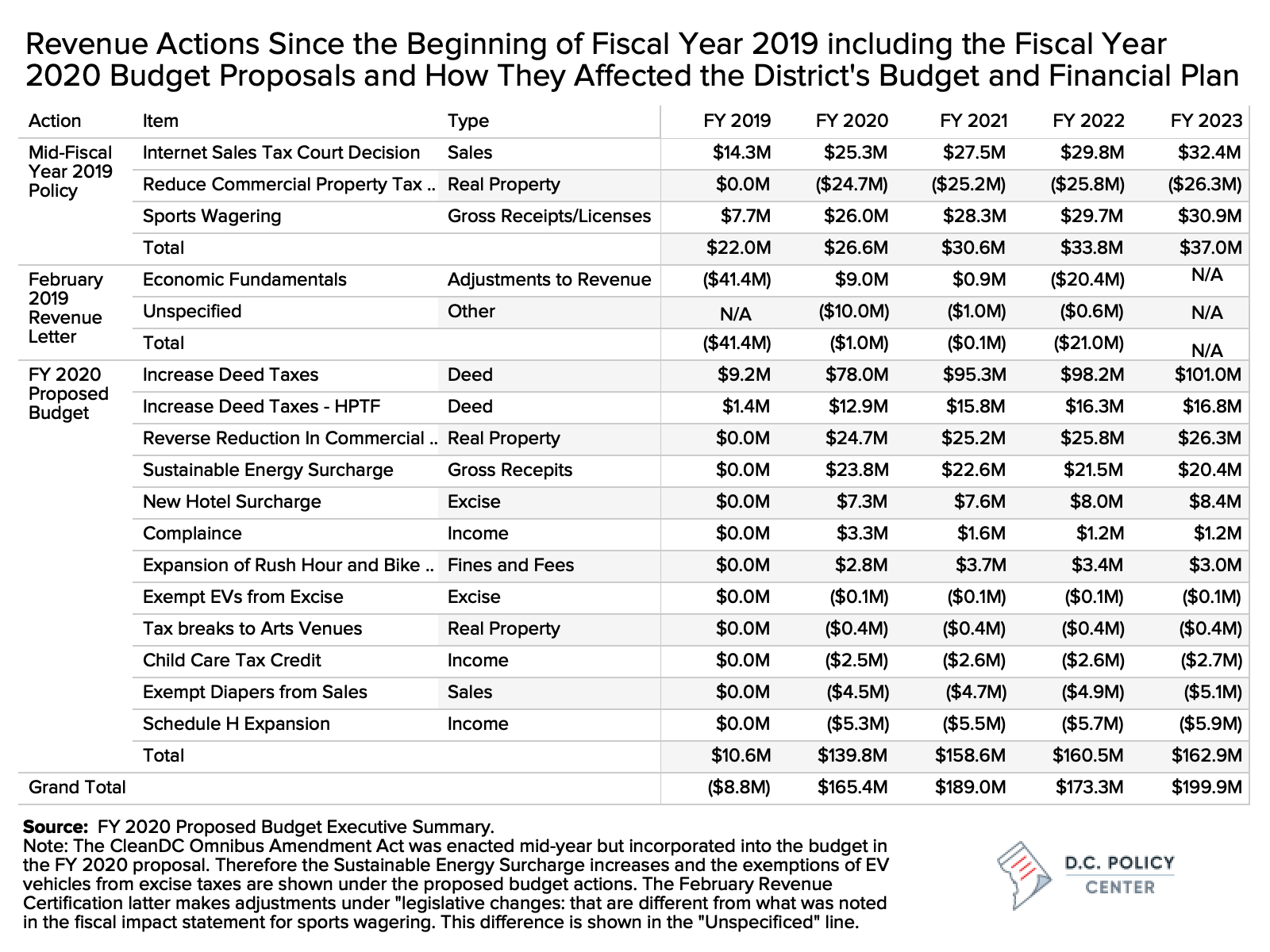

With all the changes since the adoption of the Fiscal Year 2019 budget, the District is adding $165 million more in revenues.

On June 21, 2018, the Supreme Court voted 5-4 to overturn Quill v. North Dakota, a 1992 ruling that stated that internet-based businesses were exempt from state sales taxes unless they had a physical presence in those states. This meant that the District could now collect sales taxes from all online vendors regardless of nexus, not just from those who had a presence in the city or voluntarily paid to D.C. sales taxes. Revenue estimators scored this as $25 million in new tax revenue beginning Fiscal Year 2020. In December, the Council voted (8 to 4, with one Councilmember abstaining) to use this money to reduce the commercial property tax rate for properties valued over $10 million down to 1.87 percent.

The city also adopted a sports wagering legislation that was estimated to generate a net new revenue of $26 million from the operations of the D.C. Lottery and taxes imposed on private operators.

In February, the revenue estimators did not deliver great news. They reduced the Fiscal Year 2019 revenue by $41.4 million reflecting the impact of the federal shutdown that paralyzed the District’s economy in December and January. Fiscal Year 2020 revenues were up by $9 million, but out years looked worse than what was previously expected.

Thus, the city started the Fiscal Year 2020 budget deliberations with about $26 million more in hand than the baseline revenue growth.

The Fiscal Year 2020 budget proposals now include six new revenue raisers that collectively add $152.6 million to recurring revenues and five new initiatives that collectively subtract $12.8 million, resulting in a net new revenue increase of $139.8 million through the following actions:

- A significant increase to deed transfer and recordation taxes (from a combined 2.9 percent to a combined 5 percent) to raise $90 million; of this, only $13 million is automatically dedicated to the Housing Production Trust Fund; the rest goes to the general fund to balance the budget.

