This article is the seventh and final post in a series focusing on circumferential transit in the Washington, D.C. region. Read part one, part two, part three, part four, part five, and part six.

While extensions to the Purple Line and rail transit along the Beltway are popular ideas for improving transit within and across the D.C. region, they are certainly not the only options for improved suburb-to-suburb transit service in the metro area. Other possibilities for light rail exist, and there are many places where Bus Rapid Transit-type improvements could significantly improve transit service.

The obvious place to consider such routes is in Washington’s Maryland and Virginia suburbs. However, the District itself is also home to important crosstown bus lines that serve the same type of non-radial trips, and should be thought of as part of the region’s circumferential transit network. Many of these crosstown bus corridors could benefit from improved service and infrastructure. Let’s take a look.

Crosstown buses north of downtown D.C.

North of downtown D.C., Rock Creek forms a major barrier to east-west bus routes. East-west routes can only really cross the creek on Calvert Street, Porter Street / Klingle Road, and Military Road. Tilden Street and Blagden Avenue could potentially also serve as connections, but both are very indirect in connecting the two sides of the creek, and there is no bus service across them today.

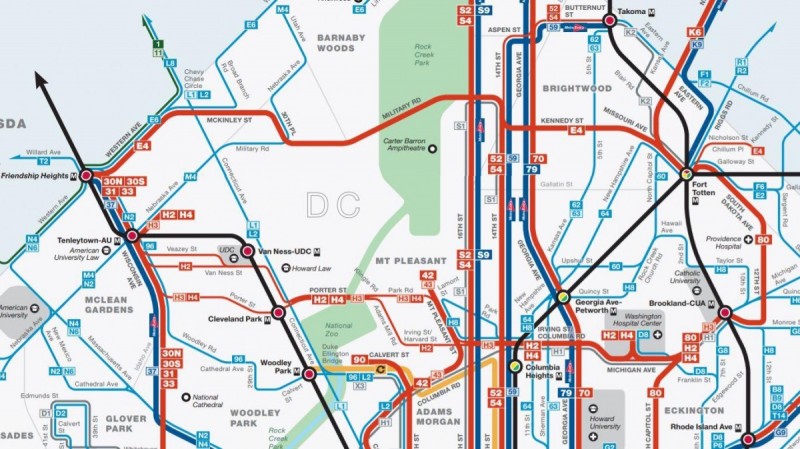

Each of the three major possible crossings north of downtown are used by important bus routes today: the E4 runs from Friendship Heights to Ft. Totten using the Military Road crossing; the H2/H4 connect Tenleytown and Cleveland Park with Columbia Heights, the Washington Hospital Center, and Brookland; and the McPherson Square/Woodley Park Circulator crosses the Calvert Street bridge. The latter is primarily a radial route that runs along 14th Street for most of its length.

This clipping from WMATA’s D.C. bus map shows the limited east-west connections north of downtown, and the 90 bus’s failure to cross Rock Creek. Image by WMATA.

While the 90 bus does not cross Rock Creek—it terminates at the eastern end of the Duke Ellington Bridge on Calvert Street—it provides an important circumferential service north and east of downtown. The 90 runs north-south on 8th Street SE/NE from the Anacostia Metro station to Florida Avenue NE, with a stop at the Eastern Market Metro station. It then runs east-west on Florida Avenue NE/NW and U St, with transfers to the NoMa and U Street Metro stations before continuing up 18th Street to Calvert St. This produces a nearly half-circle circumferential loop around downtown, connecting four Metro stations and every Metro line.

The fact that east-west routes are limited to only a handful of streets makes it difficult to establish a regular bus grid in the northern portion of the District, but it also adds greatly to the importance of the handful of routes that are possible. Each of them needs to knit together Metro stations on the Green line and both branches of the Red line, while also serving the important destinations that aren’t near Metro stations.

Improving service on the E4 and H2/H4

The E4, depending on traffic, can be five minutes faster than riding the Red Line from Fort Totten to Friendship Heights. It also provides a connection to Metro for large portions of northwest D.C. on both sides of Rock Creek that lack nearby Metro stations.

The H2/H4 takes roughly the same time as the Red Line to carry passengers between its termini, but it provides an important connection between both branches of the Red Line and the Green Line at Columbia Heights. It also connect a major destination—the Washington Hospital Center—which is not served by Metrorail, to both the Red and Green lines.

Both the E4 and H2/H4 pass through dense D.C. neighborhoods, and cross the highest-ridership bus lines in the region on Georgia Avenue and 16th Street. However, they run too infrequently to really work as connecting parts of a multi-line trip. The E4 runs only every 30 to 40 minutes on weekends and evenings, while the H2/H4 run every 20 to 30 minutes on the combined portions of their routes during those times.

Both the E4 and H2/H4 should have their off-peak frequencies increased to every 10 to 12 minutes, and WMATA should consider consolidating the separate portions of the H2/H4 into a single route for better reliability and higher frequency in the areas where the routes separate.

Increasing the speed of the buses will both reduce travel time for passengers and reduce operating expenses, which would help with the costs of increasing frequency on these routes. Options for doing so include consolidating close-together stops, adding signal priority for buses, and adding bus lanes where possible.

D.C.’s recent Crosstown Multimodal Study recommended several improvements along the H2/H4 line, including dedicated peak-period bus lanes between Columbia Heights and Brookland, transit signal priority at several intersections, and a straighter path through the hospital, where buses today take a long and circuitous path. The District should implement these recommendations, and conduct a similar study for the E4 route to determine whether bus lanes and signal priority could be used to speed buses between Fort Totten and Friendship Heights.