- A reversal to the reduction in commercial property tax rates the Council had approved in December to raise $24 million. This is the fifth major policy initiative and the third legislative change to the commercial property tax rates in a single year.

- Full implementation of the CleanAir DC Omnibus Amendment Act of 2019 to add $23 million in new revenue. The entire revenue is all earmarked for new spending or tax expenditures approved by the Act.

- A new nightly 80¢ surcharge on hotel roomsto raise $7.2 million. This money will be used to improve E911 infrastructure, a need previously paid for by surcharges on land lines and cell lines but are no longer generating the necessary revenues.

- Compliance initiatives add $3 million, improvements to rush hour traffic control adds another $2.2 million (this last one is entirely spent on enforcement).

- The revenue reductions, in comparison, are modest, and include a $2.5 million child care tax credit which had been adopted only for one year in Fiscal Year 2019, but would now continue indefinitely, if the Council approves. There is also a $4.5 million tax expenditure that would exempt diapers from sales taxes and $5.3 million reduction to personal income taxes as a result of an expansion to the District’s circuit breaker program, which targets low-income home owners and renters.

When combined with mid-year actions, the Fiscal Year 2020 Budget Proposal operationalizes $165 million in new revenue. Not included in the table, but equally important, is the decision to use $391 million taken out of the District’s fund balance, to balance the budget.

What next?

The Council is now deliberating on the budget. And it is starting with a proposal that left many unhappy, both on the tax side and on the expenditure side. Chairman Mendelson’s response to the budget—which lamented both the tax increases and the lackluster spending—perfectly embodies the Council’s conundrum.

If past is prelude, the Council will add, and not subtract from spending. And it will likely add more complications to the tax code, looking for other last-minute revenue raisers. And through such actions, the Council could well make the District’s fiscal future even darker.

To be sure, it’s easy to dismiss this gap between revenues and expenditures as something that will be resolved through various outside forces. After all, the planned fund balance use for Fiscal Year 2020 is 4 percent of the general fund expenditures. You will be told that the actual amount the city draws from its fund balance will decline if revenues exceed expectations or actual spending is less than what is planned—both have happened, and happened frequently, in the past. And if good fortune misses the District this year, you will further be told, the Chief Financial Officer would force a balanced budget.

This last one gets me every time. The independent Chief Financial Officer will ensure—as he did in the past including through the worst recession years—that budgets are balanced. The Control Board will continue to work as a stick, yet will not come back. But is this the only framework through which we approach fiscal policy? That spending will be curtailed if need be by the independent Chief Financial Officer?

This handwaving delegates the tough decisions of which programs to cut and which to fund to the CFO, but it is not the CFO’s job to balance the Council’s competing promises and policy priorities. The CFO is not responsible for building fiscal policy that can push back against displacement, concentrated poverty, or racial inequities; his job description does not include building budgets that can support families, breathe life into new businesses, or fix housing. These responsibilities belong to the elected officials.

To be sure, the administration and the District’s legislators do put great thought into the city’s social ills and how to address them. District agencies and the Council employ many dedicated and hard working people who deeply think about these issues and develop solutions. But the budget picture tells us that the District’s fiscal regime needs a bit of luck every year to execute the current vision.

Building the will for a new fiscal vision

The political will to restructure fiscal policy to support the District’s ideals may not be here during this budget cycle. But this will cannot arise without preparation and commitment.

Building a fiscal vision requires much more thought than is possible during the District’s compressed, and politically charged annual budget process. And it requires thoughtful deliberation on both the revenue and the expenditure sides.

On the revenue side, the elected officials should consider the simplest, most efficient ways of raising revenue, specifically from where value has been capitalized most rapidly. This will require a major revision of the District’s real property tax regime—including its residential tax regime, which handsomely rewards home ownership without any consideration for income or wealth, and while doing so, amplifies racial inequities, contributes to concentrated poverty, and increases displacement as well as the exodus of the middle class (here, here, and here). A careful consideration of the District’s real property tax regime is especially important given that the last Tax Revision Commission did not make any recommendations for real property taxes, and the haphazard and inconsistent real property tax policies of recent years have moved the District away from sound tax policies.

On the expenditure side, the District should assess cost drivers that might be different from those of yesteryear. For example, the growth in the population of school-age children, combined with parents increasingly opting in for public schools suggest that education—including capital investment needs—will continue to be a cost driver. The growing enrollment projections (here and here) and the estimated needs in the recent Master Facilities Plan all leave out the decisions on how growing needs in public education can be fit into the current fiscal picture. Improving quality of life through better business climate, better transportation, higher investments in health and education in East of the River communities cannot be achieved by piecemeal policies, and must be a part of a vision with fiscal grounding.

The District succeeded to implement such visions in the past, through three different Tax Revision Commissions on the revenue side, and through various working groups—the first one here, and the latest of which was the Affordable Housing Preservation Strike Force—on the housing side. Convening a similar commission whose work can inform the city’s fiscal vision before the FY 2021 fiscal cliff is particularly timely and important.

The need for a “Great Fiscal Reckoning” can be dismissed, or preparation for it can be kicked down the road with piecemeal tax and expenditure policy that balances the budget. Or the reckoning can happen through thoughtful deliberation for a new fiscal vision that can support the District’s ambitions to become a growing, competitive, and socially and racially just city.

We advocate for the latter.

Data

The data underlying the chronological analysis has been gleaned from various budget books, fiscal impact statements, and revenue certification letters. For those interested, it can be downloaded here.

CORRECTION (11:20 AM): The FY 2019 Actions table has been updated with the correct version. The text except for the heading for that section remains the same.