The 90/92 bus and the McPherson Square-Woodley Park Circulator

Although it doesn’t cross Rock Creek Park, the 90/92 bus line is the closest thing to an inner Purple Line as exists in today’s bus system. The 90 route forms a half-loop around the north and east sides of downtown D.C., starting at Rock Creek and Calvert Street, then running east and south along 18th Street, U Street, Florida Avenue, and 8th Street NE/SE, before crossing the Anacostia River and terminating at the Anacostia Metro station.

The 92 route is similar, but has its western terminus at the U Street Metro station. It also follows a different route south of the river and terminates at the Congress Heights station instead of the Anacostia station.

The 90/92 line has direct transfers to all six Metro lines (sometimes more than once), the D.C. Streetcar, and most of D.C.’s high-ridership radial bus lines. However, the 90’s failure to cross Rock Creek leaves a half-mile walk between its terminus at the Calvert Street bus loop and the Woodley Park/Zoo Metro station. The terminus for the 90 is located where it is because the tracks for its predecessor streetcar line ended in a loop on the east side of the bridge.

Calvert Street bus loop at the foot of Duke Ellington Bridge. Image by BeyondDC licensed under Creative Commons.

While ending the 90 route at the bus loop is operationally convenient, it is neither good for passengers nor necessary. The McPherson Square/Woodley Park Circulator provides every 10-minute service across the bridge, and terminates at the Woodley Park Metro station. A natural service improvement would be to extend the 90 across the bridge to the Woodley Park station, and perhaps further west to American University, bringing this “inner Purple Line” to near the District’s western border.

Like the H2/H4 and the E4, the 90/92 bus line would benefit from frequency improvements. At present, the portion of the line served by both routes has buses every ten minutes during weekday mid-day, but only every 15 minutes in evenings and weekends.

WMATA bus with mockup of a dedicated lane. Image created with Google Maps.

The headways on the shared part of the line are reasonable, though the 15-minute headways should be reduced to 10-12 minutes if possible. More concerning is the fact that the portion of the route served by only the 90 (from the U Street Metro station west) has twice-as-long headways, which makes transfering to it quite inconvenient: a particular problem with a circumferential route, many of whose riders will be transferring to a radial bus route or Metro line.

Speeding up bus service by consolidating bus stops, adding signal priority to more intersections, and potentially adding bus lanes where possible could also significantly help improve service on the 90/92, and would help reduce operating costs, perhaps offsetting the costs of increased frequencies.

Circumferential bus routes east of the Anacostia

As transit consultant and D.C. Policy Fellow Alon Levy discussed in depth last January, bus service east of the Anacostia is complicated by the irregular street grid, hilly terrain, and arterial streets that do not connect well to Metrorail.

Patchwork of bus services East of the Anacostia River. Image by WMATA.

Currently, a patchwork of different routes provide circumferential service between Wards 7 and 8 along Minnesota Avenue, Alabama Avenue, Southern Avenue, Eastern Avenue, and portions of other roads. In a perfect world, one would want to consolidate bus routes to form a frequent grid east of the Anacostia. However, in practice, the fact that many major arterials fail to connect to all of the Green, Orange, and Blue lines, along with hilly terrain that reduces the distance people are willing to walk to a bus stop, necessitates more routes.

As Levy notes, fare integration and free transfers between Metro and buses could help simplify the problem of providing affordable transit to residents east of the Anacostia. This would allow less money to be spent providing radial bus lines that essentially duplicate Metro routes. Adding bus lanes and signal priority to major corridors would, as with routes north of downtown, speed up service and reduce operating costs as well.

Freeing up that money might in turn allow more frequent and direct circumferential service, and more service on routes serving neighborhoods far from Metro. In particular, Minnesota Avenue could have frequent service running its length even off-peak.

Streetcars for circumferential service in D.C.?

D.C.’s major bus lines—radial and circumferential—are an important part of the District’s transportation network, and they need to be improved. In the short term, this means increasing frequency on major routes, and adding bus lanes and transit priority at intersections along these routes.

Rendering of the DC Streetcar on the K Street Transitway. Image by DDOT.

In the longer term, converting major bus routes to streetcars may make sense, since it would increase capacity and improve ride quality. However, if more streetcar lines are built, it is essential that, as with the potential extension of the H Street streetcar to Georgetown, they run in dedicated lanes and be designed to minimize delays due to car traffic. Streetcars do provide better transit service, but the first priority should be to ensure fast and frequent service, not mode choice.

It’s worth noting that in 2014 when D.C. was planning a 37-mile streetcar network, many of the lines would have served primarily crosstown and circumferential trips. Streetcars were proposed for corridors substantially similar to the H2/H4, the 90/92, and the V2/V4 on Minnesota Avenue, among others. While many of the most important potential streetcar lines are radial, there is a place for circumferential streetcar service in the District’s long-term transportation future.

This article is the final installment of a seven-part series focusing on circumferential transit in the Washington, D.C. region. The full series includes:

1. Why the Washington region needs better suburb-to-suburb transit

2. Our region needs better suburb-to-suburb transit, but a Metro loop isn’t the best option

3. The best way to build a Purple Line link between Bethesda and Tysons Corner

4. Why it makes sense to extend the Purple Line to Largo, but not National Harbor

5. Northern Virginia needs better suburb-to-suburb transit. Here’s where rapid bus service could help.

6. Here’s where rapid bus service could best connect Maryland’s suburbs

7. For circumferential transit in the District, try crosstown bus lanes

Feature image: WMATA bus with mockup of a dedicated lane, based on an image created with Google Maps. This article also appeared at Greater Greater Washington.

DW Rowlands is an adjunct chemistry professor and Prince George’s County native, currently living in College Park. More of their writing on transportation-related and other topics can be found on their website. They also write for Greater Greater Washington, where they are on the Elections Committee. In their spare time, they volunteer for Prince George’s Advocates for Community-Based Transit. However, the views expressed here are their own.